Biology:Eel

Eels are ray-finned fish belonging to the order Anguilliformes (/æŋˈɡwɪlɪfɔːrmiːz/), which consists of eight suborders, 20 families, 164 genera, and about 1000 species.[1][2] Eels undergo considerable development from the early larval stage to the eventual adult stage and are usually predators.

The term "eel" is also used for some other eel-shaped fish, such as electric eels (genus Electrophorus), swamp eels (order Synbranchiformes), and deep-sea spiny eels (family Notacanthidae). However, these other clades, with the exception of deep-sea spiny eels, whose order Notacanthiformes is the sister clade to true eels, evolved their eel-like shapes independently from the true eels. As a main rule, most eels are marine. Exceptions are the catadromous genus Anguilla and the freshwater moray,[3] which spend most of their life in freshwater, the anadromous rice-paddy eel, which spawns in freshwater, and the freshwater snake eel Stictorhinus.[4]

Description

File:Gymnothorax isingteena - spotted moray eel - aug 29 2016.webmEels are elongated fish, ranging in length from 5 cm (2 in) in the one-jawed eel (Monognathus ahlstromi) to 4 m (13 ft) in the slender giant moray.[5] Adults range in weight from 30 g (1 oz) to well over 25 kg (55 lb). They possess no pelvic fins, and many species also lack pectoral fins. The dorsal and anal fins are fused with the caudal fin, forming a single ribbon running along much of the length of the animal.[6] Eels swim by generating waves that travel the length of their bodies. They can swim backward by reversing the direction of the wave.[7]

Most eels live in the shallow waters of the ocean and burrow into sand, mud, or amongst rocks. Most eel species are nocturnal, and thus are rarely seen. Sometimes, they are seen living together in holes or "eel pits". Some eels also live in deeper water on the continental shelves and over the slopes deep as 4,000 m (13,000 ft). Only members of the Anguilla regularly inhabit fresh water, but they, too, return to the sea to breed.[8]

The heaviest true eel is the European conger. The maximum size of this species has been reported as reaching a length of 3 m (10 ft) and a weight of 110 kg (240 lb).[9] Other eels are longer, but do not weigh as much, such as the slender giant moray, which reaches 4 m (13 ft).[10]

Life cycle

Eels begin life as flat and transparent larvae, called leptocephali. Eel larvae drift in the sea's surface waters, feeding on marine snow, small particles that float in the water. Eel larvae then metamorphose into glass eels and become elvers before finally seeking out their juvenile and adult habitats.[5] Some individuals of anguillid elvers remains in brackish and marine areas close to coastlines,[11] but most of them enter freshwater where they travel upstream and are forced to climb up obstructions, such as weirs, dam walls, and natural waterfalls.

-

Eel eggs hatch firstly into the leptocephalus larval stage.

-

Larval eels become glass eels as they transition from the ocean to fresh water.

-

As freshwater elvers, eels work their way upstream.

-

Mature silver stage eels migrate back to the ocean to mate.

Gertrude Elizabeth Blood found that the eel fisheries at Ballisodare were greatly improved by the hanging of loosely plaited grass ladders over barriers, enabling elvers to ascend more easily.[12]

Classification

Template:Common fish Several sets of classifications of eels exist; some, such as FishBase which divide eels into 20 families, whereas other classification systems such as ITIS and Systema Naturae 2000 include additional eel families, which are noted below.

Genomic studies indicate that there is a monophyletic group that originated among the deep-sea eels.[13]

Taxonomy

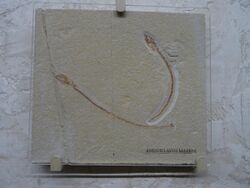

The earliest fossil eels are known from the Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Lebanon. These early eels retain primitive traits such as pelvic fins and thus do not appear to be closely related to any extant taxa. Body fossils of modern eels do not appear until the Eocene, although otoliths assignable to extant eel families and even some genera have been recovered from the Campanian and Maastrichtian, indicating some level of diversification among the extant groups prior to the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, which is also supported by phylogenetic divergence estimates. One of these otolith taxa, the mud-dwelling Pythonichthys arkansasensis, appears to have thrived in the aftermath of the K-Pg extinction, based on its abundance.[14][15][16]

