Place:Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

Macedonia Μακεδονία | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Macedonia in 336 BC (orange) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Macedonian, Attic, Koine Greek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Greek polytheism, Hellenistic religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Macedonian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hereditary monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basileus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 359–336 BC | Philip II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 336–323 BC | Alexander the Great | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 179–168 BC | Perseus (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 149–148 BC | Andriscus (rebel claim) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Synedrion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• legendary foundation by Caranus or Perdiccas I | 7th century BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Vassal of Persia[3] | 512/511–493 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Incorporated into the Persian Empire[3] | 492–479 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Rise of Macedon | 359–336 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Founding of the Hellenic League | 338–337 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Conquest of Persia | 335–323 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Partition of Babylon | 323 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Wars of the Diadochi | 322–275 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Battle of Pydna | 168 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 323 BC[4][5] | 5,200,000 km2 (2,000,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

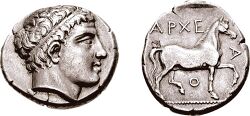

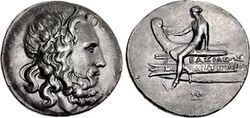

| Currency | Tetradrachm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Macedonia (/ˌmæsɪˈdoʊniə/ (![]() listen) MASS-ih-DOH-nee-ə; Greek: Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (/ˈmæsɪdɒn/ MASS-ih-don), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece,[6] which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece.[7] The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal Argead dynasty, which was followed by the Antipatrid and Antigonid dynasties. Home to the ancient Macedonians, the earliest kingdom was centered on the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula,[8] and bordered by Epirus to the southwest, Illyria to the northwest, Paeonia to the north, Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south.

listen) MASS-ih-DOH-nee-ə; Greek: Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (/ˈmæsɪdɒn/ MASS-ih-don), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece,[6] which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece.[7] The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal Argead dynasty, which was followed by the Antipatrid and Antigonid dynasties. Home to the ancient Macedonians, the earliest kingdom was centered on the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula,[8] and bordered by Epirus to the southwest, Illyria to the northwest, Paeonia to the north, Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south.

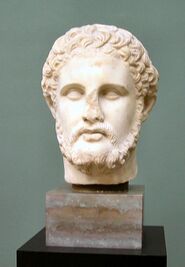

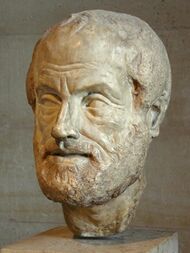

Before the 4th century BC, Macedonia was a small kingdom outside of the area dominated by the great city-states of Athens, Sparta and Thebes, and briefly subordinate to Achaemenid Persia.[3] During the reign of the Argead king Philip II (359–336 BC), Macedonia subdued mainland Greece and the Thracian Odrysian kingdom through conquest and diplomacy. With a reformed army containing phalanxes wielding the sarissa pike, Philip II defeated the old powers of Athens and Thebes in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. Philip II's son Alexander the Great, leading a federation of Greek states, accomplished his father's objective of commanding the whole of Greece when he destroyed Thebes after the city revolted. During Alexander's subsequent campaign of conquest, he overthrew the Achaemenid Empire and conquered territory that stretched as far as the Indus River. For a brief period, his Macedonian Empire was the most powerful in the world – the definitive Hellenistic state, inaugurating the transition to a new period of Ancient Greek civilization. Greek arts and literature flourished in the new conquered lands and advances in philosophy, engineering, and science spread across the empire and beyond. Of particular importance were the contributions of Aristotle, tutor to Alexander, whose writings became a keystone of Western philosophy.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the ensuing wars of the Diadochi, and the partitioning of Alexander's short-lived empire, Macedonia remained a Greek cultural and political center in the Mediterranean region along with Ptolemaic Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, and the Attalid kingdom. Important cities such as Pella, Pydna, and Amphipolis were involved in power struggles for control of the territory. New cities were founded, such as Thessalonica by the usurper Cassander (named after his wife Thessalonike of Macedon).[9] Macedonia's decline began with the Macedonian Wars and the rise of Rome as the leading Mediterranean power. At the end of the Third Macedonian War in 168 BC, the Macedonian monarchy was abolished and replaced by Roman client states. A short-lived revival of the monarchy during the Fourth Macedonian War in 150–148 BC ended with the establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia.

The Macedonian kings, who wielded absolute power and commanded state resources such as gold and silver, facilitated mining operations to mint currency, finance their armies and, by the reign of Philip II, a Macedonian navy. Unlike the other diadochi successor states, the imperial cult fostered by Alexander was never adopted in Macedonia, yet Macedonian rulers nevertheless assumed roles as high priests of the kingdom and leading patrons of domestic and international cults of the Hellenistic religion. The authority of Macedonian kings was theoretically limited by the institution of the army, while a few municipalities within the Macedonian commonwealth enjoyed a high degree of autonomy and even had democratic governments with popular assemblies.

Etymology

The name Macedonia (Greek: Μακεδονία, Makedonía) comes from the ethnonym Μακεδόνες (Makedónes), which itself is derived from the ancient Greek adjective μακεδνός (makednós), meaning "tall, slim", also the name of a people related to the Dorians (Herodotus), and possibly descriptive of Ancient Macedonians.[10] It is most likely cognate with the adjective μακρός (makros), meaning "long" or "tall" in Ancient Greek.[10] The name is believed to have originally meant either "highlanders", "the tall ones", or "high grown men".[note 1] Linguist Robert S. P. Beekes claims that both terms are of Pre-Greek substrate origin and cannot be explained in terms of Indo-European morphology,[11] however Filip De Decker rejects Beekesʼ arguments as insufficient.[12]

History

Early history and legend

The Classical Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides reported the legend that the Macedonian kings of the Argead dynasty were descendants of Temenus, king of Argos, and could therefore claim the mythical Heracles as one of their ancestors as well as a direct lineage from Zeus, chief god of the Greek pantheon.[13] Contradictory legends state that either Perdiccas I of Macedon or Caranus of Macedon were the founders of the Argead dynasty, with either five or eight kings before Amyntas I.[14] The assertion that the Argeads descended from Temenus was accepted by the Hellanodikai authorities of the Ancient Olympic Games, permitting Alexander I of Macedon (r. 498–454 BC) to enter the competitions owing to his perceived Greek heritage.[15] Little is known about the kingdom before the reign of Alexander I's father Amyntas I of Macedon (r. 547–498 BC) during the Archaic period.[16]

The kingdom of Macedonia was situated along the Haliacmon and Axius rivers in Lower Macedonia, north of Mount Olympus. Historian Robert Malcolm Errington suggests that one of the earliest Argead kings established Aigai (modern Vergina) as their capital in the mid-7th century BC.[17] Before the 4th century BC, the kingdom covered a region corresponding roughly to the western and central parts of the region of Macedonia in modern Greece.[18] It gradually expanded into the region of Upper Macedonia, inhabited by the Greek Lyncestae and Elimiotae tribes, and into regions of Emathia, Eordaia, Bottiaea, Mygdonia, Crestonia, and Almopia, which were inhabited by various peoples such as Thracians and Phrygians.[note 2] Macedonia's non-Greek neighbors included Thracians, inhabiting territories to the northeast, Illyrians to the northwest, and Paeonians to the north, while the lands of Thessaly to the south and Epirus to the west were inhabited by Greeks with similar cultures to that of the Macedonians.[19]

A year after Darius I of Persia (r. 522–486 BC) launched an invasion into Europe against the Scythians, Paeonians, Thracians, and several Greek city-states of the Balkans, the Persian general Megabazus used diplomacy to convince Amyntas I to submit as a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire, ushering in the period of Achaemenid Macedonia.[note 3] Achaemenid Persian hegemony over Macedonia was briefly interrupted by the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BC), yet the Persian general Mardonius brought it back under Achaemenid suzerainty.[22]

Although Macedonia enjoyed a large degree of autonomy and was never made a satrapy (i.e. province) of the Achaemenid Empire, it was expected to provide troops for the Achaemenid army.[23] Alexander I provided Macedonian military support to Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC) during the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480–479 BC, and Macedonian soldiers fought on the side of the Persians at the 479 BC Battle of Platea.[24] Following the Greek victory at Salamis in 480 BC, Alexander I was employed as an Achaemenid diplomat to propose a peace treaty and alliance with Athens, an offer that was rejected.[25] Soon afterwards, the Achaemenid forces were forced to withdraw from mainland Europe, marking the end of Persian control over Macedonia.[26]

