Philosophy:Vihara

Vihara (Sanskrit: vihāra) generally refers to a monastery for Buddhist renunciates. The concept is ancient and in early Sanskrit and Pali texts, it meant any arrangement of space or facilities for pleasure and entertainment.[2][3] The term evolved into an architectural concept wherein it refers to living quarters for monks with an open shared space or courtyard, particularly in Buddhism. The term is also found in Ajivika, Hindu and Jain monastic literature, usually referring to temporary refuge for wandering monks or nuns during the annual Indian monsoons.[2][4][5] In modern Jainism, the monks continue to wander from town to town except during the rainy season (Chaturmas), the term "vihara" refers their wanderings.[6][7]

Vihara or vihara hall has a more specific meaning in the architecture of India, especially ancient Indian rock-cut architecture. Here it means a central hall, with small cells connected to it sometimes with beds carved from the stone. Some have a shrine cell set back at the centre of the back wall, containing a stupa in early examples, or a Buddha statue later. Typical large sites such as the Ajanta Caves, Aurangabad Caves, Karli Caves, and Kanheri Caves contain several viharas. Some included a chaitya or worship hall nearby.[8] The vihara was originated to be a shelter for Monks when it rains.

Etymology and nomenclature

Vihāra is a Sanskrit word that appears in several Vedic texts with context sensitive meanings. It generally means a form of "distribution, transposition, separation, arrangement", either of words or sacred fires or sacrificial ground. Alternatively, it refers to a form of wandering roaming, any place to rest or please oneself or enjoy one's pastime in, a meaning more common in late Vedic texts, the Epics and Gryhasutra literature.[2][9][10]

Its meaning in post-Vedic era is more specifically a form of rest house or temple or monastery in ascetic traditions of India, particularly for a group of monks.[2] It particularly referred to a hall that were used as temples or where monks met and some walked about.[2][11] In performance arts context, the term means the theatre, playhouse, convent or temple compound to meet, perform or relax in. Later it referred to a form of temple or monastery construction in Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism, wherein the design has a central hall and attached separated shrines for residence either for monks or for gods, goddesses and some sacred figure such as Tirthankaras or the Buddha or a Guru. The word means a Jain or Hindu temple or "dwelling, waiting place" in many medieval era inscriptions and texts, from vi-har which means "to construct".[4][5]

It contrasts with Aranya (Sanskrit) or Aranna (Pali) which means "forest".[11][10] In medieval era, the term meant any monastery, particularly for Buddhist monks.[11][12] Matha is another term for monastery in Indian religious tradition,[13] today normally used for Hindu establishments.

The northern India n state of Bihar derives its name from the word "vihara", due to the abundance of Buddhist monasteries in that area. The word "vihara" has also been borrowed in Malay where it is spelled "biara," and denotes a monastery or other non-Muslim place of worship. In Thailand and China (called jingshe; Chinese: 精舎), "vihara" has a narrower meaning, and designates a shrine hall or retreat house. It is called a "Wihan" (วิหาร) in Thai, and a "Vihear" in Khmer. In Burmese, wihara (ဝိဟာရ, IPA: [wḭhəɹa̰]), means "monastery," but the native Burmese word kyaung (ကျောင်း, IPA: [tɕáʊɴ]) is preferred. Monks wandering from place to place preaching and seeking alms often stayed together in the sangha.[citation needed] In the Punjabi language, an open space inside a home is called a 'vehra'.

Origins

Viharas as pleasure centers

During the 3rd-century BCE era of Ashoka, vihara yatras were travels aimed at enjoyments, pleasures and hobbies such as hunting. These contrasted with dharma yatras which related to religious pursuits and pilgrimage.[3] After Ashoka converted to Buddhism, states Lahiri, he started dharma yatras around mid 3rd century BCE instead of hedonistic royal vihara yatras.[3]

Viharas as monasteries

The early history of viharas is unclear. Monasteries in the form of caves are dated to centuries before the start of the common era, for Ajivikas, Buddhists and Jainas. The rock-cut architecture found in cave viharas from the 2nd-century BCE have roots in the Maurya Empire period.[14] In and around the Bihar state of India are a group of residential cave monuments all dated to be from pre-common era, reflecting the Maurya architecture. Some of these have Brahmi script inscription which confirms their antiquity, but the inscriptions were likely added to pre-existing caves.[14] The oldest layer of Buddhist and Jain texts mention legends of the Buddha, the Jain Tirthankaras or sramana monks living in caves.[14][15][16] If these records derived from an oral tradition accurately reflect the significance of monks and caves in the times of the Buddha and the Mahavira, then cave residence tradition dates back to at least the 5th century BCE. According to Allchin and Erdosy, the legend of First Buddhist Council is dated to a period just after the death of the Buddha. It mentions monks gathering at a cave near Rajgiri, and this dates it in pre-Mauryan times.[14] However, the square courtyard with cells architecture of vihara, state Allchin and Erdosy, is dated to the Mauryan period. The earlier monastic residences of Ajivikas, Buddhists, Hindus, and Jains were likely outside rock cliffs and made of temporary materials and these have not survived.[17]

