Place:Roman temple of Bziza

| Roman temple of Bziza | |

|---|---|

| Native name Arabic: معبد بزيزا | |

Temple of Azizos in Bziza | |

| Location | Bziza, North Lebanon |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 34°16′12″N 35°49′18″E / 34.2699°N 35.8216°E |

| Built | 1st century AD |

| Built for | Azizos |

| Architectural style(s) | Ionic order, Roman |

| <mapframe zoom="10" frameless="1" align="center" longitude="35.8216" latitude="34.2699" height="200" width="270">{"type":"Feature","geometry":{"coordinates":[35.8216,34.2699],"type":"Point"},"properties":{"title":"Roman temple of Bziza","marker-color":"#5E74F3"}}</mapframe> | |

The Roman temple of Bziza is a well-preserved first century AD building dedicated to Azizos, a personification of the morning star in ancient Arab polytheism. This Roman temple lends the modern Lebanese town of Bziza its current name, as Bziza is a corruption of Beth Azizo meaning the house or temple of Azizos. Azizos was identified as Ares by Emperor Julian.

The tetrastyle prostyle building has two doors that connect the pronaos to a square cella. To the back of the temple lie the remains of the adyton where images of the deity once stood. The ancient temple functioned as an aedes, the dwelling place of the deity. The temple of Bziza was converted into a church and underwent architectural modification during two phases of Christianization; in the Early Byzantine period and later in the Middle Ages. The church, colloquially known until modern times as the Lady of the Pillars, fell into disrepair. Despite the church's condition, Christian devotion was still maintained in the nineteenth century in one of the temple's niches. The temple of Bziza is featured on multiple stamps issued by the Lebanese state.

History

Historical background

In 64 BC, the Roman general Pompey annexed Phoenicia to the Roman province of Syria after years of disorderly power vacuum caused by the Seleucid dynastic wars.[1][2] In his treatise on Phoenician history, Byblian writer Philo maintained that the gods and goddesses venerated in Phoenicia were Hellenized Phoenician deities.[3] The wave of cultural Hellenization created pan-Phoenician patriotism and a deeper attachment to pre-Hellenic religious traditions.[3] Phoenician devotion to ancient gods continued under Roman rule as described in the De dea Syria [On the Syrian Goddess] treatise by second century AD rhetor Lucian of Samosata. Lucian visited sacred cities of Syria, Phoenicia and the Libanus where numerous mountain sanctuaries were spreading all over the countryside.[4][5] Temple building, urbanization and monumentalization of cities was financed by generous endowments of client kings and wealthy citizens seeking to increase their power and sphere of influence. The prosperity of Roman Phoenicia was in turn fueled by maritime export and the elevation of numerous Phoenician cities to the status of Roman colony,[a] giving the inhabitants Roman citizenship.[6]

Construction

The temple of Bziza was built during the Julio-Claudian dynasty in the first century AD, at a time when Roman hegemony over the region was still being consolidated.[7] The Phoenicians perpetuated the ancient tradition of building high-altitude sanctuaries and sacred precincts.[8][9][10] Temples were situated on or overlooking mountain summits that were believed to be sacred dwellings of the gods and giants, guarded by archaic men and wild beasts.[5][11][9] Under the influence of suzerain powers, Phoenician temples were Hellenized then Romanized while maintaining balance between foreign elements and Semitic architectural archetypes, among which are tower altars, temenoi and cellas with elevated adytons.[12][13] The temple of Bziza adheres to this model, which characterized Romanized Phoenician temples.[14]

Decline

A policy of repression and persecution of paganism was initiated during the reign of Constantine I when he ordered the pillaging and destruction of Roman temples.[15][16] Constantine's son Constantius II issued a series of decrees that enforced the formal persecution of pagans;[17] he ordered the closing of all pagan temples and forbade pagan sacrifices under pain of death.[18] Under his reign ordinary Christians began to vandalise pagan temples, tombs and monuments.[19][20][21]

The temple of Bziza was converted into a church during the early Byzantine period between the fifth and sixth century[22][23] and underwent further structural modifications during the Middle Ages between the twelfth and the thirteenth century.[23][24] It is colloquially known as the Church of Our Lady of the Pillars (Arabic: كنيسة سيدة العواميد).[25][26]