Involvement in the Classical Greek world

Although initially a Persian vassal, Alexander I of Macedon fostered friendly diplomatic relations with his former Greek enemies, the Athenian and Spartan-led coalition of Greek city-states.[27] His successor Perdiccas II (r. 454–413 BC) led the Macedonians to war in four separate conflicts against Athens, leader of the Delian League, while incursions by the Thracian ruler Sitalces of the Odrysian kingdom threatened Macedonia's territorial integrity in the northeast.[28] The Athenian statesman Pericles promoted colonization of the Strymon River near the Kingdom of Macedonia, where the colonial city of Amphipolis was founded in 437/436 BC so that it could provide Athens with a steady supply of silver and gold as well as timber and pitch to support the Athenian navy.[29] Initially Perdiccas II did not take any action and might have even welcomed the Athenians, as the Thracians were foes to both of them.[30] This changed due to an Athenian alliance with a brother and cousin of Perdiccas II who had rebelled against him.[30] Thus, two separate wars were fought against Athens between 433 and 431 BC.[30] The Macedonian king retaliated by promoting the rebellion of Athens' allies in Chalcidice and subsequently won over the strategic city of Potidaea.[31] After capturing the Macedonian cities Therma and Beroea, Athens besieged Potidaea but failed to overcome it; Therma was returned to Macedonia and much of Chalcidice to Athens in a peace treaty brokered by Sitalces, who provided Athens with military aid in exchange for acquiring new Thracian allies.[32]

Perdiccas II sided with Sparta in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between Athens and Sparta, and in 429 BC Athens retaliated by persuading Sitalces to invade Macedonia, but he was forced to retreat owing to a shortage of provisions in winter.[33] In 424 BC, Arrhabaeus, a local ruler of Lynkestis in Upper Macedonia, rebelled against his overlord Perdiccas, and the Spartans agreed to help in putting down the revolt.[34] At the Battle of Lyncestis the Macedonians panicked and fled before the fighting began, enraging the Spartan general Brasidas, whose soldiers looted the unattended Macedonian baggage train.[35] Perdiccas then changed sides and supported Athens, and he was able to put down Arrhabaeus's revolt.[36]

Brasidas died in 422 BC, the year Athens and Sparta struck an accord, the Peace of Nicias, that freed Macedonia from its obligations as an Athenian ally.[37] Following the 418 BC Battle of Mantinea, the victorious Spartans formed an alliance with Argos, a military pact Perdiccas II was keen to join given the threat of Spartan allies remaining in Chalcidice.[38] When Argos suddenly switched sides as a pro-Athenian democracy, the Athenian navy was able to form a blockade against Macedonian seaports and invade Chalcidice in 417 BC.[39] Perdiccas II sued for peace in 414 BC, forming an alliance with Athens that was continued by his son and successor Archelaus I (r. 413–399 BC).[40] Athens then provided naval support to Archelaus I in the 410 BC Macedonian siege of Pydna, in exchange for timber and naval equipment.[41]

Although Archelaus I was faced with some internal revolts and had to fend off an invasion of Illyrians led by Sirras of Lynkestis, he was able to project Macedonian power into Thessaly where he sent military aid to his allies.[42] Although he retained Aigai as a ceremonial and religious center, Archelaus I moved the capital of the kingdom north to Pella, which was then positioned by a lake with a river connecting it to the Aegean Sea.[43] He improved Macedonia's currency by minting coins with a higher silver content as well as issuing separate copper coinage.[44] His royal court attracted the presence of well-known intellectuals such as the Athenian playwright Euripides.[45] When Archelaus I was assassinated (perhaps following a homosexual love affair with royal pages at his court), the kingdom was plunged into chaos, in an era lasting from 399 to 393 BC that included the reign of four different monarchs: Orestes, son of Archelaus I; Aeropus II, uncle, regent, and murderer of Orestes; Pausanias, son of Aeropus II; and Amyntas II, who was married to the youngest daughter of Archelaus I.[46] Very little is known about this turbulent period; it came to an end when Amyntas III (r. 393–370 BC), son of Arrhidaeus and grandson of Amyntas I, killed Pausanias and claimed the Macedonian throne.[47]

Amyntas III was forced to flee his kingdom in either 393 or 383 BC (based on conflicting accounts), owing to a massive invasion by the Illyrians led by Bardylis.[note 4] The pretender to the throne Argaeus ruled in his absence, yet Amyntas III eventually returned to his kingdom with the aid of Thessalian allies.[48] Amyntas III was also nearly overthrown by the forces of the Chalcidian city of Olynthos, but with the aid of Teleutias, brother of the Spartan king Agesilaus II, the Macedonians forced Olynthos to surrender and dissolve their Chalcidian League in 379 BC.[49]

Alexander II (r. 370–368 BC), son of Eurydice I and Amyntas III, succeeded his father and immediately invaded Thessaly to wage war against the tagus (supreme Thessalian military leader) Alexander of Pherae, capturing the city of Larissa.[50] The Thessalians, desiring to remove both Alexander II and Alexander of Pherae as their overlords, appealed to Pelopidas of Thebes for aid; he succeeded in recapturing Larissa and, in the peace agreement arranged with Macedonia, received aristocratic hostages including Alexander II's brother and future king Philip II (r. 359–336 BC).[51] When Alexander was assassinated by his brother-in-law Ptolemy of Aloros, the latter acted as an overbearing regent for Perdiccas III (r. 368–359 BC), younger brother of Alexander II, who eventually had Ptolemy executed when reaching the age of majority in 365 BC.[52] The remainder of Perdiccas III's reign was marked by political stability and financial recovery.[53] However, an Athenian invasion led by Timotheus, son of Conon, managed to capture Methone and Pydna, and an Illyrian invasion led by Bardylis succeeded in killing Perdiccas III and 4,000 Macedonian troops in battle.[54]

Rise of Macedon

Philip II was twenty-four years old when he acceded to the throne in 359 BC.[55] Through the use of deft diplomacy, he was able to convince the Thracians under Berisades to cease their support of Pausanias, a pretender to the throne, and the Athenians to halt their support of another pretender.[56] He achieved these by bribing the Thracians and their Paeonian allies and establishing a treaty with Athens that relinquished his claims to Amphipolis.[57] He was also able to make peace with the Illyrians who had threatened his borders.[58]

Philip II spent his initial years radically transforming the Macedonian army. A reform of its organization, equipment, and training, including the introduction of the Macedonian phalanx armed with long pikes (i.e. the sarissa), proved immediately successful when tested against his Illyrian and Paeonian enemies.[59] Confusing accounts in ancient sources have led modern scholars to debate how much Philip II's royal predecessors may have contributed to these reforms and the extent to which his ideas were influenced by his adolescent years of captivity in Thebes as a political hostage during the Theban hegemony, especially after meeting with the general Epaminondas.[60]

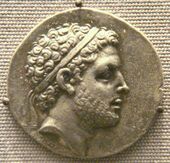

The Macedonians, like the other Greeks, traditionally practiced monogamy, but Philip II practiced polygamy and married seven wives with perhaps only one that did not involve the loyalty of his aristocratic subjects or new allies.[note 5] His first marriages were to Phila of Elimeia of the Upper Macedonian aristocracy as well as the Illyrian princess Audata to ensure a marriage alliance.[61] To establish an alliance with Larissa in Thessaly, he married the Thessalian noblewoman Philinna in 358 BC, who bore him a son who would later rule as Philip III Arrhidaeus (r. 323–317 BC).[62] In 357 BC, he married Olympias to secure an alliance with Arybbas, the King of Epirus and the Molossians. This marriage would bear a son who would later rule as Alexander III (better known as Alexander the Great) and claim descent from the legendary Achilles by way of his dynastic heritage from Epirus.[63] It is unclear whether or not the Achaemenid Persian kings influenced Philip II's practice of polygamy, although his predecessor Amyntas III had three sons with a possible second wife Gygaea: Archelaus, Arrhidaeus, and Menelaus.[64] Philip II had Archelaus put to death in 359 BC, while Philip II's other two half brothers fled to Olynthos, serving as a casus belli for the Olynthian War (349–348 BC) against the Chalcidian League.[65]

While Athens was preoccupied with the Social War (357–355 BC), Philip II retook Amphipolis from them in 357 BC and the following year recaptured Pydna and Potidaea, the latter of which he handed over to the Chalcidian League as promised in a treaty.[66] In 356 BC, he took Crenides, refounding it as Philippi, while his general Parmenion defeated the Illyrian king Grabos II of the Grabaei.[67] During the 355–354 BC siege of Methone, Philip II lost his right eye to an arrow wound, but managed to capture the city and treated the inhabitants cordially, unlike the Potidaeans, who had been enslaved.[note 6]

