Physics:Third-order intercept point

In telecommunications, a third-order intercept point (IP3 or TOI) is a specific figure of merit associated with the more general third-order intermodulation distortion (IMD3), which is a measure for weakly nonlinear systems and devices, for example receivers, linear amplifiers and mixers. It is based on the idea that the device nonlinearity can be modeled using a low-order polynomial, derived by means of Taylor series expansion. The third-order intercept point relates nonlinear products caused by the third-order nonlinear term to the linearly amplified signal, in contrast to the second-order intercept point that uses second-order terms.

The intercept point is a purely mathematical concept and does not correspond to a practically occurring physical power level. In many cases, it lies far beyond the damage threshold of the device.

Definitions

Two different definitions for intercept points are in use:

- Based on harmonics: The device is tested using a single input tone. The nonlinear products caused by n-th-order nonlinearity appear at n times the frequency of the input tone.

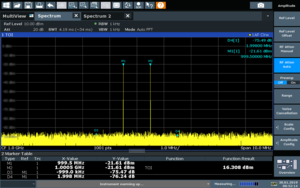

- Based on intermodulation products: The device is fed with two sine tones one at and one at . When you cube the sum of these sine waves you will get sine waves at various frequencies including and . If and are large but very close together then and will be very close to and . This two-tone approach has the advantage that it is not restricted to broadband devices and is commonly used for radio receivers.

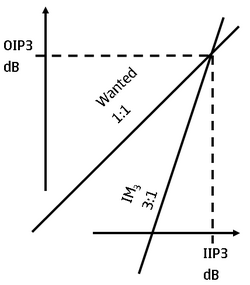

The intercept point is obtained graphically by plotting the output power versus the input power both on logarithmic scales (e.g., decibels). Two curves are drawn; one for the linearly amplified signal at an input tone frequency, one for a nonlinear product. On a logarithmic scale, the function xn translates into a straight line with slope of n. Therefore, the linearly amplified signal will exhibit a slope of 1. A third-order nonlinear product will increase by 3 dB in power when the input power is raised by 1 dB.

Both curves are extended with straight lines of slope 1 and n (3 for a third-order intercept point). The point where the curves intersect is the intercept point. It can be read off from the input or output power axis, leading to input (IIP3) or output (OIP3) intercept point respectively.

Input and output intercept point differ by the small-signal gain of the device.

Practical considerations

The concept of intercept point is based on the assumption of a weakly nonlinear system, meaning that higher-order nonlinear terms are small enough to be negligible. In practice, the weakly nonlinear assumption may not hold for the upper end of the input power range, be it during measurement or during use of the amplifier. As a consequence, measured or simulated data will deviate from the ideal slope of n. The intercept point according to its basic definition should be determined by drawing the straight lines with slope 1 and n through the measured data at the smallest possible power level (possibly limited towards lower power levels by instrument or device noise). It is a frequent mistake to derive intercept points by either changing the slope of the straight lines, or fitting them to points measured at too high power levels. In certain situations such a measure can be useful, but it is not an intercept point according to definition. Its value depends on the measurement conditions that need to be documented, whereas the IP according to definition is mostly unambiguous; although there is some dependency on frequency and tone spacing, depending on the physics of the device under test.

One of the useful applications of third-order intercept point is as a rule-of-thumb measure to estimate nonlinear products. When comparing systems or devices for linearity, a higher intercept point is better. It can be seen that the spacing between two straight lines with slopes of 3 and 1 closes with slope 2.

For example, assume a device with an input-referred third-order intercept point of 10 dBm is driven with a test signal of −5 dBm. This power is 15 dB below the intercept point, therefore nonlinear products will appear at approximately 2×15 dB below the test signal power at the device output (in other words, 3×15 dB below the output-referred third-order intercept point).

A rule of thumb that holds for many linear radio-frequency amplifiers is that the 1 dB compression point point falls approximately 10 dB below the third-order intercept point.

