Quasicircle

In mathematics, a quasicircle is a Jordan curve in the complex plane that is the image of a circle under a quasiconformal mapping of the plane onto itself. Originally introduced independently by (Pfluger 1961) and (Tienari 1962), in the older literature (in German) they were referred to as quasiconformal curves, a terminology which also applied to arcs.[1][2] In complex analysis and geometric function theory, quasicircles play a fundamental role in the description of the universal Teichmüller space, through quasisymmetric homeomorphisms of the circle. Quasicircles also play an important role in complex dynamical systems.

Definitions

A quasicircle is defined as the image of a circle under a quasiconformal mapping of the extended complex plane. It is called a K-quasicircle if the quasiconformal mapping has dilatation K. The definition of quasicircle generalizes the characterization of a Jordan curve as the image of a circle under a homeomorphism of the plane. In particular a quasicircle is a Jordan curve. The interior of a quasicircle is called a quasidisk.[3]

As shown in (Lehto Virtanen), where the older term "quasiconformal curve" is used, if a Jordan curve is the image of a circle under a quasiconformal map in a neighbourhood of the curve, then it is also the image of a circle under a quasiconformal mapping of the extended plane and thus a quasicircle. The same is true for "quasiconformal arcs" which can be defined as quasiconformal images of a circular arc either in an open set or equivalently in the extended plane.[4]

Geometric characterizations

(Ahlfors 1963) gave a geometric characterization of quasicircles as those Jordan curves for which the absolute value of the cross-ratio of any four points, taken in cyclic order, is bounded below by a positive constant.

Ahlfors also proved that quasicircles can be characterized in terms of a reverse triangle inequality for three points: there should be a constant C such that if two points z1 and z2 are chosen on the curve and z3 lies on the shorter of the resulting arcs, then[5]

This property is also called bounded turning[6] or the arc condition.[7]

For Jordan curves in the extended plane passing through ∞, (Ahlfors 1966) gave a simpler necessary and sufficient condition to be a quasicircle.[8][9] There is a constant C > 0 such that if z1, z2 are any points on the curve and z3 lies on the segment between them, then

These metric characterizations imply that an arc or closed curve is quasiconformal whenever it arises as the image of an interval or the circle under a bi-Lipschitz map f, i.e. satisfying

for positive constants Ci.[10]

Quasicircles and quasisymmetric homeomorphisms

If φ is a quasisymmetric homeomorphism of the circle, then there are conformal maps f of [z| < 1 and g of |z|>1 into disjoint regions such that the complement of the images of f and g is a Jordan curve. The maps f and g extend continuously to the circle |z| = 1 and the sewing equation

holds. The image of the circle is a quasicircle.

Conversely, using the Riemann mapping theorem, the conformal maps f and g uniformizing the outside of a quasicircle give rise to a quasisymmetric homeomorphism through the above equation.

The quotient space of the group of quasisymmetric homeomorphisms by the subgroup of Möbius transformations provides a model of universal Teichmüller space. The above correspondence shows that the space of quasicircles can also be taken as a model.[11]

Quasiconformal reflection

A quasiconformal reflection in a Jordan curve is an orientation-reversing quasiconformal map of period 2 which switches the inside and the outside of the curve fixing points on the curve. Since the map

provides such a reflection for the unit circle, any quasicircle admits a quasiconformal reflection. (Ahlfors 1963) proved that this property characterizes quasicircles.

Ahlfors noted that this result can be applied to uniformly bounded holomorphic univalent functions f(z) on the unit disk D. Let Ω = f(D). As Carathéodory had proved using his theory of prime ends, f extends continuously to the unit circle if and only if ∂Ω is locally connected, i.e. admits a covering by finitely many compact connected sets of arbitrarily small diameter. The extension to the circle is 1-1 if and only if ∂Ω has no cut points, i.e. points which when removed from ∂Ω yield a disconnected set. Carathéodory's theorem shows that a locally set without cut points is just a Jordan curve and that in precisely this case is the extension of f to the closed unit disk a homeomorphism.[12] If f extends to a quasiconformal mapping of the extended complex plane then ∂Ω is by definition a quasicircle. Conversely (Ahlfors 1963) observed that if ∂Ω is a quasicircle and R1 denotes the quasiconformal reflection in ∂Ω then the assignment

for |z| > 1 defines a quasiconformal extension of f to the extended complex plane.

