Philosophy:Invagination

In developmental biology, invagination is a mechanism that takes place during gastrulation. This mechanism or cell movement happens mostly in the vegetal pole. Invagination consists of the folding of an area of the exterior sheet of cells towards the inside of the blastula. In each organism, the complexity will be different depending on the number of cells. Invagination can be referenced as one of the steps of the establishment of the body plan.[1][2]The term, originally used in embryology, has been adopted in other disciplines as well. There is more than one type of movement for invagination. Two common types are axial and orthogonal. The difference between the production of the tube formed in the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix. Axial can be formed at a single point along the axis of a surface. Orthogonal is linear and trough. [3]

Biology

- Invagination is the morphogenetic processes by which an embryo takes form, and is the initial step of gastrulation,[4] the massive reorganization of the embryo from a simple spherical ball of cells, the blastula, into a multi-layered organism, with differentiated germ layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. More localized invaginations also occur later in embryonic development,

- The inner membrane of a mitochondrion invaginates to form cristae, thus providing a much greater surface area to accommodate the protein complexes and other participants that produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP).[5]

- Invagination occurs during endocytosis and exocytosis when a vesicle forms within the cell and the membrane closes around it.

- Invagination of a part of the intestine into another part is called intussusception.[6]

Amphioxus

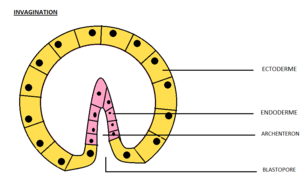

The invagination in Amphioxus is the first cell movement of gastrulation. This process was first described by Conklin. During gastrulation, the blastula will be transformed by the invagination. The endoderm will fold towards the inner part and that way the blastocoel will be gone transforming into like a cup-shaped structure with a double wall. The inner wall will be called the archenteron; the primitive gut. The archenteron will open to the exterior through the blastopore. The outer wall will become the ectoderm. Later forming the epidermis and neural crest.[7]

Tunicates

In tunicates, invagination is the first mechanism that takes place during gastrulation. The four largest endoderm cells induce the invagination process in the tunicates. Invagination consists of the internal movements of a sheet of cells (the endoderm) based on changes in their shape. The blastula of the tunicates is a little flattened in the vegetal pole making a change of shape from a columnar to a wedge shape. Once the endoderm cells were invaginated, the cells will keep moving beneath the ectoderm. Later, the blastopore will be formed and with this, the invagination process is complete. The blastopore will be surrounded by the mesoderm by all sides.[8]

Philosophy

In Continental philosophy, the term invagination is used to explain a special kind of metanarrative. It was first used by Maurice Merleau-Ponty[9] (French: invagination) to describe the dynamic self-differentiation of the 'flesh'. It was later used by Rosalind E. Krauss and Jacques Derrida ("The Law of Genre", Glyph 7, 1980); for Derrida, an invaginated text is a narrative that folds upon itself, "endlessly swapping outside for inside and thereby producing a structure en abyme".[10] He applies the term to such texts as Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgment[10] and Maurice Blanchot's La Folie du Jour.[11] Invagination is an aspect of différance, since according to Derrida it opens the "inside" to the "other" and denies both inside and outside a stable identity.[12]

References

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott; Rauno, Anne (1997) (in english) (book). Embryology, Constructing the Organism. Sunderland, MA.: Sinauer Associates Inc.. ISBN 0-87893-237-2.

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott; Barresi, Michael (2016) (in English) (book). Developmental Biology. Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates Inc.. ISBN 9781605354705.

- ↑ Jamie A. Davies, In Mechanisms of Morphogensis (Second Edition), 2013

- ↑ Alberts (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Science.

- ↑ Cronk, Jeff. "Biochemistry Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. https://web.archive.org/web/20121114235521/http://guweb2.gonzaga.edu/faculty/cronk/biochem/M-index.cfm?definition=mitochondria.[dead link]

- ↑ Blanco, Felix. "Intussusception". http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/930708-overview. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Browder, Leon (1984). Developmental Biology. Canada: CBS College Publishing. p. 599. ISBN 4833702010.

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott; Rauno, Anne (1997) (in english) (book). Embryology, Constructing the Organism. Sunderland, MA.: Sinauer Associates Inc.. ISBN 0-87893-237-2.

- ↑ Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1968). The Visible and the Invisible. Boston, MA: Northwestern University Press. p. 152. ISBN 0810104571.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chaplin, Susan (2004). Law, Sensibility, and the Sublime in Eighteenth-Century Women's Fiction: Speaking of Dread. Ashgate. p. 23. ISBN 9780754633068. https://books.google.com/books?id=zOqNqq4i2ioC&pg=PA23. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Jones, Amelia (2003). The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. Psychology Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780415267069. https://books.google.com/books?id=E5zCts8ax58C&pg=PA200. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Wortham, Simon Morgan (2010). The Derrida Dictionary. Continuum International. p. 76. ISBN 9781847065261. https://books.google.com/books?id=PVtjXOyPSMAC&pg=PA76. Retrieved 12 January 2013.