Physics:Magnetic-tape data storage

| Computer memory types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| RAM |

| Historical |

|

| Non-volatile |

| ROM |

| NVRAM |

| Early stage NVRAM |

| Magnetic |

| Optical |

| In development |

| Historical |

|

Magnetic-tape data storage is a system for storing digital information on magnetic tape using digital recording. Commercial magnetic tape products used for data storage were first released in the 1950s and have continued to be developed and released to the present day.

Tape was an important medium for primary data storage in early computers, typically using large open reels of 7-track, later 9-track tape. Modern magnetic tape is most commonly packaged in cartridges and cassettes, such as the widely supported Linear Tape-Open (LTO)[1] and IBM 3592 series. The device that performs the writing or reading of data is called a tape drive. Autoloaders and tape libraries are often used to automate cartridge handling and exchange. Compatibility was important to enable transferring data.

Tape data storage[2] is now used more for system backup,[3] data archive and data exchange. The low cost of tape has kept it viable for long-term storage and archive.[4][5]

Usage

The earliest commercially available computers predate the existence of disk storage. Primary storage for these systems was done using tape.[6] The IBM 701, released in 1952, had the option of a 7-track tape drive, holding over a million characters (bytes) per reel. Drum storage was also available, but it was much lower capacity, holding around 9 thousand bytes, and it was not interchangeable. Years later and until disks became more affordable, mainframes could still be used with only tape storage, by running TOS/360 and its successors.

Looking beyond primary storage, writing data to tape on one computer and then reading it on another has long been a form of data interchange, predating modern data networks and the internet. This form of data transfer has been called Sneakernet. The high-bandwidth, high-latency nature of this is captured by an old, widely repeated quote:

Never underestimate the bandwidth of a station wagon full of tapes hurtling down the highway.—Andrew S. Tanenbaum & others, Sneakernet

Tape has long been used for making copies of data as part of an orderly backup process. While many other technologies are also used for backups, tape continues to be used for this, particularly at the largest scale.

Similarly, tape continues to see use as an archive for digital preservation efforts. With a low marginal unit cost and long lifespan, tape makes sense for many archiving scenarios.

Open reels

Initially, magnetic tape for data storage was wound on 10.5-inch (27 cm) reels.[7] This standard for large computer systems persisted through the late 1980s, with steadily increasing capacity due to thinner substrates and changes in encoding. Tape cartridges and cassettes were available starting in the mid-1970s and were frequently used with small computer systems. With the introduction of the IBM 3480 cartridge in 1984, described as "about one-fourth the size ... yet it stored up to 20 percent more data",[8] large computer systems started to move away from open-reel tapes and towards cartridges.[9]

UNIVAC

Magnetic tape was first used to record computer data in 1951 on the UNIVAC I.[10] The UNISERVO drive recording medium was a thin metal strip of 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) wide nickel-plated phosphor bronze. Recording density was 128 characters per inch (198 micrometres per character) on eight tracks at a linear speed of 100 in/s (2.54 m/s), yielding a data rate of 12,800 characters per second. Of the eight tracks, six were data, one was for parity, and one was a clock, or timing track. Making allowances for the empty space between tape blocks, the actual transfer rate was around 7,200 characters per second. A small reel of mylar tape provided separation between the metal tape and the read/write head.[11]

IBM formats

IBM computers from the 1950s used ferric-oxide-coated tape similar to that used in audio recording. IBM's technology soon became the de facto industry standard. Magnetic tape dimensions were 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) wide and wound on removable reels. Different tape lengths were available with 1,200 feet (370 m) and 2,400 feet (730 m) on mil and one half thickness being somewhat standard.[clarification needed] During the 1980s, longer tape lengths such as 3,600 feet (1,100 m) became available using a much thinner PET film. Most tape drives could support a maximum reel size of 10.5 inches (267 mm). A so-called mini-reel was common for smaller data sets, such as for software distribution. These were 7-inch (18 cm) reels, often with no fixed length—the tape was sized to fit the amount of data recorded on it as a cost-saving measure. CDC used IBM-compatible 1⁄2-inch (13 mm) magnetic tapes, but also offered a 1-inch-wide (25 mm) variant, with 14 tracks (12 data tracks corresponding to the 12-bit word of CDC 6000 series peripheral processors, plus 2 parity bits) in the CDC 626 drive.[12]