Modern history

In 1838, French orientalist painters Antoine-Alphonse Montfort and François Lehoux (fr) visited and painted the temple ruins.[27] In 1860, French Semitic languages and civilizations expert Ernest Renan visited the temple; he explained that the Toponymy of Bziza as a corruption of the Phoenician Beth (or Beit) Azizo and attributed the town's temple to Azizos.[28][29][b] Flemish Jesuit orientalist Henri Lammens, who taught at Beirut's Saint Joseph University at the time, also visited the site in 1894 and took a photograph of the temple ruins.[30] Nineteenth-century paintings and early twentieth-century photographs show the removed chapel remains and the oak tree that took root inside of the temple.[31]

In the early twentieth century, German architectural historian Daniel Krencker conducted a survey of the site, later publishing his findings with the assistance of archaeologist Willy Zschietzschmann (de) in the book Römische Tempel in Syrien ("Roman Temples in Syria").[32] According to Krencker the chapel had been in ruins for a long time and a Christian devotion was still maintained in the nineteenth century in the "niche near the door".[23]

In 1965, the site was further excavated by Lebanese-Armenian archaeologist Haroutune Kalayan,[33][34] uncovering the podium and an architectural plan of half of the front pediment etched on one of the temple walls.[35] In the 1990s, the Lebanese Directorate General of Antiquities cleared away parts of the chapel during restoration works to highlight the remains of the ancient temple; only the apses and a rectangular masonry pillar from the Christian chapel remain.[31]

The temple ruins of Bziza were featured on the 35 Lebanese piasters postage stamp in 1971, and on the 200 Lebanese piasters postage stamp in 1985. It appeared again on a 2002 Lebanese postage stamp.[36]

Azizos

Azizos (Palmyrene: 𐡰𐡦𐡩𐡦 ʿzyz)[37] was the Arab god of the morning star;[38][39][40] German biblical scholar Paul de Lagarde showed that Lucifer was one of the god's appellations.[41] In a Dacian inscription, Azizos is given the title Deus bonus puer Phosphorus [the good young god Phosphorus].[42][43] He is portrayed in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra as a horseman, accompanied by his cameleer twin brother Arsu (also called Monimos in later writings).[37] Arsu is believed by Teixidor to be a personification of the evening star.[37] Both gods were regarded as the protectors of traders.[44] In Emperor Julian's work "Hymn to King Helios", Azizos is depicted as the counterpart of the Greek god of war Ares, and Monimos was equated with Hermes, the god of trade and travelers.[45][46] According to the Julian, the cult of Azizos and Monimos was associated with that of Helios in the ancient city of Emesus; he also recounts that Azizos precedes Helios in sacred processions.[45]

Evidence that Aziz, and more frequently Azizu, was used as a common and royal given name is abundant in Palmyrene and Emesan inscriptions.[47][48] Another Latinized form, Azizus, was found in Roman military parchments and papyri.[49] In the Semitic language, the root ʿzyz means "mighty" or "powerful".[48] The female counterpart of ʿAziz is the goddess ʿOzzā, who was worshiped by Semites and was one of the three chief goddesses of the pre-Islamic Arabian religion.[43][42]

Location

The town of Bziza[c] falls in the Koura district within the administrative division of Lebanon's North Governorate, 83 kilometres (52 mi) north of Beirut. The towns sits at an average altitude of 410 metres (1,350 ft), at the southern tip of the Koura (Amioun) plain.[25][50] The temple is located 350 metres (1,150 ft) to the south of the town center,[d] at an elevation of 450 metres (1,480 ft) above sea level.[51] The temple occupies a central position within a region scattered with Roman-era sanctuaries, several of which survive in varying degrees of preservation in neighboring villages.[52] Among them are the temple remains of Amioun to the north of Bziza, the large Roman temple complex of Qasr Naous in Ain Aakrine, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the northeast of Bziza,[53][54][55] and the Temple of Mercury at Hardine, which stands on a mountaintop at an elevation of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft).[55] Further south, beyond the Nahr el-Joz river, the chain of temples surrounding Bziza continues with those of Bcheale, situated at approximately 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) above sea level, and of Assia, at about 900 metres (3,000 ft).[55]

Would you like me to insert this seamlessly into the full passage (so you can see how it reads as one cohesive section)?