Extant taxa

Taxonomy based on Eschmeyer's Catalog of Fishes:[17]

Order Anguilliformes

- Suborder Chlopsoidei

- Family Chlopsidae Rafinesque, 1815 (false morays)

- Suborder Synaphobranchoidei

- Family Protanguillidae G. D. Johnson, Ida & Miya, 2011 (primitive cave eels)

- Family Synaphobranchidae J. Y. Johnson, 1862 (cutthroat eels)

- Subfamily Simenchelyinae Gill, 1879 (pugnose parasitic eels)

- Subfamily Ilyophinae D. S. Jordan & Davis, 1891 (arrowtooth eels or mustard eels)

- Subfamily Synaphobranchinae J. Y. Johnson, 1862 (cutthroat eels)

- Suborder Anguilloidei

- Family Moringuidae Gill, 1885 (spaghetti eels)

- Family Anguillidae Rafinesque, 1810 (freshwater eels)

- Family Nemichthyidae Kaup. 1859 (snipe eels or threadtail snipe eels)

- Family Serrivomeridae Trewavas, 1932 (sawtooth eels)

- Family Cyematidae Regan, 1912 (bobtail eels)

- Family Monognathidae Trewavas, 1937 (onejaw gulpers)

- Family Neocyematidae Poulsen, M. J. Miller, Sado, Hanel, Tsukamoto & Miya, 2018 (orange bobtail eels)

- Family Eurypharyngidae Gill, 1883 (gulper eels or pelican eels)

- Family Saccopharyngidae Bleeker, 1859 (swallower eels or whiptail gulpers)

- Suborder Muraenoidei

- Family Heterenchelyidae Regan, 1912 (mud eels)

- Family Myrocongridae Gill, 1890 (myroconger eels)

- Family Muraenidae Rafinesque, 1815 (moray eels)

- Subfamily Uropterygiinae Fowler, 1925 (tailfin moray eels)

- Subfamily Muraeninae Rafinesque, 1815 (morays)

- Suborder Congroidei

- Family Colocongridae Smith, 1976 (shorttail eels)

- Family Derichthyidae Gill, 1884 (longneck eels or narrowneck eels)

- Family Ophichthidae Günther, 1870 (snake eels and worm eels)

- Subfamily Myrophinae Kaup, 1856 (worm eels)

- Subfamily Ophichthinae Günther, 1870 (snake eels)

- Family Muraenesocidae Kaup, 1859 (pike conger eels)

- Family Nettastomatidae Kaup, 1859 (duckbill eels)

- Family Congridae Kaup, 1856 (conger eels)

- Subfamily Congrinae Kaup, 1856 (congers)

- Subfamily Bathymyrinae Böhlke, 1949

- Subfamily Heterocongrinae Günther, 1870 (garden eels)

-

Anguilla anguilla (Anguillidae)

-

Kaupichthys nuchalis (Chlopsidae)

-

Coloconger raniceps (Colocongridae)

-

Conger cinereus (Congridae)

-

Muraenesox cinereus (Muraenesocidae)

-

Echidna nebulosa (Muraenidae)

-

Myrichthys ocellatus (Ophichthidae)

-

Serrivomer sp. (Serrivomeridae)

In some classifications, the family Cyematidae of bobtail snipe eels is included in the Anguilliformes, but in the FishBase system that family is included in the order Saccopharyngiformes.