Early IBM tape drives, such as the IBM 727 and IBM 729, were mechanically sophisticated floor-standing drives that used vacuum columns to buffer long u-shaped loops of tape. Between servo control of powerful reel motors, a low-mass capstan drive, and the low-friction and controlled tension of the vacuum columns, fast start and stop of the tape at the tape-to-head interface could be achieved.[lower-alpha 1] The fast acceleration is possible because the tape mass in the vacuum columns is small; the length of tape buffered in the columns provides time to accelerate the high-inertia reels. When active, the two tape reels thus fed tape into or pulled tape out of the vacuum columns, intermittently spinning in rapid, unsynchronized bursts, resulting in visually striking action. Stock shots of such vacuum-column tape drives in motion were emblematically representative of computers in movies and television.[13]

Recording density increased over time. Common 7-track densities started at 200 characters per inch (CPI), then 556, and finally 800; 9-track tapes had densities of 800 (using NRZI), then 1600 (using PE), and finally 6250 (using GCR). This translates into about 5 megabytes to 140 megabytes per standard length (2,400 ft, 730 m) reel of tape. Effective density also increased as the interblock gap (inter-record gap) decreased from a nominal 3⁄4 inch (19 mm) on 7-track tape reel to a nominal 0.30 inches (7.6 mm) on a 6250 bpi[clarification needed] 9-track tape reel.[14]

At least partly due to the success of the System/360, and the resultant standardization on 8-bit character codes and byte addressing, 9-track tapes were very widely used throughout the computer industry during the 1970s and 1980s.[15] IBM discontinued new reel-to-reel products replacing them with cartridge based products beginning with its 1984 introduction of the cartridge-based 3480 family.

DEC format

LINCtape, and its derivative, DECtape were variations on this "round tape". They were essentially a personal storage medium,[16] used tape that was 0.75 inches (19 mm) wide and featured a fixed formatting track which, unlike standard tape, made it feasible to read and rewrite blocks repeatedly in place. LINCtapes and DECtapes had similar capacity and data transfer rate to the diskettes that displaced them, but their access times were on the order of thirty seconds to a minute.

Cartridges and cassettes

The IBM 7340 Hypertape drive, introduced in 1961, used a dual reel cassette with a 1-inch-wide (2.5 cm) tape capable of holding in excess of 40 million six-bit characters per cassette depending upon record length.[17]

In the 1970s and 1980s, audio Compact Cassettes were frequently used as an inexpensive data storage system for home computers,[lower-alpha 2] or in some cases for diagnostics or boot code for larger systems such as the Burroughs B1700.[19] Compact cassettes are logically, as well as physically, sequential; they must be rewound and read from the start to load data. Early cartridges were available before personal computers had affordable disk drives, and could be used as random access devices, automatically winding and positioning the tape, albeit with access times of many seconds.

In 2003 IBM introduced the 3592 family to supersede the IBM 3590. While the name is similar, there is no compatibility between the 3590 and the 3592. Like the 3590 and 3480 before it, this tape format has 1⁄2-inch (13 mm) tape spooled into a single reel cartridge. Initially introduced to support 300 gigabytes, the sixth generation released in 2018 supports a native capacity of 20 terabytes.[20]

Linear Tape-Open (LTO) single-reel cartridge was announced in 1997 at 100 gigabytes and in its eighth generation supports 12 terabytes in the same sized cartridge. As of 2019[update] LTO has completely displaced all other tape technologies in computer applications, with the exception of some IBM 3592 family at the high-end.

Technical details

Linear density

Bytes per inch (BPI) is the metric for the density at which data is stored on magnetic media. The term BPI can refer to bits per inch,[21] but more often refers to bytes per inch.[22]

The term BPI can mean bytes per inch when the tracks of a particular format are byte-organized, as in nine-track tapes.[23]

Tape width

The width of the media is the primary classification criterion for tape technologies. One-half-inch (13 mm) has historically been the most common width of tape for high-capacity data storage.[24] Many other sizes exist and most were developed to either have smaller packaging or higher capacity.[25]

