Noise-predictive maximum-likelihood detection

Noise-Predictive Maximum-Likelihood (NPML) is a class of digital signal-processing methods suitable for magnetic data storage systems that operate at high linear recording densities. It is used for retrieval of data recorded on magnetic media. Data are read back by the read head, producing a weak and noisy analog signal. NPML aims at minimizing the influence of noise in the detection process. Successfully applied, it allows recording data at higher areal densities. Alternatives include peak detection, partial-response maximum-likelihood (PRML), and extended partial-response maximum likelihood (EPRML) detection.[1]

Although advances in head and media technologies historically have been the driving forces behind the increases in the areal recording density,[citation needed] digital signal processing and coding established themselves as cost-efficient techniques for enabling additional increases in areal density while preserving reliability.[1] Accordingly, the deployment of sophisticated detection schemes based on the concept of noise prediction are of paramount importance in the disk drive industry.

Principles

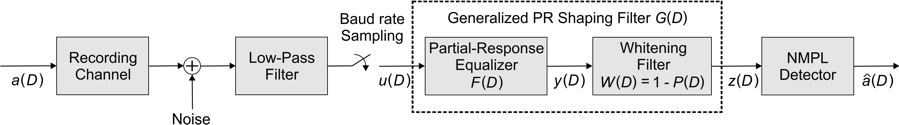

The NPML family of sequence-estimation data detectors arise by embedding a noise prediction/whitening process[2][3][4] into the branch metric computation of the Viterbi algorithm. The latter is a data detection technique for communication channels that exhibit intersymbol interference (ISI) with finite memory.

Reliable operation of the process is achieved by using hypothesized decisions associated with the branches of the trellis on which the Viterbi algorithm operates as well as tentative decisions corresponding to the path memory associated with each trellis state. NPML detectors can thus be viewed as reduced-state sequence-estimation detectors offering a range of implementation complexities. The complexity is governed by the number of detector states, which is equal to , , with denoting the maximum number of controlled ISI terms introduced by the combination of a partial-response shaping equalizer and the noise predictor. By judiciously choosing , practical NPML detectors can be devised that improve performance over PRML and EPRML detectors in terms of error rate and/or linear recording density.[2][3][4]

In the absence of noise enhancement or noise correlation, the PRML sequence detector performs maximum-likelihood sequence estimation. As the operating point moves to higher linear recording densities, optimality declines with linear partial-response (PR) equalization, which enhances noise and renders it correlated. A close match between the desired target polynomial and the physical channel can minimize losses. An effective way to achieve near optimal performance independently of the operating point—in terms of linear recording density—and the noise conditions is via noise prediction. In particular, the power of a stationary noise sequence , where the operator corresponds to a delay of one bit interval, at the output of a PR equalizer can be minimized by using an infinitely long predictor. A linear predictor with coefficients ,..., operating on the noise sequence produces the estimated noise sequence . Then, the prediction-error sequence given by

is white with minimum power. The optimum predictor

...

or the optimum noise-whitening filter

,

is the one that minimizes the prediction error sequence in a mean-square sense[2][3][4][5][6]

An infinitely long predictor filter would lead to a sequence detector structure that requires an unbounded number of states. Therefore, finite-length predictors that render the noise at the input of the sequence detector approximately white are of interest.

Generalized PR shaping polynomials of the form

,

where is a polynomial of order S and the noise-whitening filter has a finite order of , give rise to NPML systems when combined with sequence detection[2][3][4][5][6] In this case, the effective memory of the system is limited to

,

requiring a -state NPML detector if no reduced-state detection is employed.

As an example, if

then this corresponds to the classical PR4 signal shaping. Using a whitening filter , the generalized PR target becomes

,

and the effective ISI memory of the system is limited to

symbols. In this case, the full-state NMPL detector performs maximum likelihood sequence estimation (MLSE) using the -state trellis corresponding to .

The NPML detector is efficiently implemented via the Viterbi algorithm, which recursively computes the estimated data sequence.[2][3][4][5][6]

where denotes the binary sequence of recorded data bits and z(D) the signal sequence at the output of the noise whitening filter .

Reduced-state sequence-detection schemes[7][8][9] have been studied for application in the magnetic-recording channel[2][4] and the references therein. For example, the NPML detectors with generalized PR target polynomials

can be viewed as a family of reduced-state detectors with embedded feedback. These detectors exist in a form in which the decision-feedback path can be realized by simple table look-up operations, whereby the contents of these tables can be updated as a function of the operating conditions.[2] Analytical and experimental studies have shown that a judicious tradeoff between performance and state complexity leads to practical schemes with considerable performance gains. Thus, reduced-state approaches are promising for increasing linear density.