The electric eel of South America is not a true eel but is a South American knifefish more closely related to the carps and catfishes.[18]

Phylogeny

Phylogeny based on Johnson et al. 2012.[19]

| Anguilliformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extinct taxa

Based on the Paleobiology Database:[20][21]

- Genus †Abisaadia

- Genus †Bolcanguilla

- Genus †Eomuraena

- Genus †Eomyrophis

- Genus †Gazolapodus

- Genus †Hayenchelys

- Genus †Luenchelys

- Genus †Mastygocercus

- Genus †Micromyrus

- Genus †Mylomyrus

- Genus †Palaeomyrus

- Genus †Parechelus

- Genus †Proserrivomer

- Family †Anguillavidae

- Family †Anguilloididae

- Family †Libanechelyidae

- Family †Milananguillidae

- Family †Paranguillidae

- Family †Patavichthyidae

- Family †Proteomyridae

- Family †Urenchelyidae

Commercial species

| Main commercial species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

FishBase | FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| American eel | Anguilla rostrata (Lesueur, 1817) | 152 cm | 50 cm | 7.33 kg | 43 years | 3.7 | [22] | [23] | EN IUCN 3 1.svg Endangered[24] | |

| European eel | Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758) | 150 cm | 35 cm | 6.6 kg | 88 years | 3.5 | [25] | [26] | [27] | CR IUCN 3 1.svg Critically endangered[28] |

| Japanese eel | Anguilla japonica (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) | 150 cm | 40 cm | 1.89 kg | 3.6 | [29] | [30] | [31] | EN IUCN 3 1.svg Endangered[32] | |

| Short-finned eel | Anguilla australis (Richardson, 1841) | 130 cm | 45 cm | 7.48 kg | 32 years | 4.1 | [33] | [34] | EN IUCN 3 1.svg Near Threatened[35] | |

Use by humans

Freshwater eels (unagi) and marine eels (conger eel, anago) are commonly used in Japanese cuisine; foods such as unadon and unajū are popular, but expensive. Eels are also very popular in Chinese cuisine, and are prepared in many different ways. Hong Kong eel prices have often reached 1000 HKD (128.86 US Dollars) per kg, and once exceeded 5000 HKD per kg. In India, eels are popularly eaten in the Northeast. Freshwater eels, known as Kusia in Assamese, are eaten with curry,[36] often with herbs.[37] The European eel and other freshwater eels are mostly eaten in Europe and the United States, and is considered critically endangered.[38] A traditional east London food is jellied eels, although the demand has significantly declined since World War II. The Spanish cuisine delicacy angulas consists of elver (young eels) sautéed in olive oil with garlic; elvers usually reach prices of up to 1000 euro per kg.[39] New Zealand longfin eel is a traditional Māori food in New Zealand. In Italian cuisine, eels from the Valli di Comacchio, a swampy zone along the Adriatic coast, are especially prized, along with freshwater eels of Bolsena Lake and pond eels from Cabras, Sardinia. In northern Germany, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Poland, Denmark, and Sweden, smoked eel is considered a delicacy.

Elvers, often fried, were once a cheap dish in the United Kingdom. During the 1990s, their numbers collapsed across Europe.[40] They became a delicacy, and the UK's most expensive species.[41]

Eels, particularly the moray eel, are popular among marine aquarists.

Eel blood is toxic to humans[42] and other mammals,[43][44][45] but both cooking and the digestive process destroy the toxic protein.

High consumption of eels is seen in European countries leading to those eel species being considered endangered.

Sustainable consumption

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the European eel, Japanese eel, and American eel to its seafood red list.[46] Japan consumes more than 70% of the global eel catch.[47]

-

Eel fishing boat in France

-

Special boats to transport live eels Comacchio

-

Eel trap in Denmark around 1900

-

Gerookte paling (Dutch for smoked eel)

Etymology

The English name "eel" descends from Old English ǣl, Common Germanic *ēlaz. Also from the common Germanic are West Frisian iel, Dutch aal, German Aal, and Icelandic áll. Katz (1998) identifies a number of Indo-European cognates, among them the second part of the Latin word for eels, anguilla, attested in its simplex form illa (in a glossary only), and the Greek word for "eel", ἔγχελυς enkhelys (the second part of which is attested in Hesychius as elyes).[48][49][50] The first compound member, anguis ("snake"), is cognate to other Indo-European words for "snake" (compare Old Irish escung "eel", Old High German unc "snake", Lithuanian angìs, Greek ophis, okhis, Vedic Sanskrit áhi, Avestan aži, Armenian auj, iž, Old Church Slavonic *ǫžь, all from Proto-Indo-European *h₁ogʷʰis). The word also appears in the Old English word for "hedgehog", which is igil (meaning "snake eater"), and perhaps in the egi- of Old High German egidehsa "wall lizard".[51][52]

