Scoring rule

In decision theory, a scoring rule[1] provides a summary measure for the evaluation of probabilistic predictions or forecasts. It is applicable to tasks in which predictions assign probabilities to events, i.e. one issues a probability distribution as prediction. This includes probabilistic classification of a set of mutually exclusive outcomes or classes.

On the other hand, a scoring function[2] provides a summary measure for the evaluation of point predictions, i.e. one predicts a property or functional , like the expectation or the median.

Scoring rules and scoring functions can be thought of as "cost function" or "loss function". They are evaluated as empirical mean of a given sample, simply called score. Scores of different predictions or models can then be compared to conclude which model is best.

If a cost is levied in proportion to a proper scoring rule, the minimal expected cost corresponds to reporting the true set of probabilities. Proper scoring rules are used in meteorology, finance, and pattern classification where a forecaster or algorithm will attempt to minimize the average score to yield refined, calibrated probabilities (i.e. accurate probabilities).

Motivation

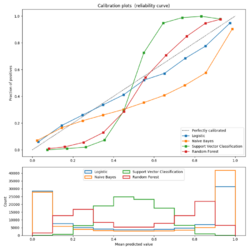

Since the metrics in Evaluation of binary classifiers are not evaluating the calibration, scoring rules which can do so are needed. These scoring rules can be used as loss functions in empirical risk minimization.

Definition

Consider a sample space , a σ-algebra of subsets of and a convex class of probability measures on . A function defined on and taking values in the extended real line, , is -quasi-integrable if it is measurable with respect to and is quasi-integrable with respect to all .

Probabilistic forecast

A probabilistic forecast is any probability measure .

Scoring rule

A scoring rule is any extended real-valued function such that is -quasi-integrable for all . represents the loss or penalty when the forecast is issued and the observation materializes.

Point forecast

A point forecast is a functional, i.e. a potentially set-valued mapping .

Scoring function

A scoring function is any real-valued function where represents the loss or penalty when the point forecast is issued and the observation materializes.

Orientation

Scoring rules and scoring functions are negatively (positively) oriented if smaller (larger) values mean better. Here we adhere to negative orientation, hence the association with "loss".

Expected Score

We write for the expected score under

Sample average score

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Needs attention from expert. Are the sample averages correct here? (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Given random samples and corresponding forecasts or (e.g. forecasts from a single model), one calculates the (importance sample) estimated expected score as

or

Average scores are used to compare and rank different forecast(er)s or models.

Propriety and consistency

Strictly proper scoring rules and strictly consistent scoring functions encourage honest forecasts by maximization of the expected reward: If a forecaster is given a reward of if realizes (e.g. ), then the highest expected reward (lowest score) is obtained by reporting the true probability distribution.[1]

Proper scoring rules

We write for the expected score under

A scoring rule is proper relative to if (assuming negative orientation)

- for all .

It is strictly proper if the above equation holds with equality if and only if .

Consistent scoring functions

A scoring function is consistent for the functional relative to the class if

- for all , all and all .

It is strictly consistent if it is consistent and equality in the above equation implies that .

Example application of scoring rules

An example of probabilistic forecasting is in meteorology where a weather forecaster may give the probability of rain on the next day. One could note the number of times that a 25% probability was quoted, over a long period, and compare this with the actual proportion of times that rain fell. If the actual percentage was substantially different from the stated probability we say that the forecaster is poorly calibrated. A poorly calibrated forecaster might be encouraged to do better by a bonus system. A bonus system designed around a proper scoring rule will incentivize the forecaster to report probabilities equal to his personal beliefs.[3]

In addition to the simple case of a binary decision, such as assigning probabilities to 'rain' or 'no rain', scoring rules may be used for multiple classes, such as 'rain', 'snow', or 'clear', or continuous responses like the amount of rain per day.

The image to the right shows an example of a scoring rule, the logarithmic scoring rule, as a function of the probability reported for the event that actually occurred. One way to use this rule would be as a cost based on the probability that a forecaster or algorithm assigns, then checking to see which event actually occurs.

Examples of proper scoring rules

There are an infinite number of scoring rules, including entire parameterized families of strictly proper scoring rules. The ones shown below are simply popular examples.

Categorical variables

For a categorical response variable with mutually exclusive events, , a probabilistic forecaster or algorithm will return a probability vector with a probability for each of the outcomes.

Logarithmic score

The logarithmic scoring rule is a local strictly proper scoring rule. This is also the negative of surprisal, which is commonly used as a scoring criterion in Bayesian inference; the goal is to minimize expected surprise. This scoring rule has strong foundations in information theory.

Here, the score is calculated as the logarithm of the probability estimate for the actual outcome. That is, a prediction of 80% that correctly proved true would receive a score of ln(0.8) = −0.22. This same prediction also assigns 20% likelihood to the opposite case, and so if the prediction proves false, it would receive a score based on the 20%: ln(0.2) = −1.6. The goal of a forecaster is to maximize the score and for the score to be as large as possible, and −0.22 is indeed larger than −1.6.