The earliest known gift of immovable property for monastic purposes ever recorded in an Indian inscription is credited to Emperor Ashoka, and it is a donation to the Ajivikas.[18] According to Johannes Bronkhorst, this created competitive financial pressures on all traditions, including the Hindu Brahmins. This may have led to the development of viharas as shelters for monks, and evolution in the Ashrama concept to agraharas or Hindu monasteries. These shelters were normally accompanied by donation of revenue from villages nearby, who would work and support these cave residences with food and services. The Karle inscription dated to the 1st century CE donates a cave and nearby village, states Bronkhorst, "for the support of the ascetics living in the caves at Valuraka [Karle] without any distinction of sect or origin". Buddhist texts from Bengal, dated to centuries later, use the term asrama-vihara or agrahara-vihara for their monasteries.[18]

Buddhist viharas or monasteries may be described as a residence for monks, a centre for religious work and meditation and a centre of Buddhist learning. Reference to five kinds of dwellings (Pancha Lenani) namely, Vihara, Addayoga, Pasada, Hammiya and Guha is found in the Buddhist canonical texts as fit for monks. Of these only the Vihara (monastery) and Guha (Cave) have survived.

At some stage of Buddhism, like other Indian religious traditions, the wandering monks of the Sangha dedicated to asceticism and the monastic life, wandered from place to place. During the rainy season (cf. vassa) they stayed in temporary shelters. In Buddhist theology relating to rebirth and merit earning, it was considered an act of merit not only to feed a monk but also to shelter him, sumptuous monasteries were created by rich lay devotees.

Architecture

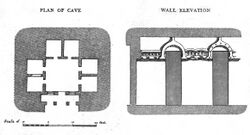

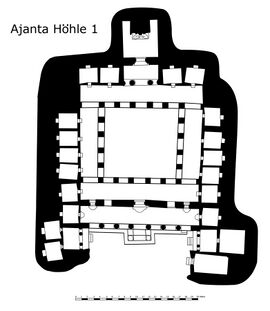

The only substantial remains of very early viharas are in the rock-cut complexes, mostly in north India, the Deccan in particular, but this is an accident of survival. Originally structural viharas of stone or brick would probably have been at least as common everywhere, and the norm in the south. By the second century BCE a standard plan for a vihara was established; these form the majority of Buddhist rock-cut "caves". It consisted of a roughly square rectangular hall, in rock-cut cases, or probably an open court in structural examples, off which there were a number of small cells. Rock-cut cells are often fitted with rock-cut platforms for beds and pillows. The front wall had one or more entrances, and often a verandah. Later the back wall facing the entrance had a fairly small shrine-room, often reached through an ante-chamber. Initially these held stupas, but later a large sculpted Buddha image, sometimes with reliefs on the walls. The verandah might also have sculpture, and in some cases the walls of the main hall. Paintings were perhaps more common, but these rarely survive, except in a few cases such as Caves 2, 10, 11 and 17 at the Ajanta Caves. As later rock-cut viharas are often on up to three storeys, this was also probably the case with the structural ones.[19]

As the vihara acquired a central image, it came to take over the function of the chaitya worship hall, and eventually these ceased to be built. This was despite the rock-cut vihara shrine room usually offering no path for circumambulation or pradakshina, an important ritual practice.[20]

In early medieval era, Viharas became important institutions and a part of Buddhist Universities with thousands of students, such as Nalanda. Life in "Viharas" was codified early on. It is the object of a part of the Pali canon, the Vinaya Pitaka or "basket of monastic discipline". Shalban Vihara in Bangladesh is an example of a structural monastery with 115 cells, where the lower parts of the brick-built structure have been excavated. Somapura Mahavihara, also in Bangladesh, was a larger vihara, mostly 8th-century, with 177 cells around a huge central temple.[citation needed]

