Medicine:Placebo

A placebo (/pləˈsiːboʊ/ plə-SEE-boh) can be roughly defined as a sham medical treatment.[1][2] Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery,[3] and other procedures.[4]

Placebos are used in randomized clinical trials to test the efficacy of medical treatments. In a placebo-controlled trial, any change in the control group is known as the placebo response, and the difference between this and the result of no treatment is the placebo effect.[5] Placebos in clinical trials should ideally be indistinguishable from so-called verum treatments under investigation, except for the latter's particular hypothesized medicinal effect.[6] This is to shield test participants (with their consent) from knowing who is getting the placebo and who is getting the treatment under test, as patients' and clinicians' expectations of efficacy can influence results.[7][8]

The idea of a placebo effect was discussed in 18th century psychology,[9] but became more prominent in the 20th century. Modern studies find that placebos can affect some outcomes such as pain and nausea, but otherwise do not generally have important clinical effects.[10] Improvements that patients experience after being treated with a placebo can also be due to unrelated factors, such as regression to the mean (a statistical effect where an unusually high or low measurement is likely to be followed by a less extreme one).[11] The use of placebos in clinical medicine raises ethical concerns, especially if they are disguised as an active treatment, as this introduces dishonesty into the doctor–patient relationship and bypasses informed consent.[12]

Placebos are also popular because they can sometimes produce relief through psychological mechanisms (a phenomenon known as the "placebo effect"). They can affect how patients perceive their condition and encourage the body's chemical processes for relieving pain[11] and a few other symptoms,[13] but have no impact on the disease itself.[10][11]

Etymology and definition

The Latin term placebo means [I] shall be pleasing.[14][15]

The definition of placebo has been debated.[16] One definition states that a treatment process is a placebo when none of the characteristic treatment factors are effective (remedial or harmful) in the patient for a given disease.[17]

In a clinical trial, a placebo response is the measured response of subjects to a placebo; the placebo effect is the difference between that response and no treatment.[5] The placebo response may include improvements due to natural healing, declines due to natural disease progression, the tendency for people who were temporarily feeling either better or worse than usual to return to their average situations (regression toward the mean), and errors in the clinical trial records, which can make it appear that a change has happened when nothing has changed.[18] It is also part of the recorded response to any active medical intervention.[19]

Measurable placebo effects may be either objective (e.g. lowered blood pressure) or subjective (e.g. a lowered perception of pain).[1]

Effects

The placebo effect is well-documented phenomenon, though it remains widely misunderstood and surrounded by misconceptions.[2] Several studies have questioned its clinical relevance, fueling ongoing debate about its actual effectiveness. A 2001 meta-analysis of the placebo effect looked at trials in 40 different medical conditions, and concluded the only one where it had been shown to have a significant effect was for pain.[20] Another Cochrane review in 2010 suggested that placebo effects are apparent only in subjective, continuous measures, and in the treatment of pain and related conditions. The review found that placebos do not appear to affect the actual diseases, or outcomes that are not dependent on a patient's perception. The authors, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche, concluded that their study "did not find that placebo interventions have important clinical effects in general."[10] This interpretation has been subject to criticism, particularly due to concerns about the adequacy of the methodology used.[21][22][23][24][25] Recent research has linked placebo interventions to improved motor functions in patients with Parkinson's disease.[13][26][27] Other objective outcomes affected by placebos include immune and endocrine parameters,[28][29] end-organ functions regulated by the autonomic nervous system,[30] and sport performance.[31]

Measuring the extent of the placebo effect is difficult due to confounding factors.[32] For example, a patient may feel better after taking a placebo due to regression to the mean (i.e. a natural recovery or change in symptoms),[33][34][35] but this can be ruled out by comparing the placebo group with a no treatment group (as all the placebo research does). It is harder still to tell the difference between the placebo effect and the effects of response bias, observer bias and other flaws in trial methodology, as a trial comparing placebo treatment and no treatment will not be a blinded experiment.[10][33] In their 2010 meta-analysis of the placebo effect, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche argue that "even if there were no true effect of placebo, one would expect to record differences between placebo and no-treatment groups due to bias associated with lack of blinding."[10]

One way in which the magnitude of placebo analgesia can be measured is by conducting "open/hidden" studies, in which some patients receive an analgesic and are informed that they will be receiving it (open), while others are administered the same drug without their knowledge (hidden). Such studies have found that analgesics are considerably more effective when the patient knows they are receiving them.[36]

Factors influencing the power of the placebo effect

A review published in JAMA Psychiatry found that, in trials of antipsychotic medications, the change in response to receiving a placebo had increased significantly between 1960 and 2013. The review's authors identified several factors that could be responsible for this change, including inflation of baseline scores and enrollment of fewer severely ill patients.[37] Another analysis published in Pain in 2015 found that placebo responses had increased considerably in neuropathic pain clinical trials conducted in the United States from 1990 to 2013. The researchers suggested that this may be because such trials have "increased in study size and length" during this time period.[38]

