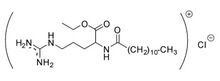

Physics:Ethyl lauroyl arginate hydrochloride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

ethyl (2S)-5-(diaminomethylideneamino)-2-(dodecanoylamino)pentanoate;hydrochloride

| |

| Other names

Ethyl N(alpha)-lauroyl-L-arginate

Lauric arginate ethyl ester | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H41ClN4O3 | |

| Molar mass | 421.02 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Ethyl lauroyl arginate hydrochloride (LAE), Nα-Lauroyl-L-arginine ethyl ester hydrochloride (CAS number 60372-77-2), hereinafter LAE, is an antimicrobial compound based on natural building blocks such as lauric acid and L-arginine.

LAE is an amino acid-based surfactant with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, high biodegradability and low toxicity. Due to these features, LAE is a preservative used in food and cosmetic formulations. LAE is also known in the EU as E-243.[1][2]

History

The first synthesis of ethyl lauroyl arginate hydrochloride and its antimicrobial properties were reported in 1976. In the earlies 1980s, LAMIRSA together with Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC, Barcelona) began to investigate a new approach to the control of pathogens in food through the application of cationic surfactants based on natural building blocks that inhibit the proliferation of a huge variety of microorganisms, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, moulds and yeasts. In 1995 LAMIRSA together with CSIC patented a new process to synthesize LAE.[2]

Description

LAE is a white solid, soluble in deionized water up to 247 g/kg at 20 °C with a melting point from 57 °C to 58 °C. Its partition coefficient between olive oil and water is 0.07; it allows LAE to be located in the water fraction, which is more susceptible to microbial contamination.[3] This property gives LAE an advantage over other preservatives with a different chemical structure intended for the same applications.

LAE shows chemical stability at a pH range between 3 and 7[4][5] and maintains its antimicrobial activity in this interval.

Applications in food and cosmetic industries

Its low toxicity and remarkable antimicrobial features make LAE a product with a wide application within the food and cosmetic preservation fields. The use of LAE means a great technological innovation toward manufacturing products with better preservation qualities. In this connection, MIRENAT is a range of formulated products based on LAE intended for the food industry. At the same time, AMINAT is a range of formulated products based on LAE intended for the cosmetic industry.

MIRENAT range of products reduces the risk of food spoilage as it diminishes the presence of pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., and Escherichia coli. MIRENAT also prolongs the shelf life of food products because of its broad spectrum of activity against all types of microorganisms. Furthermore, it does not modify the organoleptic properties of the treated products.

The antimicrobial activity of LAE solutions applied in food has been widely studied. For instance, Luchansky et al. studied the preservation of commercially prepared ham using LAE solutions.[6] Initially, hams were surface inoculated with a five-strain cocktail of Listeria monocytogenes (7 log10 CFU/ ham), added to shrink-wrap bags that already contained LAE, vacuum-sealed, and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. In samples treated with 2, 4, 6, and 8 mL of 5% Mirenat-N (i.e., 0.5% of LAE), pathogen levels decreased dramatically by 5.1, 5.4, and 5.5 log10 CFU/ham. In addition, samples treated with 8 mL of 5% Mirenat-N for 28 days of refrigerated storage still showed pathogen levels below the limit of detection (i.e., 1.48 log10). Similar assays were also conducted using an initial inoculum of 3 log10 CFU/ham. Here, samples treated with 2, 4, 6, and 8 mL of 5% Mirenat-N and stored at 4 °C for 24 h showed pathogen levels below the detection limit for all volumes assayed. Furthermore, samples treated with 6 and 8 mL of 5% Mirenat-N for 28 days of refrigerated storage still showed pathogen levels below the detection limit.

Soni et al. also studied the reduction of Listeria monocytogenes in cold-smoked salmon by LAE.[7] The authors reported that treatment of cold-smoked salmon containing 3.5 log10 CFU/cm2 Listeria monocytogenes with LAE (200 ppm) showed strong listericidal action. Thus, treatment with 200 ppm LAE at 4 °C yielded 2.7 and 5.5 log10 CFU mL−1 reduction after 1 h and 4 h incubation, respectively. After 24 h incubation at 4 °C, no Listeria monocytogenes survival was recovered. At 30 °C, Listeria monocytogenes reductions were 3.8, 7.0, and 8.0 log10 CFU mL−1 after 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h incubation treatment, respectively.