Variants in rock-cut viharas

Usually the standard form as described above is followed, but there are some variants. Two vihara halls, Cave 5 at Ellora and Cave 11 at Kanheri, have very low platforms running most of the length of the main hall. These were probably used as some combination of benches or tables for dining, desks for study, and possibly beds. They are often termed "dining-hall" or the "Durbar Hall" at Kanheri, on no good evidence.[21]

Cave 11 at the Bedse Caves is a fairly small 1st-century vihara, with nine cells in the interior and originally four around the entrance, and no shrine room. It is distinguished by elaborate gavaksha and railing relief carving around the cell-doors, but especially by having a rounded roof and apsidal far end, like a chaitya hall.[22]

History

The earliest Buddhist rock-cut cave abodes and sacred places are found in the western Deccan dating back to the 3rd century BC.[23] These earliest rock-cut caves include the Bhaja Caves, the Karla Caves, and some of the Ajanta Caves.

Vihara with central shrine containing devotional images of the Buddha, dated to about the 2nd century CE are found in the northwestern area of Gandhara, in sites such as Jaulian, Kalawan (in the Taxila area) or Dharmarajika, which states Behrendt, possibly were the prototypes for the 4th century monasteries such as those at Devnimori in Gujarat.[24] This is supported by the discovery of clay and bronze Buddha statues, but it is unclear if the statue is of a later date.[24] According to Behrendt, these "must have been the architectural prototype for the later northern and western Buddhist shrines in the Ajanta Caves, Aurangabad, Ellora, Nalanda, Ratnagiri and other sites".[24] Behrendt's proposal follows the model that states the northwestern influences and Kushana era during the 1st and 2nd century CE triggered the development of Buddhist art and monastery designs. In contrast, Susan Huntington states that this late nineteenth and early twentieth century model is increasingly questioned by the discovery of pre-Kushana era Buddha images outside the northwestern territories. Further, states Huntington, "archaeological, literary, and inscriptional evidence" such as those in Madhya Pradesh cast further doubts.[25] Devotional worship of Buddha is traceable, for example, to Bharhut Buddhist monuments dated between 2nd and 1st century BCE.[25] The Krishna or Kanha Cave (Cave 19) at Nasik has the central hall with connected cells, and it is generally dated to about the 1st century BCE.[26][27]

The early stone viharas mimicked the timber construction that likely preceded them.[28]

Inscriptional evidence on stone and copper plates indicate that Buddhist viharas were often co-built with Hindu and Jain temples. The Gupta Empire era witnessed the building of numerous viharas, including those at the Ajanta Caves.[29] Some of these viharas and temples though evidenced in texts and inscriptions are no longer physically found, likely destroyed in later centuries by natural causes or due to war.[29]

Viharas as a source of major Buddhist traditions

As more people joined Buddhist monastic sangha, the senior monks adopted a code of discipline which came to be known in the Pali Canon as the Vinaya texts.[30] These texts are mostly concerned with the rules of the sangha. The rules are preceded by stories telling how the Buddha came to lay them down, and followed by explanations and analysis. According to the stories, the rules were devised on an ad hoc basis as the Buddha encountered various behavioral problems or disputes among his followers. Each major early Buddhist tradition had its own variant text of code of discipline for vihara life. Major vihara appointed a vihara-pala, the one who managed the vihara, settled disputes, determined sangha's consent and rules, and forced those hold-outs to this consensus.[30]

Three early influential monastic fraternities are traceable in Buddhist history.[31] The Mahavihara established by Mahinda was the oldest. Later, in 1st century BCE, King Vattagamani donated the Abhayagiri vihara to his favored monk, which led the Mahavihara fraternity to expel that monk.[31] In 3rd century CE, this repeated when King Mahasena donated the Jetavana vihara to an individual monk, which led to his expulsion. The Mahinda Mahavihara led to the orthodox Theravada tradition.[31] The Abhayagiri vihara monks, rejected and criticized by the orthodox Buddhist monks, were more receptive to heterodox ideas and they nurtured the Mahayana tradition. The Jetavana vihara monks vacillated between the two traditions, blending their ideas.[31]

Viharas of the Pāla era

A range of monasteries grew up during the Pāla period in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar) and Bengal. According to Tibetan sources, five great mahaviharas stood out: Vikramashila, the premier university of the era; Nalanda, past its prime but still illustrious, Somapura, Odantapurā, and Jagaddala.[33] According to Sukumar Dutt, the five monasteries formed a network, were supported and supervised by the Pala state. Each of the five had their own seal and operated like a corporation, serving as centers of learning.[34]