Individual differences in personality traits may influence susceptibility to placebo and nocebo (negative placebo) effects. People with a more optimistic outlook tend to exhibit stronger placebo responses, while those with higher levels of anxiety are more likely to experience nocebo effects.[39]

Children seem to have a greater response than adults to placebos.[40]

The administration of the placebos can determine the placebo effect strength. Studies have found that taking more pills would strengthen the effect. Capsules appear to be more influential than pills, and injections are even stronger than capsules.[41]

Some studies have investigated the use of placebos where the patient is fully aware that the treatment is inert, known as an open-label placebo. Clinical trials found that open-label placebos may have positive effects in comparison to no treatment, which may open new avenues for treatments,[42] but a review of such trials noted that they were done with a small number of participants and hence should be interpreted with "caution" until further, better-controlled trials are conducted.[43] An updated 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis based on 11 studies also found a significant, albeit slightly smaller overall effect of open-label placebos, while noting that "research on OLPs is still in its infancy."[44]

If the person dispensing the placebo shows their care towards the patient, is friendly and sympathetic, or has a high expectation of a treatment's success, then the placebo is more effectual.[41]

Depression

In 2008, a meta-analysis led by psychologist Irving Kirsch, analyzing data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), concluded that 82% of the response to antidepressants was accounted for by placebos.[45] However, other authors expressed doubts about the used methods and the interpretation of the results, especially the use of 0.5 as the cut-off point for the effect size.[46] A complete reanalysis and recalculation based on the same FDA data found that the Kirsch study had "important flaws in the calculations."[47] The authors concluded that although a large percentage of the placebo response was due to expectancy, this was not true for the active drug.[47] Besides confirming drug effectiveness, they found that the drug effect was not related to depression severity.[47]

Another meta-analysis found that 79% of depressed patients receiving placebo remained well (for 12 weeks after an initial 6–8 weeks of successful therapy) compared to 93% of those receiving antidepressants. In the continuation phase however, patients on placebo relapsed significantly more often than patients on antidepressants.[48]

Negative effects

A phenomenon opposite to the placebo effect has also been observed. When an inactive substance or treatment is administered to a recipient who has an expectation of it having a negative impact, this intervention is known as a nocebo (Latin nocebo = "I shall harm").[49] A nocebo effect occurs when the recipient of an inert substance reports a negative effect or a worsening of symptoms, with the outcome resulting not from the substance itself, but from negative expectations about the treatment.[50][51]

Another negative consequence is that placebos can cause side-effects associated with real treatment.[52]

Withdrawal symptoms can also occur after placebo treatment. This was found, for example, after the discontinuation of the Women's Health Initiative study of hormone replacement therapy for menopause. Women had been on placebo for an average of 5.7 years. Moderate or severe withdrawal symptoms were reported by 4.8% of those on placebo compared to 21.3% of those on hormone replacement.[53]

Ethics

In research trials

Knowingly giving a person a placebo when there is an effective treatment available is a bioethically complex issue. While placebo-controlled trials might provide information about the effectiveness of a treatment, it denies some patients what could be the best available (if unproven) treatment. Informed consent is usually required for a study to be considered ethical, including the disclosure that some test subjects will receive placebo treatments.

The ethics of placebo-controlled studies have been debated in the revision process of the Declaration of Helsinki. Of particular concern has been the difference between trials comparing inert placebos with experimental treatments, versus comparing the best available treatment with an experimental treatment; and differences between trials in the sponsor's developed countries versus the trial's targeted developing countries.[54]

Some suggest that existing medical treatments should be used instead of placebos, to avoid having some patients not receive medicine during the trial.[55]

In medical practice

The practice of doctors prescribing placebos that are disguised as real medication is controversial. A chief concern is that it is deceptive and could harm the doctor–patient relationship in the long run. While some say that blanket consent, or the general consent to unspecified treatment given by patients beforehand, is ethical, others argue that patients should always obtain specific information about the name of the drug they are receiving, its side effects, and other treatment options.[56] This view is shared by some on the grounds of patient autonomy.[57] There are also concerns that legitimate doctors and pharmacists could open themselves up to charges of fraud or malpractice by using a placebo.[58] Critics also argued that using placebos can delay the proper diagnosis and treatment of serious medical conditions.[59]

Despite the abovementioned issues, 60% of surveyed physicians and head nurses reported using placebos in an Israeli study, with only 5% of respondents stating that placebo use should be strictly prohibited.[60] A British Medical Journal editorial said, "that a patient gets pain relief from a placebo does not imply that the pain is not real or organic in origin ...the use of the placebo for 'diagnosis' of whether or not pain is real is misguided."[61] A survey in the United States of more than 10,000 physicians came to the result that while 24% of physicians would prescribe a treatment that is a placebo simply because the patient wanted treatment, 58% would not, and for the remaining 18%, it would depend on the circumstances.[62]

Referring specifically to homeopathy, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Science and Technology Committee has stated:

In the Committee's view, homeopathy is a placebo treatment and the Government should have a policy on prescribing placebos. The Government is reluctant to address the appropriateness and ethics of prescribing placebos to patients, which usually relies on some degree of patient deception. Prescribing of placebos is not consistent with informed patient choice—which the Government claims is very important—as it means patients do not have all the information needed to make choice meaningful. A further issue is that the placebo effect is unreliable and unpredictable.[63]

In his 2008 book Bad Science, Ben Goldacre argues that instead of deceiving patients with placebos, doctors should use the placebo effect to enhance effective medicines.[64] Edzard Ernst has argued similarly that "As a good doctor you should be able to transmit a placebo effect through the compassion you show your patients."[65] In an opinion piece about homeopathy, Ernst argues that it is wrong to support alternative medicine on the basis that it can make patients feel better through the placebo effect.[66] His concerns are that it is deceitful and that the placebo effect is unreliable.[66] Goldacre also concludes that the placebo effect does not justify alternative medicine, arguing that unscientific medicine could lead to patients not receiving prevention advice.[64] Placebo researcher Fabrizio Benedetti also expresses concern over the potential for placebos to be used unethically, warning that there is an increase in "quackery" and that an "alternative industry that preys on the vulnerable" is developing.[67]

Mechanisms

The mechanism for how placebos could have effects is uncertain. From a sociocognitive perspective, intentional placebo response is attributed to the "ritual effect" that induces anticipation for transition to a better state.[68] A placebo presented as a stimulant may trigger an effect on heart rhythm and blood pressure, but when administered as a depressant, the opposite effect.[69]

Psychology

In psychology, the two main hypotheses of the placebo effect are expectancy theory and classical conditioning.[70]

In 1985, Irving Kirsch hypothesized that placebo effects are produced by the self-fulfilling effects of response expectancies, in which the belief that one will feel different leads a person to actually feel different.[71] According to this theory, the belief that one has received an active treatment can produce the subjective changes thought to be produced by the real treatment. Similarly, the appearance of effect can result from classical conditioning, wherein a placebo and an actual stimulus are used simultaneously until the placebo is associated with the effect from the actual stimulus.[72] Both conditioning and expectations play a role in placebo effect,[70] and make different kinds of contributions. Conditioning has a longer-lasting effect,[73] and can affect earlier stages of information processing.[74] Those who think a treatment will work display a stronger placebo effect than those who do not, as evidenced by a study of acupuncture.[75]

Additionally, motivation may contribute to the placebo effect. The active goals of an individual changes their somatic experience by altering the detection and interpretation of expectation-congruent symptoms, and by changing the behavioral strategies a person pursues.[76] Motivation may link to the meaning through which people experience illness and treatment. Such meaning is derived from the culture in which they live and which informs them about the nature of illness and how it responds to treatment.[citation needed]

Placebo analgesia

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia suggests links to the activation, and increased functional correlation between this activation, in the anterior cingulate, prefrontal, orbitofrontal and insular cortices, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, the brainstem's periaqueductal gray matter,[77][78] and the spinal cord.[79][80][81]

Since 1978, it has been known that placebo analgesia depends upon the release of endogenous opioids in the brain.[82] Such analgesic placebos activation changes processing lower down in the brain by enhancing the descending inhibition through the periaqueductal gray on spinal nociceptive reflexes, while the expectations of anti-analgesic nocebos acts in the opposite way to block this.[79]

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia has been summarized as showing that the placebo response is "mediated by 'top-down' processes dependent on frontal cortical areas that generate and maintain cognitive expectancies. Dopaminergic reward pathways may underlie these expectancies."[83] "Diseases lacking major 'top-down' or cortically based regulation may be less prone to placebo-related improvement."[84]

Brain and body

In conditioning, a neutral stimulus saccharin is paired in a drink with an agent that produces an unconditioned response. For example, that agent might be cyclophosphamide, which causes immunosuppression. After learning this pairing, the taste of saccharin by itself is able to cause immunosuppression, as a new conditioned response via neural top-down control.[85] Such conditioning has been found to affect a diverse variety of not just basic physiological processes in the immune system but ones such as serum iron levels, oxidative DNA damage levels, and insulin secretion. Recent reviews have argued that the placebo effect is due to top-down control by the brain for immunity[29] and pain.[86] Pacheco-López and colleagues have raised the possibility of "neocortical-sympathetic-immune axis providing neuroanatomical substrates that might explain the link between placebo/conditioned and placebo/expectation responses."[29]: 441 There has also been research aiming to understand underlying neurobiological mechanisms of action in pain relief, immunosuppression, Parkinson's disease and depression.[87]

Dopaminergic pathways have been implicated in the placebo response in pain and depression.[88]

Confounding factors

Placebo-controlled studies, as well as studies of the placebo effect itself, often fail to adequately identify confounding factors.[11][89] False impressions of placebo effects are caused by many factors including:[11][33][89][70][90]

- Regression to the mean (natural recovery or fluctuation of symptoms)

- Additional treatments

- Response bias from subjects, including scaling bias, answers of politeness, experimental subordination, conditioned answers;

- Reporting bias from experimenters, including misjudgment and irrelevant response variables.