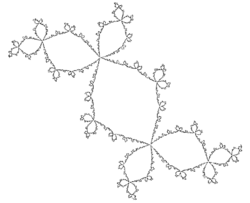

Complex dynamical systems

Quasicircles were known to arise as the Julia sets of rational maps R(z). (Sullivan 1985) proved that if the Fatou set of R has two components and the action of R on the Julia set is "hyperbolic", i.e. there are constants c > 0 and A > 1 such that

on the Julia set, then the Julia set is a quasicircle.[5]

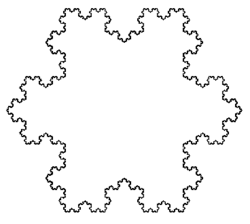

There are many examples:[13][14]

- quadratic polynomials R(z) = z2 + c with an attracting fixed point

- the Douady rabbit (c = –0.122561 + 0.744862i, where c3 + 2 c2 + c + 1 = 0)

- quadratic polynomials z2 + λz with |λ| < 1

- the Koch snowflake

Quasi-Fuchsian groups

Quasi-Fuchsian groups are obtained as quasiconformal deformations of Fuchsian groups. By definition their limit sets are quasicircles.[15][16][17][18][19]

Let Γ be a Fuchsian group of the first kind: a discrete subgroup of the Möbius group preserving the unit circle. acting properly discontinuously on the unit disk D and with limit set the unit circle.

Let μ(z) be a measurable function on D with

such that μ is Γ-invariant, i.e.

for every g in Γ. (μ is thus a "Beltrami differential" on the Riemann surface D / Γ.)

Extend μ to a function on C by setting μ(z) = 0 off D.

admits a solution unique up to composition with a Möbius transformation.

It is a quasiconformal homeomorphism of the extended complex plane.

If g is an element of Γ, then f(g(z)) gives another solution of the Beltrami equation, so that

is a Möbius transformation.

The group α(Γ) is a quasi-Fuchsian group with limit set the quasicircle given by the image of the unit circle under f.

Hausdorff dimension

It is known that there are quasicircles for which no segment has finite length.[21] The Hausdorff dimension of quasicircles was first investigated by (Gehring Väisälä), who proved that it can take all values in the interval [1,2).[22] (Astala 1993), using the new technique of "holomorphic motions" was able to estimate the change in the Hausdorff dimension of any planar set under a quasiconformal map with dilatation K. For quasicircles C, there was a crude estimate for the Hausdorff dimension[23]

where

On the other hand, the Hausdorff dimension for the Julia sets Jc of the iterates of the rational maps

had been estimated as result of the work of Rufus Bowen and David Ruelle, who showed that

Since these are quasicircles corresponding to a dilatation

where

this led (Becker Pommerenke) to show that for k small

Having improved the lower bound following calculations for the Koch snowflake with Steffen Rohde and Oded Schramm, (Astala 1994) conjectured that

This conjecture was proved by (Smirnov 2010); a complete account of his proof, prior to publication, was already given in (Astala Iwaniec).

For a quasi-Fuchsian group (Bowen 1979) and (Sullivan 1982) showed that the Hausdorff dimension d of the limit set is always greater than 1. When d < 2, the quantity

is the lowest eigenvalue of the Laplacian of the corresponding hyperbolic 3-manifold.[24][25]

Notes

- ↑ Lehto & Virtanen 1973

- ↑ Lehto 1983, p. 49.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Lehto 1987, p. 38

- ↑ Lehto & Virtanen 1973, pp. 97–98

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Carleson & Gamelin 1993, p. 102

- ↑ Lehto & Virtanen 1973, pp. 100–102

- ↑ Lehto 1983, p. 45.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Ahlfors 1966, p. 81

- ↑ Lehto 1983, pp. 48–49.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Lehto & Virtanen 1973, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Lehto 1983, p. [page needed].[full citation needed]

- ↑ Pommerenke 1975, pp. 271–281

- ↑ Carleson & Gamelin 1993, pp. 123–126

- ↑ Rohde 1991

- ↑ Bers 1961

- ↑ Bowen 1979

- ↑ Mumford, Series & Wright 2002

- ↑ Imayoshi & Taniguchi 1992, p. 147

- ↑ Marden 2007, pp. 79–80, 134

- ↑ Carleson & Gamelin 1993, p. 122

- ↑ Lehto & Virtanen 1973, p. 104

- ↑ Lehto 1982, p. 38.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Astala, Iwaniec & Martin 2009

