Maximal independent set

In graph theory, a maximal independent set (MIS) or maximal stable set is an independent set that is not a subset of any other independent set. In other words, there is no vertex outside the independent set that may join it because it is maximal with respect to the independent set property.

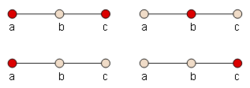

For example, in the graph P3, a path with three vertices a, b, and c, and two edges ab and bc, the sets {b} and {a, c} are both maximal independent. The set {a} is independent, but is not maximal independent, because it is a subset of the larger independent set {a, c}. In this same graph, the maximal cliques are the sets {a, b} and {b, c}.

A MIS is also a dominating set in the graph, and every dominating set that is independent must be maximal independent, so MISs are also called independent dominating sets.

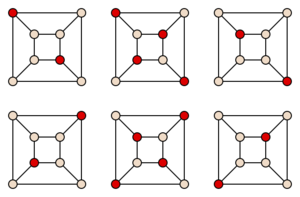

A graph may have many MISs of widely varying sizes;[lower-alpha 1] the largest, or possibly several equally large, MISs of a graph is called a maximum independent set. The graphs in which all maximal independent sets have the same size are called well-covered graphs.

The phrase "maximal independent set" is also used to describe maximal subsets of independent elements in mathematical structures other than graphs, and in particular in vector spaces and matroids.

alt=Independent sets for a star graph is an example of how vastly different the size of the maximal independent set can be to the maximum independent set. In this diagram, the [[star graph S8 has a maximal independent set of size 1 by selecting the internal node. It also has an maximal (and also maximum independent set) of size 8 by selecting each leave node instead.|thumb|Two independent sets for the star graph S8 show how vastly different in size two maximal independent sets (the right being maximum) can be. ]]

Two algorithmic problems are associated with MISs: finding a single MIS in a given graph and listing all MISs in a given graph.

Definition

For a graph , an independent set is a maximal independent set if for , one of the following is true:[1]

- where denotes the neighbors of

The above can be restated as a vertex either belongs to the independent set or has at least one neighbor vertex that belongs to the independent set. As a result, every edge of the graph has at least one endpoint not in . However, it is not true that every edge of the graph has at least one, or even one endpoint in

Any neighbor to a vertex in the independent set cannot be in because these vertices are disjoint by the independent set definition.

Related vertex sets

If S is a maximal independent set in some graph, it is a maximal clique or maximal complete subgraph in the complementary graph. A maximal clique is a set of vertices that induces a complete subgraph, and that is not a subset of the vertices of any larger complete subgraph. That is, it is a set S such that every pair of vertices in S is connected by an edge and every vertex not in S is missing an edge to at least one vertex in S. A graph may have many maximal cliques, of varying sizes; finding the largest of these is the maximum clique problem.

Some authors include maximality as part of the definition of a clique, and refer to maximal cliques simply as cliques.

The complement of a maximal independent set, that is, the set of vertices not belonging to the independent set, forms a minimal vertex cover. That is, the complement is a vertex cover, a set of vertices that includes at least one endpoint of each edge, and is minimal in the sense that none of its vertices can be removed while preserving the property that it is a cover. Minimal vertex covers have been studied in statistical mechanics in connection with the hard-sphere lattice gas model, a mathematical abstraction of fluid-solid state transitions.[2]

Every maximal independent set is a dominating set, a set of vertices such that every vertex in the graph either belongs to the set or is adjacent to the set. A set of vertices is a maximal independent set if and only if it is an independent dominating set.

Graph family characterizations

Certain graph families have also been characterized in terms of their maximal cliques or maximal independent sets. Examples include the maximal-clique irreducible and hereditary maximal-clique irreducible graphs. A graph is said to be maximal-clique irreducible if every maximal clique has an edge that belongs to no other maximal clique, and hereditary maximal-clique irreducible if the same property is true for every induced subgraph.[3] Hereditary maximal-clique irreducible graphs include triangle-free graphs, bipartite graphs, and interval graphs.

Cographs can be characterized as graphs in which every maximal clique intersects every maximal independent set, and in which the same property is true in all induced subgraphs.