Recording method

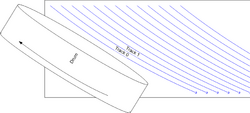

Linear

Scanning

Block layout and speed matching

Various methods have been used alone and in combination to cope with this difference. If the host cannot keep up with the tape drive transfer rate, the tape drive can be stopped, backed up, and restarted (known as shoe-shining). A large memory buffer can be used to queue the data. In the past, the host block size affected the data density on tape, but on modern drives, data is typically organized into fixed-sized blocks which may or may not be compressed or encrypted, and host block size no longer affects data density on tape. Modern tape drives offer a speed matching feature, where the drive can dynamically decrease the physical tape speed as needed to avoid shoe-shining.[26]

In the past, the size of the inter-block gap was constant, while the size of the data block was based on host block size, affecting tape capacity – for example, on count key data storage. On most modern drives, this is no longer the case. Linear Tape-Open type drives use a fixed-size block for tape (a fixed-block architecture), independent of the host block size, and the inter-block gap is variable to assist with speed matching during writes. On drives with compression, the compressibility of the data will affect the capacity.

Sequential access to data

Access time

Data compression

Most tape drives now include some kind of lossless data compression. There are several algorithms that provide similar results: LZW[citation needed] (widely supported), IDRC (Exabyte), ALDC (IBM, QIC) and DLZ1 (DLT).[citation needed] Embedded in tape drive hardware, these compress a relatively small buffer of data at a time, so cannot achieve extremely high compression even of highly redundant data. A ratio of 2:1 is typical, with some vendors claiming 2.6:1 or 3:1. The ratio actually obtained depends on the nature of the data so the compression ratio cannot be relied upon when specifying the capacity of equipment, e.g., a drive claiming a compressed capacity of 500 GB may not be adequate to back up 500 GB of real data. Data that is already stored efficiently may not allow any significant compression and a sparse database may offer much larger factors. Software compression can achieve much better results with sparse data, but uses the host computer's processor, and can slow the backup if the host computer is unable to compress as fast as the data is written.

Plain text, raw images, and database files (TXT, ASCII, BMP, DBF, etc.) typically compress much better than other types of data stored on computer systems. By contrast, encrypted data and pre-compressed data (PGP, ZIP, JPEG, MPEG, MP3, etc.) normally increase in size[lower-alpha 3] if data compression is applied. In some cases, this data expansion can be as much as 15%.

Encryption

Standards exist to encrypt tapes.[27] Encryption is used so that even if a tape is stolen, the thieves cannot use the data on the tape. Key management is crucial to maintain security. Compression is more efficient if done before encryption, as encrypted data cannot be compressed effectively due to the entropy it introduces. Some enterprise tape drives include hardware that can quickly encrypt data.[28]

Cartridge memory and self-identification

Some tape cartridges, notably LTO cartridges, have small associated data storage chips built in to record metadata about the tape, such as the type of encoding, the size of the storage, dates and other information. It is also common for tape cartridges to have bar codes on their labels in order to assist an automated tape library.[29]

Viability

Tape remains viable in modern data centers because:[30][31][32]

- it is the lowest cost medium for storing large amounts of data;

- as a removable medium it allows the creation of an air gap that can prevent data from being hacked, encrypted or deleted;

- its longevity allows for extended data retention which may be required by regulatory agencies.[33]

The lowest cost tiers of cloud storage can be supported by tape.[33]

Comparison to disk storage

Tape and disk storage have some important fundamental differences, which result in the technologies being used differently in practice.

One significant difference is how the raw media is packaged with or without the mechanism to use it. In disk storage, the hard disk drive platters that actually store the data are packaged together with the mechanism that reads and writes to it into a drive, while tape media is sold separately from the drive that reads and writes it. At scale, this has a large impact on cost, since expanding capacity does not require paying for additional mechanisms to use it. It also simplifies transporting and storing the storage media.

In recordable surface area, as of 2025, a current LTO cartridge contains about 20,000 square inches (13 m2) of surface area, while a current hard disk drive of similar capacity with 10 platters only has around 200 square inches (0.13 m2) of surface area, a factor of 100 difference. This dramatically affects seek time. Disks can generally return the first bytes requests within 10 ms, but tape can take over 100 sec, a factor of 10,000 difference.

