Medicine:Depression (mood)

| Depression | |

|---|---|

| |

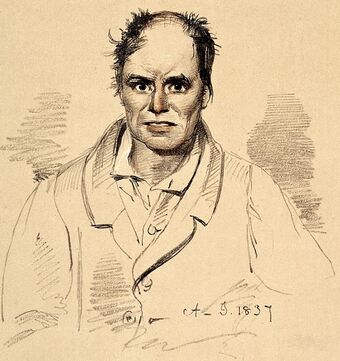

| Lithograph of a man diagnosed as suffering from melancholia with strong suicidal tendency (1892) | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Psychology |

| Symptoms | Low mood, aversion to activity, loss of interest, loss of feeling pleasure |

| Risk factors | Stigma of mental health disorder.[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Patient Health Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory |

| Differential diagnosis | Anxiety, Bipolar Disorder, Borderline personality disorder |

| Prevention | Social connections, Physical activity |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, Psychopharmacology |

Depression is a state of low mood and aversion to activity.[2] Classified medically as a mental and behavioral disorder,[3] the experience of depression affects a person's thoughts, behavior, motivation, feelings, and sense of well-being.[4] The core symptom of depression is said to be anhedonia, which refers to loss of interest or a loss of feeling of pleasure in certain activities that usually bring joy to people.[5] Depressed mood is a symptom of some mood disorders such as major depressive disorder or dysthymia;[6] it is a normal temporary reaction to life events, such as the loss of a loved one; and it is also a symptom of some physical diseases and a side effect of some drugs and medical treatments. It may feature sadness, difficulty in thinking and concentration and a significant increase or decrease in appetite and time spent sleeping. People experiencing depression may have feelings of dejection, hopelessness and suicidal thoughts. It can either be short term or long term.

Factors

Life events

Adversity in childhood, such as bereavement, neglect, mental abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or unequal parental treatment of siblings can contribute to depression in adulthood.[7][8] Childhood physical or sexual abuse in particular significantly correlates with the likelihood of experiencing depression over the victim's lifetime.[9]

Life events and changes that may influence depressed moods include (but are not limited to): childbirth, menopause, financial difficulties, unemployment, stress (such as from work, education, family, living conditions etc.), a medical diagnosis (cancer, HIV, etc.), bullying, loss of a loved one, natural disasters, social isolation, rape, relationship troubles, jealousy, separation, or catastrophic injury.[10][11][12][13][14] Adolescents may be especially prone to experiencing a depressed mood following social rejection, peer pressure, or bullying.[15]

Globally, more than 264 million people of all ages suffer from depression.[16] The global pandemic of COVID-19 has negatively impacted upon many individuals’ mental health, causing levels of depression to surge, reaching devastating heights. A study conducted by the University of Surrey in Autumn 2019 and May/June 2020 looked into the impact of COVID-19 upon young peoples mental health. This study is published in the Journal of Psychiatry Research Report.[17] The study showed a significant rise in depression symptoms and a reduction in overall wellbeing during lockdown (May/June 2020) compared to the previous Autumn (2019). Levels of clinical depression in those surveyed in the study were found to have more than doubled, rising from 14.9 per cent in Autumn 2019 to 34.7 per cent in May/June 2020.[18] This study further emphasises the correlation that certain life events have with developing depression.

Personality

Changes in personality or in one's social environment can affect levels of depression. High scores on the personality domain neuroticism make the development of depressive symptoms as well as all kinds of depression diagnoses more likely,[19] and depression is associated with low extraversion.[20] Other personality indicators could be: temporary but rapid mood changes, short term hopelessness, loss of interest in activities that used to be of a part of one's life, sleep disruption, withdrawal from previous social life, appetite changes, and difficulty concentrating.[21]

Alcoholism

Alcohol can be a depressant which slows down some regions of the brain, like the prefrontal and temporal cortex, negatively affecting rationality and memory.[22] It also lowers the level of serotonin in the brain, which could potentially lead to higher chances of depressive mood.[23]

