Physics:Ionic Coulomb blockade

Ionic Coulomb blockade (ICB)[1][2] is an electrostatic phenomenon that appears in ionic transport through mesoscopic electro-diffusive systems (artificial nanopores[1][3] and biological ion channels[2]) and manifests itself as oscillatory dependences of the conductance on the fixed charge in the pore[2] ( or on the external voltage , or on the bulk concentration [1]).

ICB represents an ion-related counterpart of the better-known electronic Coulomb blockade (ECB) that is observed in quantum dots.[4][5] Both ICB and ECB arise from quantisation of the electric charge and from an electrostatic exclusion principle and they share in common a number of effects and underlying physical mechanisms. ICB provides some specific effects related to the existence of ions of different charge (different in both sign and value) where integer is ion valence and is the elementary charge, in contrast to the single-valence electrons of ECB ().

ICB effects appear in tiny pores whose self-capacitance is so small that the charging energy of a single ion becomes large compared to the thermal energy per particle ( ). In such cases there is strong quantisation of the energy spectrum inside the pore, and the system may either be “blockaded” against the transportation of ions or, in the opposite extreme, it may show resonant barrier-less conduction,[6][2] depending on the free energy bias coming from , , or .

The ICB model claims that is a primary determinant of conduction and selectivity for particular ions, and the predicted oscillations in conductance and an associated Coulomb staircase of channel occupancy vs [2] are expected to be strong effects in the cases of divalent ions () or trivalent ions ().

Some effects, now recognised as belonging to ICB, were discovered and considered earlier in precursor papers on electrostatics-governed conduction mechanisms in channels and nanopores.[7][8][9][10][11]

The manifestations of ICB have been observed in water-filled sub-nanometre pores through a 2D monolayer,[3] revealed by Brownian dynamics (BD) simulations of calcium conductance bands in narrow channels,[2][12] and account for a diversity of effects seen in biological ion channels.[2] ICB predictions have also been confirmed by a mutation study of divalent blockade in the NaChBac bacterial channel.[13]

Model

Generic electrostatic model of channel/nanopore

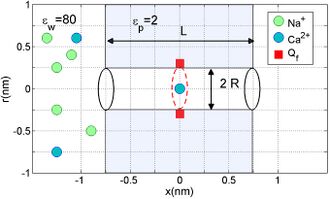

ICB effects may be derived on the basis of a simplified electrostatics/Brownian dynamics model of a nanopore or of the selectivity filter of an ion channel.[8] The model represents the channel/pore as a charged hole through a water-filled protein hub embedded in the membrane. Its fixed charge

is considered as a uniform, centrally placed, rigid ring (Fig.1). The channel is assumed to have geometrical parameters length

nm and radius

nm, allowing for the single-file movement of partially hydrated ions.

The model represents the water and protein as continuous media with dielectric constants and respectively. The mobile ions are described as discrete entities with valence and of radius , moving stochastically through the pore, governed by the self-consistently coupled Poisson's electrostatic equation and Langevin stochastic equation.

The model is applicable to both cationic[9] and anionic[14] biological ion channels and to artificial nanopores.[1][3]

Electrostatics

The mobile ion is assumed to be partially hydrated (typically retaining its first hydration shell[15]) and carrying charge where is the elementary charge (e.g. the ion with ). The model allows one to derive the pore and ion parameters satisfying the barrier-less permeation conditions, and to do so from basic electrostatics taking account of charge quantisation.

The potential energy of a channel/pore containing ions can be decomposed into electrostatic energy[1][2][8] , dehydration energy,[15] and ion-ion local interaction energy : The basic ICB model makes the simplifying approximation that , whence:where is the net charge of the pore when it contains identical ions of valence , the sign of the moving ions being opposite to that of the , represents the electrostatic self-capacitance of the pore, and is the electric permittivity of the vacuum.

Resonant barrier-less conduction

Thermodynamics and statistical mechanics describe systems that have variable numbers of particles via the chemical potential , defined as Gibbs free energy per particle:[16][17], where is the Gibbs free energy for the system of particles. In thermal and particle equilibrium with bulk reservoirs, the entire system has a common value of chemical potential (the Fermi level in other contexts).[16] The free energy needed for the entry of a new ion to the channel is defined by the excess chemical potential [16] which (ignoring an entropy term ) can be written as where is the charging energy (self-energy barrier) of an incoming ion and is its affinity (i.e. energy of attraction to the binding site ). The difference in energy between and (Fig.2.) defines the ionic energy level separation (Coulomb gap) and gives rise to most of the observed ICB effects.

