Religion:Izumo-taisha

| Izumo-Taisha Izumo-Ōyashiro 出雲大社 | |

|---|---|

Monjin-no-yashiro, Amasaki-no-yashiro, Mimukai-no-yashiro, and honden | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Ōkuninushi, Kotoamatsukami |

| Festival | Reisai (taisairei) (May 14-16th) |

| Type | Chokusaisha Beppyo jinja, Shikinaisya Izumo no Kuni ichinomiya Kanpeitaisha |

| Location | |

| Location | 195 Kitsukihigashi, Taisha-machi, Izumo-shi, Shimane-ken 699-0701 |

| Geographic coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 35°24′07″N 132°41′08″E / 35.40194°N 132.68556°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Taisha-zukuri |

| Expression error: Unexpected < operator. | |

| Website | |

| www | |

Izumo-taisha (出雲大社, "Izumo Grand Shrine"), officially Izumo Ōyashiro, is one of the most ancient and important Shinto shrines in Japan . No record gives the date of establishment. Located in Izumo, Shimane Prefecture, it is home to two major festivals. It is dedicated to the god Ōkuninushi (大国主大神 Ōkuninushi no Ōkami), famous as the Shinto deity of marriage and to Kotoamatsukami, distinguishing heavenly kami. The shrine is believed by many to be the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan, even predating the Ise Grand Shrine.

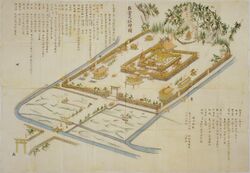

A style of architecture, taisha-zukuri, takes its name from the main hall of Izumo-taisha. That hall, and the attached buildings, were designated National Treasures of Japan in 1952. According to tradition, the hall was previously much taller than at present. The discovery in the year 2000 of the remains of enormous pillars has lent credence to this.

The shrine has been rebuilt every 60 to 70 years to maintain the power of the kami and maintain architectural techniques. This regular rebuilding process is called "Sengū" (遷宮) and has long been practiced at a handful of important Shinto shrines, the Ise Grand Shrine being rebuilt every 20 years.[1]

Several other buildings in the shrine compound are on the list of Important Cultural Properties of Japan.

Origins

According to the two oldest chronicles of Japan, the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, when Ninigi-no-Mikoto, grandson of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, descended from the heavens, the god Ōkuninushi granted his country to Ninigi-no-Mikoto. Amaterasu was much pleased by this action and she presented Izumo-taisha to Ōkuninushi.

At one time, the Japanese islands were controlled from Izumo, according to Shinto myths. Izumo, known as the realm of gods or the land of myths, is Izumo-taisha's province. Its main structure was originally constructed to glorify the great achievement of Ōkuninushi, considered the creator of Japan. Ōkuninushi was devoted to the building of the nation, in which he shared many joys and sorrows with the ancestors of the land. In addition to being the savior, Ōkuninushi is considered the guardian god and god of happiness, as well as the god who establishes good relationships.

According to the Nihon Shoki, the sun goddess Amaterasu said, "From now on, my descendants shall administer the affairs of state. You shall cast a spell of establishing good relationship over people to lead them a happy life. I will build your residence with colossal columns and thick and broad planks in the same architectural style as mine and name it Amenohisu-no-miya." The other gods were gathered and ordered by Amaterasu to build the grand palace at the foot of Mt. Uga.

There is no knowledge of exactly when Izumo-taisha was built, but a record compiled around 950 (Heian period) describes the shrine as the highest building, reaching approximately 48 meters, which exceeds in height the 45 meter-tall temple that enshrined the Great Image of Buddha, Tōdai-ji. This was due to early Shinto cosmology, when the people believed the gods (kami) were above the human world and belonged to the most extraordinary and majestic parts of nature. Therefore, Izumo-taisha could have been an attempt to create a place for the kami that would be above humans.

According to Kojiki, the legendary stories of old Japan, and Nihon Shoki, the chronicles of old Japan, Izumo-taisha was considered the largest wooden structure in Japan when it was originally constructed. Before being known as Izumo Ōyashiro or Izumo-taisha, the shrine was known as Okami-no-miya in Izumo, Itsukashinokami-no-miya, Kizuki-no-Oyashiro, Kizuki-no-miya, or Iwakumanoso-no-miya.

