Physics:SCMaglev

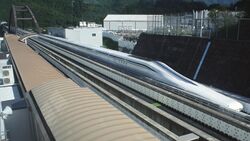

The SCMaglev (superconducting maglev, formerly called the MLU) is a magnetic levitation (maglev) railway system developed by Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central) and the Railway Technical Research Institute.[1][2][3]

On 21 April 2015, a manned seven-car L0 Series SCMaglev train reached a speed of 603 km/h (375 mph), less than a week after the same train clocked 590 km/h (370 mph), breaking the previous land speed record for rail vehicles of 581 km/h (361 mph) set by a JR Central MLX01 maglev train in December 2003.[4]

Technology

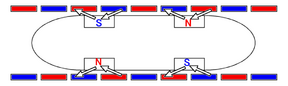

The SCMaglev system uses an electrodynamic suspension (EDS) system. The trains' bogies have superconducting magnets installed, and the guideways contain two sets of metal coils. The current levitation system utilizes a series of coils wound into a "figure 8" along both walls of the guideway. These coils are also cross-connected underneath the track.[3]

As the train accelerates, the magnetic fields of its superconducting magnets induce a current into these coils due to the magnetic field induction effect. If the train were centered with the coils, the electrical potential would be balanced and no currents would be induced. However, as the train runs on rubber wheels at relatively low speeds, the magnetic fields are positioned below the center of the coils, causing the electrical potential to no longer be balanced. This creates a reactive magnetic field opposing the superconducting magnet's pole (in accordance with Lenz's law), and a pole above that attracts it. Once the train reaches 150 km/h (93 mph), there is sufficient current flowing to lift the train 100 mm (4 in) above the guideway.[3]

These coils also generate guiding and stabilizing forces. Because they are cross-connected underneath the guideway, if the train moves off-center, currents are induced into the connections that correct its positioning.[3] SCMaglev also utilizes a linear synchronous motor (LSM) propulsion system, which powers a second set of coils in the guideway.

History

Japanese National Railways (JNR) began research on a linear propulsion railway system in 1962 with the goal of developing a train that could travel between Tokyo and Osaka in one hour.[5] Shortly after Brookhaven National Laboratory patented superconducting magnetic levitation technology in the United States in 1969, JNR announced development of its own superconducting maglev (SCMaglev) system. The railway made its first successful SCMaglev run on a short track at its Railway Technical Research Institute in 1972.[6] JR Central plans on exporting the technology, pitching it to potential buyers.[7]

Miyazaki test track

In 1977, SCMaglev testing moved to a new 7 km test track in Hyūga, Miyazaki. By 1980, the track was modified from a "reverse-T" shape to the "U" shape used today. In April 1987, JNR was privatized, and Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central) took over SCMaglev development.

In 1989, JR Central decided to build a better testing facility with tunnels, steeper gradients, and curves.[6] After the company moved maglev tests to the new facility, the company's Railway Technical Research Institute began to allow testing of ground effect trains, an alternate technology based on aerodynamic interaction between the train and the ground, at the Miyazaki Test Track in 1999.[citation needed]

Yamanashi maglev test line

Construction of the Yamanashi maglev test line began in 1990. The 18.4 km (11.4 mi) "priority section" of the line in Tsuru, Yamanashi, opened in 1997. MLX01 trains were tested there from 1997 to fall 2011, when the facility was closed to extend the line to 42.8 km (26.6 mi) and to upgrade it to commercial specifications.[8]

Commercial use

Japan

In 2009, Japan's Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism decided that the SCMaglev system was ready for commercial operation. In 2011, the ministry gave JR Central permission to operate the SCMaglev system on their planned Chūō Shinkansen linking Tokyo and Nagoya by 2027, and to Osaka by 2037. Construction is currently underway.

