Social:Inupiaq language

| Inupiaq | |

|---|---|

| Iñupiatun, Inupiatun, Inupiaqtun | |

| Native to | United States , formerly Russia ; Northwest Territories of Canada |

| Region | Alaska; formerly Big Diomede Island |

| Ethnicity | 20,709 Iñupiat (2015) |

Native speakers | 2,144, 7% of ethnic population (2007)[1] |

Eskimo–Aleut

| |

| Latin (Iñupiaq alphabet) Iñupiaq Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Alaska[2], Northwest Territories (as Inuvialuktun, Uummarmiutun dialect) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ik |

| ISO 639-1 | ipk |

| ISO 639-3 | ipk – inclusive codeIndividual codes: esi – North Alaskan Inupiatunesk – Northwest Alaska Inupiatun |

| Glottolog | inup1234[3] |

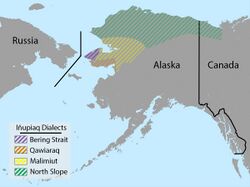

Inuit dialects. Inupiat dialects are orange (Northern Alaskan) and pink (Seward Peninsula). | |

Inupiaq /ɪˈnuːpiæk/, Inupiat /ɪˈnuːpiæt/, Inupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is a group of dialects of the Inuit languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, and part of the Northwest Territories. The Inupiat language is a member of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family, and is closely related to Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers.[4] It is considered a threatened language with most speakers at or above the age of 40.[5] Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska.[6]

The name is also rendered as Inupiatun, Iñupiatun, Iñupiaq, Inyupiaq,[7] Inyupiat,[7] Inyupeat,[8] Inyupik,[9] and Inupik.

The main varieties of the Iñupiaq language are Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq.

The Iñupiaq language has been in decline since contact with English in the late 19th century. American colonization and the legacy of boarding schools have created a situation today where a small minority of Iñupiat speak the Iñupiaq language. There is, however, revitalization work underway today in several communities.

History

The Iñupiaq language is an Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language, also known as Eskimo-Aleut, has been spoken in the northern regions of Alaska for as long as 5,000 years. Between 1,000 and 800 years ago, Inuit peoples migrated east from Alaska to Canada and Greenland, eventually occupying the entire Arctic coast and much of the surrounding inland areas. The Iñupiaq dialects are the most conservative forms of the Inuit language, with less linguistic change than the other Inuit languages.

In the mid to late 19th century, Russian, British, and American colonists would make contact with Inupiat people. In 1885, the American territorial government appointed Rev. Sheldon Jackson as General Agent of Education.[10] Under his administration, Inupiat people (and all Alaska Natives) were educated in English-only environments, forbidding the use of Iñupiaq and other indigenous languages of Alaska. After decades of English-only education, with strict punishment if heard speaking Iñupiaq, after the 1970s, most Inupiat did not pass the Iñupiaq language on to their children, for fear of them being punished for speaking their language.

In 1972, the Alaska Legislature passed legislation mandating that if "a [school is attended] by at least 15 pupils whose primary language is other than English, [then the school] shall have at least one teacher who is fluent in the native language".[11]

Today, the University of Alaska Fairbanks offers bachelor's degrees in Iñupiaq language and culture, while a preschool/kindergarten-level Iñupiaq immersion school named Nikaitchuat Ilisaġviat teaches grades PreK-1st grade in Kotzebue.

In 2014, Iñupiaq became an official language of the State of Alaska, alongside English and nineteen other indigenous languages.[6]

Dialects

There are four main dialect divisions and these can be organized within two larger dialect collections:[12]

Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq is spoken on the Seward Peninsula. Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq is spoken from the Northwest Arctic and North Slope regions of Alaska to the Mackenzie Delta in Northwest Territories, Canada.