Architecture and description

The Bziza temple is a well-preserved tetrastyle prostyle with Ionic order detailing.[56] The ashlar rectangular temple measures 8.5 metres (28 ft) by 14 metres (46 ft).[57][58][59] The pronaos is oriented to the northwest and measures 6.55 metres (21.5 ft) by 2.9 metres (9.5 ft);[34][60] it is fronted by unfluted columns standing on bases carved in the Attic style.[34] The columns measure 5.93 metres (19.5 ft) tall and 0.67 metres (2.2 ft) in diameter.[61] Three of the temple's monolithic pronaos columns still stand, the fourth, found on the temple's northern corner was broken in two parts and was re-erected during restoration works.[34] The columns are crowned with Ionic capitals supporting a frieze that extends over three of the four columns.[34][62] The space between the central columns is wider than that between the distal columns.[63] The colonnade was added at a later stage of the temple's construction as indicated by the style of the ionic capitals that adheres to the model found in Syria and Anatolia as of the second century AD.[34][64] The pronaos is well preserved, it is framed by short antae ending with angular pilasters that are repeated at the rear of the building.[34] The temple was accessible from a stairway that was dismantled.[34]

The pronaos is connected to the cella by two entrances: a massive, richly decorated central door and a smaller side door located to the left of the main entrance.[34][63] The jambs of the main door are adorned with fasciae. The decoration of the lintel and the entablature is finely realized with three fasciae adorned with a rich vegetal decoration. The cornice features modillions bearing images of two diagonally aligned small Victories on either angle of the cornice. The large door's dripstones are in the Corinthian order. The temple's smaller door has only two fasciae. The lintel is decorated with a frieze and a Corinthian dripstone.[34]

The cella consists of two chambers, the first of which is roughly square followed by an adyton to the back of the building.[14] On either side of the temple's cella walls are niches once used to house statues.[22] The two niches of the right cella wall remain. The first niche is surmounted by the form of a scallop; the other one is plain and rectangular.[14] Small columns stood in front of the niches; these supported a simple architrave and an archivolt with three fasciae.[14] Traces of the adyton's platform are visible at the back of the temple. The adyton is recognizable by the remains of two pilasters with Attic style bases in the southwestern wall. The bases of the pilasters are situated 1.66 metres (5.4 ft) above the cella's ground level suggesting that they were part of the temple's edicule, once housing a statue of the temple's deity.[14][65]

Kalayan noted that the exterior of the southwest cella wall bears marks of an architectural sketch for the assembly of the temple's pronaos half-pediment.[35][66][67] Another engraved sketch shows the plan of the temple's entablature.[68] The now lost pediment measured 8.5 metres (28 ft) by 3 metres (9.8 ft).[69] Excavations undertaken by Kalayan revealed an elevated podium that was not noted in Krencker's survey.[34] The uncompleted podium spans the southwestern side of the temple and is structurally independent from the temple's foundation.[34][70] This addition indicates an unfinished plan to transform the prostyle temple into a peripteros.[70]

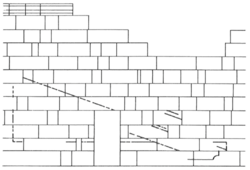

In Byzantine times a church was built within the temple walls.[22][26] The building's orientation was changed from the northwest to the east; the main door of the temple was walled, and a new doorway was opened in the southwest wall of the cella. The adyton's platform and back wall were dismantled and the northeast wall was replaced by a double apse.[22][71] The apses have a four-sided polygonal chevet and are horseshoe-shaped with an aperture of 3.2 metres (10 ft) for the north apse and 3.57 metres (11.7 ft) for the south apse.[72] A whole section of the latter is preserved up to the apse transom, located at 3.3 metres (11 ft) from the current floor of the cella.[72] A molding separates the apse wall from the semi-dome above. The quality of the stereotomy of the apses is comparable to that of the ancient reused temple blocks; the apses date, according to Krencker and Zschietzschmann, to the early Byzantine period.[23][24]