The connection between the amount of alcohol intake, level of depressed mood, and how it affects the risks of experiencing consequences from alcoholism, were studied in a research done on college students. The study used 4 latent, distinct profiles of different alcohol intake and level of depression; Mild or Moderate Depression, and Heavy or Severe Drinkers. Other indicators consisting of social factors and individual behaviors were also taken into consideration in the research. Results showed that the level of depression as an emotion negatively affected the amount of risky behavior and consequence from drinking, while having an inverse relationship with protective behavioral strategies, which are behavioral actions taken by oneself for protection from the relative harm of alcohol intake. Having an elevated level of depressed mood does therefore lead to greater consequences from drinking.[24]

Bullying

Social abuse, such as bullying, are defined as actions of singling out and causing harm on vulnerable individuals. In order to capture a day-to-day observation of the relationship between the damaging effects of social abuse, the victim's mental health and depressive mood, a study was conducted on whether individuals would have a higher level of depressed mood when exposed to daily acts of negative behavior. The result concluded that being exposed daily to abusive behaviors such as bullying has a positive relationship to depressed mood on the same day.

The study has also gone beyond to compare the level of depressive mood between the victims and non-victims of the daily bullying. Although victims were predicted to have a higher level of depressive mood, the results have shown otherwise that exposure to negative acts has led to similar levels of depressive mood, regardless of the victim status. The results therefore have concluded that bystanders and non-victims feel as equally depressed as the victim when being exposed to acts such as social abuse.[25]

Medical treatments

Depression may also be the result of healthcare, such as with medication induced depression. Therapies associated with depression include interferon therapy, beta-blockers, isotretinoin, contraceptives,[26] anticonvulsants, antimigraine drugs, antipsychotics, hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist,[27] magnetic stimulation to brain and electric therapy.

Substance-induced

Several drugs of abuse can cause or exacerbate depression, whether in intoxication, withdrawal, and from chronic use. These include alcohol, sedatives (including prescription benzodiazepines), opioids (including prescription pain killers and illicit drugs such as heroin), stimulants (such as cocaine and amphetamines), hallucinogens, and inhalants.[28]

Non-psychiatric illnesses

Depressed mood can be the result of a number of infectious diseases, nutritional deficiencies, neurological conditions,[29] and physiological problems, including hypoandrogenism (in men), Addison's disease, Cushing's syndrome, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, chronic pain, stroke,[30] diabetes,[31] and cancer.[32]

Psychiatric syndromes

A number of psychiatric syndromes feature depressed mood as a main symptom. The mood disorders are a group of disorders considered to be primary disturbances of mood. These include major depressive disorder (MDD; commonly called major depression or clinical depression) where a person has at least two weeks of depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities; and dysthymia, a state of chronic depressed mood, the symptoms of which do not meet the severity of a major depressive episode. Another mood disorder, bipolar disorder, features one or more episodes of abnormally elevated mood, cognition, and energy levels, but may also involve one or more episodes of depression.[33] When the course of depressive episodes follows a seasonal pattern, the disorder (major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, etc.) may be described as a seasonal affective disorder. Outside the mood disorders: borderline personality disorder often features an extremely intense depressive mood; adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode;[34]: 355 and posttraumatic stress disorder, a mental disorder that sometimes follows trauma, is commonly accompanied by depressed mood.[35]

Historical legacy

Researchers have begun to conceptualize ways in which the historical legacies of racism and colonialism may create depressive conditions.[36][37]

