Signed zero

Signed zero is zero with an associated sign. In ordinary arithmetic, the number 0 does not have a sign, so that −0, +0 and 0 are equivalent. However, in computing, some number representations allow for the existence of two zeros, often denoted by −0 (negative zero) and +0 (positive zero), regarded as equal by the numerical comparison operations but with possible different behaviors in particular operations. This occurs in the sign-magnitude and ones' complement signed number representations for integers, and in most floating-point number representations. The number 0 is usually encoded as +0, but can still be represented by +0, −0, or 0.

The IEEE 754 standard for floating-point arithmetic (presently used by most computers and programming languages that support floating-point numbers) requires both +0 and −0. Real arithmetic with signed zeros can be considered a variant of the extended real number line such that 1/−0 = −∞ and 1/+0 = +∞; division is undefined only for ±0/±0 and ±∞/±∞.

Negatively signed zero echoes the mathematical analysis concept of approaching 0 from below as a one-sided limit, which may be denoted by x → 0−, x → 0−, or x → ↑0. The notation "−0" may be used informally to denote a negative number that has been rounded to zero. The concept of negative zero also has some theoretical applications in statistical mechanics and other disciplines.

It is claimed that the inclusion of signed zero in IEEE 754 makes it much easier to achieve numerical accuracy in some critical problems,[1] in particular when computing with complex elementary functions.[2] On the other hand, the concept of signed zero runs contrary to the usual assumption made in mathematics that negative zero is the same value as zero. Representations that allow negative zero can be a source of errors in programs, if software developers do not take into account that while the two zero representations behave as equal under numeric comparisons, they yield different results in some operations.

Representations

Binary integer formats can use various encodings. In the widely used two's complement encoding, zero is unsigned. In a 1+7-bit sign-and-magnitude representation for integers, negative zero is represented by the bit string 1000 0000. In an 8-bit ones' complement representation, negative zero is represented by the bit string 1111 1111. In all these three encodings, positive or unsigned zero is represented by 0000 0000. However, the latter two encodings (with a signed zero) are uncommon for integer formats. The most common formats with a signed zero are floating-point formats (IEEE 754 formats or similar), described below.

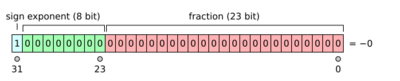

In IEEE 754 binary floating-point formats, zero values are represented by the biased exponent and significand both being zero. Negative zero has the sign bit set to one. One may obtain negative zero as the result of certain computations, for instance as the result of arithmetic underflow on a negative number (other results may also be possible), or −1.0 × 0.0, or simply as −0.0.

In IEEE 754 decimal floating-point formats, a negative zero is represented by an exponent being any valid exponent in the range for the format, the true significand being zero, and the sign bit being one.

Properties and handling

The IEEE 754 floating-point standard specifies the behavior of positive zero and negative zero under various operations. The outcome may depend on the current IEEE rounding mode settings.

Notation

In systems that include both signed and unsigned zeros, the notation and is sometimes used for signed zeros.

Arithmetic

Addition and multiplication are commutative, but there are some special rules that have to be followed, which mean the usual mathematical rules for algebraic simplification may not apply. The sign below shows the obtained floating-point results (it is not the usual equality operator).

The usual rule for signs is always followed when multiplying or dividing:

- (for different from ±∞)

- (for different from 0)

There are special rules for adding or subtracting signed zero:

- (for different from 0)

- (for any finite , −0 when rounding toward negative)

Because of negative zero (and also when the rounding mode is upward or downward), the expressions −(x − y) and (−x) − (−y), for floating-point variables x and y, cannot be replaced by y − x. However (−0) + x can be replaced by x with rounding to nearest (except when x can be a signaling NaN).

Some other special rules:

- [3]

- (follows the sign rule for division)

- (for non-zero , follows the sign rule for division)

- (Not a Number or interrupt for indeterminate form)

Division of a non-zero number by zero sets the divide by zero flag, and an operation producing a NaN sets the invalid operation flag. An exception handler is called if enabled for the corresponding flag.