| Dialect collection[12][14] | Dialect[12][14] | Subdialect[12][14] | Tribal nation(s) | Populated areas[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq | Bering Strait | Diomede | Iŋalikmiut | Little Diomede Island, Big Diomede Island until the late 1940s |

| Wales | Kiŋikmiut, Tapqaġmiut | Wales, Shishmaref, Brevig Mission | ||

| King Island | Ugiuvaŋmiut | King Island until the early 1960s, Nome | ||

| Qawiaraq | Teller | Siñiġaġmiut, Qawiaraġmiut | Teller, Shaktoolik | |

| Fish River | Iġałuiŋmiut | White Mountain, Golovin | ||

| Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq | Malimiutun | Kobuk | Kuuŋmiut, Kiitaaŋmiut [Kiitaaġmiut], Siilim Kaŋianiġmiut, Nuurviŋmiut, Kuuvaum Kaŋiaġmiut, Akuniġmiut, Nuataaġmiut, Napaaqtuġmiut, Kivalliñiġmiut[15] | Kobuk River Valley, Selawik |

| Kotzebue | Pittaġmiut, Kaŋiġmiut, Qikiqtaġruŋmiut[15] | Kotzebue, Noatak | ||

| North Slope / Siḷaliñiġmiutun | Common North Slope | Utuqqaġmiut, Siliñaġmiut [Kukparuŋmiut and Kuuŋmiut], Kakligmiut [Sitarumiut, Utqiaġvigmiut and Nuvugmiut], Kuulugruaġmiut, Ikpikpagmiut, Kuukpigmiut [Kañianermiut, Killinermiut and Kagmalirmiut][15][16] | ||

| Point Hope[13] | Tikiġaġmiut | Point Hope[13] | ||

| Point Barrow | Utqiaġvigmiut | |||

| Anaktuvuk Pass | Nunamiut | Anaktuvuk Pass | ||

| Uummarmiutun | Uummarmiut | Aklavik (Canada), Inuvik (Canada) |

Extra geographical information:

Bering Strait dialect:

The native population of the Big Diomede Island was moved to the Siberian mainland after World War II. The following generation of the population spoke Central Siberian Yupik or Russian.[14] The entire population of King Island moved to Nome in the early 1960s.[14] The Bering Strait dialect might also be spoken in Teller on the Seward Peninsula.[13]

Qawiaraq dialect:

A dialect of Qawiaraq is spoken in Nome.[13][14] A dialect of Qawariaq may also be spoken in Koyuk,[14] Mary's Igloo, Council, and Elim.[13] The Teller sub-dialect may be spoken in Unalakleet.[13][14]

Malimiutun dialect:

Both sub-dialects can be found in Buckland, Koyuk, Shaktoolik, and Unalakleet.[13][14] A dialect of Malimiutun may be spoken in Deering, Kiana, Noorvik, Shungnak, and Ambler.[13] The Malimiutun sub-dialects have also been classified as "Southern Malimiut" (found in Koyuk, Shaktoolik, and Unalakleet) and "Northern Malimiut" found in "other villages".[13]

North Slope dialect:

Common North Slope is "a mix of the various speech forms formerly used in the area".[14] The Point Barrow dialect was "spoken only by a few elders" in 2010.[14] A dialect of North Slope is also spoken in Kivalina, Point Lay, Wainwright, Atqasuk, Utqiagvik, Nuiqsut, and Barter Island.[13]

Phonology

Iñupiaq dialects differ widely between consonants used. However, consonant clusters of more than two consonants in a row do not occur. A word may not begin nor end with a consonant cluster.[13]

All Iñupiaq dialects have three basic vowel qualities: /a i u/.[13][14] There is currently no instrumental work to determine what allophones may be linked to these vowels. All three vowels can be long or short, giving rise to a system of six phonemic vowels /a aː i iː u uː/. Long vowels are represented by double letters in the orthography: ⟨aa⟩, ⟨ii⟩, ⟨uu⟩.[13] The following diphthongs occur: /ai ia au ua iu ui/.[13][17] No more than two vowels occur in a sequence in Iñupiaq.[13]