Depending on the surface roughness and particle size, particulate media might exhibit nonstationary data-dependent transition or medium noise rather than colored stationary medium noise. Improvements o\in the quality of the readback head as well as the incorporation of low-noise preamplifiers may render the data-dependent medium noise a significant component of the total noise affecting performance. Because medium noise is correlated and data-dependent, information about noise and data patterns in past samples can provide information about noise in other samples. Thus, the concept of noise prediction for stationary Gaussian noise sources developed in [2][6] can be naturally extended to the case where noise characteristics depend highly on local data patterns.[1][10][11][12]

By modeling the data-dependent noise as a finite-order Markov process, the optimum MLSE for channels with ISI has been derived.[11] In particular, it when the data-dependent noise is conditionally Gauss–Markov, the branch metrics can be computed from the conditional second-order statistics of the noise process. In other words, the optimum MLSE can be implemented efficiently by using the Viterbi algorithm, in which the branch-metric computation involves data-dependent noise prediction.[11] Because the predictor coefficients and prediction error both depend on the local data pattern, the resulting structure has been called a data-dependent NPML detector.[1][12][10] Reduced-state sequence detection schemes can be applied to data-dependent NPML, reducing implementation complexity.

NPML and its various forms represent the core read-channel and detection technology used in recording systems employing advanced error-correcting codes that lend themselves to soft decoding, such as low-density parity check (LDPC) codes. For example, if noise-predictive detection is performed in conjunction with a maximum a posteriori (MAP) detection algorithm such as the BCJR algorithm[13] then NPML and NPML-like detection allow the computation of soft reliability information on individual code symbols, while retaining all the performance advantages associated with noise-predictive techniques. The soft information generated in this manner is used for soft decoding of the error-correcting code. Moreover, the soft information computed by the decoder can be fed back again to the soft detector to improve detection performance. In this way it is possible to iteratively improve the error-rate performance at the decoder output in successive soft detection/decoding rounds.

History

Beginning in the 1980s several digital signal-processing and coding techniques were introduced into disk drives to improve the drive error-rate performance for operation at higher areal densities and for reducing manufacturing and servicing costs. In the early 1990s, partial-response class-4[14][15][16] (PR4) signal shaping in conjunction with maximum-likelihood sequence detection, eventually known as PRML technique[14][15][16] replaced the peak detection systems that used run-length-limited (RLL) (d,k)-constrained coding. This development paved the way for future applications of advanced coding and signal-processing techniques[1] in magnetic data storage.

NPML detection was first described in 1996[4][17] and eventually found wide application in HDD read channel design. The “noise predictive” concept was later extended to handle autoregressive (AR) noise processes and autoregressive moving-average (ARMA) stationary noise processes[2] The concept was extended to include a variety of non-stationary noise sources, such as head, transition jitter and media noise;[10][11][12] it was applied to various post-processing schemes.[18][19][20] Noise prediction became an integral part of the metric computation in a wide variety of iterative detection/decoding schemes.

The pioneering research work on partial-response maximum-likelihood (PRML) and noise-predictive maximum-likelihood (NPML) detection and its impact on the industry were recognized in 2005[21] by the European Eduard Rhein Foundation Technology Award.[22]

Applications

NPML technology were first introduced into IBM's line of HDD products in the late 1990s.[23] Eventually, noise-predictive detection became a de facto standard and in its various instantiations became the core technology of the read channel module in HDD systems.[24][25]

In 2010, NPML was introduced into IBM's Linear Tape Open (LTO) tape drive products and in 2011 in IBM's enterprise-class tape drives.[citation needed]

See also

- Maximum likelihood

- Partial-response maximum-likelihood

- Viterbi algorithm

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Eleftheriou, E. (2003). John G., Proakis. ed. "Signal Processing for Magnetic-Recording Channels". Wiley Encyclopedia of Telecommunications (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 4: 2247–2268.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Coker, J. D.; E. Eleftheriou; R. L. Galbraith; W. Hirt (1998). "Noise-Predictive Maximum Likelihood (NPML) Detection". IEEE Trans. Magn. 34 (1): 110–117. doi:10.1109/20.663468. Bibcode: 1998ITM....34..110C.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Eleftheriou, E; W. Hirt (1996). "Improving Performance of PRML/EPRML through Noise Prediction". IEEE Trans. Magn. 32 part 1 (5): 3968–3970. doi:10.1109/20.539233. Bibcode: 1996ITM....32.3968E.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Eleftheriou, E.; W. Hirt (1996). "Noise-Predictive Maximum-Likelihood (NPML) Detection for the Magnetic Recording Channel". Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Commun.: 556–560.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Eleftheriou, E.; S. Ölçer; R. A. Hutchins (2010). "Adaptive Noise-Predictive Maximum-Likelihood (NPML) Data Detection for Magnetic Tape Storage Systems". IBM J. Res. Dev. 54 (2, paper 7): 7:1. doi:10.1147/JRD.2010.2041034.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Chevillat, P.R.; E. Eleftheriou; D. Maiwald (1992). "Noise Predictive Partial-Response Equalizers and Applications". Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Commun.: 942–947.