In selective ion channels, the favoured ionic species passes through the channel almost at the rate of free diffusion, despite the strong affinity to the binding site. This conductivity-selectivty paradox has been explained as being a consequence of selective barrier-less conduction.[6][10][17][18] In the ICB model, this occurs when is almost exactly balanced by (), which happens for a particular value of (Fig.2.).[12] This resonant value of depends on the ionic properties and (implicitly, via the -dependent dehydration energy [6][15]), thereby providing a basis for selectivity.

Oscillations of conductance

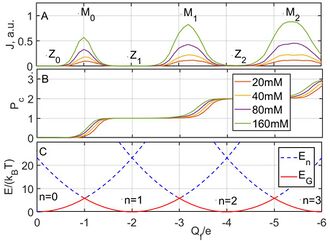

The ICB model explicitly predicts an oscillatory dependence of conduction on

, with two interlaced sets of singularities associated with a sequentially increasing number of ions

in the channel (Fig.3A).

Electrostatic blockade points correspond to minima in the ground state energy of the pore (Fig.3C). The points () are equivalent to neutralisation points[12] where .

Resonant conduction points correspond to the barrier-less condition: , or .

The values of [2] are given by the simple formulaei.e. the period of conductance oscillations in , .

For , in a typical ion channel geometry, , and ICB becomes strong. Consequently, plots of the BD-simulated current vs exhibit multi-ion conduction bands - strong Coulomb blockade oscillations between minima and maxima (Fig.3A)).[12]

The point corresponds to an uncharged pore with . Such pores are blockaded for ions of either sign.

Coulomb staircase

The ICB oscillations in conductance correspond to a Coulomb staircase in the pore occupancy , with transition regions corresponding to and saturation regions corresponding to (Fig.3B) . The shape of the staircase is described by the Fermi-Dirac (FD) distribution,[2] similarly to the Coulomb staircases of quantum dots.[5] Thus, for the transition, the FD function is: Here is the excess chemical potential for the particular ion and is an equivalent bulk occupancy related to pore volume. The saturated FD statistics of occupancy is equivalent to the Langmuir isotherm[19] or to Michaelis–Menten kinetics.[20]

It is the factor that gives rise to the concentration-related shift in the staircase seen in Fig.3B.

Shift of singular points

Addition of the partial excess chemical potentials coming from different sources (including dehydration,[15] local binding,[21] volume exclusion etc.[9][17]) leads to the ICB barrier-less condition leads to a proper shift in the ICB resonant points , described by a "shift equation" :[22][21] i.e. the additional energy contributions lead to shifts in the resonant barrier-less point .

The more important of these shifts (excess potentials) are:

- A concentration-related shift arising from the bulk entropy[17]

- A dehydration-related shift , arising from partial dehydration penalty [15]

- A local binding-related shift , coming from energy of local binding [21] and surface effects.[23]

In artificial nanopores

Sub-nm MoS2 pores

Following its prediction based on analytic theory[1][2] and molecular dynamics simulations, experimental evidence for ICB emerged from experiments[3] on monolayer pierced by a single nm nanopore. Highly non-Ohmic conduction was observed between aqueous ionic solutions on either side of the membrane. In particular, for low voltages across the membrane, the current remained close to zero, but it rose abruptly when a threshold of about mV was exceeded. This was interpreted as complete ionic Coulomb blockade of current in the (uncharged) nanopore due to the large potential barrier at low voltages. But the application of larger voltages pulled the barrier down, producing accessible states into which transitions could occur, thus leading to conduction.

In biological ion channels

The realisation that ICB could occur in biological ion channels[2] accounted for several experimentally observed features of selectivity, including:

Valence selectivity

Valence selectivity is the channel's ability to discriminate between ions of different valence , wherein e.g. a calcium channel favours ions over ions by a factor of up to 1000×.[24] Valence selectivity has been attributed variously to pure electrostatics,[11] or to a charge space competition mechanism,[25] or to a snug fit of the ion to ligands,[26] or to quantised dehydration.[27] In the ICB model, valence selectivity arises from electrostatics, namely from -dependence of the value of needed to provide for barrier-less conduction.

