Medicine:Timeline of hepatitis

This is a Timeline of hepatitis, describing major events such as epidemics and medical developments, related to hepatitis A, B, C, D and E.

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 5th century BC | Hepatitis already plagues mankind.[1] |

| 17th-19th century | Jaundice epidemics break out in military and civilian populations during wars.[2] |

| 20th century | It is first recognized that viruses introduced by fecally contaminated food and water are responsible for hepatitis infection.[3] Multiple scientific developments from the second half of the century establish the current basis of knowledge and treatment of the H viruses. |

| 1960s–1970s | Several important milestones in the history of viral hepatitis happen in the 1960s.[4] The hepatitis c virus is identified. Blood tests to detect the hepatitis A and B infection are developed.[5] Modern viral hepatitis research begins with the discovery of Australia antigen.[4] |

| 1980s | Hepatitis B vaccine starts implementation worldwide.[6] |

| 1990s–2000s | The first Interferon alfa is approved for the treatment for hepatitis C.[7] Multiple drugs are developed for combating hepatitis. The World Hepatitis Alliance is founded.[7] |

| Recent years | There isn’t a vaccine for hepatitis C virus at this time.[8] About 375 million people are infected with the hepatitis B virus. HBV has killed more people than AIDS and is the cause of millions of cases of liver cancer.[9] Most cases of HB are found in the Asia-Pacific region.[6] In 2009, it was estimated that about 1.4 million cases of hepatitis A occurred worldwide.[10] Hepatitis E primarily occurs in South Asia and Africa.[3] |

Full timeline

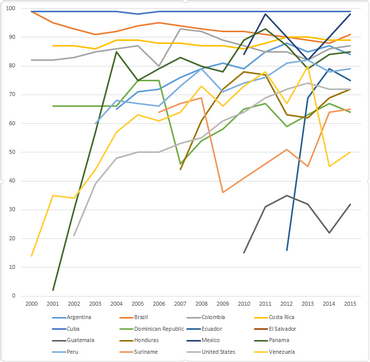

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in the Americas WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in countries from the African WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

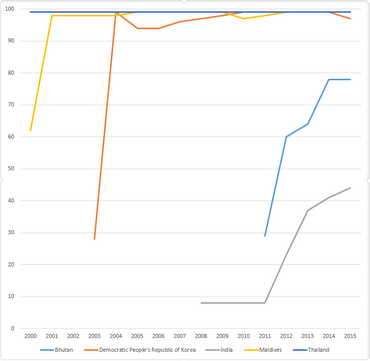

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in countries from South-East Asia WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

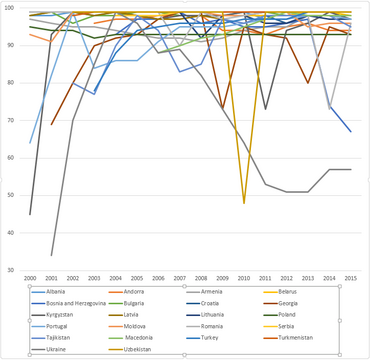

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in countries from the European WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in countries from the East-Mediterranean WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

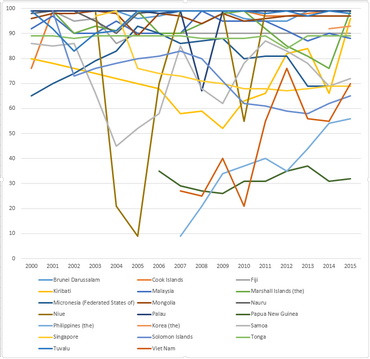

WHO-UNICEF estimates of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB-BD) coverage in countries from the Western Pacific WHO region in the years 2000-2015.[11]

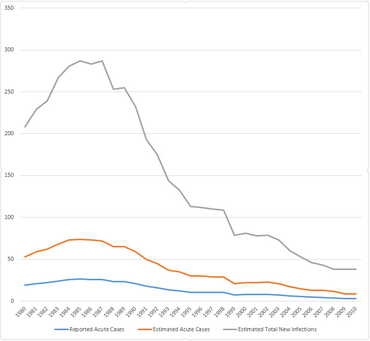

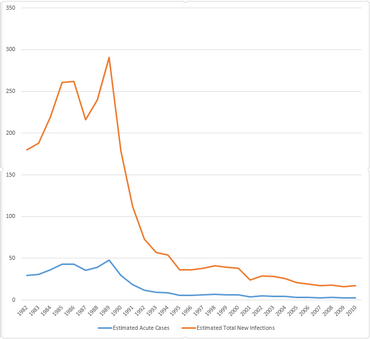

Incidence of Hepatitis A in the United States, in the years 1980-2010.[12]

Incidence of Hepatitis B in the United States, in the years 1980-2010.[12]

Incidence of Hepatitis C in the United States, in the years 1980-2011.[12]