Despite the slow seek time of tape, streaming throughput can be substantially faster than disk. While modern disk commonly have multiple read/write heads, only one operates at a time. Tape on the other hand, has long had multiple read/write heads that operate in parallel. Modern tape drives have 32 read/write elements, traversing the tape media at over 3 meters/sec.

Total costs get complicated when considering large storage systems. Besides the simple unit cost of the data storage media, there is the cost of the hardware that makes use of and manages the media and the cost of the power to run it all. As HDD prices have dropped, disk has become cheaper relative to tape drives and cartridges. For decades, the cost of a new LTO tape cartridge plus the tape drive required to make use of it, has been much greater than that of an equivalently sized HDD. However, at very large subsystem capacities, the total price of tape-based subsystems can be lower than HDD based subsystems, particularly when the higher operating costs of HDDs are included in any calculation.[34] Large robotic tape libraries are capable of managing hundreds of petabytes of data. Since most tapes in a library sit passively in their storage slot, the system uses relatively little power per TB stored. By contrast, disks must be kept powered on, spinning, and attached to some sort of computer system. The cost and capacity of storage arrays and tape libraries varies widely.

Disk generally has much lower initial costs, much better access times, and is better suited to online, interactive datasets which are more common in normal everyday usage. Tape generally has lower marginal costs and is more portable. These attributes make tape very appealing for large, primarily offline data sets, such as backups, archives, or an offline copy for protection against ransomware.[35]

High-density magnetic media

In 2002, Imation received a US$11.9 million grant from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology for research into increasing the data capacity of magnetic tape.[36]

In 2014, Sony and IBM announced that they had been able to record 148 gigabits per square inch with magnetic tape media developed using a new vacuum thin-film forming technology able to form extremely fine crystal particles, a tape storage technology with the highest reported magnetic tape data density, 148 Gbit/in² (23 Gbit/cm²), potentially allowing a native tape capacity of 185 TB.[37][38] It was further developed by Sony, with announcement in 2017, about reported data density of 201 Gbit/in² (31 Gbit/cm²), giving standard compressed tape capacity of 330 TB.[39]

In May 2014, Fujifilm followed Sony and made an announcement that it will develop a 154 TB tape cartridge in conjunction with IBM, which will have an areal data storage density of 85.9 GBit/in² (13.3 billion bits per cm²) on linear magnetic particulate tape.[40] The technology developed by Fujifilm, called NANOCUBIC, reduces the particulate volume of BaFe magnetic tape, simultaneously increasing the smoothness of the tape, increasing the signal to noise ratio during read and write while enabling high-frequency response. In December 2020, Fujifilm and IBM announced technology that could lead to a tape cassette with a capacity of 580 terabytes, using strontium ferrite as the recording medium.[41]

Chronological list of tape formats

- 1951: UNISERVO

- 1952: IBM 7-track

- 1958: TX-2 Tape System

- 1961: IBM 7340 Hypertape

- 1962: LINCtape

- 1963: DECtape

- 1964: 9-track

- 1964: Magnetic tape selectric typewriter

- 1972: Quarter-inch cartridge (QIC)

- 1975: KC standard, Compact Cassette

- 1976: DC100

- 1976: Compucolor Floppy Tape[42]

- 1977: Tarbell Cassette Interface

- 1977: Commodore Datasette

- 1979: DECtape II cartridge

- 1979: Exatron Stringy Floppy

- 1981: IBM PC Cassette Interface

- 1983: Sinclair ZX Microdrive

- 1984: Sinclair QL Microdrive

- 1984: Rotronics Wafadrive

- 1984: IBM 3480 cartridge

- 1984: Digital Linear Tape (DLT)

- 1986: SLR

- 1987: Data8

- 1989: Digital Data Storage (DDS) on Digital Audio Tape (DAT)