AMINAT range of products are preservatives for personal care products such as cosmetic creams, lotions, body milks, hair conditioners, and sunscreen formulas or can be used as an active ingredient in soaps, anti-dandruff shampoos, deodorants, and oral care products. AMINAT combines a high antimicrobial efficacy with innocuousness, non-sensitizing, and non-skin irritating features. It also provides smoothness to skin and hair because of its cationic nature.

AMINAT is an environmentally acceptable cosmetic ingredient with the certifications Ecocert, Cosmos, and Natrue.

Vedeqsa scientists evaluated the activity of LAE in anti-dandruff applications.[8] The authors performed suspension tests to compare the antimicrobial activity in vitro of several formulations against Malassezia furfur, yeast involved in the proliferation of dandruff. The results demonstrated that the action of the shampoo containing LAE was comparable to the shampoo containing the active zinc pyrithione and slightly superior to that of the shampoo containing the active piroctone olamine. In vivo assays were also performed. Thus, a dermatologist evaluated the dandruff severity of twenty volunteers before and after a four-week treatment. Shampoo containing LAE showed comparable or superior performance to the classic anti-dandruff active agents, with a better toxicological and eco-toxicological profile. The authors also evaluated the activity of LAE in anti-acne applications. Here, suspension tests were performed to compare the antimicrobial activity in vitro of several dermo-purifying gels against Propionibacterium acnes, a Gram-positive bacterium involved in acne formation. Results revealed that gels containing LAE had a quicker killing effect than gels containing other active ingredients such as salicylic acid or δ-gluconolactone. The in vivo activity of gel containing LAE was assayed in eleven volunteers with greasy and acne-prone skin for 28 days by applying 1 mL of the gel. The results showed a significant reduction in the number of pimples for each volunteer during the treatment. Furthermore, a 13.5% decrease in the average amount of sebum measured on volunteers showed a sebolytic effect of the gel containing LAE as an active.

Periodontal diseases

LAE has the potential to treat gingivitis and more advanced periodontitis. In a study comparing ethyl lauroyl arginate hydrochloride in 0.147% mouthwash to chlorhexidine (CHX) 0.12% as an adjunctive therapy in the non-surgical treatment of periodontitis, the results showed there were no treatment-related adverse events. Total bacterial count and the specific pathogens were reduced at 4 weeks and 3 months by both types of mouthwash, with no statistical differences between them at either period. It was concluded that 0.147% LAE-containing mouthwash could be an alternative to the use of 0.12% CHX in the non-surgical therapy of periodontitis, considering the similar clinical effects, more stable microbiological improvement, and absence of adverse effects[9]

It is sold as the main active ingredient in Listerine Advanced Defence Gum Treatment[10] and as one of the active ingredients in GUM Activital Mouthwash.[11]

Mechanism of action

Due to its basic guanidine group, LAE is a cationic surfactant. The target of cationic surfactants is the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane, which carries a negative charge often stabilized by the presence of divalent cations such as Mg2+and Ca2+. Initially, the cationic surfactant crosses the cell wall (i.e., external cell envelopes) of bacteria. Then, the antimicrobial agent displays a high binding affinity for the outermost surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (i.e., inner cell envelope). Later, the cationic surfactant's alkyl chain penetrates into the membrane's hydrophobic core. This leads to a progressive leakage of cytoplasmic material, perturbating their metabolic processes, and the normal bacterial cycle is inhibited. Thus, cationic surfactants are considered a "membrane-active agent".[12][13][14]

Dra. Manresa et al. investigated the effects caused by LAE in Salmonella typhymurium and Staphylococcus aureus. LAE caused disturbance in membrane potential and structural changes and loss of cell viability. However, no disruption of cells was detected.[15] Similar effects were also observed on two food-related bacteria such as Yersina enterolitica and Lactobacillus plantarum. Here, flow cytometry, transmission electron microscopy, and potassium leakage assays demonstrated that LAE targets the cytoplasmic membrane causing loss of membrane potential and potassium ions.[16]

Antimicrobial properties

The following tables show the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of LAE against different types of microorganisms, primarily pathogens, giving insight into LAE's broad spectrum antimicrobial activity and great effectiveness. Dr. Manresa evaluated the antimicrobial activity of LAE in the Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Barcelona.[17]

Further information concerning the antimicrobial properties of LAE is available at [18]

Regulatory status

On 1 September 2005, FDA (Food and Drug Administration) issued the No Objection Letter that LAE is Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) for use as an antimicrobial in several food categories at levels up to 200 ppm. Besides, the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) approved its use in meat and poultry products. LAMIRSA submitted both petitions.