- Non-inert ingredients of the placebo medication having an unintended physical effect

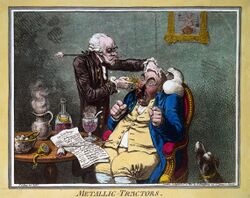

History

The word placebo was used in a medicinal context in the late 18th century to describe a "commonplace method or medicine" and in 1811 it was defined as "any medicine adapted more to please than to benefit the patient." Although this definition contained a derogatory implication[91] it did not necessarily imply that the remedy had no effect.[92]

It was recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries that drugs or remedies often were perceived to work best while they were still novel:[93]

We know that, in Paris, fashion imposes its dictates on medicine just as it does with everything else. Well, at one time, pyramidal elm bark[94] had a great reputation; it was taken as a powder, as an extract, as an elixir, even in baths. It was good for the nerves, the chest, the stomach—what can I say?— it was a true panacea. At the peak of the fad, one of Bouvard's [sic] patients asked him if it might not be a good idea to take some: "Take it, Madame", he replied, "and hurry up while it [still] cures." [dépêchez-vous pendant qu'elle guérit]

— Gaston de Lévis quoting Michel-Philippe Bouvart in the 1780s[95]

Placebos have featured in medical use until well into the twentieth century.[96] An influential 1955 study entitled The Powerful Placebo firmly established the idea that placebo effects were clinically important,[20] and were a result of the brain's role in physical health. A 1997 reassessment found no evidence of any placebo effect in the source data, as the study had not accounted for regression to the mean.[33][32][97]

Placebo-controlled studies

The placebo effect makes it more difficult to evaluate new treatments. Clinical trials control for this effect by including a group of subjects that receives a sham treatment. The subjects in such trials are blinded as to whether they receive the treatment or a placebo. If a person is given a placebo under one name, and they respond, they will respond in the same way on a later occasion to that placebo under that name but not if under another.[98]

Clinical trials are often double-blinded so that the researchers also do not know which test subjects are receiving the active or placebo treatment. The placebo effect in such clinical trials is weaker than in normal therapy since the subjects are not sure whether the treatment they are receiving is active.[99]

Cultural influences

Anthropologists argue that culture affects the ways in which individuals perceive medication, from different rituals and methods of healing, leading to placebo. Hahn and Kleinman (1983) propose an "ethnomedicogenic thesis" of placebo, wherein the ethnomedical system generates a feedback loop: cultural beliefs influence the disease state produced and effective treatments reinforce the belief system.[100]

"Symbolic effectiveness," a term coined by Claude Levi-Strauss relating to Shamanism, can result in a placebo effect as symbols displayed by the Shaman provide the patient with a form of "verbal expression" that can create a healing response within the patient.[101] Apud and Romaní say that Shamans are a sort of psychoanalytical therapist, while many other cultural rituals and practices such as religion provide a psychological effect on the medical outcome of the patient, resulting in a placebo effect.[102]

Hyland and Whalley conclude that carrying out a ritual, rather than believing in the ritual, may be an important factor in long-term placebo effects.[103] One anthropological perspective of rituals describe them as repetitive activities that intend to provide a sense of significance to one's life, giving them a sense that their bodily experience is in the hands of the world, out of their control as a result of patterns and rules, external to their own body.[104] Rituals are an attempt to "control nature," meaning that they can heal which results in the individual experience of placebo.[105]

See also

- E. Morton Jellinek § Recognition of placebo effect

- List of effects

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Placebo button

- Self-fulfilling prophecy[106]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ashar, Yoni K.; Chang, Luke J.; Wager, Tor D. (2017). "Brain Mechanisms of the Placebo Effect: An Affective Appraisal Account". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 13: 73–98. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093015. PMID 28375723.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lombardi, F (2025). "Shedding Light on the Placebo Effect". Think (Cambridge University Press) 24 (70): 43–48. doi:10.1017/S1477175625000223. https://philpapers.org/rec/LOMSLO.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Scott (18 February 2014). "The FDA Wants You for Sham Surgery". Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304680904579365414108916816.

- ↑ "Expectation enhances autonomic responses to stimulation of the human subthalamic limbic region". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 19 (6): 500–509. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2005.06.004. PMID 16055306.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The placebo response: an important part of treatment". Prescriber 17 (5): 16–22. 2006. doi:10.1002/psb.344.

- ↑ Blease, Charlotte; Annoni, Marco (April 2019). "Overcoming disagreement: a roadmap for placebo studies" (in en). Biology & Philosophy 34 (2). doi:10.1007/s10539-019-9671-5. ISSN 0169-3867. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331766597.

- ↑ "placebo". Dictionary.com. 9 April 2016. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/placebo.

- ↑ "placebo". TheFreeDictionary.com. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/placebo.