United States

Since 2010, JR Central has promoted the SCMaglev system in international markets, particularly the Northeast Corridor of the United States, as the Northeast Maglev.[1] In 2013, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe met with the 44th U.S. President Barack Obama and offered to provide the first portion of the SC Maglev track free, a distance of approximately 40 miles.[9] In 2016, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded $27.8 million to the Maryland Department of Transportation to prepare preliminary engineering and NEPA analysis for an SCMaglev train between Baltimore, MD, and Washington, DC.[10]

Australia

In late 2015, JR Central partnered with Mitsui and General Electric in Australia to form a joint venture named Consolidated Land and Rail Australia to provide a commercial funding model using private investors that could build the SC Maglev (linking Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne), create 8 new self-sustaining inland cities linked to the high speed connection, and contribute to the community.[11][12]

Vehicles

- 1972 – LSM200

- 1972 – ML100

- 1975 – ML100A

- 1977 – ML500

- 1979 – ML500R (remodeled ML500)

- 1980 – MLU001

- 1987 – MLU002

- 1993 – MLU002N

- 1995 – MLX01 (MLX01-1, 11, 2)

- 1997 – MLX01 (MLX01-3, 21, 12, 4)

- 2002 – MLX01 (MLX01-901, 22)

- 2009 – MLX01 (MLX01-901A, 22A: remodeled 901 and 22)

- 2013 – L0 Series Shinkansen

- 2020 – Revised L0 Series Shinkansen

| No. | Type | Note | Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLX01-1 | Kōfu-end car with double-cusp head | Displayed at the SCMaglev and Railway Park | 1995 |

| MLX01-11 | Standard intermediate car | ||

| MLX01-2 | Tokyo-end car with aero-wedge head | ||

| MLX01-3 | Kōfu-end car with aero-wedge head | Displayed at the Railway Technical Research Institute | 1997 |

| MLX01-21 | Long intermediate car | ||

| MLX01-12 | Standard intermediate car | ||

| MLX01-4 | Tokyo-end car with double-cusp head | ||

| MLX01-901A | Kōfu-end car with long head | Remodeled and renamed from MLX01-901 in 2009 | 2002 |

| MLX01-22A | long intermediate car | Remodeled and renamed from MLX01-22 in 2009 |

Records

Manned records

| Speed [km/h (mph)] | Train | Type | Location | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 (37) | ML100 | Maglev | RTRI of JNR | 1972 | |

| 400.8 (249.0) | MLU001 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | February 1987 | Two-car train set. Former world speed record for maglev trains. |

| 394.3 (245.0) | MLU002 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | November 1989 | Single-car |

| 411 (255) | MLU002N | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | February 1995 | Single-car |

| 531 (330) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line, Japan | 12 December 1997 | Three-car train set. Former world speed record for maglev trains. |

| 552 (343) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 14 April 1999 | Five-car train set. Former world speed record for maglev trains. |

| 581 (361) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 2 December 2003 | Three-car train set. Former world speed record for all trains. |

| 590 (367) | L0 series | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 16 April 2015 | Seven-car train set.[13] Former world speed record for all trains. |

| 603 (375) | L0 series | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 21 April 2015 | Seven-car train set. Current world speed record for all trains.[4] |

Unmanned records

| Speed [km/h (mph)] | Train | Type | Location | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 504 (313.2) | ML-500 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | 12 December 1979 | |

| 517 (321.2) | ML-500 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | 21 December 1979 | |

| 352.4 (219.0) | MLU001 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | January 1986 | Three-car train set |

| 405.3 (251.8) | MLU001 | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | January 1987 | Two-car train set |

| 431 (267.8) | MLU002N | Maglev | Miyazaki Maglev Test Track | February 1994 | Single-car |

| 550 (341.8) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 24 December 1997 | Three-car train set |

| 548 (340.5) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 18 March 1999 | Five-car train set |

Relative passing speed records

| Speed [km/h (mph)] | Train | Type | Location | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 966 (600) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | December 1998 | Former world relative passing speed record |

| 1,003 (623) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | November 1999 | Former world relative passing speed record |

| 1,026 (638) | MLX01 | Maglev | Yamanashi Maglev Test Line | 16 November 2004 | Current world relative passing speed record |

See also

- MAGLEV 2000

- Transrapid

- Krauss-Maffei Transurban - Electromagnetic suspension technology had been transferred from Krauss-Maffei.