Further modifications were made to the church in the Middle Ages. A 4.33-metre (14.2 ft) rectangular masonry pillar was added to the adjoining wall of the two apses. There were three other similar pillars in the north, west and south corners of the cella that were removed during the 1990s restoration of the temple. The pillars supported groin vaults covering the two naves of the medieval chapel.[23][24] Two 1838 paintings of the facade of the temple depict a gate arranged in the central intercolumnation of the pronaos. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only the left-hand side of the gate remained as demonstrated by a photograph taken during that period.[73] Lebanese-Armenian archaeologist Levon Nordiguian suggests that the pronaos could have served as a church narthex or may have been reserved exclusively for women worshipers through this separate access door.[24]

As well as architectural alterations, several Christian cross engravings were found in the temple. The cross variants provide information on different stages of the site's Christianization. A Latin cross and several bifid crosses similar to the East Syriac variant were found in the temple. Some of the bifid crosses are enclosed in circles.[74] Subterranean rock-carved tombs were found to the south of the temple.[62]

Function

The origin of the modern word temple is the Latin templum. The word templum, however, designates the sacred precinct within which the aedes (shrine or temple) was built. The aedes' main function was to house the cult image of the divinity, which was typically placed in the adyton of the Roman temples in Lebanon.[75][76] The adyton is the innermost chamber of the temple, located at the back of the cella.[14][75] The temple of Bziza is an aedes that follows this arrangement; its elevated adyton was reached through a flight of steps.[14] Roman worship was not conducted within the aedes itself as the building did not have a congregational function like the places of worship of modern monotheistic religions; the aedes was only accessible to priests, augurs, and privileged individuals. Roman religious rituals and sacrifices were conducted on an altar, consecrated to the temple's deity, that was always located outside at the front of the aedes where worshipers gathered. This arrangement reflects the public nature of Roman religious offices, contrasting with the private character of modern religious services.[75][77] In the temple yard, worshipers would face the aedes' doorway, within sight of the deity's image.[78]

In his treatise on architecture, the Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio pronounced a rule for the alignment of temples:

The quarter toward which temples of the immortal gods ought to face is to be determined on the principle that, if there is no reason to hinder and the choice is free, the temple and the statue placed in the cella should face the western quarter of the sky. This will enable those who approach the altar with offerings or sacrifices to face the direction of the sunrise in facing the statue in the temple, and thus those who are undertaking vows look toward the quarter from which the sun comes forth, and likewise the statues themselves appear to be coming forth out of the east to look upon them as they pray and sacrifice.—Vitruvius, De Architectura Libri Decem, IV:v:1

The temple of Bziza is one of the few Roman temples in Lebanon to adhere to this rule as the temple is oriented to the northwest; in Bziza, the cult image was lit by the setting sun through the temple entrance.[79]

See also

- List of Ancient Roman temples

- Temple of Eshmun

- Phoenician Sanctuary of Kharayeb

Notes

- ^a Phoenican cities that became Roman colonies: Beirut (colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus), Baalbek (colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Heliopolis), Acre (colonia Claudia Stabilis Germanica Ptolemais Felix), Tyre (colonia Septimia Tyrus), Sidon (colonia Aurelia Pia metropolis Sidoniorum), Arqa (colonia Caesarea ad Libanum).[80]

- ^b Renan explained in his report: Dans le Liban, le B initial (Bteda, Bteddin, Bhadidat, etc.) est en général une abréviation pour Beth. De même, dans la Gémare, "בי" pour "בית". [In Lebanon, the initial B (Bteda, Bteddin, Bhadidat, etc.) is generally an abbreviation of Beth. Likewise, in the Gemara, "בי" for "בית".] In a later chapter he affirmed his previous interpretation: Le B initial est sans doute le reste de Beth, conservé dans Bziza= Beth-Aziz, Beschtoudar= Beth-Aschtar, Derbaschtar= Deir Beth-Aschtar. [The initial B is without a doubt a corruption of Beth which was preserved in [the town names of] Bziza = Beth-Aziz, Beschtoudar = Beth-Aschtar, Berbaschtar = Deir Beth-Aschtar.] (Renan 1864). This toponymy and temple attribution was upheld by later historians and Onomastolgy experts.[81][82][83][84]

- ^c Bziza is pronounced Bzizo in the mountain villages of North Lebanon due to the survival of the Canaanite shift of the vowel (ā) to (ō).[85][86]

- ^d Viz. coordinates.

