Riemann surface

In mathematics, particularly in complex analysis, a Riemann surface is a one-dimensional complex manifold.

Loosely speaking, this means that any Riemann surface is formed by gluing together open subsets of the complex plane C using holomorphic gluing maps.

Examples of Riemann surfaces include graphs of multivalued functions like √z or log(z), e.g. the subset of pairs (z,w) ∈ C2 with w = log(z).

Every Riemann surface is a surface: a two-dimensional real manifold, but it contains more structure (specifically a complex structure). Conversely, a two-dimensional real manifold can be turned into a Riemann surface (usually in several inequivalent ways) if and only if it is orientable and metrizable. So the sphere and torus admit complex structures, but the Möbius strip, Klein bottle and real projective plane do not.

Every compact Riemann surface is a complex algebraic curve by Chow's theorem and the Riemann–Roch theorem.

Riemann surfaces were first studied by and are named after Bernhard Riemann.

Definitions

There are several equivalent definitions of a Riemann surface.

- A Riemann surface X is a complex manifold of complex dimension one. This means that X is a connected Hausdorff space that is endowed with an atlas of charts to the open unit disk of the complex plane: for every point x ∈ X there is a neighbourhood of x that is homeomorphic to the open unit disk of the complex plane, and the transition maps between two overlapping charts are required to be holomorphic.

- A Riemann surface is an oriented manifold of (real) dimension two – a two-sided surface – together with a conformal structure. Again, manifold means that locally at any point x of X, the space is homeomorphic to a subset of the real plane. The supplement "Riemann" signifies that X is endowed with an additional structure which allows angle measurement on the manifold, namely an equivalence class of so-called Riemannian metrics. Two such metrics are considered equivalent if the angles they measure are the same. Choosing an equivalence class of metrics on X is the additional datum of the conformal structure.

A complex structure gives rise to a conformal structure by choosing the standard Euclidean metric given on the complex plane and transporting it to X by means of the charts. Showing that a conformal structure determines a complex structure is more difficult.[1]

Examples

- The complex plane C is the most basic Riemann surface.

- Every open subset of the complex plane U ⊆ C is a Riemann surface. More generally, every non-empty open subset of a Riemann surface is a Riemann surface.

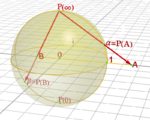

The Riemann sphere and stereographic projection. - The 2-sphere S2 has a unique Riemann surface structure, called the Riemann sphere. It has two open subsets which we identify with the complex plane by stereographically projecting from the North or South poles

On the intersection of these two open sets, composing one embedding with the inverse of the other gives

This transition map is holomorphic, so these two embeddings define a Riemann surface structure on S2. As sets, S2 = C ∪ {∞}. The Riemann sphere has another description, as the projective line CP1 = (C2 - {0})/C×.

A torus. - The 2-torus T2 has many different Riemann surface structures, all of the form C/(Z + τ Z) where τ is any complex non-real number. These are called elliptic curves.

- Important examples of non-compact Riemann surfaces are provided by analytic continuation.

Algebraic curves

- If P(x,y) is any complex polynomial in two variables, its vanishing locus

- {(x,y) : P(x,y) = 0} ⊆ C2

- Every elliptic curve is an algebraic curve, given by (the compactification of) the locus

- y2 = x3 + a x + b

- Likewise, genus g surfaces have Riemann surface structures, as (compactifications of) hyperelliptic surfaces

- y2 = Q(x),

-

f(z) = arcsin z

-

f(z) = log z

-

f(z) = z1/2

-

f(z) = z1/3

-

f(z) = z1/4

Further definitions and properties

As with any map between complex manifolds, a function f: M → N between two Riemann surfaces M and N is called holomorphic if for every chart g in the atlas of M and every chart h in the atlas of N, the map h ∘ f ∘ g−1 is holomorphic (as a function from C to C) wherever it is defined. The composition of two holomorphic maps is holomorphic. The two Riemann surfaces M and N are called biholomorphic (or conformally equivalent to emphasize the conformal point of view) if there exists a bijective holomorphic function from M to N whose inverse is also holomorphic (it turns out that the latter condition is automatic and can therefore be omitted). Two conformally equivalent Riemann surfaces are for all practical purposes identical.

