Physics:Bloch sphere

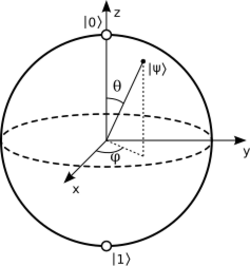

In quantum mechanics and computing, the Bloch sphere is a geometrical representation of the pure state space of a two-level quantum mechanical system (qubit), named after the physicist Felix Bloch.[1]

Quantum mechanics is mathematically formulated in Hilbert space or projective Hilbert space. The pure states of a quantum system correspond to the one-dimensional subspaces of the corresponding Hilbert space (and the "points" of the projective Hilbert space). For a two-dimensional Hilbert space, the space of all such states is the complex projective line This is the Bloch sphere, which can be mapped to the Riemann sphere.

The Bloch sphere is a unit 2-sphere, with antipodal points corresponding to a pair of mutually orthogonal state vectors. The north and south poles of the Bloch sphere are typically chosen to correspond to the standard basis vectors and , respectively, which in turn might correspond e.g. to the spin-up and spin-down states of an electron. This choice is arbitrary, however. The points on the surface of the sphere correspond to the pure states of the system, whereas the interior points correspond to the mixed states.[2][3] The Bloch sphere may be generalized to an n-level quantum system, but then the visualization is less useful.

For historical reasons, in optics the Bloch sphere is also known as the Poincaré sphere and specifically represents different types of polarizations. Six common polarization types exist and are called Jones vectors. Indeed Henri Poincaré was the first to suggest the use of this kind of geometrical representation at the end of 19th century,[4] as a three-dimensional representation of Stokes parameters.

The natural metric on the Bloch sphere is the Fubini–Study metric. The mapping from the unit 3-sphere in the two-dimensional state space to the Bloch sphere is the Hopf fibration, with each ray of spinors mapping to one point on the Bloch sphere.

Definition

Given an orthonormal basis, any pure state of a two-level quantum system can be written as a superposition of the basis vectors and , where the coefficient of (or contribution from) each of the two basis vectors is a complex number. This means that the state is described by four real numbers. However, only the relative phase between the coefficients of the two basis vectors has any physical meaning (the phase of the quantum system is not directly measurable), so that there is redundancy in this description. We can take the coefficient of to be real and non-negative. This allows the state to be described by only three real numbers, giving rise to the three dimensions of the Bloch sphere.

We also know from quantum mechanics that the total probability of the system has to be one:

- , or equivalently .

Given this constraint, we can write using the following representation:

- , where and .

The representation is always unique, because, even though the value of is not unique when is one of the states (see Bra-ket notation) or , the point represented by and is unique.

The parameters and , re-interpreted in spherical coordinates as respectively the colatitude with respect to the z-axis and the longitude with respect to the x-axis, specify a point

on the unit sphere in .

For mixed states, one considers the density operator. Any two-dimensional density operator ρ can be expanded using the identity I and the Hermitian, traceless Pauli matrices ,

- ,

where is called the Bloch vector.

It is this vector that indicates the point within the sphere that corresponds to a given mixed state. Specifically, as a basic feature of the Pauli vector, the eigenvalues of ρ are . Density operators must be positive-semidefinite, so it follows that .

For pure states, one then has

in comportance with the above.[5]

As a consequence, the surface of the Bloch sphere represents all the pure states of a two-dimensional quantum system, whereas the interior corresponds to all the mixed states.

u, v, w representation

The Bloch vector can be represented in the following basis, with reference to the density operator :[6]

where

This basis is often used in laser theory, where is known as the population inversion.[7] In this basis, the numbers are the expectations of the three Pauli matrices , allowing one to identify the three coordinates with x y and z axes.

Pure states

Consider an n-level quantum mechanical system. This system is described by an n-dimensional Hilbert space Hn. The pure state space is by definition the set of 1-dimensional rays of Hn.