Philip II then involved Macedonia in the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC). It began when Phocis captured and plundered the temple of Apollo at Delphi instead of submitting unpaid fines, causing the Amphictyonic League to declare war on Phocis and a civil war among the members of the Thessalian League aligned with either Phocis or Thebes.[68] Philip II's initial campaign against Pherae in Thessaly in 353 BC at the behest of Larissa ended in two disastrous defeats by the Phocian general Onomarchus.[note 7] Philip II in turn defeated Onomarchus in 352 BC at the Battle of Crocus Field, which led to Philip II's election as leader (archon) of the Thessalian League, provided him a seat on the Amphictyonic Council, and allowed for a marriage alliance with Pherae by wedding Nicesipolis, niece of the tyrant Jason of Pherae.[69]

Philip II had some early involvement with the Achaemenid Empire, especially by supporting satraps and mercenaries who rebelled against the central authority of the Achaemenid king. The satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia Artabazos II, who was in rebellion against Artaxerxes III, was able to take refuge as an exile at the Macedonian court from 352 to 342 BC. He was accompanied in exile by his family and by his mercenary general Memnon of Rhodes.[70][71] Barsine, daughter of Artabazos, and future wife of Alexander the Great, grew up at the Macedonian court.[71]

After campaigning against the Thracian ruler Cersobleptes, in 349 BC, Philip II began his war against the Chalcidian League, which had been reestablished in 375 BC following a temporary disbandment.[72] Despite an Athenian intervention by Charidemus,[73] Olynthos was captured by Philip II in 348 BC, and its inhabitants were sold into slavery, including some Athenian citizens.[74] The Athenians, especially in a series of speeches by Demosthenes known as the Olynthiacs, were unsuccessful in persuading their allies to counterattack and in 346 BC concluded a treaty with Macedonia known as the Peace of Philocrates.[75] The treaty stipulated that Athens would relinquish claims to Macedonian coastal territories, the Chalcidice, and Amphipolis in return for the release of the enslaved Athenians as well as guarantees that Philip II would not attack Athenian settlements in the Thracian Chersonese.[76] Meanwhile, Phocis and Thermopylae were captured by Macedonian forces, the Delphic temple robbers were executed, and Philip II was awarded the two Phocian seats on the Amphictyonic Council and the position of master of ceremonies over the Pythian Games.[77] Athens initially opposed his membership on the council and refused to attend the games in protest, but they eventually accepted these conditions, perhaps after some persuasion by Demosthenes in his oration On the Peace.[78]

Over the next few years, Philip II reformed local governments in Thessaly, campaigned against the Illyrian ruler Pleuratus I, deposed Arybbas in Epirus in favor of his brother-in-law Alexander I (through Philip II's marriage to Olympias), and defeated Cersebleptes in Thrace. This allowed him to extend Macedonian control over the Hellespont in anticipation of an invasion into Achaemenid Anatolia.[80] In 342 BC, Philip II conquered a Thracian city in what is now Bulgaria and renamed it Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv).[81] War broke out with Athens in 340 BC while Philip II was engaged in two ultimately unsuccessful sieges of Perinthus and Byzantion, followed by a successful campaign against the Scythians along the Danube and Macedonia's involvement in the Fourth Sacred War against Amphissa in 339 BC.[82] Thebes ejected a Macedonian garrison from Nicaea (near Thermopylae), leading Thebes to join Athens, Megara, Corinth, Achaea, and Euboea in a final confrontation against Macedonia at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC.[83] After the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea, Philip II installed an oligarchy in Thebes, yet was lenient toward Athens, wishing to utilize their navy in a planned invasion of the Achaemenid Empire.[84] He was then chiefly responsible for the formation of the League of Corinth that included the major Greek city-states except Sparta. Despite the Kingdom of Macedonia's official exclusion from the league, in 337 BC, Philip II was elected as the leader (hegemon) of its council (synedrion) and the commander-in-chief (strategos autokrator) of a forthcoming campaign to invade the Achaemenid Empire.[85] Philip's plan to punish the Persians for the suffering of the Greeks and to liberate the Greek cities of Asia Minor[86] as well as perhaps the panhellenic fear of another Persian invasion of Greece, contributed to his decision to invade the Achaemenid Empire.[87] The Persians offered aid to Perinthus and Byzantion in 341–340 BC, highlighting Macedonia's strategic need to secure Thrace and the Aegean Sea against increasing Achaemenid encroachment, as the Persian king Artaxerxes III further consolidated his control over satrapies in western Anatolia.[88] The latter region, yielding far more wealth and valuable resources than the Balkans, was also coveted by the Macedonian king for its sheer economic potential.[89]

When Philip II married Cleopatra Eurydice, niece of general Attalus, talk of providing new potential heirs at the wedding feast infuriated Philip II's son Alexander, a veteran of the Battle of Chaeronea, and his mother Olympias.[90] They fled together to Epirus before Alexander was recalled to Pella by Philip II.[90] When Philip II arranged a marriage between his son Arrhidaeus and Ada of Caria, daughter of Pixodarus, the Persian satrap of Caria, Alexander intervened and proposed to marry Ada instead. Philip II then cancelled the wedding altogether and exiled Alexander's advisors Ptolemy, Nearchus, and Harpalus.[91] To reconcile with Olympias, Philip II had their daughter Cleopatra marry Olympias' brother (and Cleopatra's uncle) Alexander I of Epirus, but Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard, Pausanias of Orestis, during their wedding feast and succeeded by Alexander in 336 BC.[92]

Empire

Modern scholars have argued over the possible role of Alexander III "the Great" and his mother Olympias in the assassination of Philip II, noting the latter's choice to exclude Alexander from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as regent of Greece and deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth, and the potential bearing of another male heir between Philip II and his new wife, Cleopatra Eurydice.[note 8] Alexander III (r. 336–323 BC) was immediately proclaimed king by an assembly of the army and leading aristocrats, chief among them being Antipater and Parmenion.[93] By the end of his reign and military career in 323 BC, Alexander would rule over an empire consisting of mainland Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and much of Central and South Asia (i.e. modern Pakistan ).[94] Among his first acts was the burial of his father at Aigai.[95] The members of the League of Corinth revolted at the news of Philip II's death, but were soon quelled by military force alongside persuasive diplomacy, electing Alexander as hegemon of the league to carry out the planned invasion of Achaemenid Persia.[96]

In 335 BC, Alexander fought against the Thracian tribe of the Triballi at Haemus Mons and along the Danube, forcing their surrender on Peuce Island.[97] Shortly thereafter, the Illyrian chieftain Cleitus, son of Bardylis, threatened to attack Macedonia with the aid of Glaucias, king of the Taulantii, but Alexander took the initiative and besieged the Illyrians at Pelion (in modern Albania).[98] When Thebes had once again revolted from the League of Corinth and was besieging the Macedonian garrison in the Cadmea, Alexander left the Illyrian front and marched to Thebes, which he placed under siege.[99] After breaching the walls, Alexander's forces killed 6,000 Thebans, took 30,000 inhabitants as prisoners of war, and burned the city to the ground as a warning that convinced all other Greek states except Sparta not to challenge Alexander again.[100]

Throughout his military career, Alexander won every battle that he personally commanded.[101] His first victory against the Persians in Asia Minor at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC used a small cavalry contingent as a distraction to allow his infantry to cross the river followed by a cavalry charge from his companion cavalry.[102] Alexander led the cavalry charge at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, forcing the Persian king Darius III and his army to flee.[102] Darius III, despite having superior numbers, was again forced to flee the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC.[102] The Persian king was later captured and executed by his own satrap of Bactria and kinsman, Bessus, in 330 BC. The Macedonian king subsequently hunted down and executed Bessus in what is now Afghanistan, securing the region of Sogdia in the process.[103] At the 326 BC Battle of the Hydaspes (modern-day Punjab), when the war elephants of King Porus of the Pauravas threatened Alexander's troops, he had them form open ranks to surround the elephants and dislodge their handlers by using their sarissa pikes.[104] When his Macedonian troops threatened mutiny in 324 BC at Opis, Babylonia (near modern Baghdad, Iraq), Alexander offered Macedonian military titles and greater responsibilities to Persian officers and units instead, forcing his troops to seek forgiveness at a staged banquet of reconciliation between Persians and Macedonians.[105]

Alexander perhaps undercut his own rule by demonstrating signs of megalomania.[106] While utilizing effective propaganda such as the cutting of the Gordian Knot, he also attempted to portray himself as a living god and son of Zeus following his visit to the oracle at Siwah in the Libyan Desert (in modern-day Egypt) in 331 BC.[107] His attempt in 327 BC to have his men prostrate before him in Bactra in an act of proskynesis borrowed from the Persian kings was rejected as religious blasphemy by his Macedonian and Greek subjects after his court historian Callisthenes refused to perform this ritual.[106] When Alexander had Parmenion murdered at Ecbatana (near modern Hamadan, Iran) in 330 BC, this was "symptomatic of the growing gulf between the king's interests and those of his country and people", according to Errington.[108] His murder of Cleitus the Black in 328 BC is described as "vengeful and reckless" by Dawn L. Gilley and Ian Worthington.[109] Continuing the polygamous habits of his father, Alexander encouraged his men to marry native women in Asia, leading by example when he wed Roxana, a Sogdian princess of Bactria.[110] He then married Stateira II, eldest daughter of Darius III, and Parysatis II, youngest daughter of Artaxerxes III, at the Susa weddings in 324 BC.[111]

