Physics:Crystal ball

A crystal ball is a crystal or glass ball and common fortune-telling object. It is generally associated with the performance of clairvoyance and scrying in particular.

It is also called a crystal sphere, gazing ball, or shew stone (or show stone – "shew" is an archaic spelling of "show"). In neopaganism it is sometimes called by the modern term orbuculum.

In more recent times, the crystal ball has been used for creative photography with the term lensball commonly used to describe a crystal ball used as a photography prop.[1][2]

History

In the first century CE, Pliny the Elder describes use of crystal balls by soothsayers ("crystallum orbis").[3] By the fifth century CE, scrying was widespread within the Roman Empire and was condemned by the early medieval Christian Church as heretical.[4]

John Dee was a noted British mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I. He devoted much of his life to alchemy, divination, and Hermetic philosophy, of which the use of crystal balls was often included.[5]

Crystal gazing was a popular pastime in the Victorian era, and was claimed to work best when the Sun is at its northernmost declination. Immediately before the appearance of a vision, the ball was said to mist up from within.[4]

The use of crystal balls for divination also has a long history with the Romani people.[6] Fortune tellers, known as drabardi,[7] traditionally use crystal balls as well as cards to seek knowledge about future events.[8]

Art of scrying

The process of scrying often involves the use of crystals, especially crystal balls, in an attempt to predict the future or otherwise divine hidden information.[9] Crystal ball scrying is commonly used to seek supernatural guidance while making difficult decisions in one's life (e.g., matters of love or finances).[10][11]

When the technique of scrying is used with crystals, or any transparent body, it is known as crystallomancy or crystal gazing.

In stage magic

Crystal balls are popular props used in mentalism acts by stage magicians. Such routines, in which the performer answers audience questions by means of various ruses, are known as crystal gazing acts. One of the most famous performers of the 20th century, Claude Alexander, was often billed as "Alexander the Crystal Seer".[12]

Ball lens properties

A crystal ball is an optical lens. In particular, a ball lens (or "lensball") is a bi-convex spherical lens with the same radius of curvature on both sides, and diameter equal to twice the radius of curvature. The same optical laws may be applied to analyze its imaging characteristics as for other lenses.

As a lens, a transparent sphere of any material with refractive index ( n ) greater than air ( n = 1.00 ) bends rays of light to a focal point; for most glassy materials the focal point is only slightly beyond the surface of the ball. Ball lenses have extremely high optical aberration, including large amounts of coma and field curvature compared to conventional lenses.

The refractive index of typical materials used for crystal balls ( quartz: n = 1.46 ; window glass: n = 1.52 ), focus infinity to a point just outside the surface of the sphere, on the side of the ball diametrically opposite to where the rays entered.[citation needed]

Omnidirectional lens

Since a crystal ball has no edges like a conventional lens, the image-forming properties are omnidirectional (independent of the direction being imaged). This effect is exploited in the Campbell–Stokes recorder, a scientific instrument which records the brightness of sunlight by burning the surface of a paper card bent around the sphere. The device, itself fixed, records the apparent motion and intensity of the sun across the sky, burning an image of the sun's motion across the card.[citation needed]

The omnidirectional burning glass effect can occur with a crystal ball that is brought into full sunlight. The image of the sun formed by a large crystal ball will burn a hand that is holding it, and can ignite dark-coloured flammable material placed near it.[13]

Lensball photography

Ball lenses are used by photographers to take novel extreme wide-angle photos.[1][2][11] The ball lens (or "lensball") is placed fairly close to the camera and the camera's own lenses are used to focus an image through the lensball. If the camera is close to the ball lens, the background around the ball will be completely blurred. The further the camera lies from the ball lens, the better the background will come into focus.[14]

Ball lenses of extremely refractive glass

For materials with refractive index greater than 2, objects at infinity form an image inside the sphere. The image is not directly accessible; the closest accessible point is on the sphere's surface directly opposite the source of light. Most clear solids used for making lenses have refractive indices between 1.4 and 1.6; only a few rare materials have a refractive index of 2 or higher (cubic zirconia, Boron nitride (c‑BN & w‑BN), diamond, moissanite). Many of those few are either too brittle, too soft, too hard, or too expensive to for practical lens making (columbite, rutile, tantalite, tausonite). For a refractive index of exactly 2.0, the image forms on the surface of the sphere, and the image may be viewed on an translucent object or diffusing coating on the imaging side of the sphere.[citation needed]