Theory

The third-order intercept point (TOI) is a property of the device transfer function O (see diagram). This transfer function relates the output signal voltage level to the input signal voltage level. We assume a "linear" device having a transfer function whose small-signal form may be expressed in terms of a power series containing only odd terms, making the transfer function an odd function of input signal voltage, i.e., O(−s) = −O(s). Where the signals passing through the actual device are modulated sinusoidal voltage waveforms (e.g., RF amplifier), device nonlinearities can be expressed in terms of how they affect individual sinusoidal signal components. For example, say the input voltage signal is the sine wave

and the device transfer function produces an output of the form

where G is the amplifier gain, and D3 is cubic distortion. We may substitute the first equation into the second and, using the trigonometric identity

we obtain the device output voltage waveform as

The output waveform contains the original waveform, cos(ωt), plus a new harmonic term, cos(3ωt), the third-order term. The coefficient of the cos(ωt) harmonic has two terms, one that varies linearly with V and one that varies with the cube of V. In fact, the coefficient of cos(ωt) has nearly the same form as the transfer function, except for the factor 3/4 on the cubic term. In other words, as signal level V is increased, the level of the cos(ωt) term in the output eventually levels off, similar to how the transfer function levels off. Of course, the coefficients of the higher-order harmonics will increase (with increasing V) as the coefficient of the cos(ωt) term levels off (the power has to go somewhere).

If we now restrict our attention to the portion of the cos(ωt) coefficient that varies linearly with V, and then ask ourselves, at what input voltage level V will the coefficients of the first- and third-order terms have equal magnitudes (i.e., where the magnitudes intersect), we find that this happens when

which is the third-order intercept point (TOI). So, we see that the TOI input power level is simply 4/3 times the ratio of the gain and the cubic distortion term in the device transfer function. The smaller the cubic term is in relation to the gain, the more linear the device is, and the higher the TOI is. The TOI, being related to the magnitude squared of the input voltage waveform, is a power quantity, typically measured in milliwatts (mW). The TOI is always beyond operational power levels because the output power saturates before reaching this level.

The TOI is closely related to the amplifier's "1 dB compression point", which is defined as that point at which the total coefficient of the cos(ωt) term is 1 dB below the linear portion of that coefficient. We can relate the 1 dB compression point to the TOI as follows. Since 1 dB = 20 log10 1.122, we may say, in a voltage sense, that the 1 dB compression point occurs when

or

or

In a power sense (V2 is a power quantity), a factor of 0.10875 corresponds to −9.636 dB, so by this approximate analysis, the 1 dB compression point occurs roughly 9.6 dB below the TOI.

Recall: decibel figure = 10 dB × log10(power ratio) = 20 dB × log10(voltage ratio).

See also

Notes

- The third-order intercept point is an extrapolated convergence – not directly measurable – of intermodulation distortion products in the desired output.

- It indicates how well a device (for example an amplifier) or a system (for example, a receiver) performs in the presence of strong signals.

- It is sometimes used (interchangeably with the 1 dB compression point) to define the upper limit of the dynamic range of an amplifier.

- Determination of a third-order intercept point of a superheterodyne receiver is accomplished by using two test frequencies that fall within the first intermediate frequency mixer passband. Usually, the test frequencies are about 20–30 kHz apart.

- The concept of intercept point has no meaning for strongly nonlinear systems, such as when an output signal is clipped due to limited supply voltage.

References

Further reading

- "Chapter 7: Class-A Amplifiers and Linearity". RF Circuit Design: Understanding RF Power Amplifiers (2 ed.). 2008-01-21. http://www.rfdesignline.com/howto/205800662.

- "The Relationship of Intercept Points and Composite Distortions". Matrix Test Equipment, Inc.. 2018-02-18. http://www.matrixtest.com/Literat/mtn109.htm. [1] (9 pages)

- Handbook Of Microwave Component Measurements. Wiley. 2012.

|