The Bering strait dialect has a forth vowel /e/, which preserves the fourth proto-Eskimo vowel reconstructed as */ə/. [13][14] In the other dialects, proto-Eskimo */e/ has merged with the closed front vowel /i/. The merged /i/ is referred to as the “strong /i/”, which causes palatalization when preceding consonant clusters in the North Slope dialect (see section on palatalization below). The other /i/ is referred to as “the weak /i/”. Weak and strong /i/s are not differentiated in orthography,[13] making it impossible to tell which ⟨i⟩ represents palatalization “short of looking at other processes which depend on the distinction between two i's or else examining data from other Eskimo languages”.[18] However, it can be assumed that, within a word, if a palatal consonant is preceded by an ⟨i⟩, it is strong. If an alveolar consonant is preceded by an ⟨i⟩, it is weak.[18]

Words begin with a stop (with the exception of the palatal stop /c/), the fricative /s/, nasals /m n/, with a vowel, or the semivowel /j/. Loanwords, proper names, and exclamations may begin with any segment in both the Seward Peninsula dialects and the North Slope dialects [13] . In the Uummarmiutun dialect words can also begin with /h/. For example, the word for "ear" in North Slope and Little Diomede Island dialects is siun whereas in Uummarmiutun it is hiun.

A word may end in any nasal sound (except for the /ɴ/ found in North Slope), in the stops /t k q/ or in a vowel. In the North Slope dialect if a word ends with an m, and the next word begins with a stop, the m is pronounced /p/, as in aġnam tupiŋa, pronounced /aʁnap tupiŋa/[13]

Very little information of the prosody of Iñupiaq has been collected. However, "fundamental frequency (Hz), intensity (dB), loudness (sones), and spectral tilt (phons - dB) may be important" in Malimiutun.[19] Likewise, "duration is not likely to be important in Malimiut Iñupiaq stress/syllable prominence".[19]

North Slope Iñupiaq:

For North Slope Iñupiaq[12][13][20]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Retroflex | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | Voiceless | /p/ | /t/ | /c/ [19] | /k/ | /q/ | /ʔ/ * | |

| Voiced | ||||||||

| Nasals | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /ɴ/ | |||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | /f/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /x/ | /χ/ | /h/ | |

| voiced | /v/ | /ʐ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | ||||

| Lateral | voiceless | /ɬ/ | /ʎ̥/ * | |||||

| voiced | /l/ | /ʎ/ | ||||||

| Approximant | /j/ | |||||||

The voiceless stops /p/ /t/ /k/ and /q/ are not aspirated.[13] This may or may not be true for other dialects as well.

* The sound /ʎ̥/ might actually be the sound /ɬʲ/. The sound /ʔ/ might not exist. Recent learners of the language, and heritage speakers are replacing the sound /ʐ/ (written in Iñupiaq as "r") with the American English /ɹ/ sound.[19]

/c/ is derived from a palatalized and unreleased /t/.[13]

Assimilation:[13]

Two consonants cannot appear together unless they share the manner of articulation (in this case treating the lateral and approximate consonants as fricatives). The only exception to this rule is having a voiced fricative consonant appear with a nasal consonant. Since all stops in North Slope are voiceless, a lot of needed assimilation arises from having to assimilate a voiceless stop to a voiced consonant.

This process is realized by assimilating the first consonant in the cluster to a consonant that: 1) has the same (or closest possible) area of articulation as the consonant being assimilated; and 2) has the same manner of articulation as the second consonant that it is assimilating to. If the second consonant is a lateral or approximate, the first consonant will assimilate to a lateral or approximate if possible. If not the first consonant will assimilate to a fricative. Therefore:

| North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| Kamik + niaq + te → kamigniaqtuq

or → kamiŋniaqtuq |

/kn/ → /ɣn/

or → /ŋn/ |

"to put boots on" + "will" + "he" → he will put the boots on |

| iḷisaq + niaq + tuq → iḷisaġniaqtuq | /qn/ → /ʁn/

or → /ɴ/ * |

"to study" + "will" + "he" → he will study |

| aqpat + niaq + tuq → aqpanniaqtuq | /tn/ → /nn/ | "to run" + "will" + "he" → he will run |

| makit + man → makinman | /tm/ → /nm/ | "to stand up" + "when he" → When he stood up |

| makit + łuni → makiłłuni | /tɬ/ → /ɬɬ/ | "to stand" + "by ---ing" → standing up, he ... |

* The sound /ɴ/ is not represented in the orthography. Therefore the spelling ġn can be pronounced as /ʁn/ or /ɴn/. In both examples 1 and 2, since voiced fricatives can appear with nasal consonants, both consonant clusters are possible.

