Physics:Ramsey interferometry

Ramsey interferometry, also known as the separated oscillating fields method,[1] is a form of particle interferometry that uses the phenomenon of magnetic resonance to measure transition frequencies of particles. It was developed in 1949 by Norman Ramsey,[2] who built upon the ideas of his mentor, Isidor Isaac Rabi, who initially developed a technique for measuring particle transition frequencies. Ramsey's method is used today in atomic clocks and in the S.I. definition of the second. Most precision atomic measurements, such as modern atom interferometers and quantum logic gates, have a Ramsey-type configuration.[3] A more modern method, known as Ramsey–Bordé interferometry uses a Ramsey configuration and was developed by French physicist Christian Bordé and is known as the Ramsey–Bordé interferometer. Bordé's main idea was to use atomic recoil to create a beam splitter of different geometries for an atom-wave. The Ramsey–Bordé interferometer specifically uses two pairs of counter-propagating interaction waves, and another method named the "photon-echo" uses two co-propagating pairs of interaction waves.[4][5]

Introduction

A main goal of precision spectroscopy of a two-level atom is to measure the absorption frequency between the ground state |↓⟩ and excited state |↑⟩ of the atom. One way to accomplish this measurement is to apply an external oscillating electromagnetic field at frequency and then find the difference (also known as the detuning) between and by measuring the probability to transfer |↓⟩ to |↑⟩ . This probability can be maximized when , when the driving field is on resonance with the transition frequency of the atom. Looking at this probability of transition as a function of the detuning , the narrower the peak around the more precision there is. If the peak were very broad about then it would be difficult to distinguish precisely where is located due to many values of having close to the same probability.[3]

Physical principles

The Rabi method

A simplified version of the Rabi method consists of a beam of atoms, all having the same speed and the same direction, sent through one interaction zone of length . The atoms are two-level atoms with a transition energy of (this is defined by applying a field in an excitation direction , and thus , the Larmor frequency), and with an interaction time of in the interaction zone. In the interaction zone, a monochromatic oscillating magnetic field labeled is applied perpendicular to the excitation direction, and this will lead to Rabi oscillations between |↓⟩ and |↑⟩ at a frequency of .[3][6]

The Hamiltonian in the rotating frame (including the rotating wave approximation) is:

The probability of transition from |↓⟩ and |↑⟩ can be found from this Hamiltonian and is

This probability will be at its maximum when . The line width of this vs. determines the precision of the measurement. Because , by increasing , or , and correspondingly decreasing so that their product is , the precision of the measurement increases; i.e. the peak of the graph becomes narrower.

In reality, however, inhomogeneities such as the atoms having a distribution of velocities or there being an inhomogeneous will cause the line shape to broaden and lead to decreased precision. Having a distribution of velocities means having a distribution of interaction times, and therefore there would be many angles through which state vectors would flip on the Bloch sphere. There would be an optimal length in the Rabi setup that would give the greatest precision, but it would not be possible to increase the length ad infinitum and expect ever increasing precision, as was the case in the perfect, simple Rabi model.[3]

The Ramsey method

Ramsey improved upon Rabi's method by splitting the one interaction zone into two very short interaction zones, each applying a pulse. The two interaction zones are separated by a much longer non-interaction zone. By making the two interaction zones very short, the atoms spend a much shorter time in the presence of the external electromagnetic fields than they would in the Rabi model. This is advantageous because the longer the atoms are in the interaction zone, the more inhomogeneities (such as an inhomogeneous field) lead to reduced precision in determining . The non-interaction zone in Ramsey's model can be made much longer than the one interaction zone in Rabi's method because there is no perpendicular field being applied in the non-interaction zone (although there is still ).[2]

The primary improvement from the Ramsey method is because the main peak resonance frequency represents an average over the frequencies (and inhomogeneities) in the non-interaction region between the cavities, whereas with the Rabi method the inhomogeneities in the interaction region lead to line-broadening. An additional advantage of the Ramsey method for microwave or optical transitions is that the non-interaction region can be made much longer than an interaction region with the Rabi method resulting in narrower linewidths.

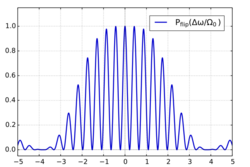

The Hamiltonian in the rotating frame for the two interaction zones is the same for that of the Rabi method, and in the non-interaction zone the Hamiltonian is only the term. First a pulse is applied to atoms in the ground state, whereupon the atoms reach the non-interaction zone and the spins precess about the z-axis for time . Another pulse is applied and the probability measured—practically this experiment must be done many times, because one measurement will not be enough to determine the probability of measuring any value. (See the Bloch Sphere description below). By applying this evolution to atoms of one velocity, the probability to find the atom in the excited state as a function of the detuning and time of flight in the non-interaction zone is (taking here)

This probability function describes the well-known Ramsey fringes.