Percentages of hepatitis A cases by occupation in Zhejiang Province, China. Cumulative.[13]

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 BC | Medical development | The earliest description of epidemic hepatitis, which may or may not have been due to hepatitis B virus, is credited to Greek physician Hippocrates, who describes a condition he called “epidemic jaundice”.[14][8] | Greece |

| 741–752 | Medical development | Pope Zachary quarantines individuals with jaundice to prevent its spread throughout Rome, suggesting an apparent infectious nature of this clinical finding.[4] | |

| 1861–1865 | Epidemic | Large hepatitis epidemic is documented during the American Civil War. 52,000 cases are estimated.[15][14] | United States |

| 1870 | Epidemic | Large hepatitis epidemic breaks out during the Franco–Prussian War.[14] | |

| 1865 | Scientific development | German physician Rudolf Virchow describes a patient with symptoms of epidemic jaundice in whom the lower end of the common bile duct was blocked with a plug of mucus. This would lead to the term “catarrhal jaundice,” because the disease is believed to be caused by catarrh as a result of mucus obstructing the bile duct.[4] | |

| 1885 | Scientific development | A. Lurman first describes an epidemic of serum hepatitis among 191 German ship workers in Bremen after a smallpox vaccination campaign using human lymph. It is the earliest record of an epidemic caused by hepatitis B virus.[6][14][4] | Germany |

| 1908 | Scientific development | S. McDonald publishes the hypothesis that the infectious jaundice is caused by a virus.[2][4] | |

| 1912 | Medical development | The name Hepatitis is first implemented.[3] | |

| 1914–1918 | Epidemic | Hepatitis epidemic breaks out during World War I.[14] | |

| 1942–1945 | Epidemic | Approximately 182,383 service members are hospitalized for Hepatitis C during World War II. The disease is contracted in two different ways. An epidemic of hepatitis breaks out among many service members who were vaccinated against yellow fever. The source of the infection is traced to the serum, or clear fluid in the blood, that is used in the vaccine. This form of the disease becomes known as serum hepatitis. A different form of hepatitis, acute hepatitis, is found among soldiers who have received blood transfusions.[8] | Europe |

| 1947 | Scientific development | MacCallum classifies viral hepatitis into two types. Viral hepatitis B is classified as serum hepatitis.[4] | |

| 1951 | Scientific development | Researchers describe a form of chronic hepatitis occurring primarily in young women. Because nearly 15% of these patients have positive lupus erithematosus cell tests, this disorder is first called lupoid hepatitis. By the 1970s its autoimmune origine would be discovered, and today the condition is referred as autoimmune hepatitis.[3] | |

| 1953 | Medical development | Hepatitis becomes a reportable disease.[3] | |

| 1957 | Scientific development | Scientists find that interferon could act as an antiviral drug. The name interferon is given since it could “interfere” with replication or multiplication of the virus.[5] | |

| 1963 | Scientific development | Blood test to detect hepatitis B infection is developed.[5] | |

| 1963–1965 | Scientific development | The hepatitis B virus surface antigen HBsAg (also known as Australia antigen) is first identified.[4][14] | |

| 1967 | Scientific development | American geneticist Baruch Samuel Blumberg and colleagues, while researching genetic links to disease susceptibility, discover the hepatitis B virus. In 1976, Dr. Blumberg would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery.[8][16] | |

| 1967 | Scientific development | Krugman and colleagues recognize the parenterally transmitted nature of hepatitis B, which would lead to the formulation of hygienic measures to prevent the disease.[14] | |

| 1968 | Scientific development | Prince, Murakami, and Okochi, through independent studies, confirm that the Australia antigen is found specifically in patients who had serum hepatitis (hepatitis B).[4] | |

| 1969 | Medical development | American physician Baruch Samuel Blumberg and colleagues develop the blood test that is used to detect the hepatitis B virus, and develop the first hepatitis B vaccine.[16] | |

| 1970 | Scientific development | DS Dane first describes the 42–47 nm double shelled particles (today called Dane particles) as the actual infectious particles, produced by the hepatitis B virus.[14][4] | |

| 1973 | Scientific development | American researchers Stephen Feinstone, Albert Kapikian and Robert Purcell, working at the National Institutes of Health, identify the virus responsible for hepatitis A. The virus is discovered in fecal samples from prisoner volunteers.[8] | United States |

| 1973 | Scientific development | Blood test to detect hepatitis A infection is developed.[5] | |

| 1975 | Scientific development | American and British researchers identify a type of hepatitis that doesn’t test positive for the proteins found with hepatitis A virus or hepatitis B virus. Both teams conclude that a previously unrecognized human hepatitis virus is the likely cause.[8] | |