Measures

Measures of depression as an emotional disorder include, but are not limited to: Beck Depression Inventory-11 and the 9-item depression scale in the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).[38] Both of these measures are psychological tests that ask personal questions of the participant, and have mostly been used to measure the severity of depression. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a self-report scale that helps a therapist identify the patterns of depression symptoms and monitor recovery. The responses on this scale can be discussed in therapy to devise interventions for the most distressing symptoms of depression.[5] Several studies, however, have used these measures to also determine healthy individuals who are not suffering from depression as a mental disorder, but as an occasional mood disorder. This is substantiated by the fact that depression as an emotional disorder displays similar symptoms to minimal depression and low levels of mental disorders such as major depressive disorder; therefore, researchers were able to use the same measure interchangeably. In terms of the scale, participants scoring between 0–13 and 0–4 respectively were considered healthy individuals.[24]

Another measure of depressed mood would be the IWP Multi-affect Indicator.[39] It is a psychological test that indicates various emotions, such as enthusiasm and depression, and asks for the degree of the emotions that the participants have felt in the past week. There are studies that have used lesser items from the IWP Multi-affect Indicator which was then scaled down to daily levels to measure the daily levels of depression as an emotional disorder.[25]

Creative thinking

Divergent thinking is defined as a thought process that generates creativity in ideas by exploring many possible solutions. Having a depressed mood will significantly reduce the possibility of divergent thinking, as it reduces the fluency, variety and the extent of originality of the possible ideas generated.[40]

Some depressive mood disorders might have a positive effect for creativity. Upon identifying several studies and analyzing data involving individuals with high levels of creativity, Christa Taylor was able to conclude that there is a clear positive relationship between creativity and depressive mood. A possible reason is that having a low mood could lead to new ways of perceiving and learning from the world, but it is unable to account for certain depressive disorders. The direct relationship between creativity and depression remains unclear, but the research conducted on this correlation has shed light that individuals who are struggling with a depressive disorder may be having even higher levels of creativity than a control group, and would be a close topic to monitor depending on the future trends of how creativity will be perceived and demanded.[41]

Theories

Schools of depression theories include:

- Cognitive theory of depression

- Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression

- Behavioral theories of depression

- Evolutionary approaches to depression

- Biology of depression

- Epigenetics of depression

Management

Depressed mood may not require professional treatment, and may be a normal temporary reaction to life events, a symptom of some medical condition, or a side effect of some drugs or medical treatments. A prolonged depressed mood, especially in combination with other symptoms, may lead to a diagnosis of a psychiatric or medical condition which may benefit from treatment. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2009 guidelines indicate that antidepressants should not be routinely used for the initial treatment of mild depression, because the risk-benefit ratio is poor.[42] Physical activity can have a protective effect against the emergence of depression.[43]

Physical activity can also decrease depressive symptoms due to the release of neurotrophic proteins in the brain that can help to rebuild the hippocampus that may be reduced due to depression.[44] Also yoga could be considered an ancillary treatment option for patients with depressive disorders and individuals with elevated levels of depression.[45][46]

Reminiscence of old and fond memories is another alternative form of treatment, especially for the elderly who have lived longer and have more experiences in life. It is a method that causes a person to recollect memories of their own life, leading to a process of self-recognition and identifying familiar stimuli. By maintaining one's personal past and identity, it is a technique that stimulates people to view their lives in a more objective and balanced way, causing them to pay attention to positive information in their life stories, which would successfully reduce depressive mood levels.[47]

Self-help books are a growing form of treatment for peoples physiological distress. There may be a possible connection between consumers of unguided self-help books and higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms. Researchers took many factors into consideration to find a difference in consumers and nonconsumers of self-help books. The study recruited 32 people between the ages of 18 and 65; 18 consumers and 14 nonconsumers, in both groups 75% of them were female. Then they broke the consumers into 11 who preferred problem-focused and 7 preferred growth-oriented. Those groups were tested for many things including cortisol levels, depressive symptomatology, and stress reactivity levels. There were no large differences between consumers of self-help books and nonconsumers when it comes to diurnal cortisol level, there was a large difference in depressive symptomatology with consumers having a higher mean score. The growth-oriented group has higher stress reactivity levels than the problem-focused group. However, the problem-focused group shows higher depressive symptomatology.[48]

A 2016 Cochrane review provided limited evidence that continuing antidepressant medication for one year seems to reduce the risk of depression recurrence with no additional harm.[49] However, a robust recommendation can not be drawn about psychological treatments or combination treatments in preventing recurrence.