Bounding the number of sets

(Moon Moser) showed that any graph with n vertices has at most 3n/3 maximal cliques. Complementarily, any graph with n vertices also has at most 3n/3 maximal independent sets. A graph with exactly 3n/3 maximal independent sets is easy to construct: simply take the disjoint union of n/3 triangle graphs. Any maximal independent set in this graph is formed by choosing one vertex from each triangle. The complementary graph, with exactly 3n/3 maximal cliques, is a special type of Turán graph; because of their connection with Moon and Moser's bound, these graphs are also sometimes called Moon-Moser graphs. Tighter bounds are possible if one limits the size of the maximal independent sets: the number of maximal independent sets of size k in any n-vertex graph is at most

The graphs achieving this bound are again Turán graphs.[4]

Certain families of graphs may, however, have much more restrictive bounds on the numbers of maximal independent sets or maximal cliques. If all n-vertex graphs in a family of graphs have O(n) edges, and if every subgraph of a graph in the family also belongs to the family, then each graph in the family can have at most O(n) maximal cliques, all of which have size O(1).[5] For instance, these conditions are true for the planar graphs: every n-vertex planar graph has at most 3n − 6 edges, and a subgraph of a planar graph is always planar, from which it follows that each planar graph has O(n) maximal cliques (of size at most four). Interval graphs and chordal graphs also have at most n maximal cliques, even though they are not always sparse graphs.

The number of maximal independent sets in n-vertex cycle graphs is given by the Perrin numbers, and the number of maximal independent sets in n-vertex path graphs is given by the Padovan sequence.[6] Therefore, both numbers are proportional to powers of 1.324718, the plastic ratio.

Finding a single maximal independent set

Sequential algorithm

Given a Graph G(V,E), it is easy to find a single MIS using the following algorithm:

- Initialize I to an empty set.

- While V is not empty:

- Choose a node v∈V;

- Add v to the set I;

- Remove from V the node v and all its neighbours.

- Return I.

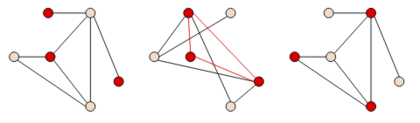

Random-selection parallel algorithm [Luby's Algorithm]

The following algorithm finds a MIS in time O(log n).[1][7][8]

- Initialize I to an empty set.

- While V is not empty:

- Choose a random set of vertices S ⊆ V, by selecting each vertex v independently with probability 1/(2d(v)), where d is the degree of v (the number of neighbours of v).

- For every edge in E, if both its endpoints are in the random set S, then remove from S the endpoint whose degree is lower (i.e. has fewer neighbours). Break ties arbitrarily, e.g. using a lexicographic order on the vertex names.

- Add the set S to I.

- Remove from V the set S and all the neighbours of nodes in S.

- Return I.

ANALYSIS: For each node v, divide its neighbours to lower neighbours (whose degree is lower than the degree of v) and higher neighbours (whose degree is higher than the degree of v), breaking ties as in the algorithm.

Call a node v bad if more than 2/3 of its neighbors are higher neighbours. Call an edge bad if both its endpoints are bad; otherwise the edge is good.

- At least 1/2 of all edges are always good. PROOF: Build a directed version of G by directing each edge to the node with the higher degree (breaking ties arbitrarily). So for every bad node, the number of out-going edges is more than 2 times the number of in-coming edges. So every bad edge, that enters a node v, can be matched to a distinct set of two edges that exit the node v. Hence the total number of edges is at least 2 times the number of bad edges.

- For every good node u, the probability that a neighbour of u is selected to S is at least a certain positive constant. PROOF: the probability that NO neighbour of u is selected to S is at most the probability that none of u's lower neighbours is selected. For each lower-neighbour v, the probability that it is not selected is (1-1/2d(v)), which is at most (1-1/2d(u)) (since d(u)>d(v)). The number of such neighbours is at least d(u)/3, since u is good. Hence the probability that no lower-neighbour is selected is at most 1-exp(-1/6).

- For every node u that is selected to S, the probability that u will be removed from S is at most 1/2. PROOF: This probability is at most the probability that a higher-neighbour of u is selected to S. For each higher-neighbour v, the probability that it is selected is at most 1/2d(v), which is at most 1/2d(u) (since d(v)>d(u)). By union bound, the probability that no higher-neighbour is selected is at most d(u)/2d(u) = 1/2.

- Hence, for every good node u, the probability that a neighbour of u is selected to S and remains in S is a certain positive constant. Hence, the probability that u is removed, in each step, is at least a positive constant.

- Hence, for every good edge e, the probability that e is removed, in each step, is at least a positive constant. So the number of good edges drops by at least a constant factor each step.

- Since at least half the edges are good, the total number of edges also drops by a constant factor each step.