- ROMAG

- Inductrack

References

- Hood, Christopher P. (2006). Shinkansen – From Bullet Train to Symbol of Modern Japan. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32052-6.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Central Japan Railway Company (11 May 2010). Test Ride of Superconducting Maglev by the US Secretary of Transportation, Mr. Ray LaHood. http://english.jr-central.co.jp/company/company/others/high-speed-rail/high-speed-rail.html.

- ↑ Central Japan Railway Company (2012). "Central Japan Railway Company Annual Report 2012". pp. 23–25. http://english.jr-central.co.jp/company/ir/annualreport/_pdf/annualreport2012.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 He, J.L.; Rote, D.M.; Coffey, H.T. (1994). "Study of Japanese Electrodynamic-Suspension Maglev Systems". NASA Sti/Recon Technical Report N (Argonne National Laboratory) 94: 37515. doi:10.2172/10150166. Bibcode: 1994STIN...9437515H. http://www.osti.gov/scitech/servlets/purl/10150166.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McCurry, Justin (21 April 2015). "Japan's Maglev Train Breaks World Speed Record with 600 km/h Test Run". The Guardian (New York). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/21/japans-maglev-train-notches-up-new-world-speed-record-in-test-run.

- ↑ The airline distance between Tokyo and Osaka is 397 kilometres (247 mi). To achieve an average speed of 397 km/h, such a train would need to be capable of speeds in excess of 500 km/h to allow for acceleration and deceleration times, intermediate stops, and additional distance incurred by a land route.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 U.S.-Japan Maglev (2012). "History". USJMAGLEV. http://usjmaglev.com/usjmaglev/History.html.

- ↑ "Japanese rail company eyes exports to cover maglev costs". https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Japanese-rail-company-eyes-exports-to-cover-maglev-costs.

- ↑ Central Japan Railway Company (2012). "The Chuo Shinkansen Using the Superconducting Maglev System". Data Book 2012. pp. 24–25. http://english.jr-central.co.jp/company/company/others/data-book/_pdf/2012.pdf.

- ↑ Pfanner, Eric (19 November 2013). "Japan Pitches Its High-Speed Train With an Offer to Finance". The New York Times: p. B8. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/19/business/international/japan-pitches-americans-on-its-maglev-train.html.

- ↑ "Baltimore-Washington Superconducting Maglev Project - Background". http://bwmaglev.info/index.php/overview/background.

- ↑ "General Electric, Japan Rail and Mitsui all aboard high-speed rail proposal" (in en-US). 2016-05-12. http://www.afr.com/brand/rear-window/general-electric-japan-rail-and-mitsui-all-aboard-highspeed-rail-proposal-20160512-gotq5d.

- ↑ "Consolidated Land and Rail Australia Pty Ltd". http://www.clara.com.au.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Sankei News. Japan: The Sankei Shimbun & Sankei Digital. 16 April 2015. http://www.sankei.com/economy/news/150416/ecn1504160038-n1.html.

Further reading

- Heller, Arnie (June 1998). "A New Approach for Magnetically Levitating Trains—and Rockets". Science & Technology Review. http://www.llnl.gov/str/Post.html.

- Henry H. Kolm; Richard D. Thornton (October 1973). "Electromagnetic Flight". Scientific American (Springer Nature) 229 (4): 17–25. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1073-17. Bibcode: 1973SciAm.229d..17K.

External links

- SCMAGLEV Website

- Central Japan Railway Company SCMAGLEV Official Website

- Railway Technical Research Institute (RTRI)

- RTRI Maglev website

- The Northeast Maglev

- SCMaglev trains

- U.S.-Japan MAGLEV

- Project information by The International Maglev Board

[ ⚑ ] 35°35′N 138°56′E / 35.583°N 138.933°E