Medicine:NGLY1 deficiency

| NGLY1 deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | NGLY1-congenital disorder of deglycosylation |

| |

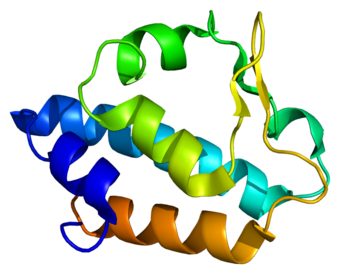

| N-glycanase 1, the affected protein | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

NGLY1 deficiency is a very rare genetic disorder caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in NGLY1. It is an autosomal recessive disorder. Errors in deglycosylation are responsible for the symptoms of this condition.[1] Clinically, most affected individuals display developmental delay, lack of tears, elevated liver transaminases and a movement disorder.[2] NGLY1 deficiency is difficult to diagnose, and most individuals have been identified by exome sequencing.

NGLY1 deficiency causes a dysfunction in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. NGLY1 encodes an enzyme, N-glycanase 1, that cleaves N-glycans. Without N-glycanase, N-glycosylated proteins that are misfolded in the endoplasmic reticulum cannot be degraded, and thus accumulate in the cytoplasm of cells.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

Four common findings have been identified in a majority of patients: developmental delay or intellectual disability of varying degrees, lack of or greatly reduced tears, elevated liver transaminases, and a complex movement disorder. The elevated liver enzymes often resolve in childhood. In addition, approximately 50% of patients described with NGLY1 deficiency have seizures, which can vary in their difficulty to control. Other symptoms that have been reported in affected individuals include sleep apnea, constipation, scoliosis, oral motor defects, auditory neuropathy and peripheral neuropathy.[2]

Diagnosis

NGLY1 deficiency can be suspected based on clinical findings, however confirmation of the diagnosis requires the identification of biallelic pathogenic variants in NGLY1 through genetic testing. Traditional screening tests utilized for congenital disorders of glycosylation, including carbohydrate deficient transferrin are not diagnostic in NGLY1 deficiency. To date all variants identified as being causative of NGLY1 deficiency have been sequence variants, rather than copy number variants. This spectrum may change as additional cases are identified.[2] A common nonsense variant (c.1201A>T (p.Arg401Ter)) accounts for approximately a third of pathogenic variants identified, and is associated with a more severe clinical course.[2]

There is also a biomarker for NGLY1 deficiency.[5][6] When the NGLY1 protein is missing or not functioning correctly, a specific molecule called GlcNAc-Asn (GNA) accumulates. GNA is elevated in individuals with NGLY1 deficiency compared to individuals without the disease.[6][5] Elevated GNA alone is not enough to confirm an NGLY1 deficiency diagnosis, but in combination with molecular genetic testing and clinical findings, it can provides additional support for NGLY1 deficiency.

Treatment

There is no cure for NGLY1 deficiency.[7] Supportive care is indicated for each patient based on their specific symptoms, and can include eye drops to manage the alacrima, pharmaceutical management of seizures, feeding therapy and physical therapy.[2] Most potential treatment options for NGLY1 deficiency are in the pre-clinical stages. These include enzyme replacement therapy, as well as ENGase inhibitors.[2]

Epidemiology

Forty-seven patients with confirmed NGLY1 deficiency have been reported in the medical literature.[8] Patient advocacy groups have reported approximately 100 patients have been identified. Currently, the majority of individuals reported with NGLY1 deficiency are of northern European descent, however this likely reflects an ascertainment bias in these early stages of the disorder. Affected individuals with African and Hispanic backgrounds have been identified.[2]

History

The first cases of NGLY1 deficiency were described in 2012.[1] NGLY1 deficiency has received a large amount of attention, despite its rarity, due to the children of two media-savvy families being afflicted.[9] The Wilseys, descendants of Dede Wilsey, founded the Grace Science Foundation[10] in honor of their daughter, while Matt Might and his wife founded the Bertrand Might Research Fund. These foundations have contributed millions of dollars to research efforts.[9][11]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) CONGENITAL DISORDER OF DEGLYCOSYLATION; CDDG -615273

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "NGLY1-Related Congenital Disorder of Deglycosylation". GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. February 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481554/.

- ↑ "Understanding human glycosylation disorders: biochemistry leads the charge". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 288 (10): 6936–45. March 2013. doi:10.1074/jbc.R112.429274. PMID 23329837.

- ↑ "Mutations in NGLY1 cause an inherited disorder of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway". Genetics in Medicine 16 (10): 751–8. October 2014. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.22. PMID 24651605.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Haijes, Hanneke A.; de Sain-van der Velden, Monique G. M.; Prinsen, Hubertus C. M. T.; Willems, Anke P.; van der Ham, Maria; Gerrits, Johan; Couse, Madeline H.; Friedman, Jan M. et al. (2019-08-01). "Aspartylglycosamine is a biomarker for NGLY1-CDDG, a congenital disorder of deglycosylation" (in en). Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 127 (4): 368–372. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.07.001. ISSN 1096-7192. PMID 31311714. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096719219303609.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mueller, William F; Zhu, Lei; Tan, Brandon; Dwight, Selina; Beahm, Brendan; Wilsey, Matt; Wechsler, Thomas; Mak, Justin et al. (2021-10-26). "GlcNAc-Asn (GNA) is a biomarker for NGLY1 deficiency". The Journal of Biochemistry 171 (mvab111): 177–186. doi:10.1093/jb/mvab111. ISSN 0021-924X. PMID 34697629.

- ↑ "About NGLY1". https://www.ngly1.org/about/.

- ↑ "50th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society". Annals of Neurology 90: S1–S173. 2021. doi:10.1002/ana.26177. ISSN 0364-5134. PMID 34570386. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ana.26177.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mnookin, Seth (14 July 2014). "One of a Kind". The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/07/21/one-of-a-kind-2.

- ↑ "Grace Science Foundation" (in en-US). https://gracescience.org/.

- ↑ "Our work - Grace Science Foundation". https://gracescience.org/our-work/.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|