Orientability

Each Riemann surface, being a complex manifold, is orientable as a real manifold. For complex charts f and g with transition function h = f(g−1(z)), h can be considered as a map from an open set of R2 to R2 whose Jacobian in a point z is just the real linear map given by multiplication by the complex number h'(z). However, the real determinant of multiplication by a complex number α equals |α|2, so the Jacobian of h has positive determinant. Consequently, the complex atlas is an oriented atlas.

Functions

Every non-compact Riemann surface admits non-constant holomorphic functions (with values in C). In fact, every non-compact Riemann surface is a Stein manifold.

In contrast, on a compact Riemann surface X every holomorphic function with values in C is constant due to the maximum principle. However, there always exist non-constant meromorphic functions (holomorphic functions with values in the Riemann sphere C ∪ {∞}). More precisely, the function field of X is a finite extension of C(t), the function field in one variable, i.e. any two meromorphic functions are algebraically dependent. This statement generalizes to higher dimensions, see (Siegel 1955). Meromorphic functions can be given fairly explicitly, in terms of Riemann theta functions and the Abel–Jacobi map of the surface.

Algebraicity

All compact Riemann surfaces are algebraic curves since they can be embedded into some . This follows from the Kodaira embedding theorem and the fact there exists a positive line bundle on any complex curve.[2]

Analytic vs. algebraic

The existence of non-constant meromorphic functions can be used to show that any compact Riemann surface is a projective variety, i.e. can be given by polynomial equations inside a projective space. Actually, it can be shown that every compact Riemann surface can be embedded into complex projective 3-space. This is a surprising theorem: Riemann surfaces are given by locally patching charts. If one global condition, namely compactness, is added, the surface is necessarily algebraic. This feature of Riemann surfaces allows one to study them with either the means of analytic or algebraic geometry. The corresponding statement for higher-dimensional objects is false, i.e. there are compact complex 2-manifolds which are not algebraic. On the other hand, every projective complex manifold is necessarily algebraic, see Chow's theorem.

As an example, consider the torus T := C/(Z + τ Z). The Weierstrass function belonging to the lattice Z + τ Z is a meromorphic function on T. This function and its derivative generate the function field of T. There is an equation

where the coefficients g2 and g3 depend on τ, thus giving an elliptic curve Eτ in the sense of algebraic geometry. Reversing this is accomplished by the j-invariant j(E), which can be used to determine τ and hence a torus.

Classification of Riemann surfaces

The set of all Riemann surfaces can be divided into three subsets: hyperbolic, parabolic and elliptic Riemann surfaces. Geometrically, these correspond to surfaces with negative, vanishing or positive constant sectional curvature. That is, every connected Riemann surface admits a unique complete 2-dimensional real Riemann metric with constant curvature equal to or which belongs to the conformal class of Riemannian metrics determined by its structure as a Riemann surface. This can be seen as a consequence of the existence of isothermal coordinates.

In complex analytic terms, the Poincaré–Koebe uniformization theorem (a generalization of the Riemann mapping theorem) states that every simply connected Riemann surface is conformally equivalent to one of the following:

- The Riemann sphere , which is isomorphic to the ;

- The complex plane ;

- The open disk which is isomorphic to the upper half-plane .

A Riemann surface is elliptic, parabolic or hyperbolic according to whether its universal cover is isomorphic to , or . The elements in each class admit a more precise description.

Elliptic Riemann surfaces

The Riemann sphere is the only example, as there is no group acting on it by biholomorphic transformations freely and properly discontinuously and so any Riemann surface whose universal cover is isomorphic to must itself be isomorphic to it.

Parabolic Riemann surfaces

If is a Riemann surface whose universal cover is isomorphic to the complex plane then it is isomorphic to one of the following surfaces:

- itself;

- The quotient ;

- A quotient where with .

Topologically there are only three types: the plane, the cylinder and the torus. But while in the two former case the (parabolic) Riemann surface structure is unique, varying the parameter in the third case gives non-isomorphic Riemann surfaces. The description by the parameter gives the Teichmüller space of "marked" Riemann surfaces (in addition to the Riemann surface structure one adds the topological data of a "marking", which can be seen as a fixed homeomorphism to the torus). To obtain the analytic moduli space (forgetting the marking) one takes the quotient of Teichmüller space by the mapping class group. In this case it is the modular curve.

