Physics:Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae ("The Great Art of Light and Shadow") is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher.[1] It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was published in Amsterdam in 1671 by Johann Jansson.[2]:xxxiii Ars Magna was the first description published in Europe of the illumination and projection of images.[3] The book contains the first printed illustration of Saturn and the 1671 edition also contained a description of the magic lantern.[4]:15

Ars magna lucis et umbrae followed soon after Kircher's work on magnetism, Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (1641) and the title was a play on words. In his introduction Kircher notes that the word 'magna' alluded to the powers of the magnet, so that the title could also be read “The Magnetic Art of Light and Shadow”.[5] The work was well known for several decades.[6]:101

Content

Ars Magna is the first of Kircher's works to follow a symbolic structure. It consists of ten books, represented as the ten strings of the instrument with which the psalmist praises the Lord in Psalm 143.[4]:15 The ten books also have a kabbalistic significance, betokening the ten sefirot.[7]:23

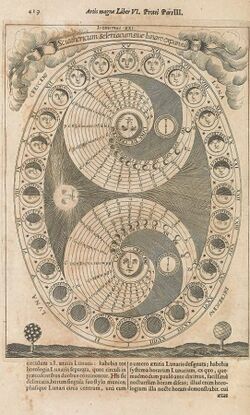

Kircher dealt comprehensively with many different aspects of light, including physical, astronomical, astrological and metaphysical. He discussed phenomena such as fluorescence, phosphorescence and luminescence, optics and perspective.[6]:101 He also described pareidolia.[8] The work deals first with the Sun, Moon, stars, comets, eclipses and planets. It also discusses phenomena related to light, such as optical illusions, colour, refraction, projection and distortion. The work includes one of the first scientific on phosphorescence and the luminosity of fireflies. He devoted much care to descriptions of instruments such as sundials, moondials and mirrors that make use of light. He had written extensively on these subjects in an earlier work, the Primitiae gnomoniciae catroptricae. Kircher also discussed the "magic lantern" - he is sometimes, incorrectly, credited with inventing this device.[2]:13

In the section “Cosmometria Gnomonica”, Kircher set out to show how, by measuring sunlight and shadow, it was possible to measure the universe itself. He estimated the depth of the Earth's atmosphere, the distance between the Moon and the Earth, the diameter of the Sun and its distance from the Earth.[9]

The book concludes with a verse:

"Disperge has radiis animae fulgentibus umbras

Ut tua sit mea lux lux mea sit tua lux"

("Disperse the shadows of the soul with splendid rays, so that your light be mine, and my light, yours.")[7]:72

Illustrations

Ars Magnes Lucis et Umbrae contained thirty-four engraved plate illustrations.[4]:50 The illustration of Saturn was a woodcut. The planet was represented as a sphere with two nearby ellipses, as the existence of the rings had not yet been discovered in 1641. By the time the second edition was published in 1671, it was understood that Saturn had rings and not two large satellites, but Kircher did not correct the illustration and it was reprinted unchanged.[4]:130

Frontispiece

The frontispiece for the book by Pierre Miotte combines the physical, metaphysical and allegorical qualities of light.[6]:101 It depicts three realms, the divine, the starry and the earthly. In the divine realm the name of God appears in the Hebrew tetragrammation, surrounded by the nine orders of angels. Immediately below this are represented the two highest means by which humans can understand God's plan, sacred authority ('auctoritas sacra') and reason ('ratio').[4]:23–28

In the centre of the starry realm below is a celestial sphere with the signs of the zodiac. On the left site the sun-god, his body marked with the signs of the zodiac that govern the respective parts of the body. He carries a caduceus, a token of Hermes, topped with the symbol of an eye, that may denote hermetic wisdom. His feet rest upon the double-headed eagle of the Habsburgs. From the clouds beneath a hand emerges holding a lantern revealing the text of a book, labelled profane authority ('auctoritas profana') (that is, the writings of ancient pagan philosophers and other authorities). Facing the sun-god is the moon-goddess, covered in stars and holding a shield which reflects the light of the Sun down to the Earth below. She holds a staff topped with an owl, symbol of Athena, and her feet rest on a peacock, symbol of Juno. Beneath her a finger points to the fourth source of knowledge, the senses ('sensus'), represented by a telescope casting an image of the sun onto a sheet of paper.[4]:23–28 (Ars Magna contained Kircher's own drawings of sunspots).[4]:127