Comparisons

According to the IEEE 754 standard, negative zero and positive zero should compare as equal with the usual (numerical) comparison operators, like the == operators of C and Java. In those languages, special programming tricks may be needed to distinguish the two values:

- Type punning the number to an integer type, so as to look at the sign bit in the bit pattern;

- using the ISO C

copysign()function (IEEE 754copySignoperation) to copy the sign of the zero to some non-zero number; - using the ISO C

signbit()macro (IEEE 754isSignMinusoperation) that returns whether the sign bit of a number is set; - taking the reciprocal of the zero to obtain either 1/+0 = +∞ or 1/−0 = −∞ (if the division by zero exception is not trapped).

Note: Casting to integral type will not always work, especially on two's complement systems.

However, some programming languages may provide alternative comparison operators that do distinguish the two zeros. This is the case, for example, of the equals method in Java's Double wrapper class.[4]

In rounded values

Informally, one may use the notation "−0" for a negative value that was rounded to zero. This notation may be useful when a negative sign is significant; for example, when tabulating Celsius temperatures, where a negative sign means below freezing.

In statistical mechanics

In statistical mechanics, one sometimes uses negative temperatures to describe systems with population inversion, which can be considered to have a temperature greater than positive infinity, because the coefficient of energy in the population distribution function is −1/Temperature. In this context, a temperature of −0 is a (theoretical) temperature larger than any other negative temperature, corresponding to the (theoretical) maximum conceivable extent of population inversion, the opposite extreme to +0.[5]

See also

- Line with two origins

- Extended real number line

References

- ↑ Kahan, William. "Branch Cuts for Complex Elementary Functions, or Much Ado About Nothing's Sign Bit". https://people.freebsd.org/~das/kahan86branch.pdf.

- ↑ William Kahan, Derivatives in the Complex z-plane, p. 10.

- ↑ Cowlishaw, Mike (7 April 2009). "Decimal Arithmetic: Arithmetic operations – square-root". speleotrove.com (IBM Corporation). https://speleotrove.com/decimal/daops.html#refsqrt.

- ↑ "Double". Oracle Help Center. http://java.sun.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/lang/Double.html#equals%28java.lang.Object%29.

- ↑ Kittel, Charles and Herbert Kroemer (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 462. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- "Floating point types". MSDN C# Language Specification. http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/en-us/csspec/html/vclrfcsharpspec_4_1_6.asp.

- "Division operator". MSDN C# Language Specification. http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/en-us/csspec/html/vclrfcsharpspec_7_7_2.asp.

- Thomas Wang (September 2000). "Java Floating-Point Number Intricacies". http://www.concentric.net/~Ttwang/tech/javafloat.htm.

- Mike Colishaw (28 July 2008). "Decimal Arithmetic Specification, version 1.68". https://speleotrove.com/decimal/decarith.html. – a decimal floating-point specification that includes negative zero

Further reading

- Michael Ingrassia. "Fortran 95 SIGN Change". Sun Developer Network. http://developers.sun.com/prodtech/cc/articles/sign.html. – the changes in the Fortran

SIGNfunction in Fortran 95 to accommodate negative zero - "JScript data types". MSDN JScript. http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/en-us/script56/html/js56jscondatatype.asp. – JScript's floating-point type with negative zero by definition

- Venners, Bill (1996-10-01). "Floating-point arithmetic". JavaWorld. https://www.infoworld.com/article/2077257/floating-point-arithmetic.html. – representation of negative zero in the Java virtual machine

- Bruce Dawson (25 February 2012). "Comparing floating point numbers, 2012 Edition". https://randomascii.wordpress.com/2012/02/25/comparing-floating-point-numbers-2012-edition/. – how to handle negative zero when comparing floating-point numbers

- John Walker. "Minus Zero". UNIVAC Memories. http://www.fourmilab.ch/documents/univac/minuszero.html. – one's complement numbers on the UNIVAC 1100 family computers

|