Magic square of squares

| Unsolved problem in {{{1}}}: {{{2}}} (more unsolved problems in {{{1}}})

|

The magic square of squares is an unsolved problem in mathematics which asks whether it is possible to construct a three-by-three magic square, the elements of which are all square numbers. The problem was first posed anonymously by Martin LaBar in 1984, before being included in Richard Guy's Unsolved problems in number theory (2nd edition) in 1994.[1]

The problem has been a popular choice for recreational mathematicians following two articles Martin Gardner published in Quantum Magazine on the problem, offering a prize of US$100 in 1996.[2][3] Other prizes have subsequently been offered for the first solution.[4]

Background

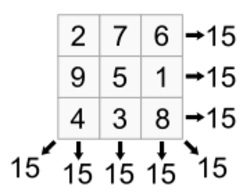

A magic square is a square array of integer numbers in which each row, column and diagonal sums to the same number.[5] The order of the square refers to the number of integers along each side.[6] A trivial magic square is a magic square which has at least one repeated element, and a semimagic square is a magic square in which the rows and columns, but not both diagonals sum to the same number.

Problem

The problem asks whether it is possible to construct a third-order magic square such that every element is itself a square number.[7] A square which solves the problem would thus be of the form

and satisfy the following equations[8]

Current research

It has been shown that the problem is equivalent to several other problems.[1]

- Do there exist three arithmetic progressions such that each has three terms, each has the same difference between terms as the other two, the terms are all perfect squares, and the middle terms of the three arithmetic progressions themselves form an arithmetic progression?

- Do there exist three rational right triangles with the same area, such that the squares of the hypotenuses are in arithmetic progression?

- Does there exist an elliptic curve, , where is a congruent number, with three rational points on the curve, , , , such that each point is "double" another rational point on the curve ("double" in the sense of the group structure for points on an elliptic curve), and , and are in arithmetic progression?

Brute force searches for solutions have been unsuccessful, and suggest that if a solution exists, it would consist of numbers greater than at least .[9]

Rice University professor of mathematics Anthony Várilly-Alvarado has expressed his doubt as to the existence of the magic square of squares.[8]

Notable attempts

There have been a number of attempts to construct a magic square of squares by recreational mathematicians.

Sallows' Square

Following Gardner's prize offer for anyone who could find a magic square of squares in 1996, Lee Sallows published his attempt in The Mathematical Intelligencer. His attempt is unique in that the all of the rows and columns, and one of the diagonals all sum to a square number.[10][8]

| 1272 | 462 | 582 | 1472 | |

| 22 | 1132 | 942 | 1472 | |

| 742 | 822 | 972 | 1472 | |

| 1472 | 1472 | 1472 | 1472 | 38307 |

Bremner Square

In 1999, Andrew Bremner published his attempt at the problem, and further research surrounding magic squares of squares.[11] Bremner's attempt differs from others in that not all elements of the square are square numbers, while all the rows, columns and diagonals sum to the same number.[8]

| 3732 | 2892 | 5652 | 541875 | |

| 360721 | 4252 | 232 | 541875 | |

| 2052 | 5272 | 222121 | 541875 | |

| 541875 | 541875 | 541875 | 541875 | 541875 |

Parker square

The Parker square[12] is an attempt by Matt Parker to solve the problem. His solution is a trivial, semimagic square of squares, as , and all appear twice, and the diagonal sums to 4107, instead of 3051.[13][9]

| 292 | 12 | 472 | 3051 | |

| 412 | 372 | 12 | 3051 | |

| 232 | 412 | 292 | 3051 | |

| 4107 | 3051 | 3051 | 3051 | 3051 |

Non third-order magic squares of squares

Magic squares of squares of orders greater than 3 have been known since as early as 1770, when Leonard Euler sent a letter to Joseph-Louis Lagrange detailing a fourth-order magic square.[14]

| 682 | 292 | 412 | 372 |

| 172 | 312 | 792 | 322 |

| 592 | 282 | 232 | 612 |

| 112 | 772 | 82 | 492 |

Multimagic squares are magic squares which remain magic after raising every element to some power. In 1890, Georges Pfeffermann published a solution to a problem he posed involving the construction of an eighth-order 2-multimagic square.[15]

| 56 | 34 | 8 | 57 | 18 | 47 | 9 | 31 | 260 | |

| 33 | 20 | 54 | 48 | 7 | 29 | 59 | 10 | 260 | |

| 26 | 43 | 13 | 23 | 64 | 38 | 4 | 49 | 260 | |

| 19 | 5 | 35 | 30 | 53 | 12 | 46 | 60 | 260 | |

| 15 | 25 | 63 | 2 | 41 | 24 | 50 | 40 | 260 | |

| 6 | 55 | 17 | 11 | 36 | 58 | 32 | 45 | 260 | |

| 61 | 16 | 42 | 52 | 27 | 1 | 39 | 22 | 260 | |

| 44 | 62 | 28 | 37 | 14 | 51 | 21 | 3 | 260 | |

| 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Robertson, John P. (1996-10-01). "Magic Squares of Squares". Mathematics Magazine 69 (4): 289–293. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1996.11996457. ISSN 0025-570X.

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (January 1996). "The magic of 3x3". Quantum 6 (3): 24–26. ISSN 1048-8820. https://static.nsta.org/pdfs/QuantumV6N3.pdf. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (March 1996). "The latest magic". Quantum 6 (4): 60. ISSN 1048-8820. https://static.nsta.org/pdfs/QuantumV6N4.pdf. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ↑ "Can You Solve a Puzzle Unsolved Since 1996?". Scientific American. October 2014. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-you-solve-a-puzzle-unsolved-since-1996/.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Steven (1994). The Words of Mathematics: An Etymological Dictionary of Mathematical Terms Used in English. MAA. p. 130. https://books.google.com/books?id=iuoZSkSOBQsC&pg=PA130.

- ↑ Wolfram MathWorld: Magic Square Weisstein, Eric W.

- ↑ LaBar, Martin (January 1984). "Problems". College Mathematics Journal 15: 68–74. doi:10.1080/00494925.1984.11972754. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00494925.1984.11972754. Retrieved 6 June 2025.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Várilly-Alvarado, Anthony; et al. (Numberphile). Magic Squares of Squares (are PROBABLY impossible) - Numberphile – via YouTube.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Boyer, Christian. "Latest research on the "3x3 magic square of squares" problem". http://www.multimagie.com/English/SquaresOfSquaresSearch.htm.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sallows, Lee (1997). "The Lost Theorem". The Mathematical Intelligencer. http://www.multimagie.com/Sallows.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bremner, Andrew (1999). "On squares of squares". Acta Arithmetica. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1b0d/bd7d764ece84e9b22b462927979c6e635676.pdf.

- ↑ Cain, Onno (2019). "Gaussian Integers, Rings, Finite Fields, and the Magic Square of Squares". arXiv:1908.03236 [math.RA].

Some 'near misses' have been found such as the Parker Square [2]

- ↑ Matt Parker; et al. (Numberphile) (April 18, 2016). The Parker Square - Numberphile. Retrieved June 6, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Boyer, Christian (12 November 2008). "Some Notes on the Magic Squares of Squares Problem". The Mathematical Intelligencer 27 (2): 52–64. doi:10.1007/BF02985794.

- ↑ Boyer, Christian. "Bimagic squares". http://www.multimagie.com/English/Bimagic.htm.

- ↑ Boyer, Christian. "Solution of the first bimagic square, 8th-order, of Pfeffermann". http://www.multimagie.com/English/Pfeffermann8.htm.

|