- Hence, the number of steps is O(log m), where m is the number of edges. This is bounded by .

A worst-case graph, in which the average number of steps is , is a graph made of n/2 connected components, each with 2 nodes. The degree of all nodes is 1, so each node is selected with probability 1/2, and with probability 1/4 both nodes in a component are not chosen. Hence, the number of nodes drops by a factor of 4 each step, and the expected number of steps is .

Random-priority parallel algorithm

The following algorithm is better than the previous one in that at least one new node is always added in each connected component:[9][8]

- Initialize I to an empty set.

- While V is not empty, each node v does the following:

- Selects a random number r(v) in [0,1] and sends it to its neighbours;

- If r(v) is smaller than the numbers of all neighbours of v, then v inserts itself into I, removes itself from V and tells its neighbours about this;

- If v heard that one of its neighbours got into I, then v removes itself from V.

- Return I.

In every step, the node with the smallest number in each connected component always enters I, so there is always some progress. In particular, in the worst-case of the previous algorithm (n/2 connected components with 2 nodes each), a MIS will be found in a single step.

ANALYSIS:

- A node has probability at least of being removed. PROOF: For each edge connecting a pair of nodes , replace it with two directed edges, one from and the other . is now twice as large. For every pair of directed edges , define two events: and , pre-emptively removes and pre-emptively removes , respectively. The event occurs when and , where is a neighbor of and is neighbor . Recall that each node is given a random number in the same [0, 1] range. In a simple example with two disjoint nodes, each has probability of being smallest. If there are three disjoint nodes, each has probability of being smallest. In the case of , it has probability at least of being smallest because it is possible that a neighbor of is also the neighbor of , so a node becomes double counted. Using the same logic, the event also has probability at least of being removed.

- When the events and occur, they remove and directed outgoing edges, respectively. PROOF: In the event , when is removed, all neighboring nodes are also removed. The number of outgoing directed edges from removed is . With the same logic, removes directed outgoing edges.

- In each iteration of step 2, in expectation, half the edges are removed. PROOF: If the event happens then all neighbours of are removed; hence the expected number of edges removed due to this event is at least . The same is true for the reverse event , i.e. the expected number of edges removed is at least . Hence, for every undirected edge , the expected number of edges removed due to one of these nodes having smallest value is . Summing over all edges, , gives an expected number of edges removed every step, but each edge is counted twice (once per direction), giving edges removed in expectation every step.

- Hence, the expected run time of the algorithm is which is .[8]

Random-permutation parallel algorithm [Blelloch's Algorithm]

Instead of randomizing in each step, it is possible to randomize once, at the beginning of the algorithm, by fixing a random ordering on the nodes. Given this fixed ordering, the following parallel algorithm achieves exactly the same MIS as the #Sequential algorithm (i.e. the result is deterministic):[10]

- Initialize I to an empty set.

- While V is not empty:

- Let W be the set of vertices in V with no earlier neighbours (based on the fixed ordering);

- Add W to I;

- Remove from V the nodes in the set W and all their neighbours.

- Return I.

Between the totally sequential and the totally parallel algorithms, there is a continuum of algorithms that are partly sequential and partly parallel. Given a fixed ordering on the nodes and a factor δ∈(0,1], the following algorithm returns the same MIS:

- Initialize I to an empty set.

- While V is not empty:

- Select a factor δ∈(0,1].

- Let P be the set of δn nodes that are first in the fixed ordering.

- Let W be a MIS on P using the totally parallel algorithm.

- Add W to I;

- Remove from V all the nodes in the prefix P, and all the neighbours of nodes in the set W.

- Return I.

Setting δ=1/n gives the totally sequential algorithm; setting δ=1 gives the totally parallel algorithm.

ANALYSIS: With a proper selection of the parameter δ in the partially parallel algorithm, it is possible to guarantee that it finishes after at most log(n) calls to the fully parallel algorithm, and the number of steps in each call is at most log(n). Hence the total run-time of the partially parallel algorithm is . Hence the run-time of the fully parallel algorithm is also at most . The main proof steps are:

- If, in step i, we select , where D is the maximum degree of a node in the graph, then WHP all nodes remaining after step i have degree at most . Thus, after log(D) steps, all remaining nodes have degree 0 (since D<n), and can be removed in a single step.

- If, in any step, the degree of each node is at most d, and we select (for any constant C), then WHP the longest path in the directed graph determined by the fixed ordering has length . Hence the fully parallel algorithm takes at most steps (since the longest path is a worst-case bound on the number of steps in that algorithm).

