Medicine:STAT3 GOF

| STAT3 GOF | |

|---|---|

| Other names | STAT3 Gain of Function [1] disease |

STAT3 GOF is a rare genetic disorder of the immune system. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a transcription factor which is encoded by the STAT3 gene in humans. Germline gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in the gene STAT3 causes this early-onset autoimmune disease characterized by lymphadenopathy, autoimmune cytopenias, multiorgan autoimmunity, infections, eczema, and short stature. Investigations conducted by Sarah E Flanagan and Mark Russell from the Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical School, Emma Haapaniemi from the Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical Schoolby, and Joshua Milner from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health have described this condition in 19 patients.[2][3][4]

Presentation

Clinically, the STAT3 GOF-associated phenotype is very diverse. It is characterized by prominent lymphoproliferation, including lymphadenopathy and/or hepatosplenomegaly, as well as early-onset multisystem autoimmunity. Hematologic autoimmunity is most prevalent including autoimmune hemolytic anemia, neutropenia, and/or thrombocytopenia. Others exhibited arthritis, lung disease consistent with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, hepatitis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia, and/or scleroderma. Several patients also have recurrent, severe infections and fungal infections with hypogammaglobulinemia. Postnatal short stature, with some exhibiting profound growth failure, is commonly seen. Early-onset type 1 diabetes was also noted in several of these patients.[2][3][4]

The stereotyped clinical phenotype of STAT3 GOF patients differs distinctly from that associated with germline STAT3 mutations shown to confer a loss-of-function (LOF). STAT3 loss-of-function mutations are responsible for hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, also called Job's syndrome, which is characterized by recurrent infections, unusual eczema-like skin rashes, and susceptibility to severe lung infections. While both LOF and GOF of STAT3 result in immune deficiency, GOF exhibit infections quite distinct from those observed with LOF, along with far more common connective tissue abnormalities.[2]

Furthermore, somatic gain-of-function STAT3 mutations are reported in association with solid and hematologic cancers. Therefore, one would have expected that germline STAT3 GOF mutations would have a similar increase the risk of cancer. However, only 1 patient presented with large granular lymphocytic leukemia and 1 parent with Hodgkin lymphoma.[2] The germline and somatic gain-of-function STAT3 mutations appear to result in distinctly different phenotypes.

Genetics

These gain-of-function mutations have been identified as germline mutations, meaning variations in the lineage of germ cells. Most mutations identified were de novo, meaning originating in the symptomatic patient and not inherited from either parent.[3][4] However, multiple cases of inheritance have also been identified. In 2 families, family members carrying a STAT3 mutation were asymptomatic or had a less severe phenotype, indicating that there are carriers of these mutations who display autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance.[2] Children of a parent who carries a STAT3 GOF mutation has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation. Within a family, each child’s risk of inheriting the mutated STAT3 gene is independent of whether other siblings have the mutation. In other words, if the first three children a family have the mutation, the fourth child has the same 50% risk of inheriting the mutation. Children who do not inherit the abnormal gene will not develop this syndrome or pass on the mutation.

Mechanism

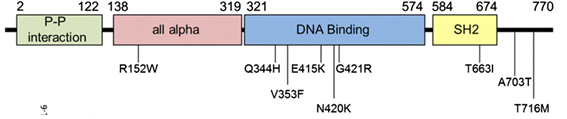

STAT3 GOF is caused by germline gain-of-function mutations in the gene STAT3. STAT3 maps to human chromosome 17q21.2, has 24 exons, and encodes for the 770 amino acid protein, STAT3.[5][6] STAT3 is part of a family of proteins known as the STAT protein. These proteins play an essential role in chemical signaling pathways within cells. STAT3 is a transcription factor that once activated, moves into the nucleus and binds to specific areas of DNA. By binding to regulatory regions near genes, STAT3 mediates the expression of a variety of genes and is therefore necessary for many cellular processes including cell proliferation, inflammation, differentiation, and survival.[7]