Meanwhile, in Greece, the Spartan king Agis III attempted to lead a rebellion of the Greeks against Macedonia.[112] He was defeated in 331 BC at the Battle of Megalopolis by Antipater, who was serving as regent of Macedonia and deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth in Alexander's stead.[note 9] Before Antipater embarked on his campaign in the Peloponnese, Memnon, the governor of Thrace, was dissuaded from rebellion by use of diplomacy.[113] Antipater deferred the punishment of Sparta to the League of Corinth headed by Alexander, who ultimately pardoned the Spartans on the condition that they submit fifty nobles as hostages.[114] Antipater's hegemony was somewhat unpopular in Greece due to his practice (perhaps by order of Alexander) of exiling malcontents and garrisoning cities with Macedonian troops, yet in 330 BC, Alexander declared that the tyrannies installed in Greece were to be abolished and Greek freedom was to be restored.[115]

When Alexander the Great died at Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias immediately accused Antipater and his faction of poisoning him, although there is no evidence to confirm this.[116] With no official heir apparent, the Macedonian military command split, with one side proclaiming Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (r. 323–317 BC) as king and the other siding with the infant son of Alexander and Roxana, Alexander IV (r. 323–309 BC).[117] Except for the Euboeans and Boeotians, the Greeks also immediately rose up in a rebellion against Antipater known as the Lamian War (323–322 BC).[118] When Antipater was defeated at the 323 BC Battle of Thermopylae, he fled to Lamia where he was besieged by the Athenian commander Leosthenes. A Macedonian army led by Leonnatus rescued Antipater by lifting the siege.[119] Antipater defeated the rebellion, yet his death in 319 BC left a power vacuum wherein the two proclaimed kings of Macedonia became pawns in a power struggle between the diadochi, the former generals of Alexander's army.[120]

A council of the army convened in Babylon immediately after Alexander's death, naming Philip III as king and the chiliarch Perdiccas as his regent.[121] Antipater, Antigonus Monophthalmus, Craterus, and Ptolemy formed a coalition against Perdiccas in a civil war initiated by Ptolemy's seizure of the hearse of Alexander the Great.[122] Perdiccas was assassinated in 321 BC by his own officers during a failed campaign in Egypt against Ptolemy, where his march along the Nile River resulted in the drowning of 2,000 of his men.[123] Although Eumenes of Cardia managed to kill Craterus in battle, this had little to no effect on the outcome of the 321 BC Partition of Triparadisus in Syria where the victorious coalition settled the issue of a new regency and territorial rights.[124] Antipater was appointed as regent over the two kings. Before Antipater died in 319 BC, he named the staunch Argead loyalist Polyperchon as his successor, passing over his own son Cassander and ignoring the right of the king to choose a new regent (since Philip III was considered mentally unstable), in effect bypassing the council of the army as well.[125]

Forming an alliance with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus, Cassander had his officer Nicanor capture the Munichia fortress of Athens' port town Piraeus in defiance of Polyperchon's decree that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian garrisons, sparking the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).[126] Given a string of military failures by Polyperchon, in 317 BC, Philip III, by way of his politically engaged wife Eurydice II of Macedon, officially replaced him as regent with Cassander.[127] Afterwards, Polyperchon desperately sought the aid of Olympias in Epirus.[127] A joint force of Epirotes, Aetolians, and Polyperchon's troops invaded Macedonia and forced the surrender of Philip III and Eurydice's army, allowing Olympias to execute the king and force his queen to commit suicide.[128] Olympias then had Nicanor and dozens of other Macedonian nobles killed, but by the spring of 316 BC, Cassander had defeated her forces, captured her, and placed her on trial for murder before sentencing her to death.[129]

Cassander married Philip II's daughter Thessalonike and briefly extended Macedonian control into Illyria as far as Epidamnos (modern Durrës, Albania). By 313 BC, it was retaken by the Illyrian king Glaucias of Taulantii.[130] By 316 BC, Antigonus had taken the territory of Eumenes and managed to eject Seleucus Nicator from his Babylonian satrapy, leading Cassander, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus to issue a joint ultimatum to Antigonus in 315 BC for him to surrender various territories in Asia.[9] Antigonus promptly allied with Polyperchon, now based in Corinth, and issued an ultimatum of his own to Cassander, charging him with murder for executing Olympias and demanding that he hand over the royal family, King Alexander IV and the queen mother Roxana.[131] The conflict that followed lasted until the winter of 312/311 BC, when a new peace settlement recognized Cassander as general of Europe, Antigonus as "first in Asia", Ptolemy as general of Egypt, and Lysimachus as general of Thrace.[132] Cassander had Alexander IV and Roxana put to death in the winter of 311/310 BC, and between 306 and 305 BC the diadochi were declared kings of their respective territories.[133]

Hellenistic era

The beginning of Hellenistic Greece was defined by the struggle between the Antipatrid dynasty, led first by Cassander (r. 305–297 BC), son of Antipater, and the Antigonid dynasty, led by the Macedonian general Antigonus I Monophthalmus (r. 306–301 BC) and his son, the future king Demetrius I (r. 294–288 BC). Cassander besieged Athens in 303 BC, but was forced to retreat to Macedonia when Demetrius invaded Boeotia to his rear, attempting to sever his path of retreat.[134] While Antigonus and Demetrius attempted to recreate Philip II's Hellenic league with themselves as dual hegemons, a revived coalition of Cassander, Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305–283 BC) of Egypt's Ptolemaic dynasty, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305–281 BC) of the Seleucid Empire, and Lysimachus (r. 306–281 BC), King of Thrace, defeated the Antigonids at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, killing Antigonus and forcing Demetrius into flight.[135]

Cassander died in 297 BC, and his sickly son Philip IV died the same year, succeeded by Cassander's other sons Alexander V of Macedon (r. 297–294 BC) and Antipater II of Macedon (r. 297–294 BC), with their mother Thessalonike of Macedon acting as regent.[136] While Demetrius fought against the Antipatrid forces in Greece, Antipater II killed his own mother to obtain power.[136] His desperate brother Alexander V then requested aid from Pyrrhus of Epirus (r. 297–272 BC),[136] who had fought alongside Demetrius at the Battle of Ipsus, but was sent to Egypt as a hostage as part of an agreement between Demetrius and Ptolemy I.[137] In exchange for defeating the forces of Antipater II and forcing him to flee to the court of Lysimachus in Thrace, Pyrrhus was awarded the westernmost portions of the Macedonian kingdom.[138] Demetrius had his nephew Alexander V assassinated and was then proclaimed king of Macedonia, but his subjects protested against his aloof, Eastern-style autocracy.[136]

War broke out between Pyrrhus and Demetrius in 290 BC when Lanassa, wife of Pyrrhus, daughter of Agathocles of Syracuse, left him for Demetrius and offered him her dowry of Corcyra.[139] The war dragged on until 288 BC, when Demetrius lost the support of the Macedonians and fled the country. Macedonia was then divided between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus, the former taking western Macedonia and the latter eastern Macedonia.[139] By 286 BC, Lysimachus had expelled Pyrrhus and his forces from Macedonia.[note 10] In 282 BC, a new war erupted between Seleucus I and Lysimachus; the latter was killed in the Battle of Corupedion, allowing Seleucus I to take control of Thrace and Macedonia.[140] In two dramatic reversals of fortune, Seleucus I was assassinated in 281 BC by his officer Ptolemy Keraunos, son of Ptolemy I and grandson of Antipater, who was then proclaimed king of Macedonia before being killed in battle in 279 BC by Celtic invaders in the Gallic invasion of Greece.[141] The Macedonian army proclaimed the general Sosthenes of Macedon as king, although he apparently refused the title.[142] After defeating the Gallic ruler Bolgios and driving out the raiding party of Brennus, Sosthenes died and left a chaotic situation in Macedonia.[143] The Gallic invaders ravaged Macedonia until Antigonus Gonatas, son of Demetrius, defeated them in Thrace at the 277 BC Battle of Lysimachia and was then proclaimed king Antigonus II of Macedon (r. 277–274, 272–239 BC).[144]