In July 2006 and ratified in July 2012, the Health Secretary of Mexico (Secretaría de Salud) published in its Official Journal that lauric arginate is an allowed substance to be used as a food additive for human consumption.

The EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) evaluated this new additive with a favorable opinion in April 2007 and, in July 2013, assigned it the number E-243. In May 2014, Regulation 506/2014 was published, authorizing a maximum dosage level of 160 ppm for its use in cooked meat products.

In August 2014, Health Canada amended the food legislation to include LAE as a preservative in various foods at a maximum dosage level of 200 ppm.

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) evaluated LAE at its 69th meeting in June 2008. JECFA, a body dependent on WHO (World Health Organization), established an acceptable daily intake of 4 mg/Kg bw for the active material. Codex Alimentarius approved LAE use in several food matrixes up to 200 ppm in July 2011.

In March 2015, LAE was included in the IPA database (Inventory of Substances used as Processing Aids) of the CCFA (Codex Committee on Food Additives) as a processing aid in meat products, poultry, and game.

In March 2016, the CCFA issued a positive evaluation of LAE use in several food categories of meat and poultry. In July 2016, the Codex Alimentarius Commission included these approvals at the 39th meeting.

During the 50th session of the CCFA in March 2018, the proposed uses in food categories of fishery products were accepted. It is expected to be approved by Codex Alimentarius Commission at its 41st meeting scheduled for July 2018.

Other countries where the use of lauric arginate is also approved are Colombia (October 2009), Australia and New Zealand (April 2010), Vietnam (November 2012), Chile (August 2013), Israel (November 2014), Turkey (November 2013) and United Arab Emirates (April 2015), India (2011).

Most recently, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) included in 2018 similar uses and food categories previously recognized by CODEX in 2011. Finally, a request for the use of LAE as a processing aid antimicrobial treatment on raw meat was made to the Government of Canada (Health Canada), resulting in a Letter Of No Objection (LONO) issued in December 2022.

In addition to food applications, LAE has exceptional properties to be used as a cosmetic preservative/active ingredient for a wide range of cosmetic products.

As a cosmetic preservative, LAE was approved in the EU in 2009 according to the Cosmetic Directive to be used up to 0.4% for cosmetic products (except for lips, oral, and spray products) and up to 0.15% in mouthwashes (not children < 10 years). As an active cosmetic ingredient, it was also approved to be used up to 0.8% in soaps, anti-dandruff shampoos, and deodorants (not in spray).

In the same way as EU approval for cosmetic applications, LAE is also confirmed to be used in the US, Mexico, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Japan, with similar applications and reference doses.

In conjunction with its remarkable antimicrobial features, the low toxicity makes LAE a product with a wide application within the food and cosmetics preservation fields. The addition of LAE means a great technological innovation toward manufacturing products with better preservation qualities.

Metabolic and toxicological studies

To many customers, the claim, "no preservative added", often has the false connotation of improved quality. However, proper use of food preservatives can benefit the safety and quality of food.

A series of toxicological experiments carried out by Huntingdon Life Science, Ltd.[19] confirmed the safety of LAE tests, included the metabolism of LAE in animals and humans, mutagenic, acute, subchronic, chronic, reproductive, and developmental toxicity. The results of these studies have been published in the prestigious scientific journal Food Chemical Toxicology.[20]

Metabolism-Toxicokinetics of LAE

Rats were administered an oral dose of 14C-LAE (arginine portion of LAE uniformly radio-labeled) to assess the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of LAE.