According to this theory, the name Bellerophon (Βελλεροφόντης, attested in a variant Ἐλλεροφόντης in Eustathius of Thessalonica) is also related, translating to "the slayer of the serpent" (ahihán). In this theory, the ελλερο- is an adjective form of an older word, ελλυ, meaning "snake", which is directly comparable to Hittite ellu-essar- "snake pit". This myth likely came to Greece via Anatolia. In the Hittite version of the myth, the dragon is called Illuyanka: the illuy- part is cognate to the word illa, and the -anka part is cognate to angu, a word for "snake". Since the words for "snake" (and similarly shaped animals) are often subject to taboo in many Indo-European (and non-Indo-European) languages, no unambiguous Proto-Indo-European form of the word for eel can be reconstructed. It may have been *ēl(l)-u-, *ēl(l)-o-, or something similar.

Timeline of genera

| Timeline |

|---|

| <timeline>

ImageSize = width:800px height:auto barincrement:15px PlotArea = left:10px bottom:50px top:10px right:10px Period = from:-145.5 till:25 TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:10 start:-145.5 ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:1 start:-145.5 TimeAxis = orientation:hor AlignBars = justify Colors = #legends id:CAR value:claret id:ANK value:rgb(0.4,0.3,0.196) id:HER value:teal id:HAD value:green id:OMN value:blue id:black value:black id:white value:white id:cretaceous value:rgb(0.5,0.78,0.31) id:earlycretaceous value:rgb(0.63,0.78,0.65) id:latecretaceous value:rgb(0.74,0.82,0.37) id:cenozoic value:rgb(0.54,0.54,0.258) id:paleogene value:rgb(0.99,0.6,0.32) id:paleocene value:rgb(0.99,0.65,0.37) id:eocene value:rgb(0.99,0.71,0.42) id:oligocene value:rgb(0.99,0.75,0.48) id:neogene value:rgb(0.999999,0.9,0.1) id:miocene value:rgb(0.999999,0.999999,0) id:pliocene value:rgb(0.97,0.98,0.68) id:quaternary value:rgb(0.98,0.98,0.5) id:pleistocene value:rgb(0.999999,0.95,0.68) id:holocene value:rgb(0.999,0.95,0.88) BarData= bar:eratop bar:space bar:periodtop bar:space bar:NAM1 bar:NAM2 bar:NAM3 bar:NAM4 bar:NAM5 bar:NAM6 bar:NAM7 bar:NAM8 bar:NAM9 bar:NAM10 bar:NAM11 bar:NAM12 bar:NAM13 bar:NAM14 bar:NAM15 bar:NAM16 bar:NAM17 bar:NAM18 bar:NAM19 bar:NAM20 bar:NAM21 bar:NAM22 bar:NAM23 bar:NAM24 bar:NAM25 bar:NAM26 bar:NAM27 bar:NAM28 bar:NAM29 bar:NAM30 bar:NAM31 bar:NAM32 bar:NAM33 bar:NAM34 bar:NAM35 bar:NAM36 bar:NAM37 bar:NAM38 bar:NAM39 bar:NAM40 bar:NAM41 bar:NAM42 bar:NAM43 bar:NAM44 bar:NAM45 bar:NAM46 bar:NAM47 bar:NAM48 bar:NAM49 bar:NAM50 bar:NAM51 bar:NAM52 bar:NAM53 bar:NAM54 bar:NAM55 bar:NAM56 bar:NAM57 bar:NAM58 bar:NAM59 bar:NAM60 bar:NAM61 bar:NAM62 bar:NAM63 bar:NAM64 bar:NAM65 bar:NAM66 bar:NAM67 bar:NAM68 bar:NAM69 bar:NAM70 bar:NAM71 bar:NAM72 bar:space bar:period bar:space bar:era PlotData= align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25 shift:(7,-4) bar:periodtop from: -145.5 till: -99.6 color:earlycretaceous text:Early from: -99.6 till: -65.5 color:latecretaceous text:Late from: -65.5 till: -55.8 color:paleocene text:Paleo. from: -55.8 till: -33.9 color:eocene text:Eo. from: -33.9 till: -23.03 color:oligocene text:Oligo. from: -23.03 till: -5.332 color:miocene text:Mio. from: -5.332 till: -2.588 color:pliocene text:Pl. from: -2.588 till: -0.0117 color:pleistocene text:Pl. from: -0.0117 till: 0 color:holocene text:H. bar:eratop from: -145.5 till: -65.5 color:cretaceous text:Cretaceous from: -65.5 till: -23.03 color:paleogene text:Paleogene from: -23.03 till: -2.588 color:neogene text:Neogene from: -2.588 till: 0 color:quaternary text:Q. PlotData= align:left fontsize:M mark:(line,white) width:5 anchor:till align:left color:earlycretaceous bar:NAM2 from:-112 till:-99.6 text:Casierius color:latecretaceous bar:NAM3 from:-99.6 till:-89.3 text:Dinelops color:latecretaceous bar:NAM4 from:-99.6 till:-83.5 text:Lebonichthyes color:latecretaceous bar:NAM5 from:-99.6 till:-70.6 text:Enchelurus color:latecretaceous bar:NAM6 from:-95.5 till:-93.5 text:Anguillavus color:latecretaceous bar:NAM7 from:-95.5 till:-93.5 text:Enchelion color:latecretaceous bar:NAM8 from:-95.5 till:-93.5 text:Haljulia color:latecretaceous bar:NAM9 from:-95.5 till:-83.5 text:Urenchelys color:latecretaceous bar:NAM10 from:-85.8 till:-70.6 text:Istieus color:latecretaceous bar:NAM14 from:-83.5 till:0 text:Pterothrissus color:latecretaceous bar:NAM15 from:-70.6 till:-65.5 text:Coriops color:latecretaceous bar:NAM16 from:-70.6 till:-55.8 text:Eodiaphyodus color:paleocene bar:NAM17 from:-65.5 till:-61.7 text:Pseudoegertonia color:paleocene bar:NAM18 from:-65.5 till:-48.6 text:Phyllodus color:eocene bar:NAM19 from:-55.8 till:-48.6 text:Eomuraena color:eocene bar:NAM20 from:-55.8 till:-48.6 text:Micromyrus color:eocene bar:NAM21 from:-55.8 till:-48.6 text:Palaeomyrus color:eocene bar:NAM22 from:-55.8 till:-48.6 text:Parechelus color:eocene bar:NAM23 from:-55.8 till:-48.6 text:Rhynchorinus color:eocene bar:NAM24 from:-55.8 till:-37.2 text:Egertonia color:eocene bar:NAM25 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Anguilloides color:eocene bar:NAM26 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Bolcyrus color:eocene bar:NAM27 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Dalpiazella color:eocene bar:NAM28 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Eoanguilla color:eocene bar:NAM29 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Eomyrus color:eocene bar:NAM30 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Goslinophis color:eocene bar:NAM31 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Milananguilla color:eocene bar:NAM32 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Mylomyrus color:eocene bar:NAM33 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Paracongroides color:eocene bar:NAM34 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Paranguilla color:eocene bar:NAM35 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Patavichthys color:eocene bar:NAM36 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Proteomyrus color:eocene bar:NAM37 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Veronanguilla color:eocene bar:NAM38 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Voltaconger