Correspondingly, the ICB model provides explanations of why site-directed mutations that alter can destroy the channel by blockading it, or can alter its selectivity from favouring ions to favouring ions, or vice versa [28].

Divalent blockade

Divalent (e.g. ) blockade of monovalent (e.g. ) currents is observed in some types of ion channels. Namely,[24] ions in a pure sodium solution pass unimpeded through a calcium channel, but are blocked by tiny (nM) extracellular concentrations of ions.[24] ICB provides a transparent explanation of both the phenomenon itself and of the Langmuir-isotherm-shape of the current vs. attenuation curve, deriving them from the strong affinity and an FD distribution of ions.[2][13] Vice versa, appearance divalent blockade presents strong evidence in favour of ICB

Similarly, ICB can account for the divalent (Iodide ) blockade that has been observed in biological chloride ()-selective channels.[14]

Special features

Comparisons between ICB and ECB

ICB and ECB should be considered as two versions of the same fundamental electrostatic phenomenon. Both ICB and ECB are based on charge quantisation and on the finite single-particle charging energy , resulting in close similarity of the governing equations and manifestations of these closely related phenomena. Nonetheless, there are important distinctions between ICB and ECB: their similarities and differences are summarised in Table 1.

| Property | ICB | ECB |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile charge carriers | cations ( etc...),

anions ( etc.) |

electrons () |

| Valence of mobile charge carriers, | positive (+1, +2, +3,...),

negative (-1, -2...) |

|

| Transport engine | Classical diffusion | QM tunneling |

| Conductance oscillations | Yes, valence dependent | Yes |

| Coulomb staircase for occupancy, | Yes, FD-shaped | Yes, FD-shaped |

Particular cases

Coulomb blockade can also appear in superconductors; in such a case the free charge carriers are Cooper pairs () [29]

In addition, Pauli spin blockade [30] represents a special kind of Coulomb blockade, connected with Pauli exclusion principle.

Quantum analogies

Despite appearing in completely classical systems, ICB exhibits some phenomena reminiscent of quantum-mechanics (QM). They arise because the charge/entity discreteness of the ions leads to quantisation of the energy spectrum and hence to the QM-analogies:[31]

- Noise-driven diffusive motion provides for escape over barriers, comparable to QM-tunnelling in ECB.

- The particular FD shape[2] of the occupancy vs plays a significant role in the ICB explanation of the divalent blockade phenomenon.[13] The appearance of an FD distribution in the diffusion of classical particles obeying an exclusion principle, has been demonstrated rigorously.[19][32][33]

See also

- Coulomb blockade

- Ion channel

- Brownian dynamics

- Nanopore

- Binding selectivity

- Fermi–Dirac statistics

- Electrostatics

- Quantisation of charge

- Elementary charge

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Krems, Matt; Di Ventra, Massimiliano (2013-01-10). "Ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 25 (6): 065101. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/25/6/065101. PMID 23307655. Bibcode: 2013JPCM...25f5101K.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Kaufman, Igor Kh; McClintock, Peter V E; Eisenberg, Robert S (2015). "Coulomb blockade model of permeation and selectivity in biological ion channels". New Journal of Physics 17 (8): 083021. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/17/8/083021. Bibcode: 2015NJPh...17h3021K.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Feng, Jiandong; Graf, Michael; Dumcenco, Dumitru; Kis, Andras; Di Ventra, Massimiliano; Radenovic, Aleksandra (2016). "Observation of ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores". Nature Materials 15 (8): 850–855. doi:10.1038/nmat4607. PMID 27019385. Bibcode: 2016NatMa..15..850F. http://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/217564.

- ↑ Averin, D. V.; Likharev, K. K. (1986-02-01). "Coulomb blockade of single-electron tunneling, and coherent oscillations in small tunnel junctions" (in en). Journal of Low Temperature Physics 62 (3–4): 345–373. doi:10.1007/bf00683469. ISSN 0022-2291. Bibcode: 1986JLTP...62..345A.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beenakker, C. W. J. (1991-07-15). "Theory of Coulomb-blockade oscillations in the conductance of a quantum dot". Physical Review B 44 (4): 1646–1656. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.44.1646. PMID 9999698. Bibcode: 1991PhRvB..44.1646B.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Eisenman, George; Horn, Richard (1983-10-01). "Ionic selectivity revisited: The role of kinetic and equilibrium processes in ion permeation through channels". The Journal of Membrane Biology 76 (3): 197–225. doi:10.1007/bf01870364. ISSN 0022-2631. PMID 6100862.