- ↑ Schwarz, K. A., & Pfister, R.: Scientific psychology in the 18th century: a historical rediscovery. In: Perspectives on Psychological Science, Nr. 11, pp. 399–407.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Hróbjartsson, Asbjørn, ed (January 2010). "Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 106 (1). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3. PMID 20091554. PMC 7156905. http://nordic.cochrane.org/sites/nordic.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/ResearchHighlights/Placebo%20interventions%20for%20all%20clinical%20conditions%20(Cochrane%20review).pdf. Retrieved 2018-06-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Placebo Effect". American Cancer Society. 10 April 2015. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/clinical-trials/placebo-effect.html.

- ↑ Newman, David H. (2008). Hippocrates' Shadow. Scribner. pp. 134–159. ISBN 978-1-4165-5153-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Quattrone, Aldo; Barbagallo, Gaetano; Cerasa, Antonio; Stoessl, A. Jon (August 2018). "Neurobiology of placebo effect in Parkinson's disease: What we have learned and where we are going". Movement Disorders 33 (8): 1213–1227. doi:10.1002/mds.27438. ISSN 1531-8257. PMID 30230624.

- ↑ "Placebo (origins of technical term)". https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Placebo+(origins+of+technical+term).

- ↑ Jacobs B (April 2000). "Biblical origins of placebo". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 93 (4): 213–214. doi:10.1177/014107680009300419. PMID 10844895.

- ↑ Blease, Charlotte; Annoni, Marco (2019-03-14). "Overcoming disagreement: a roadmap for placebo studies" (in en). Biology & Philosophy 34 (2): 18. doi:10.1007/s10539-019-9671-5. ISSN 1572-8404.

- ↑ Howick, Jeremy (2017). "The relativity of 'placebos': defending a modified version of Grünbaum's definition". Synthese 194 (4): 1363–1396. doi:10.1007/s11229-015-1001-0. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11229-015-1001-0.

- ↑ Kaptchuk, Ted J; Hemond, Christopher C; Miller, Franklin G (2020-07-20). "Placebos in chronic pain: evidence, theory, ethics, and use in clinical practice" (in en). BMJ 370. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1668. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32690477.

- ↑ "The powerful placebo in cough studies?". Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 15 (3): 303–308. 2002. doi:10.1006/pupt.2002.0364. PMID 12099783.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment". The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (21): 1594–1602. May 2001. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. PMID 11372012.

- ↑ Vase, Lene; Petersen, Gitte Laue; Riley, Joseph L.; Price, Donald D. (2009-09-01). "Factors contributing to large analgesic effects in placebo mechanism studies conducted between 2002 and 2007". PAIN 145 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.008. ISSN 0304-3959. PMID 19559529. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304395909002164.

- ↑ Spiegel, D; Kraemer, H; Carlson, R W (2001-10-01). "Is the placebo powerless". The New England Journal of Medicine 345 (17): 1276; author reply 1278–9. doi:10.1056/nejm200110253451712. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 11680452.

- ↑ "Apples, oranges, and placebos: Heterogeneity in a meta-analysis of placebo effects". Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-05525-013.

- ↑ Wampold, Bruce E.; Imel, Zac E.; Minami, Takuya (April 2007). "The story of placebo effects in medicine: Evidence in context" (in en). Journal of Clinical Psychology 63 (4): 379–390. doi:10.1002/jclp.20354. PMID 17279527. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jclp.20354.

- ↑ Wampold, Bruce E.; Minami, Takuya; Tierney, Sandra Callen; Baskin, Thomas W.; Bhati, Kuldhir S. (July 2005). "The placebo is powerful: Estimating placebo effects in medicine and psychotherapy from randomized clinical trials" (in en). Journal of Clinical Psychology 61 (7): 835–854. doi:10.1002/jclp.20129. ISSN 0021-9762. PMID 15827993. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jclp.20129.

- ↑ Gross, Liza (February 2017). "Putting placebos to the test". PLOS Biology 15 (2). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001998. ISSN 1545-7885. PMID 28222121.

- ↑ Enck, Paul; Bingel, Ulrike; Schedlowski, Manfred; Rief, Winfried (March 2013). "The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize?" (in en). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 12 (3): 191–204. doi:10.1038/nrd3923. ISSN 1474-1776. PMID 23449306. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235756144.

- ↑ Tekampe, Judith; van Middendorp, Henriët; Meeuwis, Stefanie H.; van Leusden, Jelle W.R.; Pacheco-López, Gustavo; Hermus, Ad R.M.M.; Evers, Andrea W.M. (2017-02-10). "Conditioning Immune and Endocrine Parameters in Humans: A Systematic Review". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 86 (2): 99–107. doi:10.1159/000449470. ISSN 0033-3190. PMID 28183096.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "Expectations and associations that heal: Immunomodulatory placebo effects and its neurobiology". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 20 (5): 430–46. September 2006. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2006.05.003. PMID 16887325.

- ↑ Meissner, Karin (2011-06-27). "The placebo effect and the autonomic nervous system: evidence for an intimate relationship". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366 (1572): 1808–1817. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0403. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 21576138.