Other notable monasteries of the Pala Empire were Traikuta, Devikota (identified with ancient Kotivarsa, 'modern Bangarh'), and Pandit Vihara. Excavations jointly conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India and University of Burdwan in 1971-1972 to 1974-1975 yielded a Buddhist monastic complex at Monorampur, near Bharatpur via Panagarh Bazar in the Bardhaman district of West Bengal. The date of the monastery may be ascribed to the early medieval period. Recent excavations at Jagjivanpur (Malda district, West Bengal) revealed another Buddhist monastery (Nandadirghika-Udranga Mahavihara)[35] of the ninth century.

Nothing of the superstructure has survived. A number of monastic cells facing a rectangular courtyard have been found. A notable feature is the presence of circular corner cells. It is believed that the general layout of the monastic complex at Jagjivanpur is by and large similar to that of Nalanda. Beside these, scattered references to some monasteries are found in epigraphic and other sources. Among them Pullahari (in western Magadha), Halud Vihara (45 km south of Paharpur), Parikramana vihara and Yashovarmapura vihara (in Bihar) deserve mention. Other important structural complexes have been discovered at Mainamati (Comilla district, Bangladesh). Remains of quite a few viharas have been unearthed here and the most elaborate is the Shalban Vihara. The complex consists of a fairly large vihara of the usual plan of four ranges of monastic cells round a central court, with a temple in cruciform plan situated in the centre. According to a legend on a seal (discovered at the site) the founder of the monastery was Bhavadeva, a ruler of the Deva dynasty.[citation needed]

Southeast Asia

As Buddhism spread in southeast Asia, monasteries were built by local kings. The term vihara referred to the assembly hall of these monasteries. Many of these viharas continue to play an important role in the modern era practice of Theravada Buddhism. For example, during the twelfth lunar month in Thailand, lay Buddhists visit a monastery and circumambulate the vihara and the reliquary as a means to earn merit. Devotees may hold banana boats containing burning incense sticks, flowers, sticky rice and few coins as they complete the circle. These boats are then carried to a local river or pond and set afloat.[36] At other times, the lay Buddhists gather for kathina ceremonies in the vihara where they donate robes, soap, towels, canned food, cigarettes and other material goods for the monks, with the belief that the merit they so earn will enable them to live in heavenly samsara after some future rebirth.[37][38] Many of these Theravada viharas feature a Buddha image that is considered sacred after it is formally consecrated by the monks.[37]

Image gallery

-

Cave 4, Ajanta Caves

-

Entrance to a vihara hall at Kanheri Caves

-

Wall carvings at Kanheri Caves

-

Simple slab abode beds in vihara at Kanheri Caves

-

Doorways of a Vihara, Bedse Caves

See also

- Brahma-vihara

- Kanheri Caves

- List of Buddhist temples

- Nava Vihara

- Wat - a Buddhist temple in Cambodia, Laos or Thailand.

- Gompa

Notes

- ↑ Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. p. 625. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=JqHPpNaZfNwC&pg=PA625.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Vihara, Monier Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English Dictionary Etymologically Arranged, Oxford University Press, page 1003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Nayanjot Lahiri (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 181–183. ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=JaVRCgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stella Kramrisch (1946). The Hindu Temple. Princeton University Press (Reprint: Motilal Banarsidass). pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-81-208-0223-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=NNcXrBlI9S0C&pg=PA137.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Paul Dundas (2003). The Jains. Routledge. pp. 203–204. ISBN 1-134-50165-X. https://books.google.com/books?id=X8iAAgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Gomaṭeśvara sahasrābdī mahotsava darśana, Niraj Jain, Śravaṇabelagola Digambara Jaina Muzaraī Insṭīṭyuśaṃsa Mainejiṅga Kameṭī, 1984, Page 265

- ↑ Tulasī prajñā, Jaina Viśva Bhāratī., 1984, Page 29

- ↑ Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, p. 67 and see individual entries, 1989, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

- ↑ Hermann Oldenberg; Friedrich Max Müller (1892). The Grihya-sûtras, Rules of Vedic Domestic Ceremonies. Clarendon Press: Oxford. pp. 54–56, 330–331. https://books.google.com/books?id=_xBWAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA330.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Brian K. Smith (1998). Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-81-208-1532-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=nkruE6UCz54C&pg=PA151.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Vihara, Pali English Dictionary, T. W. Rhys Davids, William Stede, editors; Pali Text Society; page 642

- ↑ John Powers; David Templeman (2012). Historical Dictionary of Tibet. Scarecrow. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-8108-7984-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=LVlyX6iSDEQC&pg=PA204.

