Physics:Method of image charges

The method of image charges (also known as the method of images and method of mirror charges) is a basic problem-solving tool in electrostatics. The name originates from the replacement of certain elements in the original layout with fictitious charges, which replicates the boundary conditions of the problem (see Dirichlet boundary conditions or Neumann boundary conditions).

The validity of the method of image charges rests upon a corollary of the uniqueness theorem, which states that the electric potential in a volume V is uniquely determined if both the charge density throughout the region and the value of the electric potential on all boundaries are specified. Alternatively, application of this corollary to the differential form of Gauss' Law shows that in a volume V surrounded by conductors and containing a specified charge density ρ, the electric field is uniquely determined if the total charge on each conductor is given. Possessing knowledge of either the electric potential or the electric field and the corresponding boundary conditions we can swap the charge distribution we are considering for one with a configuration that is easier to analyze, so long as it satisfies Poisson's equation in the region of interest and assumes the correct values at the boundaries.[1]

Reflection in a conducting plane

Point charges

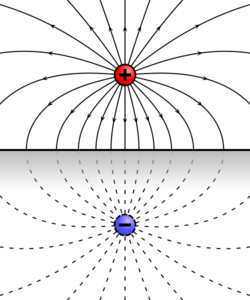

The simplest example of method of image charges is that of a point charge, with charge q, located at above an infinite grounded (i.e.: ) conducting plate in the xy-plane. To simplify this problem, we may replace the plate of equipotential with a charge −q, located at . This arrangement will produce the same electric field at any point for which (i.e., above the conducting plate), and satisfies the boundary condition that the potential along the plate must be zero. This situation is equivalent to the original setup, and so the force on the real charge can now be calculated with Coulomb's law between two point charges.[2]

The potential at any point in space, due to these two point charges of charge +q at +a and −q at −a on the z-axis, is given in cylindrical coordinates as

The surface charge density on the grounded plane is therefore given by

In addition, the total charge induced on the conducting plane will be the integral of the charge density over the entire plane, so:

The total charge induced on the plane turns out to be simply −q. This can also be seen from the Gauss's law, considering that the dipole field decreases at the cube of the distance at large distances, and the therefore total flux of the field though an infinitely large sphere vanishes.

Because electric fields satisfy the superposition principle, a conducting plane below multiple point charges can be replaced by the mirror images of each of the charges individually, with no other modifications necessary.

Electric dipole moments

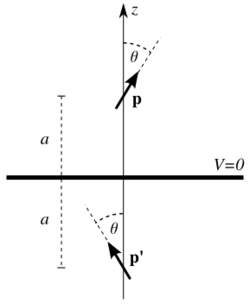

The image of an electric dipole moment p at above an infinite grounded conducting plane in the xy-plane is a dipole moment at with equal magnitude and direction rotated azimuthally by π. That is, a dipole moment with Cartesian components will have in image dipole moment . The dipole experiences a force in the z direction, given by

and a torque in the plane perpendicular to the dipole and the conducting plane,

Reflection in a dielectric planar interface

Similar to the conducting plane, the case of a planar interface between two different dielectric media can be considered. If a point charge is placed in the dielectric that has the dielectric constant , then the interface (with the dielectric that has the dielectric constant ) will develop a bound polarization charge. It can be shown that the resulting electric field inside the dielectric containing the particle is modified in a way that can be described by an image charge inside the other dielectric. Inside the other dielectric, however, the image charge is not present.[3]

Unlike the case of the metal, the image charge is not exactly opposite to the real charge: . It may not even have the same sign, if the charge is placed inside the stronger dielectric material (charges are repelled away from regions of lower dielectric constant). This can be seen from the formula.

