Medicine:XMEN disease

XMEN disease is a rare genetic disorder of the immune system that illustrates the role of glycosylation in the function of the immune system. XMEN stands for “X-linked MAGT1 deficiency with increased susceptibility to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection and N-linked glycosylation defect.[1]” The disease is characterized by CD4 lymphopenia, severe chronic viral infections, and defective T-lymphocyte activation. Investigators in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Lenardo, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health first described this condition in 2011.[2][3][4]

Presentation

XMEN patients have splenomegaly, chronic Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection, and are developmentally normal. They have an increased susceptibility for developing EBV+ lymphoma. Additionally, XMEN patients have excessive infections consistent with the underlying immunodeficiency. These infections included recurrent otitis media, sinusitis, viral pneumonia, diarrhea, upper respiratory infections, epiglottitis, and pertussis. Although autoimmune symptoms do not feature prominently in XMEN autoimmune cytopenias were observed in two unrelated patients.[2]

In the figure to the left, major features are present in all XMEN patients, while minor features are found only in some.

Genetics

XMEN disease is caused by loss of function mutations in the gene MAGT1.[2] MAGT1 is a 70 kb gene with 10 exons encoding for a 335 amino acid protein that maps to Xq21.1.[5] MagT1 is a component of the N-linked glycosylation machinery (oligosacchyrltransferase, OST), a fundamental component of all cells that regulates the attachment of sugar moieties onto specific sites in proteins. Many of the immunodeficiency-related features of XMEN disease are related to the hypoglycosylation phenotype caused by loss of the OST component MagT1.[6][7]

The conclusive connection between MAGT1, glycosylation, and Mg2+ import remains unknown. A prominent hypothesis from XMEN patients suggests that MAGT1's role in glycosylation is essential to the function (either directly or indirectly) of a Mg+2 transporter.[6][7]

MAGT1 is evolutionarily conserved and expressed in all mammalian cells with higher expression in hematopoietic lineages.[8] XMEN patients have been found to carry both MAGT1 deletions and missense mutations. However, the severity of the phenotype is not entirely explained by the genotype. The disease severity also likely depends on environmental and other genetic factors.[4]

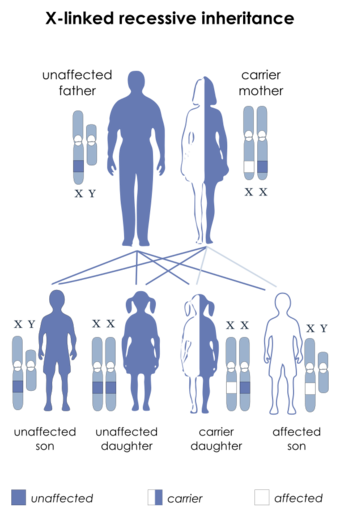

XMEN disease follows an X-linked inheritance pattern because the MAGT1 is located on the X chromosome. Mothers of XMEN patients exhibit preferential X chromosome inactivation of the chromosome with the mutation in their hematopoietic cells and are asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

XMEN patients generally have chronically high levels of EBV with increased EBV-infected cells, diminished thymic output of CD4+ cells, reduced CD4:CD8 ratio, moderately high B cell counts, and mild neutropenia. Their neutropenia may be related to their chronic EBV. Some patients also showed defective T cell proliferation in response to mitogen stimulation, variable immunoglobulin deficiencies, or deficient vaccination response.[2][3][4]

Treatment

Once a diagnosis is made, each individual's treatment is based on an individual's clinical condition. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant is a possible treatment of this condition but its effectiveness is unproven and may be accompanied by severe and potentially fatal hemorrhage.[9][10]

It was previously thought magnesium supplementation was a promising potential treatment for XMEN.[4] One of the consequences of loss of MAGT1 function is a decreased level of unbound intracellular Mg2+. This decrease leads to loss of expression of an immune cell receptor called NKG2D, which is involved in EBV-immunity. Mg2+ supplementation in some tests restored NKG2D expression and other functions that are abnormal in patients with XMEN disease. Early evidence suggested continuous oral magnesium threonate supplementation was safe and well tolerated.[3] A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study was conducted to evaluate the use of Mg2+ as a treatment for XMEN.[1] In vitro magnesium supplementation experiments failed to significantly rescue NKG2D expression in patients with XMEN disease and the clinical trial was stopped. Therefore, magnesium supplementation is unlikely to be an effective therapeutic option in XMEN disease.[1] Investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the US National Institutes of Health currently have clinical protocols to study new approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder.[11][12]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Chauvin, Samuel D.; Price, Susan; Zou, Juan; Hunsberger, Sally; Brofferio, Alessandra; Matthews, Helen; Similuk, Morgan; Rosenzweig, Sergio D. et al. (2021-10-16). "A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study of Magnesium Supplementation in Patients with XMEN Disease". Journal of Clinical Immunology 42 (1): 108–118. doi:10.1007/s10875-021-01137-w. ISSN 1573-2592. PMID 34655400.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Second messenger role for Mg2+ revealed by human T-cell immunodeficiency". Nature 475 (7357): 471–6. July 2011. doi:10.1038/nature10246. PMID 21796205.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Mg2+ regulates cytotoxic functions of NK and CD8 T cells in chronic EBV infection through NKG2D". Science 341 (6142): 186–91. July 2013. doi:10.1126/science.1240094. PMID 23846901. Bibcode: 2013Sci...341..186C.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "XMEN disease: a new primary immunodeficiency affecting Mg2+ regulation of immunity against Epstein-Barr virus". Blood 123 (14): 2148–52. April 2014. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-11-538686. PMID 24550228.

- ↑ "Identification and characterization of a novel mammalian Mg2+ transporter with channel-like properties". BMC Genomics 6 (48): 48. April 2005. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-6-48. PMID 15804357.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 "N-linked glycosylation and expression of immune-response genes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 294 (37): 13638–13656. September 2019. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.008903. PMID 31337704.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 "Defective glycosylation and multisystem abnormalities characterize the primary immunodeficiency XMEN disease". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 130 (1): 507–522. January 2020. doi:10.1172/JCI131116. PMID 31714901.

- ↑ "Mammalian MagT1 and TUSC3 are required for cellular magnesium uptake and vertebrate embryonic development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (37): 15750–5. September 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908332106. PMID 19717468. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10615750Z.

- ↑ Dimitrova, Dimana; Rose, Jeremy J.; Uzel, Gulbu; Cohen, Jeffrey I.; Rao, Koneti V.; Bleesing, Jacob H.; Kanakry, Christopher G.; Kanakry, Jennifer A. (January 2019). "Successful Bone Marrow Transplantation for XMEN: Hemorrhagic Risk Uncovered". Journal of Clinical Immunology 39 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1007/s10875-018-0573-0. ISSN 1573-2592. PMID 30470981. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30470981/.

- ↑ Ravell, Juan C.; Chauvin, Samuel D.; He, Tingyan; Lenardo, Michael (2020-07-01). "An Update on XMEN Disease" (in en). Journal of Clinical Immunology 40 (5): 671–681. doi:10.1007/s10875-020-00790-x. ISSN 1573-2592. PMID 32451662. PMC 7369250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-020-00790-x.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00001467 for "Genetic Analysis of Immune Disorders" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00246857 for "Screening Protocol for Genetic Diseases of Lymphocyte Homeostasis and Programmed Cell Death" at ClinicalTrials.gov

External links

|