References

- ↑ Aliquot 2019, p. 112.

- ↑ Etheredge 2011, p. 130.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Aliquot 2019, p. 117.

- ↑ Lucian 1913, verses 9–10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Aliquot 2019, p. 120.

- ↑ Aliquot 2019, pp. 113–115.

- ↑ Sommer 2013, p. 70.

- ↑ Aliquot 2019, p. 121.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Salles 1995, p. 571.

- ↑ "2 Kings 16:3–4". https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=2+Kings+16%3A3&version=NIV.

- ↑ Ball 2002, p. 322.

- ↑ Aliquot 2019, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Ball 2002, p. 334.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Aliquot 2012, p. 51.

- ↑ Hughes 1947, p. 173.

- ↑ Eusebius 2018, Book 3, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Kirsch 2005, chapter "Let the curiosity of to know the future be silenced forever".

- ↑ Hughes 1947, p. 172.

- ↑ Sozomen 1855, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Theodosius II 438, 9.17.2.

- ↑ Theodosius II 438, 16.10.3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Lendering, Jona (November 23, 2018). "Bziza". Livius. https://www.livius.org/articles/place/bziza/.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Krencker & Zschietzschmann 1978, p. 5.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Nordiguian 2016, p. 396.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Renan 1864, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Abu-Izzeddin 1963, p. 24.

- ↑ Dussaud 1921, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Renan 1864, pp. 134, 238.

- ↑ Hourani 1997.

- ↑ Knuts 2008, p. 413.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Nordiguian 2016, p. 395.

- ↑ Krencker & Zschietzschmann 1978, pp. 3–7.

- ↑ Kalayan 1965.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 34.11 Aliquot 2012, p. 50.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Kalayan 1971, p. 269.

- ↑ "Lebanese postage stamps featuring the temple of Bziza". Colnect.com. Colnect. September 18, 2019. Archived from the original [1],[2],[3] on September 18, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Teixidor 1979, pp. 68–71.

- ↑ Jordan 2014, p. 40.

- ↑ Drijvers 1972, p. 359.

- ↑ Patrich 1990, p. 113.

- ↑ de Lagarde 1889, p. 16.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Drijvers 1972, p. 370.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Smith & Goldziher 1903, p. 302.

- ↑ Jordan 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Julian 362, verse 150.

- ↑ Zellmann-Rohrer 2017, pp. 349–362.

- ↑ Bowen 1869, p. 46.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Dirven 1999, p. 237.

- ↑ Fink 1931, p. 462.

- ↑ "Bziza – Localiban". Localiban. July 2, 2015. https://www.localiban.org/bziza-3868.

- ↑ Kahwagi-Janho 2020, p. 251.

- ↑ Kahwagi-Janho 2020, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ "Ain Aakrine – Localiban". Localiban. July 25, 2015. http://www.localiban.org/ain-aakrine-3856.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona (September 4, 2019). "Ain Akrine (Qasr Naous) – Livius". Livius. https://www.livius.org/articles/place/ain-akrine-qasr-naous/.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Kahwagi-Janho 2020, p. 252.

- ↑ Winter & Fedak 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Dentzer-Feydy 1999, pp. 530–531.

- ↑ Wright 2009, p. xlvii.

- ↑ De Blois, Funke & Hahn 2004, p. 134.

- ↑ Kahwagi-Janho 2020, p. 253.

- ↑ Kahwagi-Janho 2016, p. 192.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Skeels & Skeels 2001, p. 239.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Sommer 2013, p. 71.

- ↑ Kalayan 1971, p. 271.

- ↑ Nordiguian 2016, p. 391.

- ↑ Inglese 1999, p. 2.

- ↑ Pomey 2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Corso 2016, pp. 43, 75–76.

- ↑ Capelle 2017, p. 796.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Nordiguian 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Aliquot 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Nordiguian 2016, p. 394.

- ↑ Nordiguian 2016, pp. 395–396.

- ↑ Garreau Forrest 2011, pp. 193–214.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Aldrete 2004, p. 150.

- ↑ Yasmine 2009, p. 129.

- ↑ Taylor 1971, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Taylor 1971, p. 14.