Hyperbolic Riemann surfaces

In the remaining cases is a hyperbolic Riemann surface, that is isomorphic to a quotient of the upper half-plane by a Fuchsian group (this is sometimes called a Fuchsian model for the surface). The topological type of can be any orientable surface save the torus and sphere.

A case of particular interest is when is compact. Then its topological type is described by its genus . Its Teichmüller space and moduli space are -dimensional. A similar classification of Riemann surfaces of finite type (that is homeomorphic to a closed surface minus a finite number of points) can be given. However in general the moduli space of Riemann surfaces of infinite topological type is too large to admit such a description.

Maps between Riemann surfaces

The geometric classification is reflected in maps between Riemann surfaces, as detailed in Liouville's theorem and the Little Picard theorem: maps from hyperbolic to parabolic to elliptic are easy, but maps from elliptic to parabolic or parabolic to hyperbolic are very constrained (indeed, generally constant!). There are inclusions of the disc in the plane in the sphere: but any holomorphic map from the sphere to the plane is constant, any holomorphic map from the plane into the unit disk is constant (Liouville's theorem), and in fact any holomorphic map from the plane into the plane minus two points is constant (Little Picard theorem)!

Punctured spheres

These statements are clarified by considering the type of a Riemann sphere with a number of punctures. With no punctures, it is the Riemann sphere, which is elliptic. With one puncture, which can be placed at infinity, it is the complex plane, which is parabolic. With two punctures, it is the punctured plane or alternatively annulus or cylinder, which is parabolic. With three or more punctures, it is hyperbolic – compare pair of pants. One can map from one puncture to two, via the exponential map (which is entire and has an essential singularity at infinity, so not defined at infinity, and misses zero and infinity), but all maps from zero punctures to one or more, or one or two punctures to three or more are constant.

Ramified covering spaces

Continuing in this vein, compact Riemann surfaces can map to surfaces of lower genus, but not to higher genus, except as constant maps. This is because holomorphic and meromorphic maps behave locally like so non-constant maps are ramified covering maps, and for compact Riemann surfaces these are constrained by the Riemann–Hurwitz formula in algebraic topology, which relates the Euler characteristic of a space and a ramified cover.

For example, hyperbolic Riemann surfaces are ramified covering spaces of the sphere (they have non-constant meromorphic functions), but the sphere does not cover or otherwise map to higher genus surfaces, except as a constant.

Isometries of Riemann surfaces

The isometry group of a uniformized Riemann surface (equivalently, the conformal automorphism group) reflects its geometry:

- genus 0 – the isometry group of the sphere is the Möbius group of projective transforms of the complex line,

- the isometry group of the plane is the subgroup fixing infinity, and of the punctured plane is the subgroup leaving invariant the set containing only infinity and zero: either fixing them both, or interchanging them (1/z).

- the isometry group of the upper half-plane is the real Möbius group; this is conjugate to the automorphism group of the disk.

- genus 1 – the isometry group of a torus is in general translations (as an Abelian variety), though the square lattice and hexagonal lattice have addition symmetries from rotation by 90° and 60°.

- For genus g ≥ 2, the isometry group is finite, and has order at most 84(g − 1), by Hurwitz's automorphisms theorem; surfaces that realize this bound are called Hurwitz surfaces.

- It is known that every finite group can be realized as the full group of isometries of some Riemann surface.[3]

- For genus 2 the order is maximized by the Bolza surface, with order 48.

- For genus 3 the order is maximized by the Klein quartic, with order 168; this is the first Hurwitz surface, and its automorphism group is isomorphic to the unique simple group of order 168, which is the second-smallest non-abelian simple group. This group is isomorphic to both PSL(2,7) and PSL(3,2).

- For genus 4, Bring's surface is a highly symmetric surface.

- For genus 7 the order is maximized by the Macbeath surface, with order 504; this is the second Hurwitz surface, and its automorphism group is isomorphic to PSL(2,8), the fourth-smallest non-abelian simple group.