There are empirical evidences of a connection between the type of stress management techniques and the level of daily depressive mood.[40]

Problem-focused coping leads to lower level of depression. Focusing on the problem allows for the subjects to view the situation in an objective way, evaluating the severity of the threat in an unbiased way, thus it lowers the probability of having depressive responses. On the other hand, emotion-focused coping promotes a depressed mood in stressful situations. The person has been contaminated with too much irrelevant information and loses focus on the options for resolving the problem. They fail to consider the potential consequences and choose the option that minimizes stress and maximizes well-being.

Epidemiology

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, the United Nations (UN) health agency reported, estimating that it affects more than 300 million people worldwide – the majority of them women, young people and the elderly. An estimated 4.4 percent of the global population suffers from depression, according to a report released by the UN World Health Organization (WHO), which shows an 18 percent increase in the number of people living with depression between 2005 and 2015.[50][51][52]

Depression is a major mental-health cause of disease burden. Its consequences further lead to significant burden in public health, including a higher risk of dementia, premature mortality arising from physical disorders, and maternal depression impacts on child growth and development.[53] Approximately 76% to 85% of depressed people in low- and middle-income countries do not receive treatment;[54] barriers to treatment include: inaccurate assessment, lack of trained health-care providers, social stigma and lack of resources.[55]

The stigma comes from misguided societal views that people with mental illness are different from everyone else, and they can choose to get better only if they wanted to.[56]Due to this more than half of the people with depression do not receive help with their disorders. The stigma leads to a strong preference for privacy.

The World Health Organization has constructed guidelines – known as The Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) – aiming to increase services for people with mental, neurological and substance-use disorders.[55] Depression is listed as one of conditions prioritized by the programme. Trials conducted show possibilities for the implementation of the programme in low-resource primary-care settings dependent on primary-care practitioners and lay health-workers.[57] Examples of mhGAP-endorsed therapies targeting depression include Group Interpersonal Therapy as group treatment for depression and "Thinking Health", which utilizes cognitive behavioral therapy to tackle perinatal depression.[55] Furthermore, effective screening in primary care is crucial for the access of treatments. The mhGAP adopted its approach of improving detection rates of depression by training general practitioners. However, there is still weak evidence supporting this training.[53]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2021) |

The Greco-Roman world used the tradition of the four humours to attempt to systematise sadness as "melancholia". This concept remained an important part of European and Islamic medicine until falling out of scientific favour in the 19th century.[58] Emil Kraepelin gave a noted scientific account of depression (German: das manisch-depressive Irresein) in his 1896 psychology encyclopedia "Psychiatrie".[59]

See also

References

- ↑ "Clinical risk of stigma and discrimination of mental illnesses: Need for objective assessment and quantification". Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55 (2): 178–82. April 2013. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.111459. PMID 23825855.

- ↑ "NIMH » Depression Basics". 2016. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/index.shtml.

- ↑ "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines". p. 30-1. https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/bluebook.pdf.

- ↑ "Empirical evidence for definitions of episode, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence in depression: a systematic review". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 28 (5): 544–562. October 2019. doi:10.1017/S2045796018000227. PMID 29769159.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Psychotherapy and counselling for depression (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. 2007. ISBN 978-1849203494. OCLC 436076587.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

- ↑ "The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans". Psychoneuroendocrinology 33 (6): 693–710. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. PMID 18602762.

- ↑ "Mothers' Differentiation and Depressive Symptoms among Adult Children". Journal of Marriage and the Family 72 (2): 333–345. April 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00703.x. PMID 20607119.

- ↑ "Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Public Health 59 (2): 359–72. April 2014. doi:10.1007/s00038-013-0519-5. PMID 24122075.