The stops /t̚ʲ/ and /t/ do not have a corresponding voiced fricative, therefore they will assimilate to the closest possible area of articulation. In this case, the /t̚ʲ/ will assimilate to the voiced approximant /j/. The /t/ will assimilate into a /ʐ/. Therefore:

| North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| siksriit + guuq → siksriiyguuq | /t̚ʲɣ/ → /jɣ/ | "squirrels" + "it is said that" → it is said that squirrels |

| aqpat + vik → aqparvik | /tv/ → /ʐv/ | "to run" + "place" → race track |

In the case of the second consonant being a lateral, the lateral will again be treated as a fricative. Therefore:

| North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| aġnam + lu → aġnamlu

or → aġnavlu |

/ml/ → /ml/

or → /vl/ |

"(of) the woman" + "and" → and (of) the woman |

| aŋun + lu → aŋunlu

or → aŋullu |

/nl/ → /nl/

or → /vl/ |

"the man" + "and" → "and the man |

Since voiced fricatives can appear with nasal consonants, both consonant clusters are possible.

The sounds /f/ /x/ and /χ/ are not represented in the orthography (unless they occur alone between vowels). Therefore, like the /ɴn/ example shown above, assimilation still occurs while the spelling remains the same. Therefore:

| North Slope | IPA (pronunciation) | English |

|---|---|---|

| miqłiqtuq | /qɬ/ → /χɬ/ | child |

| siksrik | /kʂ/ → /xʂ/ | squirrel |

| tavsi | /vs/ → /fs/ | belt |

These general features of assimilation are not shared with Uummarmiut, Malimiutun, or the Seward Peninsula dialects. Malimiutun and the Seward Peninsula dialects "preserve[] voiceless stops (k, p, q, t) when they are etymological (i.e. when they belong to the original word-base)".[14] Compare:

| North Slope | Malimiutun | Seward Peninsula dialects | Uummarmiut | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nivliqsuq | nipliqsuq | nivliraqtuq | makes a sound | |

| igniq | ikniq | ikniq | fire | |

| annuġaak | atnuġaak | atar̂aaq | garment |

Palatalization[13]

The following patterns of palatalization can occur in North Slope Iñupiaq: /t/ → /t̚ʲ/ /tʃ/ or /s/; /ɬ/ → /ʎ̥/; /l/ → /ʎ/; and /n/ → /ɲ/. Palatalization only occurs when one of these four alveolars is preceded by a strong i. Compare:

| Type of I | North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| strong | qimmiq → qimmit | /qimːiq/ → /qimːit̚ʲ/ | dog → dogs |

| weak | tumi → tumit | /tumi/ → /tumit/ | footprint → footprints |

| strong | iġġi → iġġiḷu | /iʁːi/ → /iʁːiʎu/ | mountain → and a mountain |

| weak | tumi → tumilu | /tumi/ → /tumilu/ | footprint → and a footprint |

Please note that the sound /t̚ʲ/ does not have its own letter, and is simply spelled with a T t. The IPA transcription of the above vowels may be incorrect.

If a t that precedes a vowel is palatalized, it will become an /s/. The strong i affects the entire consonant cluster, palatalizing all consonants that can be palatalized within the cluster. Therefore:

| Type of I | North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| strong | qimmiq + tigun → qimmisigun | /qimmiq/ + /tiɣun/ → /qimːisiɣun/ | dog + amongst the plural things → amongst, in the midst of dogs |

| strong | puqik + tuq → puqiksuq | /puqik/ + /tuq/ → /puqiksuq/ | to be smart + she/he/it → she/he/it is smart |

Note in the first example, due to the nature of the suffix, the /q/ is dropped. Like the first set of examples, the IPA transcriptions of above vowels may be incorrect.

If a strong i precedes geminate consonant, the entire elongated consonant becomes palatalized. For Example: niġḷḷaturuq and tikiññiaqtuq.