color:eocene bar:NAM39 from:-55.8 till:-33.9 text:Whitapodus color:eocene bar:NAM40 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Anguilla color:eocene bar:NAM41 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Conger color:eocene bar:NAM42 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Gnathophis color:eocene bar:NAM43 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Hoplunnis color:eocene bar:NAM44 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Muraenesox color:eocene bar:NAM45 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Paraconger color:eocene bar:NAM46 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Hildebrandia color:eocene bar:NAM47 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Nettastoma color:eocene bar:NAM48 from:-55.8 till:0 text:Notacanthus color:eocene bar:NAM49 from:-48.6 till:-37.2 text:Bolcanguilla color:eocene bar:NAM50 from:-48.6 till:-37.2 text:Gazolapodus color:eocene bar:NAM51 from:-48.6 till:0 text:Eomyrophis color:eocene bar:NAM52 from:-37.2 till:0 text:Pseudophichthyes color:eocene bar:NAM53 from:-37.2 till:0 text:Rhechias color:oligocene bar:NAM54 from:-33.9 till:-28.4 text:Proserrivomer color:oligocene bar:NAM55 from:-33.9 till:0 text:Ariosoma color:oligocene bar:NAM56 from:-33.9 till:0 text:Myroconger color:oligocene bar:NAM57 from:-28.4 till:0 text:Taenioconger color:miocene bar:NAM58 from:-23.03 till:0 text:Echelus color:miocene bar:NAM59 from:-23.03 till:0 text:Mystriophis color:miocene bar:NAM60 from:-23.03 till:0 text:Uroconger color:miocene bar:NAM61 from:-23.03 till:0 text:Mastygocercus color:miocene bar:NAM62 from:-15.97 till:0 text:Ophisurus color:miocene bar:NAM63 from:-15.97 till:0 text:Panturichthys color:miocene bar:NAM64 from:-15.97 till:0 text:Pisodonophis color:miocene bar:NAM65 from:-15.97 till:0 text:Rhynchoconger color:miocene bar:NAM66 from:-15.97 till:0 text:Scalanago color:miocene bar:NAM67 from:-11.608 till:-5.332 text:Deprandus color:miocene bar:NAM68 from:-11.608 till:-5.332 text:Laytonia color:miocene bar:NAM69 from:-11.608 till:0 text:Muraena color:pliocene bar:NAM70 from:-5.332 till:0 text:Japonoconger color:pliocene bar:NAM71 from:-5.332 till:0 text:Pseudoxenomystax color:pleistocene bar:NAM72 from:-2.588 till:-0.0117 text:Rhynchocymba PlotData= align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25 bar:period from: -145.5 till: -99.6 color:earlycretaceous text:Early from: -99.6 till: -65.5 color:latecretaceous text:Late from: -65.5 till: -55.8 color:paleocene text:Paleo. from: -55.8 till: -33.9 color:eocene text:Eo. from: -33.9 till: -23.03 color:oligocene text:Oligo. from: -23.03 till: -5.332 color:miocene text:Mio. from: -5.332 till: -2.588 color:pliocene text:Pl. from: -2.588 till: -0.0117 color:pleistocene text:Pl. from: -0.0117 till: 0 color:holocene text:H. bar:era from: -145.5 till: -65.5 color:cretaceous text:Cretaceous from: -65.5 till: -23.03 color:paleogene text:Paleogene from: -23.03 till: -2.588 color:neogene text:Neogene from: -2.588 till: 0 color:quaternary text:Q. </timeline> |