Evidence of the original Grand Shrine has been found. For example, part of one of the pillars for the structure was found: three cedar trees with a three-meter diameter at its base. It is on display at the shrine. Although there is not much early evidence one can see when visiting, there is a shop just before the main entrance that has a smaller scale model of the original main structure made by local college students.

History

During the Kamakura period, around 1200, the main structure was reduced in size. Then in 1744, the shrine was reconstructed to the present size of 24 meters high and 11 meters square at its base.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as travel became more common in Japan, the shrine became a central place of pilgrimage.

Since the shrine spirit was settled in the inner shrine in 1744, it has been relocated three times for renovation of the inner shrine, using a traditional ceremony. The relocations took place in 1809, 1881, and 1953.

From 1871 through 1946, the Izumo-taisha was officially designated one of the Kanpei-taisha (官幣大社), meaning that it stood in the first rank of government supported shrines.[2]

In April 2008, the spirit was moved to temporary housing in the front shrine of Izumo-taisha in preparation for the Heisei-period renovations. Izumo-taisha's inner shrine was opened to the public for the first time in 60 years in the summer of 2008. On completion of the renovations, Ōkuninushi was returned to the inner shrine in a ceremony attended by over 8,000 people, held on May 11, 2013.[3]

Architecture

File:Izumo Grand Shrine -scenes-2019 1 2.webm

The main structure of Izumo Oyashiro was built in the Taisha style, the oldest style of building shrines. An impressive sized gable-entrance structure is built for the main structure, which gave the name of The Great Shrine or The Grand Shrine. The main hall (honden) bears an enormous chigi (scissor-shaped finials at the front and back ends of the roof). A Japanese architecture book states, "In plan, the present Main Shrine resembles that of the Daijoe Shoden, built for the accession of each new Emperor. The main shrine at Izumo is thought, therefore, to preserve a floor plan characteristic of ancient domestic architecture" (Nishi & Hozumi, 1985, p. 41). From the view of architectures, the original height of the main structure of Izumo Taisha makes it difficult to study the historical building styles and methods. However, what is known is that from the construction of a building as big as the main structure, major problems were presented. Because of this, structural and stylistic changes occurred each time the main structure was rebuilt, which caused the outer form to be less reflective of the original construction of the main structure. Although the outside of the structure changed with each reconstruction, the floor plan remained virtually unchanged. The layout consists of nine support pillars arranged so that the inside is divided into four sections and causes the entrance to be off-centered. A significant characteristic that is common among most shrines is the symmetrical design, making the main structure of Izumo-taisha peculiar for its asymmetrical floor plan. The main structure was built more like a home rather than a shrine which suggests that between the people and kami there was a less formal relationship than at other shrines.

Kagura-den

Izumo-taisha's Kagura-den (神楽殿, Kagura hall) was first built in 1776 by the Senge family, Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko, or governor of Izumo, as a grand hall for performance of traditional rituals. It was rebuilt in 1981 to commemorate the centennial of the foundation of the Izumo Oyashiro-kyo order.

Traditional prayer by Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko, wedding ceremonies of believers, and the performances of sacred dance to ancient Japanese music involve the Oracle with 240 mats. Also worshipped with prayer is a frame with four dyed Kanji characters, meaning "the Oracle Filled with Aureole," by Prince Arisugawa above the altar.

The Kagura-den features the largest shimenawa (sacred straw rope) in Japan; it is 13.5 meters long and weighs around 5 tons. The rope is one of the most easily recognized and distinctive features of Izumo-taisha.

Shōkokan

The Shōkokan (彰古館) consists of two floors. The first floor is the reception office for Kaguraden. The second floor consists of a museum for important items.

Some items in the museum are items designated as national treasure and important cultural assets, like jewelry, household articles, paintings, swords, and musical instruments.

Considered most important in Shōkokan are a set of Japan's oldest wooden pestle and an igniting board and a small boat that was hollowed out of a piece of wood. The small boat was believed to have come from the upper stream of the Yoshino River, through the Seto Inland Sea, and to the Inasa Beach near Izumo-taisha.

Festivals

Festivals or matsuri in Izumo are times when people gather around the god to fulfill their wish to live a happy life. One of the most important in Izumo-taisha is the Imperial Festival held on May 14. Following the Imperial Festival is the Grand Festival on May 14 and 15.

