Physics:Dark state

In atomic physics, a dark state refers to a state of an atom or molecule that cannot absorb (or emit) photons. All atoms and molecules are described by quantum states; different states can have different energies and a system can make a transition from one energy level to another by emitting or absorbing one or more photons. However, not all transitions between arbitrary states are allowed. A state that cannot absorb an incident photon is called a dark state. This can occur in experiments using laser light to induce transitions between energy levels, when atoms can spontaneously decay into a state that is not coupled to any other level by the laser light, preventing the atom from absorbing or emitting light from that state.

A dark state can also be the result of quantum interference in a three-level system, when an atom is in a coherent superposition of two states, both of which are coupled by lasers at the right frequency to a third state. With the system in a particular superposition of the two states, the system can be made dark to both lasers as the probability of absorbing a photon goes to 0.

Two-level systems

In practice

Experiments in atomic physics are often done with a laser of a specific frequency (meaning the photons have a specific energy), so they only couple one set of states with a particular energy to another set of states with an energy . However, the atom can still decay spontaneously into a third state by emitting a photon of a different frequency. The new state with energy of the atom no longer interacts with the laser simply because no photons of the right frequency are present to induce a transition to a different level. In practice, the term dark state is often used for a state that is not accessible by the specific laser in use even though transitions from this state are in principle allowed.

In theory

Whether or not we say a transition between a state and a state is allowed often depends on how detailed the model is that we use for the atom-light interaction. From a particular model follow a set of selection rules that determine which transitions are allowed and which are not. Often these selection rules can be boiled down to conservation of angular momentum (the photon has angular momentum). In most cases we only consider an atom interacting with the electric dipole field of the photon. Then some transitions are not allowed at all, others are only allowed for photons of a certain polarization. Consider for example the hydrogen atom. The transition from the state with mj=-1/2 to the state with mj=-1/2 is only allowed for light with polarization along the z axis (quantization axis) of the atom. The state with mj=-1/2 therefore appears dark for light of other polarizations. Transitions from the 2S level to the 1S level are not allowed at all. The 2S state can not decay to the ground state by emitting a single photon. It can only decay by collisions with other atoms or by emitting multiple photons. Since these events are rare, the atom can remain in this excited state for a very long time, such an excited state is called a metastable state.

Three-level systems

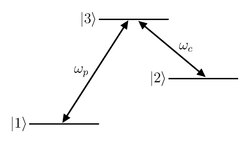

We start with a three-state Λ-type system, where and are dipole-allowed transitions and is forbidden. In the rotating wave approximation, the semi-classical Hamiltonian is given by

with

where and are the Rabi frequencies of the probe field (of frequency ) and the coupling field (of frequency ) in resonance with the transition frequencies and , respectively, and H.c. stands for the Hermitian conjugate of the entire expression. We will write the atomic wave function as

Solving the Schrödinger equation , we obtain the solutions

Using the initial condition

we can solve these equations to obtain

with . We observe that we can choose the initial conditions

which gives a time-independent solution to these equations with no probability of the system being in state .[1] This state can also be expressed in terms of a mixing angle as

with

This means that when the atoms are in this state, they will stay in this state indefinitely. This is a dark state, because it can not absorb or emit any photons from the applied fields. It is, therefore, effectively transparent to the probe laser, even when the laser is exactly resonant with the transition. Spontaneous emission from can result in an atom being in this dark state or another coherent state, known as a bright state. Therefore, in a collection of atoms, over time, decay into the dark state will inevitably result in the system being "trapped" coherently in that state, a phenomenon known as coherent population trapping.

See also

References

- ↑ P. Lambropoulos; D. Petrosyan (2007). Fundamentals of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information. Berlin; New York: Springer.

|