In 280 BC, Pyrrhus embarked on a campaign in Magna Graecia (i.e. southern Italy) against the Roman Republic known as the Pyrrhic War, followed by his invasion of Sicily.[145] Ptolemy Keraunos secured his position on the Macedonian throne by giving Pyrrhus five thousand soldiers and twenty war elephants for this endeavor.[137] Pyrrhus returned to Epirus in 275 BC after the ultimate failure of both campaigns, which contributed to the rise of Rome because Greek cities in southern Italy such as Tarentum now became Roman allies.[145] Pyrrhus invaded Macedonia in 274 BC, defeating the largely mercenary army of Antigonus II at the 274 BC Battle of Aous and driving him out of Macedonia, forcing him to seek refuge with his naval fleet in the Aegean.[146]

Pyrrhus lost much of his support among the Macedonians in 273 BC when his unruly Gallic mercenaries plundered the royal cemetery of Aigai.[147] Pyrrhus pursued Antigonus II in the Peloponnese, yet Antigonus II was ultimately able to recapture Macedonia.[148] Pyrrhus was killed while besieging Argos in 272 BC, allowing Antigonus II to reclaim the rest of Greece.[149] He then restored the Argead dynastic graves at Aigai and annexed the Kingdom of Paeonia.[150]

The Aetolian League hampered Antigonus II's control over central Greece, and the formation of the Achaean League in 251 BC pushed Macedonian forces out of much of the Peloponnese and at times incorporated Athens and Sparta.[151] While the Seleucid Empire aligned with Antigonid Macedonia against Ptolemaic Egypt during the Syrian Wars, the Ptolemaic navy heavily disrupted Antigonus II's efforts to control mainland Greece.[152] With the aid of the Ptolemaic navy, the Athenian statesman Chremonides led a revolt against Macedonian authority known as the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC).[153] By 265 BC, Athens was surrounded and besieged by Antigonus II's forces, and a Ptolemaic fleet was defeated in the Battle of Cos. Athens finally surrendered in 261 BC.[154] After Macedonia formed an alliance with the Seleucid ruler Antiochus II, a peace settlement between Antigonus II and Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt was finally struck in 255 BC.[155]

In 251 BC, Aratus of Sicyon led a rebellion against Antigonus II, and in 250 BC, Ptolemy II declared his support for the self-proclaimed King Alexander of Corinth.[157] Although Alexander died in 246 BC and Antigonus was able to score a naval victory against the Ptolemies at Andros, the Macedonians lost the Acrocorinth to the forces of Aratus in 243 BC, followed by the induction of Corinth into the Achaean League.[158] Antigonus II made peace with the Achaean League in 240 BC, ceding the territories that he had lost in Greece.[159] Antigonus II died in 239 BC and was succeeded by his son Demetrius II of Macedon (r. 239–229 BC). Seeking an alliance with Macedonia to defend against the Aetolians, the queen mother and regent of Epirus, Olympias II, offered her daughter Phthia of Macedon to Demetrius II in marriage. Demetrius II accepted her proposal, but he damaged relations with the Seleucids by divorcing Stratonice of Macedon.[160] Although the Aetolians formed an alliance with the Achaean League as a result, Demetrius II was able to invade Boeotia and capture it from the Aetolians by 236 BC.[156]

The Achaean League managed to capture Megalopolis in 235 BC, and by the end of Demetrius II's reign most of the Peloponnese except Argos was taken from the Macedonians.[161] Demetrius II also lost an ally in Epirus when the monarchy was toppled in a republican revolution.[162] Demetrius II enlisted the aid of the Illyrian king Agron to defend Acarnania against Aetolia, and in 229 BC, they managed to defeat the combined navies of the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues at the Battle of Paxos.[162] Another Illyrian ruler, Longarus of the Dardanian Kingdom, invaded Macedonia and defeated an army of Demetrius II shortly before his death in 229 BC.[163] Although his young son Philip immediately inherited the throne, his regent Antigonus III Doson (r. 229–221 BC), nephew of Antigonus II, was proclaimed king by the army, with Philip as his heir, following a string of military victories against the Illyrians in the north and the Aetolians in Thessaly.[164]

Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC seeking an unexpected alliance now that the reformist king Cleomenes III of Sparta was threatening the rest of Greece in the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC).[165] In exchange for military aid, Antigonus III demanded the return of Corinth to Macedonian control, which Aratus finally agreed to in 225 BC.[166] In 224 BC, Antigonus III's forces took Arcadia from Sparta. After forming a Hellenic league in the same vein as Philip II's League of Corinth, he managed to defeat Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC.[167] Sparta was occupied by a foreign power for the first time in its history, restoring Macedonia's position as the leading power in Greece.[168] Antigonus died a year later, perhaps from tuberculosis, leaving behind a strong Hellenistic kingdom for his successor Philip V.[169]

Philip V of Macedon (r. 221–179 BC) faced immediate challenges to his authority by the Illyrian Dardani and Aetolian League.[170] Philip V and his allies were successful against the Aetolians and their allies in the Social War (220–217 BC), yet he made peace with the Aetolians once he heard of incursions by the Dardani in the north and the Carthaginian victory over the Romans at the Battle of Lake Trasimene in 217 BC.[171] Demetrius of Pharos is alleged to have convinced Philip V to first secure Illyria in advance of an invasion of the Italian peninsula.[note 11] In 216 BC, Philip V sent a hundred light warships into the Adriatic Sea to attack Illyria, a move that prompted Scerdilaidas of the Ardiaean Kingdom to appeal to the Romans for aid.[172] Rome responded by sending ten heavy quinqueremes from Roman Sicily to patrol the Illyrian coasts, causing Philip V to reverse course and order his fleet to retreat, averting open conflict for the time being.[173]

Conflict with Rome

In 215 BC, at the height of the Second Punic War with the Carthaginian Empire, Roman authorities intercepted a ship off the Calabrian coast holding a Macedonian envoy and a Carthaginian ambassador in possession of a treaty composed by Hannibal declaring an alliance with Philip V.[174] The treaty stipulated that Carthage had the sole right to negotiate the terms of Rome's hypothetical surrender and promised mutual aid if a resurgent Rome should seek revenge against either Macedonia or Carthage.[175] Although the Macedonians were perhaps only interested in safeguarding their newly conquered territories in Illyria,[176] the Romans were nevertheless able to thwart whatever grand ambitions Philip V had for the Adriatic region during the First Macedonian War (214–205 BC). In 214 BC, Rome positioned a naval fleet at Oricus, which was assaulted along with Apollonia by Macedonian forces.[177] When the Macedonians captured Lissus in 212 BC, the Roman Senate responded by inciting the Aetolian League, Sparta, Elis, Messenia, and Attalus I (r. 241–197 BC) of Pergamon to wage war against Philip V, keeping him occupied and away from Italy.[178]

The Aetolian League concluded a peace agreement with Philip V in 206 BC, and the Roman Republic negotiated the Treaty of Phoenice in 205 BC, ending the war and allowing the Macedonians to retain some captured settlements in Illyria.[179] Although the Romans rejected an Aetolian request in 202 BC for Rome to declare war on Macedonia once again, the Roman Senate gave serious consideration to the similar offer made by Pergamon and its ally Rhodes in 201 BC.[180] These states were concerned about Philip V's alliance with Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire, which invaded the war-weary and financially exhausted Ptolemaic Empire in the Fifth Syrian War (202–195 BC) as Philip V captured Ptolemaic settlements in the Aegean Sea.[181] Although Rome's envoys played a critical role in convincing Athens to join the anti-Macedonian alliance with Pergamon and Rhodes in 200 BC, the comitia centuriata (people's assembly) rejected the Roman Senate's proposal for a declaration of war on Macedonia.[182] Meanwhile, Philip V conquered territories in the Hellespont and Bosporus as well as Ptolemaic Samos, which led Rhodes to form an alliance with Pergamon, Byzantium, Cyzicus, and Chios against Macedonia.[183] Despite Philip V's nominal alliance with the Seleucid king, he lost the naval Battle of Chios in 201 BC and was blockaded at Bargylia by the Rhodian and Pergamene navies.[184]

While Philip V was busy fighting Rome's Greek allies, Rome viewed this as an opportunity to punish this former ally of Hannibal with a war that they hoped would supply a victory and require few resources.[note 12] The Roman Senate demanded that Philip V cease hostilities against neighboring Greek powers and defer to an international arbitration committee for settling grievances.[185] When the comitia centuriata finally voted in approval of the Roman Senate's declaration of war in 200 BC and handed their ultimatum to Philip V, demanding that a tribunal assess the damages owed to Rhodes and Pergamon, the Macedonian king rejected it. This marked the beginning of the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC), with Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus spearheading military operations in Apollonia.[186]