- Combining these two facts gives that, if we select , then WHP the run-time of the partially parallel algorithm is .

Listing all maximal independent sets

An algorithm for listing all maximal independent sets or maximal cliques in a graph can be used as a subroutine for solving many NP-complete graph problems. Most obviously, the solutions to the maximum independent set problem, the maximum clique problem, and the minimum independent dominating problem must all be maximal independent sets or maximal cliques, and can be found by an algorithm that lists all maximal independent sets or maximal cliques and retains the ones with the largest or smallest size. Similarly, the minimum vertex cover can be found as the complement of one of the maximal independent sets. (Lawler 1976) observed that listing maximal independent sets can also be used to find 3-colorings of graphs: a graph can be 3-colored if and only if the complement of one of its maximal independent sets is bipartite. He used this approach not only for 3-coloring but as part of a more general graph coloring algorithm, and similar approaches to graph coloring have been refined by other authors since.[11] Other more complex problems can also be modeled as finding a clique or independent set of a specific type. This motivates the algorithmic problem of listing all maximal independent sets (or equivalently, all maximal cliques) efficiently.

It is straightforward to turn a proof of Moon and Moser's 3n/3 bound on the number of maximal independent sets into an algorithm that lists all such sets in time O(3n/3).[12] For graphs that have the largest possible number of maximal independent sets, this algorithm takes constant time per output set. However, an algorithm with this time bound can be highly inefficient for graphs with more limited numbers of independent sets. For this reason, many researchers have studied algorithms that list all maximal independent sets in polynomial time per output set.[13] The time per maximal independent set is proportional to that for matrix multiplication in dense graphs, or faster in various classes of sparse graphs.[14]

Counting maximal independent sets

The counting problem associated to maximal independent sets has been investigated in computational complexity theory. The problem asks, given an undirected graph, how many maximal independent sets it contains. This problem is #P-hard already when the input is restricted to be a bipartite graph.[15]

The problem is however tractable on some specific classes of graphs, for instance it is tractable on cographs.[16]

Parallelization of finding maximum independent sets

History

The maximal independent set problem was originally thought to be non-trivial to parallelize due to the fact that the lexicographical maximal independent set proved to be P-Complete; however, it has been shown that a deterministic parallel solution could be given by an reduction from either the maximum set packing or the maximal matching problem or by an reduction from the 2-satisfiability problem.[17][18] Typically, the structure of the algorithm given follows other parallel graph algorithms - that is they subdivide the graph into smaller local problems that are solvable in parallel by running an identical algorithm.

Initial research into the maximal independent set problem started on the PRAM model and has since expanded to produce results for distributed algorithms on computer clusters. The many challenges of designing distributed parallel algorithms apply in equal to the maximum independent set problem. In particular, finding an algorithm that exhibits efficient runtime and is optimal in data communication for subdividing the graph and merging the independent set.

Complexity class

It was shown in 1984 by Karp et al. that a deterministic parallel solution on PRAM to the maximal independent set belonged in the Nick's Class complexity zoo of .[19] That is to say, their algorithm finds a maximal independent set in using , where is the vertex set size. In the same paper, a randomized parallel solution was also provided with a runtime of using processors. Shortly after, Luby and Alon et al. independently improved on this result, bringing the maximal independent set problem into the realm of with an runtime using processors, where is the number of edges in the graph.[18][7][20] In order to show that their algorithm is in , they initially presented a randomized algorithm that uses processors but could be derandomized with an additional processors. Today, it remains an open question as to if the maximal independent set problem is in .

Communication and data exchange

Distributed maximal independent set algorithms are strongly influenced by algorithms on the PRAM model. The original work by Luby and Alon et al. has led to several distributed algorithms.[21][22][23][20] In terms of exchange of bits, these algorithms had a message size lower bound per round of bits and would require additional characteristics of the graph. For example, the size of the graph would need to be known or the maximum degree of neighboring vertices for a given vertex could be queried. In 2010, Métivier et al. reduced the required message size per round to , which is optimal and removed the need for any additional graph knowledge.[24]

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Luby's Algorithm, in: Lecture Notes for Randomized Algorithms, Last Updated by Eric Vigoda on February 2, 2006

- ↑ (Weigt Hartmann).

- ↑ Information System on Graph Class Inclusions: maximal clique irreducible graphs and hereditary maximal clique irreducible graphs .

- ↑ (Byskov 2003). For related earlier results see (Croitoru 1979) and (Eppstein 2003).