- ↑ Taylor 1971, p. 12.

- ↑ Aliquot 2019, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ ʿAbboudi 1988, p. 226.

- ↑ Dibs 1902, p. 224.

- ↑ Garreau Forrest 2011, p. 197.

- ↑ Iskandar 2001, p. 143.

- ↑ Cross 1980, p. 14.

- ↑ Feghali 1918, p. 21.

Bibliography

- ʿAbboudi, Henriette Saʿid (1988) (in ar). معجم الحضارات السامية. Tripoli, Lebanon: Jarrous press. pp. 225–226. OCLC 949513113. https://archive.org/details/54654_20170409.

- Abu-Izzeddin, Halim Said (1963) (in en). Lebanon and Its Provinces: a Study by the Governors of the Five Provinces. Beirut: Khayats. https://books.google.com/books?id=O1dtAAAAMAAJ&q=bziza+temple.

- Aldrete, Gregory S. (2004) (in en). Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii and Ostia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-03-13331-74-9. https://archive.org/details/dailylifeinroman00aldr.

- Aliquot, Julien (2012). "Liban-Nord" (in fr). La Vie religieuse au Liban sous l'Empire Romain. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. Beirut: Presses de l’IFPO. pp. 233–271. ISBN 978-23-51591-60-4. http://books.openedition.org/ifpo/1451. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Aliquot, Julien (2019). "Chapter 9: Phoenicia in the Roman Empire". in Lopez-Ruiz, Carolina (in en). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 111–124. ISBN 978-01-90058-38-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=SBOlDwAAQBAJ.

- Ball, Warwick (2002) (in en). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-11-34823-87-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=qQKIAgAAQBAJ.

- Bowen, Francis (1869) (in en). Key to the Acts of the Apostles; or, The Acts of the Apostles historically, chronologically and geographically considered. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 1202852243. https://books.google.com/books?id=V78CAAAAQAAJ.

- Capelle, Jeanne (2017). "Les épures du théâtre de Milet : pratiques de chantiers antiques" (in fr). Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (Athens) 141 (2): 769–820. doi:10.4000/bch.583. ISSN 0007-4217. https://journals.openedition.org/bch/583.

- Corso, Antonio (2016). Drawings in Greek and Roman Architecture. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 978-17-84913-71-7.

- Cross, Frank Moore (April 1, 1980). "Newly Found Inscriptions in Old Canaanite and Early Phoenician Scripts". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 238 (238): 1–20. doi:10.2307/1356511. ISSN 0003-097X.

- De Blois, Lukas; Funke, Peter; Hahn, Johannes, eds (June 30 – July 4, 2004). "The Impact of Imperial Rome on Religions, Ritual and Religious Life in the Roman Empire". Fifth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476). 5. Münster: Brill (published September 1, 2006). ISBN 978-90-47411-34-5. https://brill.com/view/title/13342. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- Dentzer-Feydy, Jacqueline (1999). "Les temples de l'Hermon, de la Bekaa et de la vallée du Barada dessinés par W. J. Bankes (1786–1855)" (in fr). Topoi. Orient-Occident (Lyon) 9 (2): 527–568. doi:10.3406/topoi.1999.1850.

- Dibs, Yūsuf (1902) (in ar). كتاب تاريخ سورية. 2. Beirut: المكتبة الكاثوليكية – دار المشرق. https://books.google.com/books?id=o-BAAQAAMAAJ.

- Dirven, Lucinda (1999) (in en). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04115-89-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=_LfXg2r6FT0C.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1972). "The cult of Azizos and Monimos at Edessa". in Layton, Bentley (in en). Studies in the History of Religions. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Archive. pp. 355–371. https://books.google.com/books?id=1Jg3AAAAIAAJ.

- Dussaud, René (1921). "Le peintre montfort en syrie (1837–1838): III. Le Liban et la Terre Sainte" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut Francais du Proche-Orient) 2 (1): 63–72. doi:10.3406/syria.1921.8763.

- Etheredge, Laura S. (2011). "Chapter 10 – Lebanon past and present" (in en). Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. New York City: Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen group. pp. 117–159. ISBN 978-16-15303-29-8. OCLC 694831100. https://books.google.com/books?id=rLZQrmRQafcC.