- ↑ Hurst, Philip; Schipof-Godart, Lieke; Szabo, Attila; Raglin, John; Hettinga, Florentina; Roelands, Bart; Lane, Andrew; Foad, Abby et al. (2020-03-15). "The Placebo and Nocebo effect on sports performance: A systematic review" (in en). European Journal of Sport Science 20 (3): 279–292. doi:10.1080/17461391.2019.1655098. ISSN 1746-1391. PMID 31414966. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2019.1655098.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Is the placebo powerless? Update of a systematic review with 52 new randomized trials comparing placebo with no treatment". Journal of Internal Medicine 256 (2): 91–100. August 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01355.x. PMID 15257721. Gøtzsche's biographical article has further references related to this work.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 "The powerful placebo effect: fact or fiction?". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 50 (12): 1311–8. December 1997. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00203-5. PMID 9449934.

- ↑ "How much of the placebo 'effect' is really statistical regression?". Statistics in Medicine 2 (4): 417–27. 1983. doi:10.1002/sim.4780020401. PMID 6369471.

- ↑ "Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it". International Journal of Epidemiology 34 (1): 215–20. February 2005. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh299. PMID 15333621.

- ↑ "A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought". Annual Review of Psychology 59 (1): 565–90. 2008. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.113006.095941. PMID 17550344.

- ↑ "Placebo response in antipsychotic clinical trials: a meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry 71 (12): 1409–21. December 2014. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1319. PMID 25321611.

- ↑ "Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain". Pain 156 (12): 2616–26. December 2015. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000333. PMID 26307858.

- Lay summary in: The Placebo Effect Is Getting Stronger — But Only in the U.S.. October 9, 2015. https://www.thecut.com/2015/10/placebo-effect-is-getting-stronger.html.

- ↑ Kern, Alexandra; Kramm, Christoph; Witt, Claudia M.; Barth, Jürgen (2020). "The influence of personality traits on the placebo/nocebo response". Journal of Psychosomatic Research (Elsevier BV) 128. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109866. ISSN 0022-3999. PMID 31760341. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/183343/9/Kern_et_al._%282020%29_Manuskript.pdf. Retrieved 2025-04-09.

- ↑ Klassen, Terry, ed (August 2008). "Greater response to placebo in children than in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis in drug-resistant partial epilepsy". PLOS Medicine 5 (8). doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050166. PMID 18700812.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Rosenberg, Robin; Kosslyn, Stephen (2010) (in en). Abnormal Psychology. Worth Publishers. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4292-6356-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Nh-RAAACAAJ. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ Blease, CR; Bernstein, MH; Locher, C (26 June 2019). "Open-label placebo clinical trials: is it the rationale, the interaction or the pill?". BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 25 (5): bmjebm–2019–111209. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111209. PMID 31243047.

- ↑ Charlesworth, James E.G.; Petkovic, Grace; Kelley, John M.; Hunter, Monika; Onakpoya, Igho; Roberts, Nia; Miller, Franklin G.; Howick, Jeremy (2017). "Effects of placebos without deception compared with no treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10 (2): 97–107. doi:10.1111/jebm.12251. PMID 28452193.

- ↑ von Wernsdorff, Melina; Loef, Martin; Tuschen-Caffier, Brunna; Schmidt, Stefan (2023). "Effects of open-label placebos in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports 11 (1): 3855. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83148-6. PMID 33594150. Bibcode: 2021NatSR..11.3855V.

- ↑ "Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLOS Medicine 5 (2). February 2008. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMID 18303940.

- ↑ "Efficacy of antidepressants". BMJ 336 (7643): 516–7. March 2008. doi:10.1136/bmj.39510.531597.80. PMID 18319297.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 14 (3): 405–12. April 2011. doi:10.1017/S1461145710000957. PMID 20800012.

- ↑ "The persistence of the placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research 42 (10): 791–6. August 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.10.004. PMID 18036616.

- ↑ "nocebo". Merriam-Webster Incorporated. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/nocebo.

- ↑ "Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 109 (26): 459–65. June 2012. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0459. PMID 22833756.

- ↑ "The Nocebo Effect". Priory.com. 10 February 2007. http://priory.com/medicine/Nocebo.htm.

- ↑ "Placebo induced side effects". Journal of Operational Psychiatry 6: 43–6. 1974. http://psycnet.apa.org/?fa=main.doiLanding&uid=1977-04006-001.

- ↑ "Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin". JAMA 294 (2): 183–93. July 2005. doi:10.1001/jama.294.2.183. PMID 16014592.

- ↑ "The improper use of research placebos". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 16 (6): 1041–4. December 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01246.x. PMID 20663001. https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/165152.

- ↑ "The placebo problem remains". Archives of General Psychiatry 57 (4): 321–2. April 2000. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.321. PMID 10768689.

- ↑ "Reexamination of the ethics of placebo use in clinical practice". Bioethics 27 (4): 186–93. May 2013. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01943.x. PMID 22296589.

- ↑ "The ethics of prescription of placebos to patients with major depressive disorder". Chinese Medical Journal 128 (11): 1555–7. June 2015. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.157699. PMID 26021517.