The Macedonians successfully defended their territory for roughly two years,[187] but the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC, forcing his men to take refuge in Thessaly.[188] When the Achaean League switched their loyalties from Macedonia to Rome, the Macedonian king sued for peace, but the terms offered were considered too stringent, and so the war continued.[188] In June 197 BC, the Macedonians were defeated at the Battle of Cynoscephalae.[189] Rome then ratified a treaty that forced Macedonia to relinquish control of much of its Greek possessions outside of Macedonia proper, if only to act as a buffer against Illyrian and Thracian incursions into Greece.[190] Although some Greeks suspected Roman intentions of supplanting Macedonia as the new hegemonic power in Greece, Flaminius announced at the Isthmian Games of 196 BC that Rome intended to preserve Greek liberty by leaving behind no garrisons and by not exacting tribute of any kind.[191] His promise was delayed by negotiations with the Spartan king Nabis, who had meanwhile captured Argos, yet Roman forces evacuated Greece in 194 BC.[192]

Encouraged by the Aetolian League and their calls to liberate Greece from the Romans, the Seleucid king Antiochus III landed with his army at Demetrias, Thessaly, in 192 BC, and was elected strategos by the Aetolians.[193] Macedonia, the Achaean League, and other Greek city-states maintained their alliance with Rome.[194] The Romans defeated the Seleucids in the 191 BC Battle of Thermopylae as well as the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC, forcing the Seleucids to pay a war indemnity, dismantle most of its navy, and abandon its claims to any territories north or west of the Taurus Mountains in the 188 BC Treaty of Apamea.[195] With Rome's acceptance, Philip V was able to capture some cities in central Greece in 191–189 BC that had been allied to Antiochus III, while Rhodes and Eumenes II (r. 197–159 BC) of Pergamon gained territories in Asia Minor.[196]

Failing to please all sides in various territorial disputes, the Roman Senate decided in 184/183 BC to force Philip V to abandon Aenus and Maronea, since these had been declared free cities in the Treaty of Apamea.[note 13] This assuaged the fear of Eumenes II that Macedonia could pose a threat to his lands in the Hellespont.[197] Perseus of Macedon (r. 179–168 BC) succeeded Philip V and executed his brother Demetrius, who had been favored by the Romans but was charged by Perseus with high treason.[198] Perseus then attempted to form marriage alliances with Prusias II of Bithynia and Seleucus IV Philopator of the Seleucid Empire, along with renewed relations with Rhodes that greatly unsettled Eumenes II.[199] Although Eumenes II attempted to undermine these diplomatic relationships, Perseus fostered an alliance with the Boeotian League, extended his authority into Illyria and Thrace, and in 174 BC, won the role of managing the Temple of Apollo at Delphi as a member of the Amphictyonic Council.[200]

Eumenes II came to Rome in 172 BC and delivered a speech to the Senate denouncing the alleged crimes and transgressions of Perseus.[201] This convinced the Roman Senate to declare the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).[note 14] Although Perseus's forces were victorious against the Romans at the Battle of Callinicus in 171 BC, the Macedonian army was defeated at the Battle of Pydna in June 168 BC.[202] Perseus fled to Samothrace but surrendered shortly afterwards, was brought to Rome for the triumph of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, and was placed under house arrest at Alba Fucens, where he died in 166 BC.[203] The Romans abolished the Macedonian monarchy by installing four separate allied republics in its stead, their capitals located at Amphipolis, Thessalonica, Pella, and Pelagonia.[204] The Romans imposed severe laws inhibiting many social and economic interactions between the inhabitants of these republics, including the banning of marriages between them and the (temporary) prohibition on gold and silver mining.[204] A certain Andriscus, claiming Antigonid descent, rebelled against the Romans and was pronounced king of Macedonia, defeating the army of the Roman praetor Publius Juventius Thalna during the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC).[205] Despite this, Andriscus was defeated in 148 BC at the second Battle of Pydna by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, whose forces occupied the kingdom.[206] This was followed in 146 BC by the Roman destruction of Carthage and victory over the Achaean League at the Battle of Corinth, ushering in the era of Roman Greece and the gradual establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia.[207]

Institutions

Division of power

At the head of Macedonia's government was the king (basileus).[note 15] From at least the reign of Philip II, the king was assisted by the royal pages (basilikoi paides), bodyguards (somatophylakes), companions (hetairoi), friends (philoi), an assembly that included members of the military, and (during the Hellenistic period) magistrates.[208] Evidence is lacking regarding the extent to which each of these groups shared authority with the king or if their existence had a basis in a formal constitutional framework.[note 16] Before the reign of Philip II, the only institution supported by textual evidence is the monarchy.[note 17]

Kingship and the royal court

The earliest known government of ancient Macedonia was that of its monarchy, lasting until 167 BC when it was abolished by the Romans.[209] The Macedonian hereditary monarchy existed since at least the time of Archaic Greece, with Homeric aristocratic roots in Mycenaean Greece.[210] Thucydides wrote that in previous ages, Macedonia was divided into small tribal regions, each having its own petty king, the tribes of Lower Macedonia eventually coalescing under one great king who exercised power as an overlord over the lesser kings of Upper Macedonia.[16] The direct line of father-to-son succession was broken after the assassination of Orestes of Macedon in 396 BC (allegedly by his regent and successor Aeropus II of Macedon), clouding the issue of whether primogeniture was the established custom or if there was a constitutional right for an assembly of the army or of the people to choose another king.[211] It is unclear if the male offspring of Macedonian queens or consorts were always preferred over others given the accession of Archelaus I of Macedon, son of Perdiccas II of Macedon and a slave woman, although Archelaus succeeded the throne after murdering his father's designated heir apparent.[212]

It is known that Macedonian kings before Philip II upheld the privileges and carried out the responsibilities of hosting foreign diplomats, determining the kingdom's foreign policies, and negotiating alliances with foreign powers.[213] After the Greek victory at Salamis in 480 BC, the Persian commander Mardonius had Alexander I of Macedon sent to Athens as a chief envoy to orchestrate an alliance between the Achaemenid Empire and Athens. The decision to send Alexander was based on his marriage alliance with a noble Persian house and his previous formal relationship with the city-state of Athens.[213] With their ownership of natural resources including gold, silver, timber, and royal land, the early Macedonian kings were also capable of bribing foreign and domestic parties with impressive gifts.[214]

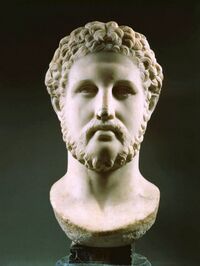

Little is known about the judicial system of ancient Macedonia except that the king acted as the chief judge of the kingdom.[215] The Macedonian kings were also supreme commanders of the military.[note 18] Philip II was also highly regarded for his acts of piety in serving as the high priest of the nation. He performed daily ritual sacrifices and led religious festivals.[216] Alexander imitated various aspects of his father's reign, such as granting land and gifts to loyal aristocratic followers,[216] but lost some core support among them for adopting some of the trappings of an Eastern, Persian monarch, a "lord and master" as Carol J. King suggests, instead of a "comrade-in-arms" as was the traditional relationship of Macedonian kings with their companions.[217] Alexander's father, Philip II, was perhaps influenced by Persian traditions when he adopted institutions similar to those found in the Achaemenid realm, such as having a royal secretary, royal archive, royal pages, and a seated throne.[218]

Royal pages

The royal pages were adolescent boys and young men conscripted from aristocratic households and serving the kings of Macedonia perhaps from the reign of Philip II onward, although more solid evidence dates to the reign of Alexander the Great.[note 19] Royal pages played no direct role in high politics and were conscripted as a means to introduce them to political life.[219] After a period of training and service, pages were expected to become members of the king's companions and personal retinue.[220] During their training, pages were expected to guard the king as he slept, supply him with horses, aid him in mounting his horse, accompany him on royal hunts, and serve him during symposia (i.e. formal drinking parties).[221] Although there is little evidence for royal pages in the Antigonid period, it is known that some of them fled with Perseus of Macedon to Samothrace following his defeat by the Romans in 168 BC.[222]

Bodyguards

Royal bodyguards served as the closest members to the king at court and on the battlefield.[219] They were split into two categories: the agema of the hypaspistai, a type of ancient special forces usually numbering in the hundreds, and a smaller group of men handpicked by the king either for their individual merits or to honor the noble families to which they belonged.[219] Therefore, the bodyguards, limited in number and forming the king's inner circle, were not always responsible for protecting the king's life on and off the battlefield; their title and office was more a mark of distinction, perhaps used to quell rivalries between aristocratic houses.[219]