Reflection in a conducting sphere

Point charges

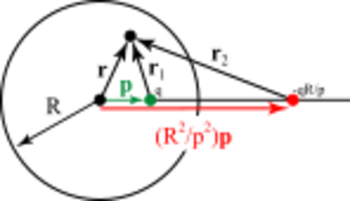

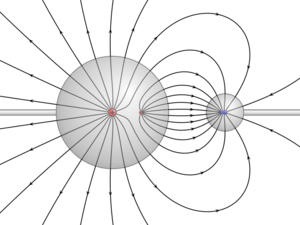

The method of images may be applied to a sphere as well.[4] In fact, the case of image charges in a plane is a special case of the case of images for a sphere. Referring to the figure, we wish to find the potential inside a grounded sphere of radius R, centered at the origin, due to a point charge inside the sphere at position (For the opposite case, the potential outside a sphere due to a charge outside the sphere, the method is applied in a similar way). In the figure, this is represented by the green point. Let q be the point charge of this point. The image of this charge with respect to the grounded sphere is shown in red. It has a charge of q′ = −qR/p and lies on a line connecting the center of the sphere and the inner charge at vector position . It can be seen that the potential at a point specified by radius vector due to both charges alone is given by the sum of the potentials:

Multiplying through on the rightmost expression yields:

and it can be seen that on the surface of the sphere (i.e. when r = R), the potential vanishes. The potential inside the sphere is thus given by the above expression for the potential of the two charges. This potential will not be valid outside the sphere, since the image charge does not actually exist, but is rather "standing in" for the surface charge densities induced on the sphere by the inner charge at . The potential outside the grounded sphere will be determined only by the distribution of charge outside the sphere and will be independent of the charge distribution inside the sphere. If we assume for simplicity (without loss of generality) that the inner charge lies on the z-axis, then the induced charge density will be simply a function of the polar angle θ and is given by:

The total charge on the sphere may be found by integrating over all angles:

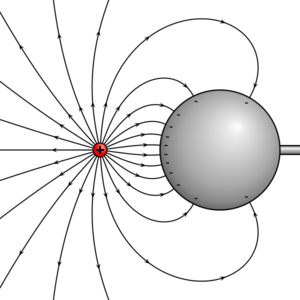

Note that the reciprocal problem is also solved by this method. If we have a charge q at vector position outside of a grounded sphere of radius R, the potential outside of the sphere is given by the sum of the potentials of the charge and its image charge inside the sphere. Just as in the first case, the image charge will have charge −qR/p and will be located at vector position . The potential inside the sphere will be dependent only upon the true charge distribution inside the sphere. Unlike the first case the integral will be of value −qR/p.

Electric dipole moments

The image of an electric point dipole is a bit more complicated. If the dipole is pictured as two large charges separated by a small distance, then the image of the dipole will not only have the charges modified by the above procedure, but the distance between them will be modified as well. Following the above procedure, it is found that a dipole with dipole moment at vector position lying inside the sphere of radius R will have an image located at vector position (i.e. the same as for the simple charge) and will have a simple charge of:

and a dipole moment of:

Method of inversion

The method of images for a sphere leads directly to the method of inversion.[5] If we have a harmonic function of position where are the spherical coordinates of the position, then the image of this harmonic function in a sphere of radius R about the origin will be

If the potential arises from a set of charges of magnitude at positions , then the image potential will be the result of a series of charges of magnitude at positions . It follows that if the potential arises from a charge density , then the image potential will be the result of a charge density .

See also

- Kelvin transform

- Coulomb's law

- Divergence theorem

- Flux

- Gaussian surface

- Schwarz reflection principle

- Uniqueness theorem for Poisson's equation

- Image antenna

- Surface equivalence principle

- Schottky effect

References

Notes

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (2013). Introduction to Electrodynamics (4th ed.). Pearson. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-321-85656-2.

- ↑ Jeans 1908, p. 186

- ↑ Jackson 1962, p. 111

- ↑ Tikhonov, Andrey N.; Samarskii, Alexander A. (1963). Equations of Mathematical Physics. New York: Dover Publications. p. 354. ISBN 0-486-66422-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=SLYXs2nW0PcC&pg=PA354.

- ↑ Jackson 1962, p. 35

Sources

- Jackson, John D. (1962). Classical Electrodynamics. John Wiley & Sons. https://archive.org/stream/ClassicalElectrodynamics/Jackson-ClassicalElectrodynamics.

- Jeans, James H. (1908). The Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism. Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/2mathematicalthe00jeanuoft.

Further reading

- Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1989). Feynman Lectures on Physics, Mainly Electromagnetism and Matter. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-51003-0.

- Landau, Lev D.; Lifshitz, Evgeny M.; Pitaevskii, Lev P. (1960). Electrodynamics of Continuous Media 2nd Edition. London: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-2634-7.

- Purcell, Edward M.. Berkeley Physics Course, Vol-2: Electricity and Magnetism (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

|