- ↑ Malani, Anup (2008). "Regulation with Placebo Effects". Chicago Unbound 58 (3): 411–72. PMID 19353835. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2640&context=journal_articles. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 82 (1): 69–75. January 2007. doi:10.4065/82.1.69. PMID 17285788.

- ↑ Nitzan, Uriel; Lichtenberg, Pesach (2004-10-23). "Questionnaire survey on use of placebo". BMJ: British Medical Journal 329 (7472): 944–946. doi:10.1136/bmj.38236.646678.55. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 15377572.

- ↑ "Placebos in practice". BMJ 329 (7472): 927–8. October 2004. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7472.927. PMID 15499085.

- ↑ Doctors Struggle With Tougher-Than-Ever Dilemmas: Other Ethical Issues Author: Leslie Kane. 11/11/2010

- ↑ "Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy". http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-archive/science-technology/s-t-homeopathy-inquiry/.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Goldacre, Ben (2008). "5: The Placebo Effect". Bad Science. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-724019-7.

- ↑ Rimmer, Abi (January 2018). "Empathy and ethics: five minutes with Edzard Ernst". The BMJ 360 (1): k309. doi:10.1136/bmj.k309. PMID 29371199.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "No to homeopathy placebo". The Guardian. 22 February 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/feb/22/science-homeopathy-clinical-trials.

- ↑ Benedetti, Fabrizio (3 March 2022). "The science of placebos is fuelling quackery". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-030222-3. https://knowablemagazine.org/article/society/2022/science-placebos-fuelling-quackery. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ Goli, Farzad; Farzanegan, Mahboubeh (2016), "The Ritual Effect: The Healing Response to Forms and Performs", Biosemiotic Medicine, Studies in Neuroscience, Consciousness and Spirituality (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 5: pp. 117–132, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-35092-9_5, ISBN 978-3-319-35091-2

- ↑ Harrington A, ed (1997). "Specifying non-specifics: Psychological mechanism of the placebo effect". The Placebo Effect: An Interdisciplinary Exploration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 166–86. ISBN 978-0-674-66986-4.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 "The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate". Psychological Bulletin 130 (2): 324–40. March 2004. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.324. PMID 14979775.

- ↑ "Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior". American Psychologist 40 (11): 1189–1202. 1985. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1189.

- ↑ "Conditioned response models of placebo phenomena: further support". Pain 38 (1): 109–16. July 1989. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90080-8. PMID 2780058.

- ↑ "Classical conditioning and expectancy in placebo hypoalgesia: a randomized controlled study in patients with atopic dermatitis and persons with healthy skin". Pain 128 (1–2): 31–9. March 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.025. PMID 17030095.

- ↑ "Learning potentiates neurophysiological and behavioral placebo analgesic responses". Pain 139 (2): 306–14. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.021. PMID 18538928.

- ↑ "The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain". Pain 128 (3): 264–71. April 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. PMID 17257756.

- ↑ "Goal activation, expectations, and the placebo effect". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (2): 143–59. August 2005. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.143. PMID 16162050.

- ↑ "Placebo effects: clinical aspects and neurobiology". Brain 131 (Pt 11): 2812–23. November 2008. doi:10.1093/brain/awn116. PMID 18567924.

- ↑ "Understanding the placebo effect: contributions from neuroimaging". Molecular Imaging and Biology 9 (4): 176–85. 2007. doi:10.1007/s11307-007-0086-3. PMID 17334853.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "Descending analgesia--when the spine echoes what the brain expects". Pain 130 (1–2): 137–43. July 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.11.011. PMID 17215080.

- ↑ "Neuroimaging study of placebo analgesia in humans". Neuroscience Bulletin 25 (5): 277–82. October 2009. doi:10.1007/s12264-009-0907-2. PMID 19784082.

- ↑ "Neurobiological mechanisms of placebo responses". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1156 (1): 198–210. March 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04424.x. PMID 19338509. Bibcode: 2009NYASA1156..198Z.

- ↑ "The mechanism of placebo analgesia". Lancet 2 (8091): 654–7. September 1978. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92762-9. PMID 80579.

- ↑ "Imaging the placebo response: a neurofunctional review". European Neuropsychopharmacology 18 (7): 473–85. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.03.002. PMID 18495442.

- ↑ "The placebo treatments in neurosciences: New insights from clinical and neuroimaging studies". Neurology 71 (9): 677–84. August 2008. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000324635.49971.3d. PMID 18725593.

- ↑ "Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression". Psychosomatic Medicine 37 (4): 333–40. 1975. doi:10.1097/00006842-197507000-00007. PMID 1162023.

- ↑ "Placebos and painkillers: is mind as real as matter?". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 6 (7): 545–52. July 2005. doi:10.1038/nrn1705. PMID 15995725.

- ↑ "Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect". The Journal of Neuroscience 25 (45): 10390–402. November 2005. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3458-05.2005. PMID 16280578.

- ↑ "Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of the placebo effect in neurological and psychiatric conditions". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 140 (3): 306–18. December 2013. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.009. PMID 23880289.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Placebo effect studies are susceptible to response bias and to other types of biases". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64 (11): 1223–9. November 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.008. PMID 21524568.