Companions, friends, councils, and assemblies

The companions, including the elite companion cavalry and pezhetairoi infantry, represented a substantially larger group than the king's bodyguards.[note 20] The most trusted or highest ranking companions formed a council that served as an advisory body to the king.[223] A small amount of evidence suggests the existence of an assembly of the army during times of war and a people's assembly during times of peace.[note 21]

Members of the council had the right to speak freely, and although there is no direct evidence that they voted on affairs of state, it is clear that the king was at least occasionally pressured to agree to their demands.[224] The assembly was apparently given the right to judge cases of high treason and assign punishments for them, such as when Alexander the Great acted as prosecutor in the trial and conviction of three alleged conspirators in his father's assassination plot (while many others were acquitted).[225] However, there is perhaps insufficient evidence to allow a conclusion that councils and assemblies were regularly upheld or constitutionally grounded, or that their decisions were always heeded by the king.[226] At the death of Alexander the Great, the companions immediately formed a council to assume control of his empire, but it was soon destabilized by open rivalry and conflict between its members.[227] The army also used mutiny as a tool to achieve political ends.[note 22]

Magistrates, the commonwealth, local government, and allied states

Antigonid Macedonian kings relied on various regional officials to conduct affairs of state.[228] This included high-ranking municipal officials, such as the military strategos and the politarch, i.e. the elected governor (archon) of a large city (polis), as well as the politico-religious office of the epistates.[note 23] No evidence exists about the personal backgrounds of these officials, although they may have been chosen among the same group of aristocratic philoi and hetairoi who filled vacancies for army officers.[215]

In ancient Athens, the Athenian democracy was restored on three separate occasions following the initial conquest of the city by Antipater in 322 BC.[229] When it fell repeatedly under Macedonian rule it was governed by a Macedonian-imposed oligarchy composed of the wealthiest members of the city-state.[note 24] Other city-states were handled quite differently and were allowed a greater degree of autonomy.[230] After Philip II conquered Amphipolis in 357 BC, the city was allowed to retain its democracy, including its constitution, popular assembly, city council (boule), and yearly elections for new officials, but a Macedonian garrison was housed within the city walls along with a Macedonian royal commissioner (epistates) to monitor the city's political affairs.[231] Philippi, the city founded by Philip II, was the only other city in the Macedonian commonwealth that had a democratic government with popular assemblies, since the assembly (ecclesia) of Thessaloniki seems to have had only a passive function in practice.[232] Some cities also maintained their own municipal revenues.[230] The Macedonian king and central government administered the revenues generated by temples and priesthoods.[233]

Within the Macedonian commonwealth, some evidence from the 3rd century BC indicates that foreign relations were handled by the central government. Although individual Macedonian cities nominally participated in Panhellenic events as independent entities, in reality, the granting of asylia (inviolability, diplomatic immunity, and the right of asylum at sanctuaries) to certain cities was handled directly by the king.[234] Likewise, the city-states within contemporary Greek koina (i.e., federations of city-states, the sympoliteia) obeyed the federal decrees voted on collectively by the members of their league.[note 25] In city-states belonging to a league or commonwealth, the granting of proxenia (i.e. the hosting of foreign ambassadors) was usually a right shared by local and central authorities.[235] Abundant evidence exists for the granting of proxenia as being the sole prerogative of central authorities in the neighboring Epirote League, and some evidence suggests the same arrangement in the Macedonian commonwealth.[236] City-states that were allied with Macedonia issued their own decrees regarding proxenia.[237] Foreign leagues also formed alliances with the Macedonian kings, such as when the Cretan League signed treaties with Demetrius II Aetolicus and Antigonus III Doson ensuring enlistment of Cretan mercenaries into the Macedonian army, and elected Philip V of Macedon as honorary protector (prostates) of the league.[238]

Military

Early Macedonian army

The basic structure of the Ancient Macedonian army was the division between the companion cavalry (hetairoi) and the foot companions (pezhetairoi), augmented by various allied troops, foreign levied soldiers, and mercenaries.[239] The foot companions existed perhaps since the reign of Alexander I of Macedon.[240] Macedonian cavalry, wearing muscled cuirasses, became renowned in Greece during and after their involvement in the Peloponnesian War, at times siding with either Athens or Sparta.[241] Macedonian infantry in this period consisted of poorly trained shepherds and farmers, while the cavalry was composed of noblemen.[242] As evidenced by early 4th century BC artwork, there was a pronounced Spartan influence on the Macedonian army before Philip II.[243] Nicholas Viktor Sekunda states that at the beginning of Philip II's reign in 359 BC, the Macedonian army consisted of 10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry,[244] yet Malcolm Errington cautions that these figures cited by ancient authors should be treated with some skepticism.[245]

Philip II and Alexander the Great

After spending years as a political hostage in Thebes, Philip II sought to imitate the Greek example of martial exercises and the issuing of standard equipment for citizen soldiery, and succeeded in transforming the Macedonian army from a levied force of unprofessional farmers into a well-trained, professional army.[246] Philip II adopted some of the military tactics of his enemies, such as the embolon (flying wedge) cavalry formation of the Scythians.[247] His infantry wielded peltai shields that replaced the earlier aspis-style shields, were equipped with protective helmets, greaves, and either cuirasses breastplates or kotthybos stomach bands, and armed with sarissa pikes and daggers as secondary weapons.[note 26] The elite hypaspistai infantry, composed of handpicked men from the ranks of the pezhetairoi, were formed during the reign of Philip II and saw continued use during the reign of Alexander the Great.[248] Philip II was also responsible for the establishment of the royal bodyguards (somatophylakes).[249]

For his lighter missile troops, Philip II employed mercenary Cretan archers as well as Thracian, Paeonian, and Illyrian javelin throwers, slingers, and archers.[250] He hired engineers such as Polyidus of Thessaly and Diades of Pella, who were capable of building state of the art siege engines and artillery that fired large bolts.[247] Following the acquisition of the lucrative mines at Krinides (renamed Philippi), the royal treasury could afford to field a permanent, professional standing army.[251] The increase in state revenues under Philip II allowed the Macedonians to build a small navy for the first time, which included triremes.[252]

The only Macedonian cavalry units attested under Alexander were the companion cavalry,[249] yet he formed a hipparchia (i.e. unit of a few hundred horsemen) of companion cavalry composed entirely of ethnic Persians while campaigning in Asia.[253] When marching his forces into Asia, Alexander brought 1,800 cavalrymen from Macedonia, 1,800 cavalrymen from Thessaly, 600 cavalrymen from the rest of Greece, and 900 prodromoi cavalry from Thrace.[254] Antipater was able to quickly raise a force of 600 native Macedonian cavalry to fight in the Lamian War when it began in 323 BC.[254] The most elite members of Alexander's hypaspistai were designated as the agema, and a new term for hypaspistai emerged after the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC: the argyraspides (silver shields).[255] The latter continued to serve after the reign of Alexander the Great and may have been of Asian origin.[note 27] Overall, his pike-wielding phalanx infantry numbered some 12,000 men, 3,000 of which were elite hypaspistai and 9,000 of which were pezhetairoi.[note 28] Alexander continued the use of Cretan archers and introduced native Macedonian archers into the army.[256] After the Battle of Gaugamela, archers of West Asian backgrounds became commonplace.[256]

Antigonid period military

The Macedonian army continued to evolve under the Antigonid dynasty. It is uncertain how many men were appointed as somatophylakes, which numbered eight men at the end of Alexander the Great's reign, while the hypaspistai seem to have morphed into assistants of the somatophylakes.[note 29] At the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC, the Macedonians commanded some 16,000 phalanx pikemen.[257] Alexander the Great's royal squadron of companion cavalry contained 800 men, the same number of cavalrymen in the sacred squadron (Latin: sacra ala; Greek: hiera ile) commanded by Philip V of Macedon during the Social War of 219 BC.[258] The regular Macedonian cavalry numbered 3,000 at Callinicus, which was separate from the sacred squadron and royal cavalry.[258] While Macedonian cavalry of the 4th century BC had fought without shields, the use of shields by cavalry was adopted from the Celtic invaders of the 270s BC who settled in Galatia, central Anatolia.[259]

Thanks to contemporary inscriptions from Amphipolis and Greia dated 218 and 181 BC, respectively, historians have been able to partially piece together the organization of the Antigonid army under Philip V.[note 30] From at least the time of Antigonus III Doson, the most elite Antigonid-period infantry were the peltasts, lighter and more maneuverable soldiers wielding peltai javelins, swords, and a smaller bronze shield than Macedonian phalanx pikemen, although they sometimes served in that capacity.[note 31] Among the peltasts, roughly 2,000 men were selected to serve in the elite agema vanguard, with other peltasts numbering roughly 3,000.[260] The number of peltasts varied over time, perhaps never more than 5,000 men.[note 32] They fought alongside the phalanx pikemen, divided now into chalkaspides (bronze shield) and leukaspides (white shield) regiments.[261]