- ↑ (Chiba Nishizeki). Chiba and Nishizeki express the condition of having O(n) edges equivalently, in terms of the arboricity of the graphs in the family being constant.

- ↑ (Bisdorff Marichal); (Euler 2005); (Füredi 1987).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Luby, M. (1986). "A Simple Parallel Algorithm for the Maximal Independent Set Problem". SIAM Journal on Computing 15 (4): 1036–1053. doi:10.1137/0215074.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Principles of Distributed Computing (lecture 7)". ETH Zurich. http://dcg.ethz.ch/lectures/podc_allstars/lecture/chapter7.pdf.

- ↑ Métivier, Y.; Robson, J. M.; Saheb-Djahromi, N.; Zemmari, A. (2010). "An optimal bit complexity randomized distributed MIS algorithm". Distributed Computing 23 (5–6): 331. doi:10.1007/s00446-010-0121-5.

- ↑ Blelloch, Guy; Fineman, Jeremy; Shun, Julian (2012). "Greedy Sequential Maximal Independent Set and Matching are Parallel on Average". arXiv:1202.3205 [cs.DS].

- ↑ (Eppstein 2003); (Byskov 2003).

- ↑ (Eppstein 2003). For a matching bound for the widely used Bron–Kerbosch algorithm, see (Tomita Tanaka).

- ↑ (Bomze Budinich); (Eppstein 2005); (Jennings Motycková); (Johnson Yannakakis); (Lawler Lenstra); (Liang Dhall); (Makino Uno); (Mishra Pitt); (Stix 2004); (Tsukiyama Ide); (Yu Chen).

- ↑ (Makino Uno); (Eppstein 2005).

- ↑ Provan, J. Scott; Ball, Michael O. (November 1983). "The Complexity of Counting Cuts and of Computing the Probability that a Graph is Connected" (in en). SIAM Journal on Computing 12 (4): 777–788. doi:10.1137/0212053. ISSN 0097-5397. http://epubs.siam.org/doi/10.1137/0212053.

- ↑ Corneil, D. G.; Lerchs, H.; Burlingham, L. Stewart (1981-07-01). "Complement reducible graphs". Discrete Applied Mathematics 3 (3): 163–174. doi:10.1016/0166-218X(81)90013-5. ISSN 0166-218X.

- ↑ Cook, Stephen (June 1983). "An overview of computational complexity". Commun. ACM 26 (6): 400–408. doi:10.1145/358141.358144.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Barba, Luis (October 2012). "LITERATURE REVIEW: Parallel algorithms for the maximal independent set problem in graphs". http://cglab.ca/~lfbarba/parallel_algorithms/Literature_Review.pdf.

- ↑ Karp, R.M.; Wigderson, A. (1984). "A fast parallel algorithm for the maximal independent set problem". Proc. 16th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Alon, Noga; Laszlo, Babai; Alon, Itai (1986). "A fast and simple randomized parallel algorithm for the maximal independent set problem". Journal of Algorithms 7 (4): 567–583. doi:10.1016/0196-6774(86)90019-2.

- ↑ Peleg, David (2000). Distributed Computing: A Locality-Sensitive Approach. doi:10.1137/1.9780898719772. ISBN 978-0-89871-464-7.

- ↑ Lynch, N.A. (1996). "Distributed Algorithms". Morgan Kaufmann.

- ↑ Wattenhofer, R.. "Chapter 4: Maximal Independent Set". http://dcg.ethz.ch/lectures/fs08/distcomp/lecture/chapter4.pdf.

- ↑ Métivier, Y.; Robson, J. M.; Saheb-Djahromi, N.; Zemmari, A. (2010). "An optimal bit complexity randomized distributed MIS algorithm". Distributed Computing.

References

- Bisdorff, Raymond; Marichal, Jean-Luc (2008), "Counting non-isomorphic maximal independent sets of the n-cycle graph", Journal of Integer Sequences 11: 08.5.7, https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/journals/JIS/VOL11/Marichal/marichal.html.

- Bomze, I. M.; Budinich, M.; Pardalos, P. M.; Pelillo, M. (1999), "The maximum clique problem", Handbook of Combinatorial Optimization, 4, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 1–74.

- Byskov, J. M. (2003), "Algorithms for k-colouring and finding maximal independent sets", Proceedings of the Fourteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, Soda '03, pp. 456–457, ISBN 978-0-89871-538-5, http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=644182.