In culture

The large lake of Almere, which existed in the early Medieval Netherlands, got its name from the eels which lived in its water (the Dutch word for eel is aal or ael, so: "ael mere" = "eel lake"). The name is preserved in the new city of Almere in Flevoland, given in 1984 in memory of this body of water on whose site the town is located.

The daylight passage in the spring of elvers upstream along the Thames was at one time called "eel fare". The word 'elver' is thought to be a corruption of "eel fare".[12]

A famous attraction on the French Polynesian island of Huahine (part of the Society Islands) is the bridge across a stream hosting three- to six-foot-long eels, deemed sacred by local culture.

Eel fishing in Nazi-era Danzig plays an important role in Günter Grass' novel The Tin Drum. The cruelty of humans to eels is used as a metaphor for Nazi atrocities, and the sight of eels being killed by a fisherman triggers the madness of the protagonist's mother.

Sinister implications of eels fishing are also referenced in Jo Nesbø's Cockroaches, the second book of the Harry Hole detective series. The book's background includes a Norwegian village where eels in the nearby sea are rumored to feed on the corpses of drowned humans, making the eating of these eels verge on cannibalism.

The 2019 book The Gospel of the Eels by Patrick Svensson commented on the 'eel question' (origins of the order) and its cultural history.

See also

- Elver pass

References

- ↑ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Anguilliformes". https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=10295.

- ↑ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Saccopharyngiformes". https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=10296.

- ↑ Ebner, Brendan C.; Donaldson, James A.; Courtney, Robert; Fitzpatrick, Richard; Starrs, Danswell; Fletcher, Cameron S.; Seymour, Jamie (23 September 2019). "Averting danger under the bridge: video confirms that adult small-toothed morays tolerate salinity before and during tidal influx". Pacific Conservation Biology 26 (2): 182–189. doi:10.1071/PC19023. https://www.publish.csiro.au/pc/PC19023.

- ↑ "Family OPHICHTHIDAE". https://etyfish.org/ETYFish_Ophichthidae.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 McCosker, John F. (1998). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 86–90. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Anguilliformes" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

- ↑ Long Jr, J. H., Shepherd, W., & Root, R. G. (Loot). Manueuverability and reversible propulsion: How eel-like fish swim forward and backward using travelling body waves". In: Proc. Special Session on Bio-Engineering Research Related to Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, 10th Int. Symp. (pp. 118–134).

- ↑ Prosek, James (2010). Eels: An Exploration. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-056611-1.

- ↑ Conger conger, European conger: fisheries, gamefish, aquarium. Fishbase.org

- ↑ FishBase . FishBase (15 November 2011).

- ↑ Arai, Takaomi (1 October 2020). "Ecology and evolution of migration in the freshwater eels of the genus Anguilla Schrank, 1798". Heliyon 6 (10). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05176. PMID 33083623. Bibcode: 2020Heliy...605176A.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Campbell, Lady Colin (1886). A Book of the Running Brook: and of Still Waters. New York: O. Judd Co.. pp. 9; 18. https://archive.org/details/abookrunningbro00campgoog.

- ↑ Inoue, Jun G. (2010). "Deep-ocean origin of the freshwater eels". Biol. Lett. 6 (3): 363–366. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0989. PMID 20053660.

- ↑ Pfaff, Cathrin; Zorzin, Roberto; Kriwet, Jürgen (2016-08-11). "Evolution of the locomotory system in eels (Teleostei: Elopomorpha)". BMC Evolutionary Biology 16 (1): 159. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0728-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMID 27514517. Bibcode: 2016BMCEE..16..159P.

- ↑ Near, Thomas J; Thacker, Christine E (18 April 2024). "Phylogenetic classification of living and fossil ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii)". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 65. doi:10.3374/014.065.0101. Bibcode: 2024BPMNH..65..101N.

- ↑ Schwarzhans, Werner W.; Jagt, John W. M. (2021-11-01). "Silicified otoliths from the Maastrichtian type area (Netherlands, Belgium) document early gadiform and perciform fishes during the Late Cretaceous, prior to the K/Pg boundary extinction event". Cretaceous Research 127. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104921. ISSN 0195-6671. Bibcode: 2021CrRes.12704921S.

- ↑ "Eschmeyer's Catalog of Fishes Classification". California Academy of Sciences. https://www.calacademy.org/scientists/catalog-of-fishes-classification.

- ↑ Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W. N.; Van der Laan, R. (2025). "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: CLASSIFICATION" (in en). https://www.calacademy.org/eschmeyers-catalog-of-fishes-classification.

- ↑ Johnson, G. D.; Ida H.; Sakaue J.; Sado T.; Asahida T.; Miya M. (2012). "A 'living fossil' eel (Anguilliformes: Protanguillidae, fam nov) from an undersea cave in Palau". Proceedings of the Royal Society (in press) (1730): 934–943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1289. PMID 21849321.

- ↑ "PBDB". https://paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=35343.

- ↑ Pfaff, Cathrin; Zorzin, Roberto; Kriwet, Jürgen (2016-08-11). "Evolution of the locomotory system in eels (Teleostei: Elopomorpha)". BMC Evolutionary Biology 16 (1): 159. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0728-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMID 27514517. Bibcode: 2016BMCEE..16..159P.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Anguilla rostrata" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Anguilla rostrata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161127.