Above the earthly level appears the portrait of the Archduke Ferdinand, to whom the book was dedicated. Beneath this, on the left, is a formal garden, perhaps demonstrating the life-giving properties of sunlight and of enlightenment. Here the rays of the Moon are cast into a moondial. On the right a ray of sunlight penetrates the roof of a dark cave, and a mirror casts reflections on the wall of the cave. This is a representation of Plato's famous allegory of the cave.[4]:23–28[10][11]

Universal horoscope of the Society of Jesus

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae contained many designs for sundials and related devices, including a large foldout sheet that allowed the user to know the time in every part of the world where the Jesuits had missions. Kircher intended to be of practical use, and suggested that it be mounted on wood, and then oriented precisely by use of a sundial. The rose at the bottom of the sheet could be cut out and mounted on stiff paper so that it could be rotated to show the hours. The main design is in the shape of an olive tree. When the sheet is hung vertically, with pins placed at the nodes of the tree, the shadows of all the pins align to spell "IHS", the logo of the Society of Jesus.[12][4]:202

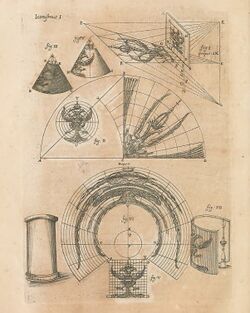

Magic lantern

Kircher's unusual depiction of the magic lantern has been taken by some critics to mean that he had not actually built one or seen it operate, since the illustration shows the mirror not properly alighted with the light source and the glass slider appears in front of the lens tube rather than behind it. Some argue that these anomalies are due to mistakes by the Dutch publisher Waesberghe; however others hold that the mechanism would work as depicted and that it was a variant of the normal type, designed as an analogicical demonstration of the Neoplatonic metaphysics of light.[13]:66

External links

- Digital copy of Ars Magna on the Internet Archive

- Digital copy with index on the Herzog August Library

References

- ↑ Helmar Schramm; Ludger Schwarte; Jan Lazardzig (22 August 2008). Collection - Laboratory - Theater: Scenes of Knowledge in the 17th Century. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 273–. ISBN 978-3-11-020155-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=VrC_gsY4ED8C&pg=PA273. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Merrill, Brian L.. "Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680): Jesuit scholar : an exhibition of his works in the Harold B. Lee Library collections". Friends of Brigham Young University Library. http://www.fondazioneintorcetta.info/pdf/biblioteca-virtuale/documento970/JesuitScholar.pdf. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ↑ Robert Bud; Deborah Jean Warner; Simon Chaplin (1998). Instruments of Science: An Historical Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-8153-1561-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=1AsFdUxOwu8C&pg=PA365. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Godwin, Joscelyn (2015). Athanasius Kircher's Theatre of the World. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-465-4.

- ↑ John Glassie (8 November 2012). A Man of Misconceptions: The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-59703-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=if-MczzIOBQC.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Stuart Clark; S. Clark (29 March 2007). Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-925013-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=T7FccuaGJqsC&pg=PR10. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Anna Maria Partini (2004). Athanasius Kircher e l'alchimia: testi scelti e commentati. Edizioni Mediterranee. ISBN 978-88-272-1725-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=cBzbL1jsMrMC&pg=PA23. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ↑ Paula Findlen (2 August 2004). Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. Routledge. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-135-94844-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=klaSAgAAQBAJ. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ↑ "Measuring the Universe, Marvellous Inventions. Athanasius Kircher's "Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae"". Worcester Cathedral Library. 4 November 2019. https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2019/11/04/measuring-the-universe-marvellous-inventions-athanasius-kirchers-ars-magna-lucis-et-umbrae-1646-blog-3/. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ↑ Siegfried Zielinski (15 October 2019). Variations on Media Thinking. University of Minnesota Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4529-6070-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=HJq4DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT322. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ Marina Warner (2006). Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media Into the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-19-929994-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=yUBdtTvey4IC&pg=PA138. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ "Universal horoscope of the Society of Jesus". Stanford University. https://web.stanford.edu/group/kircher/cgi-bin/site/?attachment_id=647. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ↑ Jill H. Casid (1 January 2015). Scenes of Projection: Recasting the Enlightenment Subject. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-4529-4250-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=qy90DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT66.

|