- ↑ "Mood, depression, and reproductive hormones in the menopausal transition". The American Journal of Medicine 118 (12B): 54–8. December 2005. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.033. PMID 16414327.

- ↑ "Life Events and Depression" (in en). Annals of Punjab Medical College 2 (1): 11–16. 2008-01-31. ISSN 2077-9143. http://apmcfmu.com/index.php/apmc/article/view/621.

- ↑ "Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA 314 (22): 2373–83. December 2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845. PMID 26647259.

- ↑ "NIMH » Perinatal Depression". https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/perinatal-depression/index.shtml.

- ↑ "Postpartum Depression". https://medlineplus.gov/postpartumdepression.html.

- ↑ "The emergence of depression in adolescence: development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 32 (1): 1–19. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016. PMID 17570526.

- ↑ "Depression" (in en). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- ↑ "Journal of Psychiatric Research | ScienceDirect.com by Elsevier" (in en-us). https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-psychiatric-research.

- ↑ "COVID-19 pandemic severely impacts mental health of young people" (in en). https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/03/210322112907.htm.

- ↑ "Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants". Psychological Medicine 46 (14): 2883–2906. October 2016. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001653. PMID 27523506. https://zenodo.org/record/895885.

- ↑ "Linking "big" personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin 136 (5): 768–821. September 2010. doi:10.1037/a0020327. PMID 20804236.

- ↑ "Signs and Symptoms of Mild, Moderate, and Severe Depression". 2017-03-27. https://www.healthline.com/health/depression/mild-depression.

- ↑ "Your Brain on Alcohol" (in en-GB). 2010. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/you-illuminated/201006/your-brain-alcohol.

- ↑ "Alcohol and mental health" (in en). https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/alcohol-facts/health-effects-of-alcohol/mental-health/alcohol-and-mental-health/.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "An examination of heavy drinking, depressed mood, drinking related constructs, and consequences among high-risk college students using a person-centered approach". Addictive Behaviors 78: 22–29. March 2018. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.022. PMID 29121529.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "How long does it last? Prior victimization from workplace bullying moderates the relationship between daily exposure to negative acts and subsequent depressed mood". European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 28 (2): 164–78. 2019-03-04. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2018.1564279.

- ↑ "General medical with depression drugs associated". Psychiatry 5 (12): 28–41. December 2008. PMID 19724774.

- ↑ Drug-Induced Diseases Section IV: Drug-Induced Psychiatric Diseases Chapter 18: Depression. pp. 1–23. https://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/Suicidality/DID-Chapter18.aspx. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition.. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- ↑ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH. (2012) Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. In: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 6th Edition. Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.) Butterworth Heinemann Script error: No such module "CS1 identifiers".

- ↑ "[Drawing up guidelines for the attendance of physical health of patients with severe mental illness]". L'Encephale 35 (4): 330–9. September 2009. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.10.014. PMID 19748369.

- ↑ "The relationship of depression and diabetes: pathophysiological and treatment implications". Psychoneuroendocrinology 36 (9): 1276–86. October 2011. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.03.005. PMID 21474250.

- ↑ "Evidence-based treatment of depression in patients with cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology 30 (11): 1187–96. April 2012. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7372. PMID 22412144.

- ↑ Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. 2 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 1296.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000a). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.. ISBN 978-0890420256.

- ↑ "Posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment". The American Journal of Medicine 119 (5): 383–90. May 2006. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.027. PMID 16651048.

- ↑ Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books. 2012. ISBN 978-0822352389.

- ↑ "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression: The Integrated Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (5): 427–49. September 2012. doi:10.1177/1745691612455204. PMID 26168502.

- ↑ "The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure". Journal of General Internal Medicine 16 (9): 606–13. September 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. PMID 11556941.

- ↑ "Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours". European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 23 (3): 342–63. 2014-05-04. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2012.744449. ISSN 1359-432X. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/53129/1/Bindl_Four-Quadrant%20Investigation_Accepted.pdf.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Idle minds are the devil's tools? Coping, depressed mood and divergent thinking in older adults". Aging & Mental Health 22 (12): 1606–1613. December 2018. doi:10.1080/13607863.2017.1387765. PMID 29052429.