Some other major festivals are January 1, Omike Festival; January 3, Fukumukae Festival; January 5, Beginning Sermon Festival; February 17, Kikoku (prayer for abundant crops) Festival; April 1, Kyoso Festival; June 1, Suzumidono Festival; and August 6–9 is Izumo Oyashiro-kyo Religion Festival.

In the tenth month of the traditional lunar calendar, a festival is held to welcome all the gods to Izumo Grand Shrine. It is believed that the gods convene at Izumo Shrine in October to discuss the coming year's marriages, deaths, and births. For this reason, people around the Izumo area call October kamiarizuki ("the month with gods"), but the rest of Japan calls October Kannazuki ("the month without gods").

Administrator's family

The descendants of Amenohohi-no-mikoto (天穂日命), the second son of Amaterasu-ōmikami (天照大御神), the sun goddess whose first son is the ancestor of the imperial family, have been, in the name of Izumo Kokuso (出雲国造) or governor of Izumo, taking over rituals because when Izumo-taisha was founded Amenohohi-no-mikoto rendered service to Okuninushi-no-kami. The family's conflict around 1340 made them separated into two lineages, Senge (千家) and Kitajima (北島).

After the separation those two families took the position of Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko by turns until the late 19th century. Shinto was reconstructed as modernized Japan's national religion in the late 19th century. In 1871, Izumo-taisha was designated as an Imperial-associated shrine and the government sent a new administrator so Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko families were no more the administrators of Izumo-taisha. Senge and Kitajima established their religious corporations respectively, Izumo-taisha-kyo (出雲大社教) by Senge and Izumo-kyo (出雲教) by Kitajima.

Under the Allied occupation after World War II, Shinto was separated from the government control and Izumo-taisha was reformed into a private shrine, then Senge and its Izumo-taisha-kyo took back the position of the administrator of Izumo-taisha. Takatoshi Senge (千家尊祀), the 83rd-generation Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko of Senge lineage, was chosen to be the chief priest of Izumo-taisha in 1947. He died in February 2002 at the age of 89.

Currently, the position of the administrator of Izumo-taisha is succeeded by Senge lineage. Its Izumo-taisha-kyo is better known nationwide and has more followers in total, "出雲大社 千家 尊統 (1998/8)", but locally Kitajima lineage and its Izumo-kyo has more followers around Izumo region. Kitajima is the more orthodox Izumo no Kuni no Miyatsuko. "出雲国造系統伝略 北島斉孝 (1898)". On October 5, 2014, Kunimaro Senge, eldest son of the current administrator Takamasa Senge, married Princess Noriko at the shrine. Princess Noriko is a daughter of the late Prince Takamado, a cousin of the now-Emperor Emeritus of Japan.[4]

Gallery

See also

- List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts: others)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (shrines)

- Ōkuninushi

- Ko-Shintō

- Shinto shrine

- Tourism in Japan

- Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

References

- ↑ 出雲大社 平成の大遷宮. Shimane Prefecture

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan, p. 125.

- ↑ "Special ceremony held at Izumo Taisha for 1st time in 60 years- 毎日jp(毎日新聞)". http://mainichi.jp/english/english/newsselect/news/20130511p2g00m0dm003000c.html.

- ↑ "Japantimes - Princess Noriko to wed" [1], Tokyo, 27 May 2014. Retrieved on 4 October 2014

General references

- Ancient Izumo in the spotlight. (2007, February 26, p. 19). The Daily Yomiuri (Tokyo), 1. Retrieved July 12, 2008, from the LexisNexis Academic database.

- Guide to Izumo Oyashiro. (n.d.). (Pamphlet available to visitors at the shrine)

- Izumo Shrine Find Points to Huge Ancient Building. (2000, April, p. 29). The Daily Yomiuri (Tokyo), 1. Retrieved July 12, 2008, from the LexisNexis Academic database.

- Lucas, B. (2002, May 7). History and Symbolism in Shinto Shrine Architecture[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]. Harvey Mudd College Web. Retrieved July 26, 2008

- Nishi, K., & Hozumi, K. (1985). What is Japanese Architecture?: A survey of traditional Japanese architecture, with a list of sites and a map. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 194887

- Senge, chief priest of Izumo Shrine, dies at 89. (2002, April 18). Japan Economic Newswire. Retrieved July 28, 2008, from the LexisNexis Academic database.

External links

|