The Antigonid Macedonian kings continued to expand and equip the navy.[262] Cassander maintained a small fleet at Pydna, Demetrius I of Macedon had one at Pella, and Antigonus II Gonatas, while serving as a general for Demetrius in Greece, used the navy to secure the Macedonian holdings in Demetrias, Chalkis, Piraeus, and Corinth.[263] The navy was considerably expanded during the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC), allowing the Macedonian navy to defeat the Ptolemaic Egyptian navy at the 255 BC Battle of Cos and 245 BC Battle of Andros, and enabling Macedonian influence to spread over the Cyclades.[263] Antigonus III Doson used the Macedonian navy to invade Caria, while Philip V sent 200 ships to fight in the Battle of Chios in 201 BC.[263] The Macedonian navy was reduced to a mere six vessels as agreed in the 197 BC peace treaty that concluded the Second Macedonian War with the Roman Republic, although Perseus of Macedon quickly assembled some lemboi at the outbreak of the Third Macedonian War in 171 BC.[263]

Society and culture

Language and dialects

Following its adoption as the court language of Philip II of Macedon's regime, authors of ancient Macedonia wrote their works in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of late Classical and Hellenistic Greece.[note 33] Rare textual evidence indicates that the native Macedonian language was either a dialect of Greek similar to Thessalian Greek and Northwestern Greek,[note 34] or a language closely related to Greek.[note 35] The vast majority of surviving inscriptions from ancient Macedonia were written in Attic Greek and its successor Koine.[264] Attic (and later Koine) Greek was the preferred language of the Ancient Macedonian army, although it is known that Alexander the Great once shouted an emergency order in Macedonian to his royal guards during the drinking party where he killed Cleitus the Black.[265] Macedonian became extinct in either the Hellenistic or the Roman period, and entirely replaced by Koine Greek.[266][note 36]

Religious beliefs and funerary practices

By the 5th century BC, the Macedonians and the southern Greeks worshiped more or less the same deities of the Greek pantheon.[268] In Macedonia, political and religious offices were often intertwined. For instance, the head of state for the city of Amphipolis also served as the priest of Asklepios, Greek god of medicine; a similar arrangement existed at Cassandreia, where a cult priest honoring the city's founder Cassander was the nominal head of the city.[269] The main sanctuary of Zeus was maintained at Dion, while another at Veria was dedicated to Herakles and was patronized by Demetrius II Aetolicus (r. 239–229 BC).[270] Meanwhile, foreign cults from Egypt were fostered by the royal court, such as the temple of Sarapis at Thessaloniki.[271] The Macedonians also had relations with "international" cults; for example, Macedonian kings Philip III of Macedon and Alexander IV of Macedon made votive offerings to the internationally esteemed Samothrace temple complex of the Cabeiri mystery cult.[271]

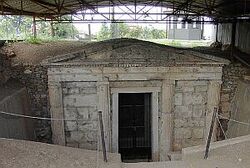

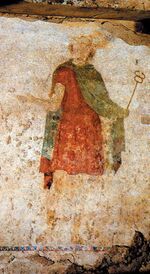

In the three royal tombs at Vergina, professional painters decorated the walls with a mythological scene of Hades abducting Persephone and royal hunting scenes, while lavish grave goods including weapons, armor, drinking vessels, and personal items were housed with the dead, whose bones were burned before burial in golden coffins.[272] Some grave goods and decorations were common in other Macedonian tombs, yet some items found at Vergina were distinctly tied to royalty, including a diadem, luxurious goods, and arms and armor.[273] Scholars have debated about the identity of the tomb occupants since the discovery of their remains in 1977–1978,[274] and recent research and forensic examination have concluded that at least one of the persons buried was Philip II.[note 37] Located near Tomb 1 are the above-ground ruins of a heroon, a shrine for cult worship of the dead.[275] In 2014, the ancient Macedonian Kasta Tomb was discovered outside of Amphipolis and is the largest ancient tomb found in Greece (as of 2017).[276]

Economics and social class

Young Macedonian men were typically expected to engage in hunting and martial combat as a by-product of their transhumance lifestyle of herding livestock such as goats and sheep, while horse breeding and raising cattle were other common pursuits.[277] Some Macedonians engaged in farming, often with irrigation, land reclamation, and horticulture activities supported by the Macedonian state.[note 38] The Macedonian economy and state finances were mainly supported by logging and by mining valuable minerals such as copper, iron, gold, and silver.[278] The conversion of these raw materials into finished products and the sale of those products encouraged the growth of urban centers and a gradual shift away from the traditional rustic Macedonian lifestyle during the course of the 5th century BC.[279]

The Macedonian king was an autocratic figure at the head of both government and society, with arguably unlimited authority to handle affairs of state and public policy, but he was also the leader of a very personal regime with close relationships or connections to his hetairoi, the core of the Macedonian aristocracy.[280] These aristocrats were second only to the king in terms of power and privilege, filling the ranks of his administration and serving as commanding officers in the military.[281] It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the Hellenistic kingdoms that succeeded Alexander the Great's empire where greater social mobility for members of society seeking to join the aristocracy could be found, especially in Ptolemaic Egypt.[282] Although governed by a king and martial aristocracy, Macedonia seems to have lacked the widespread use of slaves seen in contemporaneous Greek states.[283]

Visual arts

By the reign of Archelaus I in the 5th century BC, the ancient Macedonian elite was importing customs and artistic traditions from other regions of Greece while retaining more archaic, perhaps Homeric, funerary rites connected with the symposium that were typified by items such as the decorative metal kraters that held the ashes of deceased Macedonian nobility in their tombs.[284] Among these is the large bronze Derveni Krater from a 4th-century BC tomb of Thessaloniki, decorated with scenes of the Greek god Dionysus and his entourage and belonging to an aristocrat who had had a military career.[285] Macedonian metalwork usually followed Athenian styles of vase shapes from the 6th century BC onward, with drinking vessels, jewellery, containers, crowns, diadems, and coins among the many metal objects found in Macedonian tombs.[286]

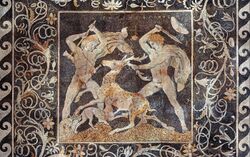

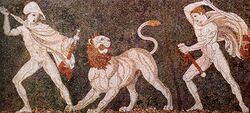

Surviving Macedonian painted artwork includes frescoes and murals, but also decoration on sculpted artwork such as statues and reliefs. For instance, trace colors still exist on the bas-reliefs of the late 4th-century BC Alexander Sarcophagus.[288] Macedonian paintings have allowed historians to investigate the clothing fashions as well as military gear worn by the ancient Macedonians.[289] Aside from metalwork and painting, mosaics are another significant form of surviving Macedonian artwork.[286] The Stag Hunt Mosaic of Pella, with its three-dimensional qualities and illusionist style, show clear influence from painted artwork and wider Hellenistic art trends, although the rustic theme of hunting was tailored to Macedonian tastes.[290] The similar Lion Hunt Mosaic of Pella illustrates either a scene of Alexander the Great with his companion Craterus, or simply a conventional illustration of the royal diversion of hunting.[290] Mosaics with mythological themes include scenes of Dionysus riding a panther and Helen of Troy being abducted by Theseus, the latter of which employs illusionist qualities and realistic shading similar to Macedonian paintings.[290] Common themes of Macedonian paintings and mosaics include warfare, hunting, and aggressive masculine sexuality (i.e. abduction of women for rape or marriage); these subjects are at times combined within a single work and perhaps indicate a metaphorical connection.[note 39]

Theatre, music and performing arts

Philip II was assassinated in 336 BC at the theatre of Aigai, amid games and spectacles celebrating the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra.[291] Alexander the Great was allegedly a great admirer of both theatre and music.[292] He was especially fond of the plays by Classical Athenian tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, whose works formed part of a proper Greek education for his new eastern subjects alongside studies in the Greek language, including the epics of Homer.[293] While he and his army were stationed at Tyre (in modern-day Lebanon), Alexander had his generals act as judges not only for athletic contests but also for stage performances of Greek tragedies.[294] The contemporaneous famous actors Thessalus and Athenodorus performed at the event.[note 40]

Music was also appreciated in Macedonia. In addition to the agora, the gymnasium, the theatre, and religious sanctuaries and temples dedicated to Greek gods and goddesses, one of the main markers of a true Greek city in the empire of Alexander the Great was the presence of an odeon for musical performances.[295] This was the case not only for Alexandria in Egypt, but also for cities as distant as Ai-Khanoum in what is now modern-day Afghanistan.[295]

Literature, education, philosophy, and patronage