Theorem. Let U(n) be the Lie group of unitary matrices of size n. Then the pure state space of Hn can be identified with the compact coset space

To prove this fact, note that there is a natural group action of U(n) on the set of states of Hn. This action is continuous and transitive on the pure states. For any state , the isotropy group of , (defined as the set of elements of U(n) such that ) is isomorphic to the product group

In linear algebra terms, this can be justified as follows. Any of U(n) that leaves invariant must have as an eigenvector. Since the corresponding eigenvalue must be a complex number of modulus 1, this gives the U(1) factor of the isotropy group. The other part of the isotropy group is parametrized by the unitary matrices on the orthogonal complement of , which is isomorphic to U(n − 1). From this the assertion of the theorem follows from basic facts about transitive group actions of compact groups.

The important fact to note above is that the unitary group acts transitively on pure states.

Now the (real) dimension of U(n) is n2. This is easy to see since the exponential map

is a local homeomorphism from the space of self-adjoint complex matrices to U(n). The space of self-adjoint complex matrices has real dimension n2.

Corollary. The real dimension of the pure state space of Hn is 2n − 2.

In fact,

Let us apply this to consider the real dimension of an m qubit quantum register. The corresponding Hilbert space has dimension 2m.

Corollary. The real dimension of the pure state space of an m-qubit quantum register is 2m+1 − 2.

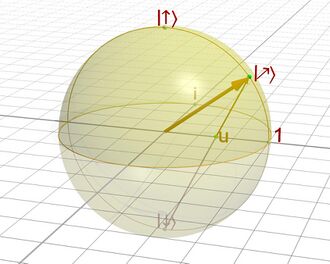

Plotting pure two-spinor states through stereographic projection

Given a pure state

where and are complex numbers which are normalized so that

and such that and , i.e., such that and form a basis and have diametrically opposite representations on the Bloch sphere, then let

be their ratio.

If the Bloch sphere is thought of as being embedded in with its center at the origin and with radius one, then the plane z = 0 (which intersects the Bloch sphere at a great circle; the sphere's equator, as it were) can be thought of as an Argand diagram. Plot point u in this plane — so that in it has coordinates .

Draw a straight line through u and through the point on the sphere that represents . (Let (0,0,1) represent and (0,0,−1) represent .) This line intersects the sphere at another point besides . (The only exception is when , i.e., when and .) Call this point P. Point u on the plane z = 0 is the stereographic projection of point P on the Bloch sphere. The vector with tail at the origin and tip at P is the direction in 3-D space corresponding to the spinor . The coordinates of P are

- .

Mathematically the Bloch sphere for a two-spinor state can be mapped to a Riemann sphere , i.e., the projective Hilbert space (as in case of finite-dimensional complex Hilbert spaces). The 2-dimensional complex Hilbert space is a representation space of SO(3).[8]

Density operators

Formulations of quantum mechanics in terms of pure states are adequate for isolated systems; in general quantum mechanical systems need to be described in terms of density operators. The Bloch sphere parametrizes not only pure states but mixed states for 2-level systems. The density operator describing the mixed-state of a 2-level quantum system (qubit) corresponds to a point inside the Bloch sphere with the following coordinates:

where is the probability of the individual states within the ensemble and are the coordinates of the individual states (on the surface of Bloch sphere). The set of all points on and inside the Bloch sphere is known as the Bloch ball.