STAT3 GOF patients were found to have germline heterozygous variants. Various missense mutations have been identified in multiple domains of the protein, including the all-alpha, DNA-binding, SH2, and C-terminal transactivation domains (Milner et al, 2014). The genetic model for this disease is gain-of-function. This means that for people with STAT3 GOF disease, the gene STAT3 is hyperactive, leading to an intrinsic increase of transcriptional activity [2][4]

While the consequences of STAT3 hyperactivity are not yet fully understood, some insights into the underlying mechanisms have been identified. Researchers have identified an increase of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) in a large number of STAT GOF patients.[2] SOCS3 negatively regulates STAT3 and inhibits other STAT proteins like STAT5 and STAT1. STAT5 is important for regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation and function, which may explain why many STAT GOF patients have low Tregs. These Treg abnormalities likely play a major role in autoimmunity, although some patients with normal Tregs also presented with autoimmunity disorders.[2] Additionally, a partial decrease of STAT1 activation likely participates in immune deficiencies. Data suggest the upregulation of STAT3 transcriptional activity may have consequences for other cytokine signaling pathways as well.[2]

Notably, there has been no correlation between STAT3 hyperactivity and the severity of the phenotype, in addition to an absence of any genotype-phenotype correlation. This indicates that more research must be done to further understand the role that environmental or other genetic factors may play.[2][3][4]

Diagnosis

STAT3 GOF patients show moderate T-cell lymphopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and elevated double negative CD4/CD8 T cells (DNTs). More studies are required to understand the discrepancy associated with many laboratory manifestations, including an impaired Th17 differentiation among patients.[2][3][4]

Treatment

Once a diagnosis is made, the treatment is based on an individual’s clinical condition and may include standard management for autoimmunity. One patient with severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia responded well to rituximab. Blocking IL-6 activation with tocilizumab in one patient resulted in a dramatic improvement of arthritis.[2] Two patients exhibiting postnatal short stature were treated with growth hormone with good response. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT) is a possible treatment of this condition, but its effectiveness is unproven. Of the two patients treated by HCT, one patient died and the other was cured of autoimmune symptoms and improved growth.[2] Larger cohorts are required to further validate these therapeutic approaches. Investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the US National Institutes of Health currently have clinical protocols to study new approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder.[8]

References

- ↑ "STAT3 Gain of Function disease". https://www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/STAT3-Factsheet-508.pdf. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Milner, Joshua D.; Vogel, Tiphanie P.; Forbes, Lisa; Ma, Chi A.; Stray-Pedersen, Asbjørg; Niemela, Julie E.; Lyons, Jonathan J.; Engelhardt, Karin R. et al. (2015-01-22). "Early-onset lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity caused by germline STAT3 gain-of-function mutations". Blood 125 (4): 591–599. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-09-602763. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 25359994.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Haapaniemi, Emma M.; Kaustio, Meri; Rajala, Hanna L. M.; Adrichem, Arjan J. van; Kainulainen, Leena; Glumoff, Virpi; Doffinger, Rainer; Kuusanmäki, Heikki et al. (2015-01-22). "Autoimmunity, hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphoproliferation, and mycobacterial disease in patients with activating mutations in STAT3". Blood 125 (4): 639–648. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-570101. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 25349174.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Flanagan, Sarah E; Haapaniemi, Emma; Russell, Mark A; Caswell, Richard; Allen, Hana Lango; Franco, Elisa De; McDonald, Timothy J; Rajala, Hanna et al. (2014-01-01). "Activating germline mutations in STAT3 cause early-onset multi-organ autoimmune disease". Nature Genetics 46 (8): 812–814. doi:10.1038/ng.3040. PMID 25038750.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - * 102582 - SIGNAL TRANSDUCER AND ACTIVATOR OF TRANSCRIPTION 3; STAT3". http://www.omim.org/entry/102582. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ↑ Database, GeneCards Human Gene. "STAT3 Gene - GeneCards | STAT3 Protein | STAT3 Antibody". https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=STAT3. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ↑ Haddad, Elie (2015-01-22). "STAT3: too much may be worse than not enough!". Blood 125 (4): 583–584. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-610592. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 25614633.

- ↑ "Clinicaltrials.gov". https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home.

|