- ↑ Eyuboglu, V. M.; S. U. Qureshi (1998). "Reduced-state Sequence Estimation with Set Partitioning and Decision Feedback". IEEE Trans. Commun. 36: 13–20. doi:10.1109/26.2724. Bibcode: 1988ITCom..36...13E.

- ↑ Duell-Hallen, A.; C. Heegard (1989). "Delayed Decision-feedback Sequence Estimation". IEEE Trans. Commun. 37 (5): 428–436. doi:10.1109/26.24594. Bibcode: 1989ITCom..37..428D.

- ↑ Chevillat, P. R.; E. Eleftheriou (1989). "Decoding of Trellis-encoded Signals in the Presence of Intersymbol Interference and Noise". IEEE Trans. Commun. 37 (7): 669–676. doi:10.1109/26.31158.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Caroselli, J.; S. A. Altekar; P. McEwen; J. K. Wolf (1997). "Improved Detection for Magnetic Recording Systems with Media Noise". IEEE Trans. Magn. 33 (5): 2779–2781. doi:10.1109/20.617728. Bibcode: 1997ITM....33.2779C.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Kavcic, A.; J. M. F. Moura (2000). "The Viterbi Algorithm and Markov Noise Memory". IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 46: 291–301. doi:10.1109/18.817531.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Moon, J.; J. Park (2001). "Pattern-Dependent Noise Prediction in Signal-Dependent Noise". IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 19 (4): 730–743. doi:10.1109/49.920181.

- ↑ Bahl, L. R.; J. Cocke; F. Jelinek; J. Raviv (1974). "Optimal Decoding of Linear Codes for Minimizing Symbol Error Rate". IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 20 (2): 284–287. doi:10.1109/TIT.1974.1055186.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kobayashi, H.; D. T. Tang (1970). "Application of Partial-Response Channel Coding to Magnetic Recording Systems". IBM J. Res. Dev. 14 (4): 368–375. doi:10.1147/rd.144.0368.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kobayashi, H. (1971). "Application of Probabilistic Decoding to Digital Magnetic Recording". IBM J. Res. Dev. 15: 65–74. doi:10.1147/rd.151.0064.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Cideciyan, R. D.; F. Dolivo; R. Hermann; W. Hirt; W. Schott (1992). "A PRML System for Digital Magnetic Recording". IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 10: 38–56. doi:10.1109/49.124468.

- ↑ Eleftheriou, E.; W. Hirt (1996). "Improving Performance of PRML/EPRML through Noise Prediction". IEEE Trans. Magn. 32 part 1 (5): 3968–3970. doi:10.1109/20.539233. Bibcode: 1996ITM....32.3968E.

- ↑ Sonntag, J. L.; B. Vasic (2000). "Implementation and Bench Characterization of a Read Channel with Parity Check Postprocessor". Digest of the Magnetic Recording Conf. (TMRC).

- ↑ Cideciyan, R. D.; J. D. Coker; E. Eleftheriou; R. L. Galbraith (2001). "NPML Detection Combined with Parity-Based Postprocessing". IEEE Trans. Magn. 37 (2): 714–720. doi:10.1109/20.917606. Bibcode: 2001ITM....37..714C.

- ↑ Feng, W.; A. Vityaev; G. Burd; N. Nazari (2000). "On the performance of parity codes in magnetic recording systems". Globecom '00 - IEEE. Global Telecommunications Conference. Conference Record (Cat. No.00CH37137). 3. 1877–1881. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.2000.891959. ISBN 978-0-7803-6451-6.

- ↑ "Technologiepreis 2005". http://www.eduard-rhein-stiftung.de/html/2005/T2005_e.html.

- ↑ "Eduard Rhein Stiftung". http://www.eduard-rhein-stiftung.de/.

- ↑ Popovich, Ken. "Hitachi to Buy IBM's Hard Drive Business". PC Magazine. https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,5915,00.asp. Retrieved June 5, 2002.

- ↑ Yoo, Daniel. "Marvell Contributes to Read-Rite's Areal Density Record". Marvell. http://www.marvell.com/company/news/pressDetail.do?releaseID=192.

- ↑ "Samsung SV0802N hard drive specifications". http://www.testhdd.com/SpinPoint-V80-SV0802N-hard-drive-80-GB-ATA-133-5225.html.

|