Further strong versus weak i processes[13]

The strong i can be paired with a vowel. The weak i on the other hand cannot.[18] The weak i will become an a if it is paired with another vowel, or if the consonant before the i becomes geminate. This rule may or may not apply to other dialects. Therefore:

| Type of I | North Slope | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| weak | tumi → tumaa | /tumi/ → /tumaː/ | footprint → her/his footprint |

| strong | qimmiq → qimmia | /qimːiq/ → /qimːia/ | dog → her/his dog |

| weak | kamik → kammak | /kamik/ → /kamːak/ | boot → two boots |

Like the first two sets of examples, the IPA transcriptions of above vowels may be incorrect.

Uummarmiutun sub-dialect:

For the Uummarmiutun sub-dialect:[17]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Retroflex | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | Voiceless | /p/ | /t/ | /tʃ/ | /k/ | /q/ | /ʔ/ * | |

| Voiced | /dʒ/ | |||||||

| Nasals | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | ||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | /f/ | /x/ | /χ/ | /h/ | |||

| voiced | /v/ | /ʐ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | ||||

| Lateral | voiceless | /ɬ/ | ||||||

| voiced | /l/ | |||||||

| approximant | /j/ | |||||||

* Ambiguities: This sound might exist in the Uummarmiutun sub dialect.

Phonological rules

The following are the phonological rules:[17] The /f/ is always found as a geminate.

The /j/ cannot be geminated, and is always found between vowels or preceded by /v/. In rare cases it can be found at the beginning of a word.

The /h/ is never geminate, and can appear as the first letter of the word, between vowels, or preceded by /k/ /ɬ/ or /q/.

The /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ are always geminate or preceded by a /t/.

The /ʐ/ can appear between vowels, preceded by consonants /ɣ/ /k/ /q/ /ʁ/ /t/ or /v/, or it can be followed by /ɣ/, /v/, /ʁ/.

Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq:

For Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq:[12]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Retroflex | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | Voiceless | /p/ | /t/ | /tʃ/ | /k/ | /q/ | /ʔ/ | |

| Voiced | /b/ | |||||||

| Nasals | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | |||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /h/ | ||||

| voiced | /v/ | /z/ | /ʐ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | |||

| Lateral | voiceless | /ɬ/ | ||||||

| voiced | /l/ | |||||||

| approximant | /w/ | /j/ | /ɻ/ | |||||

Unlike the other Iñupiaq dialects, the Seward Peninsula dialect has a mid central vowel e (see the beginning of the phonology section for more information).

Gemination

In North Slope Iñupiaq, all consonants represented by orthography can be geminated, except for the sounds /tʃ/ /s/ /h/ and /ʂ/.[13] Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq (using vocabulary from the Little Diomede Island as a representative sample) likewise can have all consonants represented by orthography appear as geminates, except for /b/ /h/ /ŋ/ /ʂ/ /w/ /z/ and /ʐ/. Gemination is caused by suffixes being added to a consonant, so that the consonant is found between two vowels.[13]

Writing systems

Iñupiaq was first written when explorers first arrived in Alaska and began recording words in the native languages. They wrote by adapting the letters of their own language to writing the sounds they were recording. Spelling was often inconsistent, since the writers invented it as they wrote. Unfamiliar sounds were often confused with other sounds, so that, for example, 'q' was often not distinguished from 'k' and long consonants or vowels were not distinguished from short ones.

Along with the Alaskan and Siberian Yupik, the Inupiat eventually adopted the Latin script (Qaliujaaqpait) that Moravian missionaries developed in Greenland and Labrador. Native Alaskans also developed a system of pictographs,[which?] which, however, died with its creators.[21]

In 1946, Roy Ahmaogak, an Iñupiaq Presbyterian minister from Utqiagvik, worked with Eugene Nida, a member of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, to develop the current Iñupiaq alphabet based on the Latin script. Although some changes have been made since its origin—most notably the change from 'ḳ' to 'q'—the essential system was accurate and is still in use.