If there is a distribution of velocities and a "hard pulse" is applied in the interaction zones so that all of the spins of the atoms are rotated on the Bloch sphere regardless of whether or not they all were excited to exactly the same resonance frequency, the Ramsey fringes will look very similar to those discussed above. If a hard pulse is not applied, then the variation in interaction times must be taken into account. What results are Ramsey fringes in an envelope in the shape of the Rabi method probability for atoms of one velocity. The line width of the fringes in this case is what determines the precision with which can be determined and is

By increasing the time of flight in the non-interaction zone, , or equivalently increasing the length of the non-interaction zone, the line width can be substantially improved, by a factor of 10 or more, over that of other methods.[1]

Because Ramsey's model allows for a longer observation time, one can more precisely determine . This is a statement of the time-energy uncertainty principle: the larger the uncertainty in the time domain, the smaller the uncertainty in the Energy domain, or equivalently the frequency domain. Thought of another way, if two waves of almost exactly the same frequency are superimposed upon each other, then it will be impossible to distinguish them if the resolution of our eyes is larger than the difference between the two waves. Only after a long period of time will the difference between two waves become large enough to differentiate the two.[3]

Early Ramsey interferometers used two interaction zones separated in space, but it is also possible to use two pulses separated in time, as long as the pulses are coherent. In the case of time-separated pulses, the longer the time between pulses, the more precise the measurement.[2]

Applications of the Ramsey interferometer

Atomic clocks and the SI definition of the second

An atomic clock is fundamentally an oscillator whose frequency is matched to that of an atomic transition of a two-level atom, . The oscillator is the parallel external electromagnetic field in the non-interaction zone of the Ramsey–Bordé interferometer. By measuring the transition rate from the excited to the ground state, one can tune the oscillator so that by finding the frequency that yields the maximum transition rate. Once the oscillator is tuned, the number of oscillations of the oscillator can be counted electronically to give a certain time interval (e.g. the SI second, which is 9,192,631,770 periods of a cesium-133 atom).[2]

Experiments of Serge Haroche

Serge Haroche won the 2012 Nobel Prize in physics (with David J. Wineland[7]) for work involving cavity quantum electrodynamics (QED) in which the research group used microwave-frequency photons to verify the quantum description of electromagnetic fields.[8] Essential to their experiments was the Ramsey interferometer, which they used to demonstrate the transfer of quantum coherence from one atom to another through interaction with a quantum mode in a cavity. The setup is similar to a regular Ramsey interferometer, with key differences being there is a quantum cavity in the non-interaction zone and the second interaction zone has its field phase shifted by some constant relative to the first interaction zone.

If one atom is sent into the setup in its ground state and passed through the first interaction zone, the state would become a superposition of ground and excited states , just as it would with a regular Ramsey interferometer. It then passes through the quantum cavity, which initially contains only a vacuum, and then is measured to be or . A second atom initially in is then sent through the cavity and then through the phase-shifted second Ramsey interaction zone. If the first atom is measured to be in , then the probability that the second atom is in depends on the amount of time between sending in the first and the second atoms. The fundamental reason for this is that if the first atom is measured to be in , then there is a single mode of the electromagnetic field within the cavity that will subsequently affect the measurement outcome of the second atom.[8]

The Ramsey–Bordé interferometer

Early interpretations of atom interferometers, including those of Ramsey, used a classical description of the motion of the atoms, but Bordé introduced an interpretation that used a quantum description of the motion of the atoms. Strictly speaking, the Ramsey interferometer is not an interferometer in real space because the fringe patterns develop due to changes of the pseudo-spin of the atom in the internal atomic space. However, an argument could be made for the Ramsey interferometer to be an interferometer in real space by thinking about the atomic movement quantumly—the fringes can be thought of as the result of the momentum kick imparted to the atoms by the detuning .[4]

The four traveling-wave interaction geometry

The problem that Bordé et al.[5] were trying to solve in 1984 was the averaging-out of Ramsey fringes of atoms whose transition frequencies were in the optical range. When this was the case, first-order Doppler shifts caused the Ramsey fringes to vanish because of the introduced spread in frequencies. Their solution was to have four Ramsey interaction zones instead of two, each zone consisting of a traveling wave but still applying a pulse. The first two waves both travel in the same direction, and the second two both travel in the direction opposite that of the first and second. There are two populations that result from the interaction of the atoms first with the first two zones and subsequently with the second two. The first population consists of atoms whose Doppler-induced de-phasing has cancelled, resulting in the familiar Ramsey fringes. The second consists of atoms whose Doppler-induced de-phasing has doubled and whose Ramsey fringes have completely disappeared (this is known as the "backward-stimulated photon echo", and its signal goes to zero after integrating over all velocities).