- 1992: Ampex DST

- 1994: Mammoth

- 1995: IBM 3590

- 1995: StorageTek Redwood SD-3

- 1995: Travan

- 1996: AIT

- 1997: IBM 3570 MP

- 1998: StorageTek T9840

- 1999: VXA

- 2000: StorageTek T9940

- 2000: LTO-1

- 2003: SAIT

- 2003: LTO-2

- 2003: 3592

- 2005: LTO-3

- 2005: TS1120

- 2006: T10000

- 2007: LTO-4

- 2008: TS1130

- 2008: T10000B

- 2010: LTO-5

- 2011: TS1140

- 2011: T10000C

- 2012: LTO-6

- 2013: T10000D

- 2014: TS1150

- 2015: LTO-7

- 2017: TS1155

- 2017: LTO-8

- 2018: TS1160

- 2021: LTO-9

- 2023: TS1170

- 2025: LTO-10

See also

- Computer data storage

- Data proliferation

- Information repository

- Linear Tape-Open

- Magnetic storage

- Tape drive

- Tape mark

Explanatory notes

- ↑ 1.5 ms from stopped tape to full speed of 112.5 inches per second (2.86 m/s).

- ↑ Experienced computer gamers could tell a lot by listening to the loading noise from the tape.[18]

- ↑ As illustrated by the pigeonhole principle, every lossless data compression algorithm will end up increasing the size of some inputs.

References

- ↑ "LTO Compliance-Verified Licencees". Ultrium. http://www.ultrium.com/newsite/html/licensing_certified.html.

- ↑ M. K. Roy; Debabrata Ghosh Dastidar (1989). Cobol Programming. p. 18. ISBN 0074603183. https://books.google.com/books?id=N066w1XgJXcC.

- ↑ "Ten Reasons Why Tape Is Still The Best Way To Backup Data". https://www.overlandstorage.com/blog/?p=323.

- ↑ Coughlin, Tom. "The Costs Of Storage" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomcoughlin/2016/07/24/the-costs-of-storage/.

- ↑ Lantz, Mark. "Why the Future of Data Storage is (Still) Magnetic Tape – IEEE Spectrum" (in en). https://spectrum.ieee.org/why-the-future-of-data-storage-is-still-magnetic-tape.

- ↑ "Magnetic tape | IBM". https://www.ibm.com/history/magnetic-tape.

- ↑ Clements, Alan (2013-01-01) (in en). Computer Organization & Architecture: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1285415420. https://books.google.com/books?id=ySILAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA698.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: IBM 3480 cartridge with standard tape reel". 23 January 2003. https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/storage/storage_PH3480B.html.

- ↑ "IBM 3480 tape cartridge (200 MB)". https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/memory-storage/8/258/1038. "... it replaced the standard ..."

- ↑ Staff, History Computer (2021-01-04). "Magnetic Tape Explained – Everything You Need To Know" (in en-US). https://history-computer.com/magnetic-tape/.

- ↑ "The Uniservo – Tape Reader and Recorder". American Federation of Information Processing Societies. 1952. https://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings/afips/1952/5041/00/50410047.pdf.

- ↑ Control Data 6400/6600 Computing Systems' Configurator. Control Data Corporation. October 1966. p. 4.

- ↑ "11 super high tech computers seen on 1960s television". https://www.metv.com/lists/11-super-high-tech-computers-seen-on-1960s-television.

- ↑ "IBM 3420 magnetic tape drive". IBM. 23 January 2003. https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/storage/storage_3420.html.

- ↑ "Obsolete Technology: Reel to Reel". Rice University. May 15, 2015. https://ricehistorycorner.com/2015/05/13/obsolete-technology-reel-to-reel/. "...became de rigueur on many different computers, from mainframes to minis."

- ↑ Bob Supnik (June 19, 2006). "Technical Notes on DECsys". http://simh.trailing-edge.com/docs/decsys.pdf.

- ↑ Cunningham, B.E.. "The IBM Hypertape system". ACM. pp. 423–434. doi:10.1145/1464052.1464089. ISBN 978-1-4503-7889-5. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/1464052.1464089. "The IBM Hypertape system was designed as a high-speed I/O device for the IBM 7074-7080-7090-7094 computers."

- ↑ Stuart, Keith (27 August 2019). "Click, whir, ping: the lost sounds of loading video games". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2019/aug/27/click-whir-ping-lost-sounds-of-loading-video-games.

- ↑ "B1700 Central System". 1973. p. 1-3, 2-97–. https://web.archive.org/web/20150422043547/http://bitsavers.trailing-edge.com/pdf/burroughs/B1700/1053360_B1700_FE_Tech_May73.pdf.