- ↑ von Kitzing, Eberhard (1992), "A Novel Model for Saturation of Ion Conductivity in Transmembrane Channels" (in en), Membrane Proteins: Structures, Interactions and Models, The Jerusalem Symposia on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry, 25, Springer Netherlands, pp. 297–314, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-2718-9_25, ISBN 9789401052054

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Zhang, J.; Kamenev, A.; Shklovskii, B. I. (2006-05-19). "Ion exchange phase transitions in water-filled channels with charged walls". Physical Review E 73 (5): 051205. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.051205. PMID 16802926. Bibcode: 2006PhRvE..73e1205Z.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Roux, Benot; Allen, Toby; Bernche, Simon; Im, Wonpil (2004-02-01). "Theoretical and computational models of biological ion channels". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 37 (1): 15–103. doi:10.1017/s0033583504003968. ISSN 0033-5835. PMID 17390604. Bibcode: 2004APS..MAR.J7004R. http://edoc.unibas.ch/1689/1/theoretical_and_computational_models_of_biological_ion_channels.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Yesylevskyy, S.O.; Kharkyanen, V.N. (2005-06-01). "Barrier-less knock-on conduction in ion channels: peculiarity or general mechanism?". Chemical Physics 312 (1–3): 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2004.11.031. ISSN 0301-0104. Bibcode: 2005CP....312..127Y.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Corry, Ben; Vora, Taira; Chung, Shin-Ho (June 2005). "Electrostatic basis of valence selectivity in cationic channels". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1711 (1): 72–86. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.03.002. ISSN 0005-2736. PMID 15904665.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Kaufman, I.; Luchinsky, D. G.; Tindjong, R.; McClintock, P. V. E.; Eisenberg, R. S. (2013-11-19). "Energetics of discrete selectivity bands and mutation-induced transitions in the calcium-sodium ion channels family". Physical Review E 88 (5): 052712. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.88.052712. PMID 24329301. Bibcode: 2013PhRvE..88e2712K.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Kaufman, Igor Kh.; Fedorenko, Olena A.; Luchinsky, Dmitri G.; Gibby, William A.T.; Roberts, Stephen K.; McClintock, Peter V.E.; Eisenberg, Robert S. (2017). "Ionic Coulomb blockade and anomalous mole fraction effect in the NaChBac bacterial ion channel and its charge-varied mutants" (in en). EPJ Nonlinear Biomedical Physics 5: 4. doi:10.1051/epjnbp/2017003. ISSN 2195-0008.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hartzell, Criss; Putzier, Ilva; Arreola, Jorge (2005-03-17). "Calcium -activated chloride channels" (in en). Annual Review of Physiology 67 (1): 719–758. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. ISSN 0066-4278. PMID 15709976.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Zwolak, Michael; Wilson, James; Ventra, Massimiliano Di (2010). "Dehydration and ionic conductance quantization in nanopores" (in en). Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 22 (45): 454126. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454126. ISSN 0953-8984. PMID 21152075. Bibcode: 2010JPCM...22S4126Z.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Landsberg, Peter T. (2014-03-05) (in en). Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486167589. https://books.google.com/books?id=NaQ-AwAAQBAJ&q=landsberg%20statistical%20mechanics%202014&pg=PP1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Krauss, Daniel; Eisenberg, Bob; Gillespie, Dirk (2011-03-06). "Selectivity sequences in a model calcium channel: role of electrostatic field strength" (in en). European Biophysics Journal 40 (6): 775–782. doi:10.1007/s00249-011-0691-6. ISSN 0175-7571. PMID 21380773.

- ↑ Nadler, Boaz; Hollerbach, Uwe; Eisenberg, R. S. (2003-08-13). "Dielectric boundary force and its crucial role in gramicidin". Physical Review E 68 (2): 021905. doi:10.1103/physreve.68.021905. ISSN 1063-651X. PMID 14525004. Bibcode: 2003PhRvE..68b1905N.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Fowler, R. H. (1935). "A Statistical Derivation of Langmuir's Adsorption Isotherm" (in en). Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 31 (2): 260–264. doi:10.1017/S0305004100013359. ISSN 1469-8064. Bibcode: 1935PCPS...31..260F.