If one treats the truth or falsity of the prediction as a variable x with value 1 or 0 respectively, and the expressed probability as p, then one can write the logarithmic scoring rule as x ln(p) + (1 − x) ln(1 − p). Note that any logarithmic base may be used, since strictly proper scoring rules remain strictly proper under linear transformation. That is:

is strictly proper for all .

Brier/Quadratic score

The quadratic scoring rule is a strictly proper scoring rule

where is the probability assigned to the correct answer and is the number of classes.

The Brier score, originally proposed by Glenn W. Brier in 1950,[4] can be obtained by an affine transform from the quadratic scoring rule.

Where when the th event is correct and otherwise and is the number of classes.

An important difference between these two rules is that a forecaster should strive to maximize the quadratic score yet minimize the Brier score . This is due to a negative sign in the linear transformation between them.

Hyvärinen scoring rule

The Hyvärinen scoring function (of a density p) is defined by[5]

Where denotes the Hessian trace and denotes the gradient. This scoring rule can be used to computationally simplify parameter inference and address Bayesian model comparison with arbitrarily-vague priors.[5][6] It was also used to introduce new information-theoretic quantities beyond the existing information theory.[7]

Spherical score

The spherical scoring rule is also a strictly proper scoring rule

Continuous variables

Continuous ranked probability score

The continuous ranked probability score (CRPS)[8] is a strictly proper scoring rule much used in Meteorology. It is defined as

where is the forecast cumulative distribution function, is the Heaviside step function and is the observation. Note that the forecast estimates multiple probabilities, so that a cumulative distribution function arises.

Interpretation of proper scoring rules

All proper scoring rules are equal to weighted sums (integral with a non-negative weighting functional) of the losses in a set of simple two-alternative decision problems that use the probabilistic prediction, each such decision problem having a particular combination of associated cost parameters for false positive and false negative decisions. A strictly proper scoring rule corresponds to having a nonzero weighting for all possible decision thresholds. Any given proper scoring rule is equal to the expected losses with respect to a particular probability distribution over the decision thresholds; thus the choice of a scoring rule corresponds to an assumption about the probability distribution of decision problems for which the predicted probabilities will ultimately be employed, with for example the quadratic loss (or Brier) scoring rule corresponding to a uniform probability of the decision threshold being anywhere between zero and one. The classification accuracy score (percent classified correctly), a single-threshold scoring rule which is zero or one depending on whether the predicted probability is on the appropriate side of 0.5, is a proper scoring rule but not a strictly proper scoring rule because it is optimized (in expectation) not only by predicting the true probability but by predicting any probability on the same side of 0.5 as the true probability.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

Comparison of strictly proper scoring rules

Shown below on the left is a graphical comparison of the Logarithmic, Quadratic, and Spherical scoring rules for a binary classification problem. The x-axis indicates the reported probability for the event that actually occurred.

It is important to note that each of the scores have different magnitudes and locations. The magnitude differences are not relevant however as scores remain proper under affine transformation. Therefore, to compare different scores it is necessary to move them to a common scale. A reasonable choice of normalization is shown at the picture on the right where all scores intersect the points (0.5,0) and (1,1). This ensures that they yield 0 for a uniform distribution (two probabilities of 0.5 each), reflecting no cost or reward for reporting what is often the baseline distribution. All normalized scores below also yield 1 when the true class is assigned a probability of 1.

Characteristics

Affine transformation

A strictly proper scoring rule, whether binary or multiclass, after an affine transformation remains a strictly proper scoring rule.[3] That is, if is a strictly proper scoring rule then with is also a strictly proper scoring rule, though if then the optimization sense of the scoring rule switches between maximization and minimization.

Locality

A proper scoring rule is said to be local if its estimate for the probability of a specific event depends only on the probability of that event. This statement is vague in most descriptions but we can, in most cases, think of this as the optimal solution of the scoring problem "at a specific event" is invariant to all changes in the observation distribution that leave the probability of that event unchanged. All binary scores are local because the probability assigned to the event that did not occur is determined so there is no degree of flexibility to vary over.

Affine functions of the logarithmic scoring rule are the only strictly proper local scoring rules on a finite set that is not binary.

Decomposition

The expectation value of a proper scoring rule can be decomposed into the sum of three components, called uncertainty, reliability, and resolution,[15][16] which characterize different attributes of probabilistic forecasts:

If a score is proper and negatively oriented (such as the Brier Score), all three terms are positive definite. The uncertainty component is equal to the expected score of the forecast which constantly predicts the average event frequency. The reliability component penalizes poorly calibrated forecasts, in which the predicted probabilities do not coincide with the event frequencies.

The equations for the individual components depend on the particular scoring rule. For the Brier Score, they are given by

where is the average probability of occurrence of the binary event , and is the conditional event probability, given , i.e.