Once 14C -LAE was administered to rats, the biotransformation of LAE was followed through the absorption and excretion rates.[21] The excretion rates were determined through the analysis of urine, faeces, and air exhalation, the routes of radioactivity elimination from the body. The following figure (Figure 1) summarises the excretion of radioactivity and the percentage retained in the carcass:

The results in Figure 1 show that approximately 50% of the 14C -LAE administered was absorbed and remained in the carcass of rats, including the liver and gastrointestinal tract.

The next task was to identify and quantify the specific radioactive compounds present in the rats' plasma and define the toxicokinetics based on an in vivo study of metabolism.[22]

Figure 2 reports the percentage of radioactive compounds present in samples of plasma extracted over 4.5 hours after administering 14C-LAE to rats. LAE is rapidly metabolised to Nα-lauroyl-L-arginine (LAS) and then to arginine, which is more slowly metabolised to ornithine. Ornithine is transformed into endogenous products via the urea and citric acid cycles.

The metabolism experiments' results help to establish a biotransformation mechanism for LAE after ingestion. Figure 3 is the proposed pathway of LAE degradation by which it is rapidly hydrolyzed either by loss of the lauroyl side chain to form arginine ethyl ester and/or cleavage of the ethyl ester to form Nα-lauroyl-L-arginine (LAS).

Further hydrolysis of either intermediate results in the generation of arginine, which is then further hydrolyzed to ornithine and urea. Ornithine can be incorporated into the organisms via the urea and citric acid cycles until final degradation to CO2. This metabolic pathway (Figure 4) and the supporting data were presented to the ISSX International Congress in Munich in 2001.[23]

Studies of toxicity

a) Genetic toxicity studies:

As LAE is proposed to be used as a food preservative, genotoxicity studies have been performed to assess LAE's potential to develop genotoxic effects.[24][25][26] The mutagenic potential of LAE in a bacterial system was evaluated through an in vitro technique using strains of Salmonella typhimurium and a mutant strain of Escherichia coli. LAE was also tested for mutagenic potential in an in vitro mammalian cell mutation assay (the mouse lymphoma L5178Y cell). Finally, it was assessed the ability of LAE to induce chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes cultured in vitro. The results obtained indicate that LAE does not possess mutagenic or clastogenic toxicity.

b) Subchronic toxicity study:

In this study, the toxicological profile of LAE was investigated through repeated administration over 13 weeks.[27] The results are used to establish the No-Observed-Adverse-Effect-Level (NOAEL) value, which is the maximum dose of the test substance administered daily that does not produce adverse effects. The dose levels of LAE administered in rats were 5000, 15000, and 50000 ppm. The NOAEL was established at 15000 ppm, corresponding to 1143 mg/kg bw/day in males and 1286 mg/kg bw/day in female rats.

c) Chronic toxicity study:

The results obtained in this study provide enough data to assess the toxicological profile of LAE, which was dietarily administrated during 52 weeks to CD rats.[28] The results obtained establish the NOAEL value and corroborate the information provided by the subchronic studies. The dose levels of LAE administered were 2000, 6000, and 18000 ppm. Based on the calculated intake data, the NOAEL in this study was 6000 ppm, equivalent to 307 mg/kg bw/day in the male and 393 mg/kg bw/day in the female rats. The corresponding LOAEL was 18000 ppm, equivalent to 907 mg/kg bw/day and 1128 mg/kg bw/day for the males and females, respectively, based on local irritant changes in the forestomach.

d) One-generation reproductive and developmental toxicity studies:

These studies aim to identify any adverse effect of LAE in the reproductive system or in the development of fetuses and offspring. Studies were performed with rats and rabbits.[29][30][31][32][33][34] The NOAEL for rabbits was 300 mg/kg bw/day for dams and 1000 mg/kg bw/day for fetuses, while the NOAEL for rats was 2000 mg/kg bw/day for both dams and fetuses.

e) Reproductive and developmental toxicity studies:

This study assesses the influence of LAE on reproductive performance when administered continuously in the diet through two successive generations of CD rats.[35][36] The doses of LAE were administered orally via the diet at concentrations of 2500, 6000, and 15000 ppm for ten weeks before pairing, during pairing, gestation, lactation, and until termination. After recording the clinical conditions of rats through the different generations studied, it was concluded that the NOAEL for reproductive performance and development of F1 and F2 in rats was 15000 ppm.

f) Acute oral and dermal toxicity studies:

Acute toxicity studies evaluate the effects of a single dose of LAE.[37][38] Since LAE can be used in food and cosmetics, acute toxicities were determined based on oral and dermal exposures.