- Eusebius, (Eusebius of Caesarea) (2018). Horn, Apostle Arne. ed (in en). The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine. Cayenne, French Guiana: New Apostolic Bible Covenant. ISBN 978-02-44723-99-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=SmVyDwAAQBAJ.

- Feghali, Michel T. (1918) (in fr). Étude sur les emprunts syriaques dans les parlers arabes du Liban. Paris: Editions Honoré Champion. doi:10.7282/T3M0474W. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/45837/.

- Fink, Robert Orwill (1931). Roman Military Records on Papyrus. California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780829501742. https://books.google.com/books?id=oXb1DB8DegMC.

- Garreau Forrest, Sophie (January 1, 2011). "Réhabilitation et réaménagements des sanctuaires païens dans les provinces maritime et Libanaise de la Phénicie à l'époque protobyzantine (IVe–VIIIe siècles)". Semitica et Classica (Turnhout) 4: 193–214. doi:10.1484/J.SEC.1.102514. ISSN 2031-5937.

- Hourani, Guita (1997). "Frescoes of Saint Theodore's". The Journal of Maronite Studies (Washington D.C.: Maronite research institute). http://www.maronite-institute.org/MARI/JMS/april97/Frescoes_of_Saint_Theodores.htm. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- Hughes, Philip (1947) (in en). A History of the Church: The church and the world in which the church was founded. 2d ed. 1949. v. 2. The church and the world the church created. 2d ed. 1949. v. 3. The revolt against the church. pt. 1: Aquinas to Luther. 1947. London: Sheed & Ward. OCLC 226658807. https://books.google.com/books?id=-jEcAAAAMAAJ.

- Inglese, Carlo (1999) (in it). Tracciati di cantiere incisi nel Mausoleo di Augusto e sul Pantheon a Roma: ipotesi di lettura. Rome: Gangemi. ISBN 978-88-74489-08-4. http://research.arc.uniroma1.it:80/xmlui/handle/123456789/496.

- Iskandar, Amine Jules (2001) (in fr). La dimension Syriaque dans l'art et l'architecture au Liban. Kaslik, Lebanon: Cedlusek. pp. 143. OCLC 49912363. https://books.google.com/books?id=1sWfAAAAMAAJ.

- Jordan, Michael (2014). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-09-65510-25-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=aqDC5bwx4_wC&pg=PA30.

- Julian, (Flavius Claudius Iulianus) (362). "Oration IV – Hymn to King Helios". Loeb Classical Library – Julian, Volume I. L013: Volume I. Orations 1–5. Harvard: Harvard University Press (published 1913). https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Hymn_to_King_Helios.

- Kahwagi-Janho, Hany (2016). "Le temple caché sous l'église Saint-Charbel de Maad. Une tentative pour retracer le plan du temple antique sous-jacent" (in fr). Chronos (Beirut) 34. https://www.academia.edu/28767193.

- Kahwagi-Janho, Hany (2020). "Le Temple Ionique De Bziza: Architecture Et Transformations". Syria 97: 249–304. ISSN 0039-7946. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27282892.

- Kalayan, Haroutune (1965) (in fr). Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth. 18–19. Beirut: Musée National Libanais. https://books.google.com/books?id=B6YqAAAAMAAJ.

- Kalayan, Haroutune (1971). "Notes on Assembly Marks, Drawings and Models Concerning the Roman Period Monuments in Lebanon" (in en). Syria (Damascus: Direction générale des antiquités et des musées, République Arabe Syrienne) 21. OCLC 941036518. https://books.google.com/books?id=F9aVDAEACAAJ.

- Kirsch, Jonathan (2005) (in en). God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism. London: Penguin compass. ISBN 978-14-40626-58-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=WXNn5Q3C58EC.

- Knuts, Stijen (2008). "Henri Lammens (1862–1937) en de studie van de Islam en het Arabisch". Trajecta (Amsterdam) 17. ISSN 0778-8304. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265059566.

- Krencker, Daniel; Zschietzschmann, Willy (1978) (in de). Römische Tempel in Syrien. Berlin: W. de Gruyter. ISBN 978-31-10049-89-3. OCLC 1072776246. https://books.google.com/books?id=DR1IAQAAIAAJ.