For states of higher dimensions there is difficulty in extending this to mixed states. The topological description is complicated by the fact that the unitary group does not act transitively on density operators. The orbits moreover are extremely diverse as follows from the following observation:

Theorem. Suppose A is a density operator on an n level quantum mechanical system whose distinct eigenvalues are μ1, ..., μk with multiplicities n1, ..., nk. Then the group of unitary operators V such that V A V* = A is isomorphic (as a Lie group) to

In particular the orbit of A is isomorphic to

It is possible to generalize the construction of the Bloch ball to dimensions larger than 2, but the geometry of such a "Bloch body" is more complicated than that of a ball.[9]

Rotations

A useful advantage of the Bloch sphere representation is that the evolution of the qubit state is describable by rotations of the Bloch sphere. The most concise explanation for why this is the case is that the Lie algebra for the group of unitary and hermitian matrices is isomorphic to the Lie algebra of the group of three dimensional rotations .[10]

Rotation operators about the Bloch basis

The rotations of the Bloch sphere about the Cartesian axes in the Bloch basis are given by[11]

Rotations about a general axis

If is a real unit vector in three dimensions, the rotation of the Bloch sphere about this axis is given by:

An interesting thing to note is that this expression is identical under relabelling to the extended Euler formula for quaternions.

Derivation of the Bloch rotation generator

Ballentine[12] presents an intuitive derivation for the infinitesimal unitary transformation. This is important for understanding why the rotations of Bloch spheres are exponentials of linear combinations of Pauli matrices. Hence a brief treatment on this is given here. A more complete description in a quantum mechanical context can be found here.

Consider a family of unitary operators representing a rotation about some axis. Since the rotation has one degree of freedom, the operator acts on a field of scalars such that:

Where

We define the infinitesimal unitary as the Taylor expansion truncated at second order.

By the unitary condition:

Hence

For this equality to hold true (assuming is negligible) we require

- .

This results in a solution of the form:

Where is any Hermitian transformation, and is called the generator of the unitary family.

Hence:

Since the Pauli matrices are unitary Hermitian matrices and have eigenvectors corresponding to the Bloch basis, , we can naturally see how a rotation of the Bloch sphere about an arbitrary axis is described by

With the rotation generator given by

External links

See also

- Atomic electron transition

- Gyrovector space

- Poincaré sphere (optics)

- Versors

- Specific implementations of the Bloch sphere are enumerated under the qubit article.

References

- ↑ Bloch, Felix (Oct 1946). "Nuclear induction". Phys. Rev. 70 (7–8): 460–474. doi:10.1103/physrev.70.460. Bibcode: 1946PhRv...70..460B.; see Arecchi, F T, Courtens, E, Gilmore, R, & Thomas, H (1972). "Atomic coherent states in quantum optics", Phys Rev A6(6): 2211

- ↑ Nielsen, Michael A.; Chuang, Isaac L. (2004). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63503-5.

- ↑ "Bloch sphere | Quantiki". http://www.quantiki.org/wiki/Bloch_sphere.

- ↑ Poincaré, Henri (1892). Théorie mathématique de la lumière II. G. Carré. https://archive.org/details/thoriemathma00poin.

- ↑ The idempotent density matrix

- ↑ Feynman, Richard; Vernon, Frank; Hellwarth, Robert (January 1957). "Geometrical Representation of the Schrödinger Equation for Solving Maser Problems". Journal of Applied Physics 28 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1063/1.1722572. Bibcode: 1957JAP....28...49F.

- ↑ Milonni, Peter W.; Eberly, Joseph (1988). Lasers. New York: Wiley. p. 340. ISBN 978-0471627319.

- ↑ Penrose, Roger (2007). The Road to Reality : A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. New York: Vintage Books (Random House, Inc.). p. 554. ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4.

- ↑ Appleby, D.M. (2007). "Symmetric informationally complete measurements of arbitrary rank". Optics and Spectroscopy 103 (3): 416–428. doi:10.1134/S0030400X07090111. Bibcode: 2007OptSp.103..416A.

- ↑ D.B. Westra 2008, "SU(2) and SO(3)", https://www.mat.univie.ac.at/~westra/so3su2.pdf

- ↑ Nielsen and Chuang 2010, "Quantum Computation and Information," pg 174

- ↑ Ballentine 2014, "Quantum Mechanics - A Modern Development", Chapter 3

|