- ↑ "Here's what the evidence shows about the links between creativity and depression" (in en). 2018. https://digest.bps.org.uk/2018/01/03/heres-what-the-evidence-shows-about-the-links-between-creativity-and-depression/.

- ↑ NICE guidelines, published October 2009. Nice.org.uk. Retrieved on 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". The American Journal of Psychiatry 175 (7): 631–648. July 2018. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. PMID 29690792. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/ws/files/94279645/Physical_activity_and_incident_SCHUCH_Publishedonline25April2018_GREEN_AAM.pdf.

- ↑ Publishing, H. H. (n.d.). Exercise is an all-natural treatment to fight depression. Retrieved November 7, 2019, from Harvard Health website: https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/exercise-is-an-all-natural-treatment-to-fight-depression

- ↑ "Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Depression and Anxiety 30 (11): 1068–83. November 2013. doi:10.1002/da.22166. PMID 23922209.

- ↑ "Effect of traditional yoga, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, on health related quality of life: a randomized controlled trial on patients on sick leave because of burnout". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 18 (1): 80. March 2018. doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2141-9. PMID 29510704.

- ↑ "A Follow-Up Study of a Reminiscence Intervention and Its Effects on Depressed Mood, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in the Elderly". The Journal of Psychology 151 (8): 789–803. November 2017. doi:10.1080/00223980.2017.1393379. PMID 29166223.

- ↑ "Salivary Cortisol Levels and Depressive Symptomatology in Consumers and Nonconsumers of Self-Help Books: A Pilot Study" (in en). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283723164.

- ↑ "Continuation and maintenance treatments for depression in older people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9: CD006727. September 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006727.pub3. PMID 27609183. PMC 6457610. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006727.pub3.

- ↑ "UN health agency reports depression now 'leading cause of disability worldwide'" (in en). 2017-02-23. https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/02/552062-un-health-agency-reports-depression-now-leading-cause-disability-worldwide.

- ↑ "Opinion | Our Great Depression" (in en-US). The New York Times. 2006-11-17. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/17/opinion/17solomon.html.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (2017-03-31). "Depression is leading cause of disability worldwide, says WHO study" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/31/depression-is-leading-cause-of-disability-worldwide-says-who-study.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Screening for depression: the global mental health context". World Psychiatry 16 (3): 316–317. October 2017. doi:10.1002/wps.20459. PMID 28941110.

- ↑ "Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys". Lancet 370 (9590): 841–50. September 2007. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61414-7. PMID 17826169.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "Depression" (in en). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- ↑ "Stigma and Discrimination". https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination.

- ↑ "The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lay counsellor-delivered psychological treatments for harmful and dependent drinking and moderate to severe depression in primary care in India: PREMIUM study protocol for randomized controlled trials". Trials 15 (1): 101. April 2014. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-101. PMID 24690184.

- ↑ (in fr). 1820. "Le mot mélancholie, consacré dans la langue vulgaire, pour exprimer l'état habituel de tristesse de quelques individus, doit etre laissé aux moralistes et aux poètes [...]." quoted in: "The historical vicissitudes of mental diseases: Their character and treatment". Historical Dimensions of Psychological Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1996 (published 2006). p. 217. ISBN 978-0521034760. https://books.google.com/books?id=6bBWOU_bgzsC. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ↑ "The historical vicissitudes of mental diseases: Their character and treatment". Historical Dimensions of Psychological Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1996 (published 2006). p. 218. ISBN 978-0521034760. https://books.google.com/books?id=6bBWOU_bgzsC. Retrieved 11 January 2021. "Depression as a distinct mental disease was formulated as such for the first time by Kraepelin [...] in the 5th edition (1896) of his Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch für Studi[e]rende und Aertze."

External links

| Classification |

|---|

|