| 1978 | Scientific development | Soviet scientist Mikhail Balayan, investigating an outbreak of non-A, non-B hepatitis in Tashkent, discovers the hepatitis E virus, by transmitting the disease into himself by oral administration of pooled stool extracts of 9 patients with non-A and non-B hepatitis.[17][18] | Uzbekistan |

| 1981 | Medical development | American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman develops the first effective vaccine for Hepatitis A virus.[8] | United States |

| 1982 | Medical development | Vaccine against hepatitis B becomes available. The vaccine is 95% effective in preventing infection and the development of chronic disease and liver cancer due to hepatitis B.[19] | |

| 1989 | Scientific development | The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Chiron Corporation working together identify the hepatitis C virus.[8] It is the first virus identified by a direct molecular approach.[15][7] | United States |

| 1990–1992 | Medical development | Screening the blood supply for hepatitis C virus begins in the United States . In 1992, a more sensitive test becomes available, thus eliminating the risk from known genotypes of HCV.[8] | United States |

| 1991 | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves Interferon alfa-2b (Intron A), for the treatment of hepatitis C virus.[8] | United States |

| 1991 | Policy | Egypt introduces childhood immunization against hepatitis B virus.[6] | Egypt |

| 1992 | Vaccination of infants against hepatitis B reaches coverage in 31 WHO Member States as part of their vaccination schedules.[19] | ||

| 1992 | Medical development | A blood test is developed to effectively screen blood before it is transfused. This would rediuce the risk of hepatitis C through a blood transfusion to approximately 0.01%.[5] | |

| 1992 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves lamivudine to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 1994 | Policy | Hepatitis B vaccine becomes part of the routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States.[20] | United States |

| 1995 | Medical development | Hepatitis A vaccine becomes available on the market.[13][21] | |

| 1996 | Epidemic | The Egyptian Ministry of Health estimates that 15 to 20 percent of Egyptians are infected with hepatitis c virus. Similar to the experience of many countries including Italy, the epidemic is linked to a nationwide vaccination campaign, during which needles were re-used. Egypt continues to report the highest hepatitis C rate in the world.[7] | Egypt |

| 1996 | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves alfa interferon (Roche- Roferon A) to treat hepatitis C.[5] | United States |

| 1997 | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves consensus interferon (Amgen-now InterMune-Infergen) to treat hepatitis C.[5] | United States |

| 1998 | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves combination of Interferon and anti-viral drug Ribavirin (Schering’s Intron A plus ribavirin) for hepatitis C virus therapy. The combination is most effective in preventing HCV relapse rather than as an anti-viral agent.[8][5] | United States |

| 2001 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves both pegylated interferon and the combination of pegylated interferon with ribavirin for hepatitis C virus therapy.[8][7] | United States |

| 2005 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves entecavir to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2006 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves telbivudine to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2006 | Medical development | Prison needle exchange programs are established or piloted in a number of countries around the world, including Switzerland , Germany , Spain , Moldova, the Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and Iran (NEP is based on the philosophy of harm reduction that attempts to reduce the risk factors for diseases such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.[7] | Switzerland , Germany , Spain , Moldova, the Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Iran |

| 2007 | Organization | The World Hepatitis Alliance is founded.[7] | |

| 2008 | Campaign | The World Hepatitis Alliance launches the first World Hepatitis Day on May 19, with a campaign called Am I Number 12?, referring to the statistic that, worldwide, one in every 12 people is living with a form of viral hepatitis.[7] | |

| 2010 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves rapid antibody test OraQuick for hepatitis C virus detection. This test gives results in 20 minutes.[8] | United States |

| 2010 | The Sixty-third World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization passes a viral hepatitis resolution, recognizing, among other points, “the need to reduce incidence to prevent and control viral hepatitis, to increase access to correct diagnosis and to provide appropriate treatment programmes in all regions. In the same year, the WHO endorses July 28th as World Hepatitis Day, making it the fourth official global health awareness day, alongside HIV, malaria and tuberculosis.”[7] | ||

| 2011 | Medical development | A recombinant hepatitis E vaccine is licensed in China, for use in people ages 16–65 years old.[20] | People's Republic of China |

| 2011 | Program launch | In response to the Resolution on Viral Hepatitis, the World Health Organization establishes a Global Hepatitis Program.[7] | |

| 2011 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves new oral agents boceprevir and telaprevir for the treatment of hepatitis C, in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. These new, triple-therapy regimens would cure rates as high as 70 to 75 percent. Therapy would last from 24 to 48 weeks.[22] | United States |

| 2012 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves tenofobir to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2013 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves sofosbuvir (sold under the brand name Sovaldi) and simeprevir (sold under the brand name Olysio) for the treatment for hepatitis C virus therapy.[8] | United States |

| 2014 | Vaccination of infants against hepatitis B reaches coverage in 184 WHO Member States as part of their vaccination schedules and 82% of children in these states receive the hepatitis B vaccine.[19] | ||

| 2015 | Publication | The World Health Organization launches its first Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons living with chronic hepatitis B infection. The recommendations:

| |

| 2015 | Scientific development | A Canadian paper describes using a mouse model of chronic hepatitis B infection and shows that interfering with certain proteins can facilitate clearance of the virus, which may have implications for human disease.[23] | Canada |

| 2016 | Medical development | The United States government recruits participants for the phase IV trial of the drug Hecolin, for the treatment of hepatitis E.[24] | United States |