- ↑ Jacoby, D.; Casselman, J.; DeLucia, M.; Gollock, M. (2017). "Anguilla rostrata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T191108A121739077.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/191108/121739077. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Anguilla anguilla" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ "Anguilla anguilla". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161128.

- ↑ Pike, C.; Crook, V.; Gollock, M. (2020). "Anguilla anguilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T60344A152845178.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/60344/152845178. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Anguilla japonica" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ Anguilla japonica, Temminck & Schlegel, 1846 FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 2012.

- ↑ "Anguilla japonica". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161134.

- ↑ Jacoby, D.; Gollock, M. (2014). "Anguilla japonica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T166184A1117791.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/166184/1117791. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Anguilla australis" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Anguilla australis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161133.

- ↑ Pike, C.; Crook, V.; Gollock, M. (2019). "Anguilla australis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T195502A154801652.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/195502/154801652. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Swamp Eels". https://eol.org/pages/5070/articles.

- ↑ Bhuyan, Avantika (30 March 2018). "The little fish in big rivers". https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/TB9AouNDcXASwUdc7ObL3H/The-little-fish-in-big-rivers.html.

- ↑ Acou, Anthony, et al. "Assessment of the Quality of European Silver Eels and Tentative Approach to Trace the Origin of Contaminants – A European Overview." The science of the total environment. 743 (2020): n. pag. Web.

- ↑ "Buber's Basque Page: Angulas". http://www.buber.net/Basque/Food/food1.html.

- ↑ Champken, Neil (2 June 2006). "Would you pay £600 for a handful of baby eels?". https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2006/jun/02/foodanddrink.features11.

- ↑ Leake, Jonathan (7 February 2015). "EU's eel edict costs UK £100m". The Sunday Times. http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/article1516718.ece.

- ↑ "Poison in the Blood of the Eel". The New York Times. 9 April 1899. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1899/04/09/100439047.html?pageNumber=23.

- ↑ "The plight of the eel (mentions that "Only 0.1 ml/kg is enough to kill small mammals, such as a rabbit...". BBC online. https://www.bbc.co.uk/lincolnshire/content/articles/2006/12/19/angling_eels_feature.shtml.

- ↑ "Blood serum of the eel." M. Sato. Nippon Biseibutsugakukai Zasshi (1917), 5 (No. 35), From: Abstracts Bact. 1, 474 (1917)

- ↑ "Hemolytic and toxic properties of certain serums." Wm. J. Keffer, Albert E. Welsh. Mendel Bulletin (1936), 8 76–80.

- ↑ "Greenpeace Seafood Red list". Greenpeace International. http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/oceans/which-fish-can-I-eat/red-list-of-species/.

- ↑ "Indonesia eel hot item for smugglers". The Japan Times. 29 July 2013. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/07/29/national/indonesia-eel-hot-item-for-smugglers/#.Ufcwixb1s08.

- ↑ Katz, J. (1998). "How to be a Dragon in Indo-European: Hittite illuyankas and its Linguistic and Cultural Congeners in Latin, Greek, and Germanic". in Jasanoff; Melchert; Oliver. Mír Curad. Studies in Honor of Calvert Watkins. Innsbruck. pp. 317–334. ISBN 3-85124-667-5.

- ↑ anguilla. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project..

- ↑ ἔγχελυς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Arai, Takaomi (22 February 2016). Biology and Ecology of Anguillid Eels. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-5516-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=w5umCwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Ross, Stephen T.; Brenneman, William Max (2001). The Inland Fishes of Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-246-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=WEaKXWRt10kC.

Further references

- Tesch FW and White RJ (2008). The Eel. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405173438.

- Patrik Svensson (2019). The Book of Eels, English translation (2020) by Agnes Broomé, published by ecco, ISBN 9780062968814.

External links

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2006). "Anguilliformes" in FishBase. January 2006 version.

- "Anguilliformes". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161123.

"Apodes". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Apodes". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.- "The Natural History of the Eel", historical aspect, Scientific American, 10 August 1878, Vol. 39, No. 6, p. 79

Template:Actinopterygii Wikidata ☰ Q128685 entry

|