The interaction geometry of two pairs of counter-propagating waves that Bordé et al. introduced allows improved resolution of spectroscopy of frequencies in the optical range, such as those of Ca and I2.[5]

The interferometer

Specifically, however, the Ramsey–Bordé interferometer is an atom interferometer that uses this four-traveling-wave geometry and the phenomenon of atomic recoil.[9] In Bordé's notation, |a⟩ is the ground state and |b⟩ is the excited state. When an atom enters any of the four interaction zones, the wavefunction of the atom is divided into a superposition of two states, where each state is described by a specific energy and a specific momentum: |α,mα⟩, where α is either a or b. The quantum number mα is the number of light momentum quanta that have been exchanged from the initial momentum, where is the wavevector of the laser. This superposition is due to the energy and momentum exchanged between the laser and the atom in the interaction zones during the absorption/emission processes. Because there is initially one atom-wave, after the atom has passed through three zones it is in a superposition of eight different states before it reaches the final interaction zone.

Looking at the probability to transition to |b⟩ after the atom has passed through the fourth interaction zone, one would find dependence on the detuning in the form of Ramsey fringes, but due to the difference in two quantum mechanical paths. After integrating over all velocities, there are only two closed circuit quantum mechanical paths that do not integrate to zero, and those are the |a, 0⟩ and |b, –1⟩ path and the |a, 2⟩ and |b, 1⟩ path, which are the two paths that lead to intersections of the diagram at the fourth interaction zone. The atom-wave interferometer formed by either of these two paths leads to a phase difference that is dependent on both internal and external parameters, i.e. it is dependent on the physical distances by which the interaction zones are separated and on the internal state of the atom, as well as external applied fields. Another way to think about these interferometers in the traditional sense is that for each path there are two arms, each of which is denoted by the atomic state.

If an external field is applied to either rotate or accelerate the atoms, there will be a phase shift due to the induced de Broglie phase in each arm of the interferometer, and this will translate to a shift in the Ramsey fringes. In other words, the external field will change the momentum states, which will lead to a shift in the fringe pattern, which can be detected. As an example, apply the following Hamiltonian of an external field to rotate the atoms in the interferometer:

This Hamiltonian leads to a time evolution operator to first order in :

If is perpendicular to , then the round trip phase factor for one oscillation is given by , where is the length of the entire apparatus from the first interaction zone to the final interaction zone. This will yield a probability such that

where is the wavelength of the atomic two-level transition. This probability represents a shift from by a factor of

For a calcium atom on the Earth's surface that rotates at , using and looking at the transition, the shift in the fringes would be , which is a measurable effect.

A similar effect can be calculated for the shift in the Ramsey fringes caused by the acceleration of gravity. The shifts in the fringes will reverse direction if the directions of the lasers in the interaction zones are reversed, and the shift will cancel if standing waves are used.

The Ramsey–Bordé interferometer provides the potential for improved frequency measurements in the presence of external fields or rotations.[9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ramsey, Norman F. (June 15, 1950). "A Molecular Beam Resonance Method with Separated Oscillating Fields". Physical Review 78 (6): 695–699. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.78.695. Bibcode: 1950PhRv...78..695R. http://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.78.695. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Bransden, B. H.; Joachain, Charles Jean (2003). Physics of Atoms and Molecules. Pearson Education (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-5823-5692-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Deutsch, Ivan. Quantum Optics I, PHYS 566, at the University of New Mexico. Problem Set 3 and Solutions. Fall 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bordé, Christian J. Email Correspondance on December 8, 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bordé, Christian J.; Salomon, Ch.; Avrillier, S.; van Lerberghe, A.; Bréant, Ch.; Bassi, D.; Scoles, G. (October 1984). "Optical Ramsey fringes with traveling waves". Physical Review A 30 (4): 1836–1848. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.30.1836. Bibcode: 1984PhRvA..30.1836B. http://christian.j.borde.free.fr/Ramsey.pdf. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ Deutsch, Ivan. Quantum Optics I, PHYS 566, at the University of New Mexico. Lecture notes of Alec Landow. Fall 2013.

- ↑

"The 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics" (Press release). Nobel Media AB.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics for 2012 to Serge Haroche College de France and Ecole Normale Superieure, Paris, France and David J. Wineland National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and University of Colorado Boulder, CO, USA

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Deutsch, Ivan. Quantum Optics I, PHYS 566, at the University of New Mexico. Problem Set 7 and Solutions. Fall 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bordé, Christian J. (September 4, 1989). "Atomic interferometry with internal state labelling". Physics Letters A 140 (1–2): 10–12. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(89)90537-9. ISSN 0375-9601. Bibcode: 1989PhLA..140...10B. http://christian.j.borde.free.fr/PLA89.pdf. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

|