Physics:Method of images

The method of images (or method of mirror images) is a mathematical tool for solving differential equations, in which boundary conditions are satisfied by combining a solution not restricted by the boundary conditions with its possibly weighted mirror image. Generally, original singularities are inside the domain of interest but the function is made to satisfy boundary conditions by placing additional singularities outside the domain of interest. Typically the locations of these additional singularities are determined as the virtual location of the original singularities as viewed in a mirror placed at the location of the boundary conditions. Most typically, the mirror is a hyperplane or hypersphere. The method of images can also be used in solving discrete problems with boundary conditions, such counting the number of restricted discrete random walks.

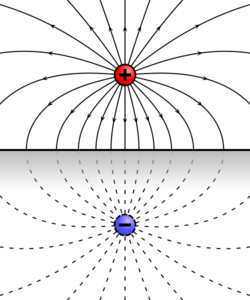

Method of image charges

The method of image charges is used in electrostatics to simply calculate or visualize the distribution of the electric field of a charge in the vicinity of a conducting surface. It is based on the fact that the tangential component of the electrical field on the surface of a conductor is zero, and that an electric field E in some region is uniquely defined by its normal component over the surface that confines this region (the uniqueness theorem).[1]

Magnet-superconductor systems

The method of images may also be used in magnetostatics for calculating the magnetic field of a magnet that is close to a superconducting surface. The superconductor in so-called Meissner state is an ideal diamagnet into which the magnetic field does not penetrate. Therefore, the normal component of the magnetic field on its surface should be zero. Then the image of the magnet should be mirrored. The force between the magnet and the superconducting surface is therefore repulsive.

Comparing to the case of the charge dipole above a flat conducting surface, the mirrored magnetization vector can be thought as due to an additional sign change of an axial vector.

In order to take into account the magnetic flux pinning phenomenon in type-II superconductors, the frozen mirror image method can be used.[2]

Mass transport in environmental flows with non-infinite domains

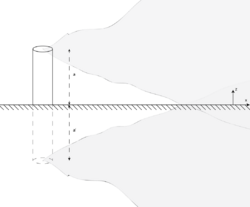

Environmental engineers are often interested in the reflection (and sometimes the absorption) of a contaminant plume off of an impenetrable (no-flux) boundary. A quick way to model this reflection is with the method of images.

The reflections, or images, are oriented in space such that they perfectly replace any mass (from the real plume) passing through a given boundary.[3] A single boundary will necessitate a single image. Two or more boundaries produce infinite images. However, for the purposes of modeling mass transport—such as the spread of a contaminant spill in a lake—it may be unnecessary to include an infinite set of images when there are multiple relevant boundaries. For example, to represent the reflection within a certain threshold of physical accuracy, one might choose to include only the primary and secondary images.

The simplest case is a single boundary in 1-dimensional space. In this case, only one image is possible. If as time elapses, a mass approaches the boundary, then an image can appropriately describe the reflection of that mass back across the boundary.

Another simple example is a single boundary in 2-dimensional space. Again, since there is only a single boundary, only one image is necessary. This describes a smokestack, whose effluent "reflects" in the atmosphere off of the impenetrable ground, and is otherwise approximately unbounded.

Finally, we consider a mass release in 1-dimensional space bounded to its left and right by impenetrable boundaries. There are two primary images, each replacing the mass of the original release reflecting through each boundary. There are two secondary images, each replacing the mass of one of the primary images flowing through the opposite boundary. There are also two tertiary images (replacing the mass lost by the secondary images), two quaternary images (replacing the mass lost by the tertiary images), and so on ad infinitum.

For a given system, once all of the images are carefully oriented, the concentration field is given by summing the mass releases (the true plume in addition to all of the images) within the specified boundaries. This concentration field is only physically accurate within the boundaries; the field outside the boundaries is non-physical and irrelevant for most engineering purposes.

Mathematics for continuous cases

This method is a specific application of Green's functions.[citation needed] The method of images works well when the boundary is a flat surface and the distribution has a geometric center. This allows for simple mirror-like reflection of the distribution to satisfy a variety of boundary conditions. Consider the simple 1D case illustrated in the graphic where there is a distribution of as a function of and a single boundary located at with the real domain such that and the image domain . Consider the solution to satisfy the linear differential equation for any , but not necessarily the boundary condition.

Note these distributions are typical in models that assume a Gaussian distribution. This is particularly common in environmental engineering, especially in atmospheric flows that use Gaussian plume models.

Perfectly reflecting boundary conditions

The mathematical statement of a perfectly reflecting boundary condition is as follows:

This states that the derivative of our scalar function will have no derivative in the normal direction to a wall. In the 1D case, this simplifies to:

This condition is enforced with positive images so that:[citation needed] where the translates and reflects the image into place. Taking the derivative with respect to :

Thus, the perfectly reflecting boundary condition is satisfied.

Perfectly absorbing boundary conditions

The statement of a perfectly absorbing boundary condition is as follows:[citation needed]

This condition is enforced using a negative mirror image:

And:

Thus this boundary condition is also satisfied.

Mathematics for discrete cases

The method of images can be used in discrete cases. For example, the number of random walks that start at position 0, take steps of size ±1, continue for a total of n steps, and end at position k is given by the binomial coefficient assuming that |k| ≤ n and n + k is even. Suppose we have the boundary condition that walks are prohibited from stepping to −1 during any part of the walk. The number of restricted walks can be calculated by starting with the number of unrestricted walks that start at position 0 and end at position k and subtracting the number of unrestricted walks that start at position −2 and end at position k. This is because, for any given number of steps, exactly as many unrestricted positively weighted walks as unrestricted negatively weighted walks will reach −1; they are mirror images of each other. As such, these negatively weighted walks cancel out precisely those positively weighted walks that our boundary condition has prohibited.

For example, if the number of steps is n = 2m and the final location is k = 0 then the number of restricted walks is the Catalan number

References

- ↑ *J. D. Jackson (1998). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-30932-1.

- ↑ Kordyuk, A. A. (1998). "Magnetic levitation for hard superconductors". Journal of Applied Physics 83 (1): 610–611. doi:10.1063/1.366648. Bibcode: 1998JAP....83..610K. http://www.imp.kiev.ua/~kord/papers/box/Kordyuk%20JAP%201998.pdf.

- ↑ "3.8 - Method of Images". http://web.mit.edu/fluids-modules/www/potential_flows/LecturesHTML/lec1011/node37.html.

|