Famous crystal balls in history

A crystal ball lies in the Sceptre of Scotland that is alleged to have originally been possessed by pagan druids.[15]

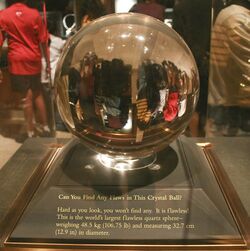

Philadelphia's University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (also called Penn Museum for short) displays the third largest crystal ball[16] as the central object in its Chinese Rotunda. Weighing 49 pounds (22 kg), the sphere is made of quartz crystal from Burma and was shaped through years of constant rotation in a semi-cylindrical container filled with emery, garnet powder, and water. The ornamental treasure was purportedly made for the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) during the Qing dynasty in the 19th century, but no evidence as to its actual origins exists.

In 1988, the crystal ball and an ancient Egyptian statuette[17] which depicted the god Osiris were stolen from the Penn Museum but were recovered three years later with no damage done to either object.[18]

A crystal ball was among the grave-goods of the Merovingian King, Childeric I (c. 437–481 AD).[19] The grave-goods were discovered in 1653. In 1831, they were stolen from the royal library in France where they were being kept. Few items were ever recovered. The crystal ball was not among them.

See also

- Campbell–Stokes recorder

- Crystal skull

- Gazing ball

- Palantír

- Salvator Mundi (Leonardo), da Vinci's "Savior of the World" painting depicting Christ holding a crystal ball

- Seer stone (Latter Day Saints)

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bond, Simon (22 December 2016). "Create glass ball landscapes". https://digital-photography-school.com/create-glass-ball-landscapes/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Lensball photography". https://www.refractique.co.uk.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (1831). Caii Plinii Secundi Historiæ naturalis libri xxxvii, cum selectis comm. J. Harduini ac recentiorum interpretum novisque adnotationibus. p. 579. https://books.google.com/books?id=HNkIAAAAQAAJ&q=%22orbis+crystallum%22. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Crystal gazing". Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/crystal-gazing. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "John Dee's crystal ball". http://ensemble.va.com.au/tableau/suzy/TT_ResearchProjects/Hexen2039/JohnDee/JD_CBall.html.

- ↑ "Where did crystal balls come from?". May 21, 2019. https://historydaily.org/crystal-balls-history-origin.

- ↑ "Fortune telling as part of the Roma Culture". https://rozvitok.org/en/fortune-telling-as-part-of-the-roma-culture/.

- ↑ "ЦЫГАНЕ И ЦЫГАНСКИЕ ГАДАНИЯ". http://sekukin.narod.ru/templ14.html.

- ↑ "scry". scry. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/scry. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ↑ Chauran, Alexandra (2011). Crystal Ball Reading for Beginners: A down to Earth guide. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Lensball photography". https://lensball.com.au.

- ↑ David Copperfield's History of Magic. Liwag, Homer (photographer) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. 2021. ISBN 978-1-9821-1291-2. OCLC 1236259508. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1236259508.

- ↑ "Crystal ball starts fire at Okla. home". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 29 January 2004. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A61176-2004Jan29.html.

- ↑ "Seven tips for awesome lensball photography". Australian Photography. 31 March 2020. https://www.australianphotography.com/photo-tips/seven-tips-for-awesome-lensball-photography. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ↑ Ferguson, Sibyl (30 June 2005). Crystal Ball: Stones, amulets, and talismans for power, protection, and prophecy. Weiser Books. pp. 59–60, 29. ISBN 978-1-57863-348-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=4V0x3_K98_wC&pg=PA59.

- ↑ "Crystal sphere". University of Pennsylvania. http://www.penn.museum/collections/object/335728.

- ↑ "Statue". University of Pennsylvania. http://www.penn.museum/collections/object/276512.

- ↑ "Penn Museum crystal ball, statue stolen; guard ignored burglar alarms". 1988-11-12. http://articles.philly.com/1988-11-12/news/26248970_1_crystal-ball-alarms-security-guard.

- ↑ Chifflet, J.-J. (1665). Anastasis Childerici I. Francorum Regis, site Thesaurus sepulchralis Tornaci Neruiorum effossus, & commentario illustratus. https://archive.org/details/anastasischilder00chif/page/242/mode/2up.

Further reading

- Lang, Andrew (1900). The Making of Religion. London, UK / New York, NY / Bombay, IN: Longmans, Green, and Co.. pp. 83–104.

- Munn, Geoffrey (2018). The Sphere of Magical Thinking: The enchanting history of crystal balls.

External links