Problems

Extreme class imbalance poses a major problem for obtaining good probability estimates.[17]

See also

Literature

- Strictly Proper Scoring Rules, Prediction, and Estimation. Tilmann Gneiting &Adrian E Raftery Pages 359-378, https://doi.org/10.1198/016214506000001437, pdf

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gneiting, Tilmann; Raftery, Adrian E. (2007). "Strictly Proper Scoring Rules, Prediction, and Estimation". Journal of the American Statistical Association 102 (447): 359–378. doi:10.1198/016214506000001437. https://sites.stat.washington.edu/raftery/Research/PDF/Gneiting2007jasa.pdf.

- ↑ Gneiting, Tilmann (2011). "Making and Evaluating Point Forecasts". Journal of the American Statistical Association 106 (494): 746–762. doi:10.1198/jasa.2011.r10138.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bickel, E.J. (2007). "Some Comparisons among Quadratic, Spherical, and Logarithmic Scoring Rules". Decision Analysis 4 (2): 49–65. doi:10.1287/deca.1070.0089. http://faculty.engr.utexas.edu/bickel/Papers/QSL_Comparison.pdf.

- ↑ Brier, G.W. (1950). "Verification of forecasts expressed in terms of probability". Monthly Weather Review 78 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1950)078<0001:VOFEIT>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 1950MWRv...78....1B. http://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/mwr/078/mwr-078-01-0001.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hyvärinen, Aapo (2005). "Estimation of Non-Normalized Statistical Models by Score Matching". Journal of Machine Learning Research 6 (24): 695–709. ISSN 1533-7928. http://jmlr.org/papers/v6/hyvarinen05a.html.

- ↑ Shao, Stephane; Jacob, Pierre E.; Ding, Jie; Tarokh, Vahid (2019-10-02). "Bayesian Model Comparison with the Hyvärinen Score: Computation and Consistency". Journal of the American Statistical Association 114 (528): 1826–1837. doi:10.1080/01621459.2018.1518237. ISSN 0162-1459. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2018.1518237.

- ↑ Ding, Jie; Calderbank, Robert; Tarokh, Vahid (2019). "Gradient Information for Representation and Modeling". Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32: 2396–2405. http://papers.neurips.cc/paper/8510-gradient-information-for-representation-and-modeling.

- ↑ Zamo, Michaël; Naveau, Philippe (2018-02-01). "Estimation of the Continuous Ranked Probability Score with Limited Information and Applications to Ensemble Weather Forecasts" (in en). Mathematical Geosciences 50 (2): 209–234. doi:10.1007/s11004-017-9709-7. ISSN 1874-8953.

- ↑ Leonard J. Savage. Elicitation of personal probabilities and expectations. J. of the American Stat. Assoc., 66(336):783–801, 1971.

- ↑ Schervish, Mark J. (1989). "A General Method for Comparing Probability Assessors", Annals of Statistics 17(4) 1856–1879, https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.aos/1176347398

- ↑ Rosen, David B. (1996). "How good were those probability predictions? The expected recommendation loss (ERL) scoring rule". in Heidbreder, G.. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- ↑ Roulston, M. S., & Smith, L. A. (2002). Evaluating probabilistic forecasts using information theory. Monthly Weather Review, 130, 1653–1660. See APPENDIX "Skill Scores and Cost–Loss". [1]

- ↑ "Loss Functions for Binary Class Probability Estimation and Classification: Structure and Applications", Andreas Buja, Werner Stuetzle, Yi Shen (2005) http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.184.5203

- ↑ Hernandez-Orallo, Jose; Flach, Peter; and Ferri, Cesar (2012). "A Unified View of Performance Metrics: Translating Threshold Choice into Expected Classification Loss." Journal of Machine Learning Research 13 2813–2869. http://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume13/hernandez-orallo12a/hernandez-orallo12a.pdf

- ↑ Murphy, A.H. (1973). "A new vector partition of the probability score". Journal of Applied Meteorology 12 (4): 595–600. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1973)012<0595:ANVPOT>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 1973JApMe..12..595M.

- ↑ Bröcker, J. (2009). "Reliability, sufficiency, and the decomposition of proper scores". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 135 (643): 1512–1519. doi:10.1002/qj.456. Bibcode: 2009QJRMS.135.1512B. http://www.personal.reading.ac.uk/~pt904209/publications/decomposition_qjrms.pdf.

- ↑ Wallace, Byron & Dahabreh, Issa. (2012). Class Probability Estimates are Unreliable for Imbalanced Data (and How to Fix Them). Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, ICDM. 695-704. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2012.115

External links

- Video comparing spherical, quadratic and logarithmic scoring rules

- Local Proper Scoring Rules

- Scoring Rules and Decision Analysis Education

- Strictly Proper Scoring Rules

- Scoring Rules and uncertainty

- Damage Caused by Classification Accuracy and Other Discontinuous Improper Accuracy Scoring Rules

|