The results indicated that LAE did not cause acute toxicity at the highest dose level tested at 2000 mg/kg bw.

g) Complementary studies regarding cosmetic uses:

Additional studies were performed to demonstrate the safety of LAE when used in cosmetics. The parameters studied were: the capacity of LAE to diffuse through the skin, the potential degree of LAE irritation to the skin and the eyes, and the potential for sensitisation when LAE is repeatedly applied to the skin.[39][40][41]

h) Human studies:

Human metabolic studies of LAE were undertaken after the toxicity studies confirmed that the product is safe. The first human experiment in vitro study helped obtain information about the metabolism of LAE after ingestion, including the potential points of degradation (intestines, liver, and plasma) and its pharmacokinetics.[42] The following figure summarizes experiments performed in vitro in which the metabolism of LAE was determined in simulated intestinal secretions at pH 7.5 in the presence of pancreatin, human plasma, and human hepatocytes.

Under all three in vitro conditions, LAE was rapidly degraded to LAS and subsequently to arginine.

In a second human study, administered LAE to six volunteers divided into two dose groups. All subjects were given clinical examination, and blood samples were extracted for analysis. The clinical examination consisted of identifying any possible adverse physiological effect of LAE after its administration in a single oral dose. The blood work focused on determining the pharmacokinetics of LAE by determining the concentrations of LAE and its by-products.

Two volunteers received an oral dose of 2.5 mg/kg bw.[43] The following figure demonstrates the rapid metabolism of LAE in blood plasma:

Four volunteers received an oral dose of 1.5 mg LAE/kg bw.[44] The following figure summarizes the average results among these volunteers:

LAE was metabolised so quickly that it could not be detected in the blood samples, even those taken immediately following administration. In addition, there were no clinically significant abnormalities in any of the laboratory data for either of the two oral doses.

References

- ↑ Surfactants derived from amino acids. III. Some surface-active properties and antimicrobial activities of the salts of long-chain Nα-acyl-L-arginine esters, Yoshida et al, Yukagaku, 1976, 25 (7), 404-408.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 WO 96/21642, "Use of cationic surfactants as sporicidal agents", issued 2009-06-30

- ↑ "L.A.E. physicochemical properties". Huntingdon Life Science, UK. 2001 – via LMA 025/003269, 2001.

- ↑ "LAE abiotic degradation: hydrolysis as a function of pH (preliminary test)". Huntingdon Life Science, UK. 2000 – via LMA 026/003130, 2000.

- ↑ "LAE abiotic degradation: hydrolysis as a function of pH". Huntingdon Life Science, UK. – via LMA 040/012676.

- ↑ Viability of Listeria monocytogenes on commercially-prepared hams surface treated with acidic calcium sulfate and lauric arginate and stored at 4 °C. Luchansky et al., Meat Science, 2005, 71, 92–99.

- ↑ Reduction of Listeria monocytogenes in cold-smoked salmon by bacteriophage P100, nisin and lauric arginate, singly or in combinations. Soni et al., Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1918-1924.

- ↑ Ethyl Lauroyl Arginate HCl for Natural Preservation. Beltran et al., Cosmetics&Toiletries magazine, 2011,125 (12), 876-883.

- ↑ Pilloni, Andrea; Orrù, Germano; Carere, Mauro; Scano, Alessandra (October 2017). "Adjunctive use of an Ethyl Lauroyl Arginate (LAE)-containing mouthwash in the nonsurgical therapy of periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial". Minerva Stomatologica. 67 (1): 1–11.PMID29087093

- ↑ "Product profile". Listerine Advanced Defence Gum Treatment.

- ↑ "Product profile". Sunstar GUM.