- ↑ Astala & Zinsmeister 1994

- ↑ Marden 2007, p. 284

References

- Ahlfors, Lars V. (1966), Lectures on quasiconformal mappings, Van Nostrand

- Ahlfors, L. (1963), "Quasiconformal reflections", Acta Mathematica 109: 291–301, doi:10.1007/bf02391816

- Astala, K. (1993), "Distortion of area and dimension under quasiconformal mappings in the plane", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (24): 11958–11959, doi:10.1073/pnas.90.24.11958, PMID 11607447, Bibcode: 1993PNAS...9011958A

- Astala, K.; Zinsmeister, M. (1994), "Holomorphic families of quasi-Fuchsian groups", Ergodic Theory Dynam. Systems 14 (2): 207–212, doi:10.1017/s0143385700007847

- Astala, K. (1994), "Area distortion of quasiconformal mappings", Acta Math. 173: 37–60, doi:10.1007/bf02392568

- Astala, Kari; Iwaniec, Tadeusz; Martin, Gaven (2009), Elliptic partial differential equations and quasiconformal mappings in the plane, Princeton mathematical series, 48, Princeton University Press, pp. 332–342, ISBN 978-0-691-13777-3, Section 13.2, Dimension of quasicircles.

- Becker, J.; Pommerenke, C. (1987), "On the Hausdorff dimension of quasicircles", Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. Ser. A I Math. 12: 329–333, doi:10.5186/aasfm.1987.1206

- Bers, Lipman (August 1961). "Uniformization by Beltrami equations". Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 14 (3): 215–228. doi:10.1002/cpa.3160140304.

- Bowen, R. (1979), "Hausdorff dimension of quasicircles", Inst. Hautes Études Sci. Publ. Math. 50: 11–25, doi:10.1007/BF02684767, http://www.numdam.org/item/PMIHES_1979__50__11_0/

- Carleson, L.; Gamelin, T. D. W. (1993), Complex dynamics, Universitext: Tracts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97942-7, https://archive.org/details/complexdynamics0000carl

- Gehring, F. W.; Väisälä, J. (1973), "Hausdorff dimension and quasiconformal mappings", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 6 (3): 504–512, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-6.3.504

- Gehring, F. W. (1982), Characteristic properties of quasidisks, Séminaire de Mathématiques Supérieures, 84, Presses de l'Université de Montréal, ISBN 978-2-7606-0601-2

- Imayoshi, Y.; Taniguchi, M. (1992), An Introduction to Teichmüller spaces, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-70088-5 +

- Lehto, O. (1987), Univalent functions and Teichmüller spaces, Springer-Verlag, pp. 50–59, 111–118, 196–205, ISBN 978-0-387-96310-5

- Lehto, O.; Virtanen, K. I. (1973), Quasiconformal mappings in the plane, Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, 126 (Second ed.), Springer-Verlag

- Marden, A. (2007), Outer circles. An introduction to hyperbolic 3-manifolds, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-83974-7

- Mumford, D.; Series, C.; Wright, David (2002), Indra's pearls. The vision of Felix Klein, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-35253-6

- Pfluger, A. (1961), "Ueber die Konstruktion Riemannscher Flächen durch Verheftung", J. Indian Math. Soc. 24: 401–412

- Pommerenke, C. (1975), Univalent functions, with a chapter on quadratic differentials by Gerd Jensen, Studia Mathematica/Mathematische Lehrbücher, 15, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

- Rohde, S. (1991), "On conformal welding and quasicircles", Michigan Math. J. 38: 111–116, doi:10.1307/mmj/1029004266

- Sullivan, D. (1982), "Discrete conformal groups and measurable dynamics", Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 6: 57–73, doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-1982-14966-7

- Sullivan, D. (1985), "Quasiconformal homeomorphisms and dynamics, I, Solution of the Fatou-Julia problem on wandering domains", Annals of Mathematics 122 (2): 401–418, doi:10.2307/1971308

- Tienari, M. (1962), "Fortsetzung einer quasikonformen Abbildung über einen Jordanbogen", Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. Ser. A 321

- Smirnov, S. (2010), "Dimension of quasicircles", Acta Mathematica 205: 189–197, doi:10.1007/s11511-010-0053-8

|