- "Arboricity and subgraph listing algorithms", SIAM Journal on Computing 14 (1): 210–223, 1985, doi:10.1137/0214017.

- Croitoru, C. (1979), "On stables in graphs", Proc. Third Coll. Operations Research, Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, pp. 55–60.

- Eppstein, D. (2003), "Small maximal independent sets and faster exact graph coloring", Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications 7 (2): 131–140, doi:10.7155/jgaa.00064, https://www.cs.brown.edu/publications/jgaa/accepted/2003/Eppstein2003.7.2.pdf.

- Eppstein, D. (2005). "All maximal independent sets and dynamic dominance for sparse graphs". 5. pp. 451–459. doi:10.1145/1597036.1597042..

- Erdős, P. (1966), "On cliques in graphs", Israel Journal of Mathematics 4 (4): 233–234, doi:10.1007/BF02771637.

- Euler, R. (2005), "The Fibonacci number of a grid graph and a new class of integer sequences", Journal of Integer Sequences 8 (2): 05.2.6, Bibcode: 2005JIntS...8...26E.

- "The number of maximal independent sets in connected graphs", Journal of Graph Theory 11 (4): 463–470, 1987, doi:10.1002/jgt.3190110403.

- Jennings, E.; Motycková, L. (1992), "A distributed algorithm for finding all maximal cliques in a network graph", Proc. First Latin American Symposium on Theoretical Informatics, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 583, Springer-Verlag, pp. 281–293

- "On generating all maximal independent sets", Information Processing Letters 27 (3): 119–123, 1988, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(88)90065-8.

- "A note on the complexity of the chromatic number problem", Information Processing Letters 5 (3): 66–67, 1976, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(76)90065-X, https://inria.hal.science/hal-04716389.

- "Generating all maximal independent sets: NP-hardness and polynomial time algorithms", SIAM Journal on Computing 9 (3): 558–565, 1980, doi:10.1137/0209042, https://pure.tue.nl/ws/files/2499168/Metis196442.pdf.

- Leung, J. Y.-T. (1984), "Fast algorithms for generating all maximal independent sets of interval, circular-arc and chordal graphs", Journal of Algorithms 5: 22–35, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(84)90037-3.

- Liang, Y. D.; Dhall, S. K.; Lakshmivarahan, S. (1991), "On the problem of finding all maximum weight independent sets in interval and circular arc graphs", Proceeding of the 1991 Symposium on Applied Computing, pp. 465–470, doi:10.1109/SOAC.1991.143921, ISBN 0-8186-2136-2

- Makino, K.; Uno, T. (2004), "New algorithms for enumerating all maximal cliques", Proc. Ninth Scandinavian Workshop on Algorithm Theory, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3111, Springer-Verlag, pp. 260–272, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-27810-8_23, ISBN 978-3-540-22339-9. ISBN 9783540223399, 9783540278108.

- Mishra, N.; Pitt, L. (1997), "Generating all maximal independent sets of bounded-degree hypergraphs", Proc. Tenth Conf. Computational Learning Theory, pp. 211–217, doi:10.1145/267460.267500, ISBN 978-0-89791-891-6.

- "On cliques in graphs", Israel Journal of Mathematics 3: 23–28, 1965, doi:10.1007/BF02760024.

- Stix, V. (2004), "Finding all maximal cliques in dynamic graphs", Computational Optimization and Applications 27 (2): 173–186, doi:10.1023/B:COAP.0000008651.28952.b6

- Tomita, E.; Tanaka, A.; Takahashi, H. (2006), "The worst-case time complexity for generating all maximal cliques and computational experiments", Theoretical Computer Science 363 (1): 28–42, doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2006.06.015.

- Tsukiyama, S.; Ide, M.; Ariyoshi, H.; Shirakawa, I. (1977), "A new algorithm for generating all the maximal independent sets", SIAM Journal on Computing 6 (3): 505–517, doi:10.1137/0206036.

- Weigt, Martin; Hartmann, Alexander K. (2001), "Minimal vertex covers on finite-connectivity random graphs: A hard-sphere lattice-gas picture", Phys. Rev. E 63 (5), doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.63.056127, PMID 11414981, Bibcode: 2001PhRvE..63e6127W.

- Yu, C.-W.; Chen, G.-H. (1993), "Generate all maximal independent sets in permutation graphs", Internat. J. Comput. Math. 47 (1–2): 1–8, doi:10.1080/00207169308804157.

de:Stabile Menge#Maximale stabile Menge

|