- ↑ Becca Caddy (Dec 13, 2022). "Magnetic tape: The surprisingly retro way big tech stores your data". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25634171-500-magnetic-tape-the-surprisingly-retro-way-big-tech-stores-your-data/.

- ↑ "BPI" (in en). Merriam-Webster, Inc.. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bpi.

- ↑ William F. Sharpe (1969). The Economics of Computers. p. 426. ISBN 0231083106. https://archive.org/details/economicsofcompu00shar.

- ↑ William F. Sharpe (1969). The Economics of Computers. p. 426. ISBN 0231083106. https://archive.org/details/economicsofcompu00will.

- ↑ "SDLT 320 handbook". http://downloads.quantum.com/sdlt320/handbook.pdf.

- ↑ "Magnetic Tape for Data" (in en-GB). https://obsoletemedia.org/data/tape/.

- ↑ "Info". www-01.ibm.com. http://www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=tss1wp102594&aid=1.

- ↑ "Tape Encryption Purchase Considerations". Oct 2007. http://www.computerweekly.com/feature/Tape-encryption-purchase-considerations.

- ↑ "Configuring tape drive encryption" (in en-us). https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/storage-protect/8.1.23?topic=methods-configuring-tape-drive-encryption.

- ↑ "LTO bar code label". https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/ts3500-tape-library?topic=media-lto-bar-code-label.

- ↑ "In the Tape vs. Disk War, Think Tape AND Disk – Enterprise Systems". Esj.com. 2009-02-17. Archived from the original on 2012-02-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20120201160318/http://esj.com/articles/2009/02/17/in-the-tape-vs-disk-war-think-tape-and-disk.aspx. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ↑ "HP article on backup for home users, recommending several methods, but not tape, 2011". H71036.www7.hp.com. 2010-03-25. Archived from the original on 2011-12-09. https://web.archive.org/web/20111209125241/http://h71036.www7.hp.com/hho/cache/565958-0-0-225-121.html. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ↑ "Oracle StorageTek SL8500 Modular Library System". https://www.oracle.com/storage/tape-storage/sl8500-modular-library-system.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "The role of tape in the modern data center". July 8, 2020. https://www.techradar.com/news/the-role-of-tape-in-the-modern-data-center. "Tape still offers several benefits that cloud storage doesn’t"

- ↑ "Disk vs Tape vs Cloud: What Archiving Strategy is Right for Your Business?". ProStorage. February 20, 2018. https://getprostorage.com/blog/disk-vs-tape-vs-cloud/.

- ↑ Schwartz, Karen D. (February 7, 2019). "Tape Storage Is 'Still Here'". ITPro Today. https://www.itprotoday.com/backup/tape-storage-still-here.

- ↑ "The Future of Tape: Containing the Information Explosion". https://www.datasafe.com/assets/downloads/articles/Tape_Data_Storage.pdf.

- ↑ "Sony develops magnetic tape technology with the world's highest*1 areal recording density of 148 Gb/in2". Sony Global. http://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/News/Press/201404/14-044E/index.html.

- ↑ Fingas, Jon (4 May 2014). "Sony's 185TB data tape puts your hard drive to shame". Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/2014/04/30/sony-185tb-data-tape/.

- ↑ "Sony Develops Magnetic Tape Storage Technology with the Industry's Highest*1 Recording Areal Density of 201 Gb/in2". Sony. https://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/News/Press/201708/17-070E/index.html.

- ↑ "Fujifilm achieves new data storage record of 154TB on advanced prototype tape". http://www.fujifilm.com/news/n140521.html.

- ↑ Grad, Peter. "Fujifilm, IBM unveil 580-terabyte magnetic tape" (in en). https://techxplore.com/news/2020-12-fujifilm-ibm-unveil-terabyte-magnetic.html.

- ↑ "Compucolor 8001 computer". www.oldcomputers.net. http://www.oldcomputers.net/compucolor-8001.html.

External links

- ISC 35.220.22 Magnetic Tapes

- ISC 35.220.23 Cassettes and cartridges for magnetic tapes

- Magnetic Tape Storage Technology, ACM Transactions on Storage, Volume 21, Issue 1, Lantz et al., 08 January 2025

- INSIC International Magnetic Tape Storage Technology Roadmap 2024, Information Storage Industry Consortium white paper, March 2024

|