- de Lagarde, Paul (1889) (in de). Uebersicht über die im Aramäischen, Arabischen und Hebräischen übliche Bildung der Nomina. Göttingen: Dieterich. OCLC 8528397. https://books.google.com/books?id=ucEDAAAAMAAJ.

- Lucian, (Lucian of Samosata) (1913). Garstang, John. ed. De dea Syria. Robarts – University of Toronto. London: London Constable. OCLC 938998722. https://archive.org/details/syriangoddessbei00luciuoft.

- Nordiguian, Lévon (2005) (in fr). Temples de l'époque romaine au Liban. Beirut: PUSJ, Presses de l'Université Saint-Joseph. ISBN 978-99-53455-62-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=FHotAQAAIAAJ.

- Nordiguian, Lévon (2016). "Trois chapelles médiévales de Bziza" (in fr). Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut) 65. https://www.academia.edu/39951632.

- Patrich, J. (1990). The Formation of Nabataean Art: Prohibition of a Graven Image Among the Nabataeans. Ancient Near East. Leiden: Magnes Press. ISBN 978-90-04-09285-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=8cMUAAAAIAAJ.

- Pomey, Patrice (2009). Nowacki, Horst. ed (in en). Creating Shapes in Civil and Naval Architecture: A Cross-Disciplinary Comparison. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04173-45-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=GxiwCQAAQBAJ.

- Renan, Ernest (1864) (in fr). Mission de Phénicie dirigée par Ernest Renan : Texte. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. OCLC 490085044. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5529563s.

- Salles, Jean-Francois (1995). Krings, Véronique. ed (in fr). Handbuch der Orientalistik: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10068-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=tdPwhNHB3Z4C.

- Skeels, Frank; Skeels, Laure (2001) (in fr). Le Liban connu et méconnu: guide détaillé. Beirut: GEO Projects. ISBN 978-18-59641-65-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=rM9FAQAAIAAJ.

- Smith, William Robertson; Goldziher, Ignác (1903) (in en). Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia. London: Adam and Charles Black. OCLC 2135752. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z12fpjj53hwC.

- Sommer, Michael (2013). "Creating civic space through religious innovation? The case of post-Seleucid Beqaa Valley". in Kaizer, Ted. Cities and Gods – Religious Space in Transition. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-90-42929-05-0. https://uol.de/fileadmin/user_upload/geschichte/alte_geschichte/Sommer_2013_Civic_space.pdf.

- Sozomen, (Salminius Hermias Sozomenus) (1855) (in en). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen, Comprising a History of the Church, from A.D. 324 to A.D. 440: Tr. from the Greek: with a Memoir of the Author. Also: The Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, as Epitomised by Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 931119707. https://books.google.com/books?id=aZrYAAAAMAAJ.

- Taylor, George (1971) (in fr). Les Temples Romains au Liban. Beirut: Dar el-Machreq Publishers. OCLC 365828. https://books.google.com/books?id=ii8NAQAAIAAJ.

- Teixidor, Javier (1979) (in en). The Pantheon of Palmyra. Leiden: Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04059-87-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=TccUAAAAIAAJ.

- Theodosius II (438). "Codex Theodosianus" (in la). http://ancientrome.ru/ius/library/codex/theod/tituli.htm.

- Winter, Frederick E.; Fedak, Janos (2006) (in en). Studies in Hellenistic Architecture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-08-02039-14-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=03UNLhtEP1oC.

- Wright, G. R. H. (2009) (in en). Ancient Building Technology, Volume 3: Construction (2 Vols). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04177-45-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=CQHsKG6g5zwC.

- Yasmine, Jean (2009). "Transformations monumentales de sanctuaires et de temples antiques. Les cas de Niha et Hardine". Topoi. Orient-Occident 16 (1): 121–152. doi:10.3406/topoi.2009.2297.

- Zellmann-Rohrer, Michael (December 15, 2017). "Jean-Baptiste Yon & Julien Aliquot, Inscriptions grecques et latines du Musée national de Beyrouth" (in fr). Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire (Beirut) (94): 349–362. doi:10.4000/syria.5621. ISSN 0039-7946. http://journals.openedition.org/syria/5621.

External links

Template:Roman Archaeological sites in Beirut & Lebanon

|