See also

- Timeline of kidney cancer

- Timeline of cholera

- Timeline of global health

References

- ↑ "Viral Hepatitis B: Introduction". http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gastroenterology_hepatology/_pdfs/liver/viral_hepatitis_b.pdf. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The History of Hepatitis". https://web.stanford.edu/group/virus/1999/tchang/history.htm. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Moore, Elaine A. (2006-08-21). Hepatitis: Causes, Treatments and Resources. McFarland. p. 12. ISBN 9780786426232. https://archive.org/details/hepatitiscausest0000moor. Retrieved 28 February 2017. "hepatitis 20th century."

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Thomas, Emmanuel; Yoneda, Masato; Schiff, Eugene R. (2015). "Viral Hepatitis: Past and Future of HBV and HDV". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 5 (2): a021345. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021345. PMID 25646383.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Mandal, Ananya (2010-02-18). "Hepatitis C History". http://www.news-medical.net/health/Hepatitis-C-History.aspx. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Burns, Gregory S.; Thompson, Alexander J. (2014). "Viral Hepatitis B: Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 4 (12): a024935. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024935. PMID 25359547.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 "A brief history of hepatitis C: 1989 - 2016". http://www.catie.ca/en/practical-guides/hepc-in-depth/brief-history-hepc. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 York Morris, Susan (2016-02-03). "The History of Hepatitis C: A Timeline". http://www.healthline.com/health/hepatitis-c/hepatitis-c-history. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B: The Hunt for a Killer Virus". http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7248.html. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ MATHENY, SAMUEL C. (December 2012). "Hepatitis A". American Family Physician 86 (11): 1027–1034. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1201/p1027.html. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 "WHO-UNICEF estimates of HepB_BD coverage". WHO. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/timeseries/tswucoveragehepb_bd.html. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Historical reported cases and estimates". https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/incidencearchive.htm. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Wang, Zhifang; Yaping, Chen; Shuyun, Xie; Huakun, Lv (2016). "Changing Epidemiological Characteristics of Hepatitis A in Zhejiang Province, China: Increased Susceptibility in Adults". PLOS ONE 11 (4): e0153804. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153804. PMID 27093614. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1153804W.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 Datta, Sibnarayan; Chatterjee, Soumya; Veer, Vijay; Chakravarty, Runu (2012). "Molecular Biology of the Hepatitis B Virus for Clinicians". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology 2 (4): 353–365. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.10.003. PMID 25755457.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Christian Trepo (2014). "A brief history of hepatitis milestones". Liver International 34: 29–37. doi:10.1111/liv.12409. PMID 24373076.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Baruch Blumberg, MD, DPhil". http://www.hepb.org/about-us/baruch-blumberg-md-dphil/. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ↑ Khuroo, MS (2011). "Discovery of hepatitis E: the epidemic non-A, non-B hepatitis 30 years down the memory lane.". Virus Research 161 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.007. PMID 21320558.

- ↑ Arbeitskreis Blut, Untergruppe "Bewertung Blutassoziierter Krankheitserreger" (2009). "Hepatitis E Virus". Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy 36 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1159/000197321. PMID 21048820.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Hepatitis B fact sheet". http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B". http://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/hepatitis-and-hepatitis-b. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, Christopher B.; Nizet, Victor; Maldonado, Yvonne; Remington, Jack S.; Klein, Jerome O. (2014-12-24). Remington and Klein's Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn. ISBN 9780323340960. https://books.google.com/?id=W9b1BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA828&lpg=PA828&dq=%22hepatitis+a+vaccine%22+%22first+available+in%22#v=onepage&q=%22hepatitis%20a%20vaccine%22%20%22first%20available%20in%22&f=false. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C: A 21st Century Success Story (Op-Ed)". http://www.livescience.com/34606-hepatitis-treatment.html. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Ebert, Gregor; Preston, Simon; Allison, Cody; Cooney, James; Toe, Jesse G.; Stutz, Michael D.; Ojaimi, Samar; Scott, Hamish W. et al. (2015-05-05). "Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins prevent clearance of hepatitis B virus" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (18): 5797–5802. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502390112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 25902529. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.5797E.

- ↑ "Phase Ⅳ Clinical Trial of Recombinant Hepatitis E Vaccine(Hecolin®) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02189603. Retrieved 27 February 2017.