Function-theoretic classification

The classification scheme above is typically used by geometers. There is a different classification for Riemann surfaces which is typically used by complex analysts. It employs a different definition for "parabolic" and "hyperbolic". In this alternative classification scheme, a Riemann surface is called parabolic if there are no non-constant negative subharmonic functions on the surface and is otherwise called hyperbolic.[4][5] This class of hyperbolic surfaces is further subdivided into subclasses according to whether function spaces other than the negative subharmonic functions are degenerate, e.g. Riemann surfaces on which all bounded holomorphic functions are constant, or on which all bounded harmonic functions are constant, or on which all positive harmonic functions are constant, etc.

To avoid confusion, call the classification based on metrics of constant curvature the geometric classification, and the one based on degeneracy of function spaces the function-theoretic classification. For example, the Riemann surface consisting of "all complex numbers but 0 and 1" is parabolic in the function-theoretic classification but it is hyperbolic in the geometric classification.

See also

Theorems regarding Riemann surfaces

- Branching theorem

- Hurwitz's automorphisms theorem

- Identity theorem for Riemann surfaces

- Riemann–Roch theorem

- Riemann–Hurwitz formula

Notes

- ↑ See (Jost 2006, Ch. 3.11) for the construction of a corresponding complex structure.

- ↑ Nollet, Scott. "KODAIRA'S THEOREM AND COMPACTIFICATION OF MUMFORD'S MODULI SPACE Mg". http://faculty.tcu.edu/richardson/Seminars/scott4-15.pdf.

- ↑ Greenberg, L. (1974). "Maximal groups and signatures". Discontinuous Groups and Riemann Surfaces: Proceedings of the 1973 Conference at the University of Maryland. Ann. Math. Studies. 79. pp. 207–226. ISBN 0691081387. https://books.google.com/books?id=oriXEV6VoM0C&pg=PA207.

- ↑ Ahlfors, Lars; Sario, Leo (1960), Riemann Surfaces (1st ed.), Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 204

- ↑ Rodin, Burton; Sario, Leo (1968), Principal Functions (1st ed.), Princeton, New Jersey: D. Von Nostrand Company, Inc., p. 199, ISBN 9781468480382, https://books.google.com/books?id=_ZnlBwAAQBAJ&q=%22Riemann+surface%22

References

- Farkas, Hershel M.; Kra, Irwin (1980), Riemann Surfaces (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90465-8

- Pablo Arés Gastesi, Riemann Surfaces Book.

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, OCLC 13348052, esp. chapter IV.

- Jost, Jürgen (2006), Compact Riemann Surfaces, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 208–219, ISBN 978-3-540-33065-3

- Papadopoulos, Athanase, ed. (2007), Handbook of Teichmüller theory. Vol. I, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, 11, European Mathematical Society (EMS), Zürich, doi:10.4171/029, ISBN 978-3-03719-029-6, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00250897/file/athanase.pdf

- Lawton, Sean; Peterson, Elisha (2009), Papadopoulos, Athanase, ed., Handbook of Teichmüller theory. Vol. II, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, 13, European Mathematical Society (EMS), Zürich, doi:10.4171/055, ISBN 978-3-03719-055-5

- Papadopoulos, Athanase, ed. (2012), Handbook of Teichmüller theory. Vol. III, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, 19, European Mathematical Society (EMS), Zürich, doi:10.4171/103, ISBN 978-3-03719-103-3

- *Remmert, Reinhold (1998). "From Riemann Surfaces to Complex Spaces". Séminaires et Congrès.

- Siegel, Carl Ludwig (1955), "Meromorphe Funktionen auf kompakten analytischen Mannigfaltigkeiten", Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. II. Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse 1955: 71–77, ISSN 0065-5295

- Weyl, Hermann (2009), The concept of a Riemann surface (3rd ed.), New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-47004-7, https://archive.org/details/dieideederrieman00weyluoft

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Riemann surface", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/r082040

- McMullen, C.. "Complex Analysis on Riemann Surfaces Math 213b". Harvard University. https://people.math.harvard.edu/~ctm/home/text/class/harvard/213b/19/html/home/course/course.pdf.

|