- ↑ Mechanisms of action of disinfectants, Denyer et al., Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad., 1998, 41 (3–4), 261-268. DOI:10.1016/S0964-8305(98)00023-7

- ↑ Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance, McDonnell et al., Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12 (1), 147-179. DOI:10.1128/cmr.12.1.147

- ↑ Cationic antiseptics: diversity of action under a common epithet. Gilbert et al., J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99 (4), 703-15. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02664.x

- ↑ Manresa et al., Cellular effects of monohydrochloride of L-arginine, Nα-lauroyl ethyl ester (LAE) on exposure to Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol., 2004, 96 (5), 903-912. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02207.x

- ↑ Assessment of antimicrobial activity of Nα -lauroyl arginate ethylester (LAE) against Yersinia enterocolitica and Lactobacillus plantarum by flow cytometry and transmission electron microscopy. Science Direct – Food Control, 2016, Vol. 63, p. 1-10. J. Coronel-León, A. López, M.J. Espuny, M.T. Beltran, A. Molinos-Gómez, X. Rocabayera, A. Manresa

- ↑ "Antimicrobial susceptibility in terms of the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of LAE and Mirenat-N". University of Barcelona, Spain. 2004

- ↑ https://www.lauric-arginate.com/mic_values_of_lae_microorganisms_and_pathogens/

- ↑ Huntingdon Life Science Ltd. Woolley Road. Alconbury.Hunringdon. Cambridgeshire PE28 4HS. England.

- ↑ Ruckman, S.A.; Rocabayera, X.; Borzelleca, J.F.; Sandusky, C.B. (2004). "Toxicological and metabolic investigations of the safety of N-α-Lauroyl-l-arginine ethyl ester monohydrochloride (LAE)". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 42 (2): 245–259. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2003.08.022.

- ↑ LMA 017/983414, 1998. Metabolism in the rat. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 033/012117, 2001. In vivo and in vitro metabolism in the rat.Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ Dean, G.; Rocabayera, X.; Mayo, B. M etabolism N"'-lauroyl-L arginine ehtyl ester in the rat. Poster presented on the 6th International ISSX Meeting, October 7–11, Munich 2001.

- ↑ LMA 038/012403, 2001. Bacterial mutation assay. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 052/042549, 2004. LAE in vitro mutation test using mouse lymphoma L5178 Y cells. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 039/012517, 2001. In vitro mammalian chromosome aberration test in human lymphocytes. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 031/004276, 2000. Toxicity study by dietary administration to Han Wistar rats for 13 weeks. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 050/042556. Laurie arginate. Toxicity study by dietary administration to CD rats for 52 weeks. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 011/980114, 1998. Study of tolerance in the rat by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 013/980140, 1998. Preliminary study of embryo-foetal toxicity in the CD rat by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 014/984183, 1998. Study of embryo-foetal toxicity in the CD rat by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 012/980115, 1998. Study of tolerance in the rabbit by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 015/980169, 1998. Preliminary embryo foetal toxicity study in the rabbit by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 016/992096, 1999. Study of embryo-foetal toxicity in the rabbit by oral gavage administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 041/032575, 2003. Preliminary study of effects on reproductive performance in CD rats by dietary administration. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 042/032553, 2004. LAE two generation reproductive performance study by dietary administration to CD rats . Huntingdon Life Science, UK

- ↑ LMA 018/002881/AC, 2000. Acute oral toxicity to the rat (acute classic method). Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 019/002882/AC, 2000. Acute dermal toxicity to the rat. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ Parra, J., 2002. In vitro percutaneous absorption of Nα-lauroyl-L-arginine ethyl ester monohydrochloride (LAE). Centro Superior de lnvestigaciones Científicas, Spain.

- ↑ CD-97/5392T, 1997. Primary eye irritation test in rabbits. Centro de lnvestigaci6n y Desarrollo, S.A.L., Spain.

- ↑ RTC 7980/T/369/2000, 2001. Delayed dermal sensitisation study in the guinea pig (Magnusson & Kligman test). Research Toxicology Centre, Italy.

- ↑ LMA 043/032898, 2003. Nα-lauroyl-L-arginine ethyl ester monohydrochloride in vitro stability. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 047/033421, 2004. LAE an open-label single-doses study to determine the feasibility of measuring LAE and its breakdown products in plasma after oral administration of LAE to healthy male volunteers. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.

- ↑ LMA 049/034017, 2004. LAE and open label single-doses study to determine the feasibility of measuring LAE and its breakdown products in plasma after oral administration of LAE to healthy male volunteers. Huntingdon Life Science, UK.