- ↑ Ainsworth, Stanley (1977), "Michaelis-Menten Kinetics" (in en), Steady-State Enzyme Kinetics, Macmillan Education UK, pp. 43–73, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-01959-5_3, ISBN 9781349019618

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Kaufman, I.Kh.; Gibby W.A.T., Luchinsky D.G., McClintock P.V.E. (2017) (in en-US). Effect of local binding on stochastic transport in ion channels - IEEE Conference Publication. doi:10.1109/ICNF.2017.7985974.

- ↑ Luchinsky, D.G; Gibby W.A.T, Kaufman I.Kh., McClintock P.V.E., Timucin D.A. (2017) (in en-US). Relation between selectivity and conductivity in narrow ion channels - IEEE Conference Publication. doi:10.1109/ICNF.2017.7985973. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/88071/4/Luchinsky_Relation_between_selectivity_and_conductivity_icnf2017old.pdf.

- ↑ Tanaka, Hiroya; Iizuka, Hideo; Pershin, Yuriy V.; Ventra, Massimiliano Di (2018). "Surface effects on ionic Coulomb blockade in nanometer-size pores" (in en). Nanotechnology 29 (2): 025703. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/aa9a14. ISSN 0957-4484. PMID 29130892. Bibcode: 2018Nanot..29b5703T.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Sather, William A.; McCleskey, Edwin W. (2003). "Permeation and Selectivity in Calcium Channels" (in EN). Annual Review of Physiology 65 (1): 133–159. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142345. ISSN 0066-4278. PMID 12471162.

- ↑ Boda, Dezso; Nonner, Wolfgang; Henderson, Douglas; Eisenberg, Bob; Gillespie, Dirk (2008). "Volume exclusion in calcium selective channels". Biophysical Journal 94 (9): 3486–3496. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.122796. PMID 18199663. Bibcode: 2008BpJ....94.3486B.

- ↑ Dudev, Todor; Lim, Carmay (2014). "Evolution of eukaryotic ion Channels: principles underlying the conversion of Ca-selective to Na‑selective channels". Journal of the American Chemical Society 136 (9): 3553–559. doi:10.1021/ja4121132. PMID 24517213.

- ↑ Corry, Ben (2013). "Na/Ca selectivity in the bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel NavAb". Peer J 1: e16. doi:10.7717/peerj.16. PMID 23638350.

- ↑ Heinemann, Stefan H.; Terlau, Heinrich; Stühmer, Walter; Imoto, Keiji; Numa, Shosaku (1992). "Calcium channel characteristics conferred on the sodium channel by single mutations" (in En). Nature 356 (6368): 441–443. doi:10.1038/356441a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 1313551. Bibcode: 1992Natur.356..441H.

- ↑ Amar, A.; Song, D.; Lobb, C. J.; Wellstood, F. C. (1994-05-16). "2e to e periodic pair currents in superconducting Coulomb-blockade electrometers". Physical Review Letters 72 (20): 3234–3237. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.3234. PMID 10056141. Bibcode: 1994PhRvL..72.3234A.

- ↑ Danon, J.; Nazarov, Yu. V. (2009-07-01). "Pauli spin blockade in the presence of strong spin-orbit coupling". Physical Review B 80 (4): 041301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.041301. Bibcode: 2009PhRvB..80d1301D.

- ↑ Meyertholen, Andrew; Di Ventra, Massimiliano (2013-05-31). "Quantum Analogies in Ionic Transport Through Nanopores". arXiv:1305.7450 [cond-mat.mes-hall].

- ↑ Kaniadakis, G.; Quarati, P. (1993-12-01). "Kinetic equation for classical particles obeying an exclusion principle". Physical Review E 48 (6): 4263–4270. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.48.4263. PMID 9961106. Bibcode: 1993PhRvE..48.4263K.

- ↑ Kaniadakis, G.; Quarati, P. (1994-06-01). "Classical model of bosons and fermions". Physical Review E 49 (6): 5103–5110. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.49.5103. PMID 9961832. Bibcode: 1994PhRvE..49.5103K. https://cds.cern.ch/record/260481/files/P00022042.pdf.

|