- ↑ Karl H. Potter (2003). Buddhist Philosophy from 350 to 600 A.D.. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 265. ISBN 978-81-208-1968-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=5WHHJ6O7b-IC&pg=PA265.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–249. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q5kI02_zW70C.

- ↑ Paul Gwynne (30 May 2017). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. Wiley. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-118-97228-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=sU8nDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA51.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 66. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8-TxcO9dfrcC&pg=PA66.

- ↑ F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–246. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q5kI02_zW70C.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Johannes Bronkhorst (2011). Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism. BRILL Academic. pp. 96–97 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-20140-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=BaX58-E5-3MC.

- ↑ Harle, 48, 54-56, 119-120; Michell, 67

- ↑ Harle, 132; Michell, 67

- ↑ Michell, 359, 374

- ↑ Michell, 351-352

- ↑ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. p. 34. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Behrendt, Kurt A. (2004) (in en). Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. pp. 168-171. ISBN 9004135952. https://books.google.com/books?id=C9_vbgkzUSkC&pg=PA168.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Susan L. Huntington (1990), Early Buddhist Art and the Theory of Aniconism, Art Journal, Volume 49, 1990 - Issue 4: New Approaches to South Asian Art, pages 401-408

- ↑ Himanshu Prabha Ray (2017). Archaeology and Buddhism in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-351-39432-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=A-wrDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT66.

- ↑ Pia Brancaccio (2010). The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion. BRILL Academic. pp. 61 with footnote 80. ISBN 90-04-18525-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=m_4pXm7dD78C.

- ↑ "Entrance Cave 9, Ajanta". art-and-archaeology.com. http://www.art-and-archaeology.com/india/ajanta/aja02.html. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Frederick M. Asher (1980). The Art of Eastern India: 300 - 800. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-4529-1225-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=d-gGxzx6wxIC&pg=PA15.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Jonathan A. Silk (2008). Managing Monks: Administrators and Administrative Roles in Indian Buddhist Monasticism. Oxford University Press. pp. 39-58, 137–158. ISBN 978-0-19-532684-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=3RYTDAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=u0sg9LV_rEgC.

- ↑ Susan L. Huntington (1984). The "Påala-Sena" Schools of Sculpture. Brill. pp. 164–165. ISBN 90-04-06856-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=xLA3AAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayogini: Her Visualization, Rituals, and Forms. Wisdom Publications. p. 15. ISBN 0-86171-329-X.

- ↑ Dutt, Sukumar (1962). Buddhist Monks And Monasteries Of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. pp. 352–3. OCLC 372316.

- ↑ "Jagjivanpur, A newly discovered Buddhist site in west Bengal". Information & Cultural Affairs Department, Government of West Bengal. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090809033739/http://www.tathyabangla.org.in/public/i_cadeprt/archeology/arch3.asp.

- ↑ Donald K. Swearer (1995). The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-4384-2165-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=LReQ_nw9HEMC&pg=PA33.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Donald K. Swearer (1995). The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-1-4384-2165-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=LReQ_nw9HEMC&pg=PA33.

- ↑ Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–262. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=u0sg9LV_rEgC.

References

- Chakrabarti, Dilip K. (October 1995). "Buddhist Sites across South Asia as Influenced by Political and Economic Forces". World Archaeology 27 (2): 185–202. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980303.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Khettry, Sarita (2006). Buddhism in North-Western India: Up to C. A.D. 650. Kolkata: R.N. Bhattacharya. ISBN 978-81-87661-57-3.

- Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1989, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

- Mitra, D. (1971). Buddhist Monuments. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 0-89684-490-0.

- Rajan, K.V. Soundara (1998). Rock-cut Temple Styles: Early Pandyan Art and The Ellora Shrines. Mumbai: Somaiya Publications. ISBN 81-7039-218-7.

- Tadgell, C. (1990). The History of Architecture in India: From the Dawn of Civilization to the End of the Raj. London: Phaidon. ISBN 1-85454-350-4.

External links

- Lay Buddhist Practice: The Rains Residence - A short article on the meaning of Vassa, and its observation by lay Buddhists.

- Mapping Buddhist Monasteries A project aiming to catalogue, crosscheck, verify and interrelate, tag and georeference, chronoreference and map online (using KML markup & Google Maps technology).