- ↑ "What's in placebos: who knows? Analysis of randomized, controlled trials". Annals of Internal Medicine 153 (8): 532–5. October 2010. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00010. PMID 20956710.

- ↑ Shapiro AK (1968). "Semantics of the placebo". Psychiatric Quarterly 42 (4): 653–695. doi:10.1007/BF01564309. PMID 4891851.

- ↑ Kaptchuk TJ (June 1998). "Powerful placebo: the dark side of the randomised controlled trial". The Lancet 351 (9117): 1722–1725. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10111-8. PMID 9734904.

- ↑ Arthur K. Shapiro, Elaine Shapiro, The Powerful Placebo: From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician, 2006, ISBN 1421401347, chapter "The Placebo Effect in Medical History"

- ↑ the inner bark of Ulmus campestris: Simon Morelot, Cours élémentaire d'histoire naturelle pharmaceutique..., 1800, p. 349 "the elm, pompously named pyramidal...it had an ephemeral reputation"; Georges Dujardin-Beaumetz, Formulaire pratique de thérapeutique et de pharmacologie, 1893, p. 260

- ↑ Gaston de Lévis, Souvenirs et portraits, 1780–1789, 1813, p. 240

- ↑ "Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 92 (10): 511–515. October 1999. doi:10.1177/014107689909201005. PMID 10692902.

- ↑ Stoddart, Charlotte, How placebo effect went mainstream, Knowable Magazine, June 27, 2023

- ↑ "Consistency of the placebo effect". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (5): 537–541. May 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.007. PMID 18440407.

- ↑ "A comparison of placebo effects in clinical analgesic trials versus studies of placebo analgesia". Pain 99 (3): 443–452. October 2002. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00205-1. PMID 12406519.

- ↑ Hahn, R. A., & Kleinman, A. (1983). Belief as Pathogen, Belief as Medicine: "Voodoo Death" and the "Placebo Phenomenon" in Anthropological Perspective. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 14(4), 3–19.

- ↑ Apud, I., & Romaní, O. (2019). Medical anthropology and symbolic cure: from the placebo to cultures of meaningful healing. Anthropology & Medicine, 27(2), 160–175. https://doi-org.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/10.1080/13648470.2019.1649542

- ↑ Apud, I., & Romaní, O. (2019). Medical anthropology and symbolic cure: from the placebo to cultures of meaningful healing. Anthropology & Medicine, 27(2), 160–175. https://doi-org.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/10.1080/13648470.2019.1649542

- ↑ Ostenfeld-Rosenthal, A. M. (2012). Energy healing and the placebo effect. An anthropological perspective on the placebo effect. Anthropology & Medicine, 19(3), 327–338. https://doi-org.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/10.1080/13648470.2011.646943

- ↑ Brody, H. (2010). Ritual, medicine, and the placebo response. The problem of ritual efficacy, 151, 167.

- ↑ Brody, H. (2010). Ritual, medicine, and the placebo response. The problem of ritual efficacy, 151, 167.

- ↑ Benedetti, Fabrizio (2008-10-16). Placebo Effects. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199559121.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-955912-1.

Further reading

- Benedetti, Fabrizio (2009). Placebo Effects. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920764-6.

- Benedetti, Fabrizio (2020). The Patient's Brain: The Neuroscience Behind the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968071-5

{{isbn}}: Checkisbnvalue: checksum (help) - Hall, Kathryn T (2022). Placebos. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54425-2.

- Colloca, Luana (2018-04-20). Neurobiology of the placebo effect. Part I. Cambridge, MA. ISBN 978-0-12-814326-1. OCLC 1032303151.

- Colloca, Luana (2018-08-23). Neurobiology of the placebo effect. Part II (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA, United States. ISBN 978-0-12-815417-5. OCLC 1049800273.

- Raz, Amir, and Campbell, Cory (2016). Placebo Talk: How Talking About Placebos Influences Their Effects. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968070-8.

- Raz, Amir (2023). The Suggestible Brain: Unraveling the Influence of Belief and Expectation on the Mind and Body. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-51497-6.

- Erik, Vance (2016). Suggestible You: The Curious Science of Your Brain's Ability to Deceive, Transform, and Heal. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-1789-0.

- Francis, Gavin, "What Do You Expect?" (review of Kathryn T. Hall, Placebos, MIT Press, 2022; 201 pp; and Jeremy Howick, The Power of Placebos: How the Science of Placebos and Nocebose Can Improve Health Care, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023; 304 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXXII, no. 11 (26 June 2025), pp. 30–32. "[O]ur culture has become so medicalized and reductionistic that warm and empathetic care, with its immense proven benefits for the way that a patient feels and heals, has been deprioritized to an optional extra rather than a core element of medicine. A rebalancing is in order: doctors need more time with their patients and, yes, more use of honest placebos – because they work." (p. 32.)

External links

- Program in Placebo Studies & Therapeutic Encounter (PiPS) (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School)

|