| A a | Ch ch | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ḷ ḷ | Ł ł | Ł̣ ł̣ | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ḷa | ła | ł̣a | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ʎ/ | /ɬ/ | /ʎ̥/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ŋ ŋ | P p | Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

Extra letter for Kobuk dialect: ’ /ʔ/

| A a | B b | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m | N n | Ŋ ŋ | P p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ba | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ła | ma | na | ŋa | pa |

| /a/ | /b/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ |

| Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | W w | Y y | Z z | Zr zr | ' | |

| qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | wa | ya | za | zra | ||

| /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /w/ | /j/ | /z/ | /ʐ/ | /ʔ/ |

Extra letters for specific dialects:

| A a | Ch ch | F f | G g | H h | Dj dj | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | fa | ga | ha | dja | i | ka | la | ła | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /f/ | /ɣ/ | /h/ | /dʒ/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ng ng | P p | Q q | R r | R̂ r̂ | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | r̂a | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ʁ/ | /ʐ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

Morphosyntax

Due the number of dialects and complexity of Iñupiaq Morphosyntax, the following section will be discussing Malimiutun morphosyntax as a representative example. Any examples from other dialects will be marked as such.

Iñupiaq is a polysynthetic language, meaning that words can be extremely long, consisting of one of three stems (verb stem, noun stem, and demonstrative stem) along with one or more of three endings (postbases, (grammatical) endings, and enclitics).[13] The stem gives meaning to the word, whereas endings give information regarding case, mood, tense, person, plurality, etc. The stem can appear as simple (having no postbases) or complex (having one or more postbases). In Iñupiaq a "postbase serves somewhat the same functions that adverbs, adjectives, prefixes, and suffixes do in English" along with marking various types of tenses.[13] There are six word classes in Malimiut Inñupiaq: nouns (see Nominal Morphology), verbs (see Verbal Morphology), adverbs, pronouns, conjunctions, and interjections. All demonstratives are classified as either adverbs or pronouns.[19]

Nominal morphology

The Iñupiaq category of number distinguishes singular, dual, and plural. The language works on an Ergative-Absolutive system, where nouns are inflected for number, several cases, and possession.[13] Iñupiaq (Malimiutun) has nine cases, two core cases (ergative and absolutive) and seven oblique cases (instrumental, allative, ablative, locative, perlative, similative and vocative).[19] North Slope Iñupiaq does not have the vocative case.[13] Iñupiaq does not have a category of gender and articles.[citation needed]

Iñupiaq Nouns can likewise be classified by Wolf A. Seiler's seven noun classes.[19][23] These noun classes are "based on morphological behavior. [They] ... have no semantic basis but are useful for case formation ... stems of various classes interact with suffixes differently".[19]

Due to the nature of the morphology, a single case can take on up to 12 endings (ignoring the fact that realization of these endings can change depending on noun class). For example, the possessed ergative ending for a class 1a noun can take on the endings: -ma, ‑mnuk, ‑pta, ‑vich, ‑ptik, -psi, -mi, -mik, -miŋ, -ŋan, -ŋaknik, and ‑ŋata. Therefore, only general features will be described below. For an extensive list on case endings, please see Seiler 2012, Appendix 4, 6, and 7.[23]

Absolutive case/noun stems

The subject of an intransitive sentence or the object of a transitive sentence take on the absolutive case. This case is likewise used to mark the basic form of a noun. Therefore, all the singular, dual, and plural absolutive forms serve as stems for the other oblique cases.[13] The following chart is verified of both Malimiutun and North Slope Iñupiaq.

| Endings | |

|---|---|

| singular | -q, -k, -n, or any vowel |

| dual | -k |

| plural | -t |

If the singular absolutive form ends with -n, it has the underlying form of -ti /tə/. This form will show in the absolutive dual and plural forms. Therefore:

tiŋmisuun (airplane) → tiŋmisuutik (two airplanes) and tiŋmisuutit (multiple airplanes)

Regarding nouns that have an underlying /ə/ (weak i), the i will change to an a and the previous consonant will be geminated in the dual form. Therefore:

Kamik (boot) → kammak (two boots).

If the singular form of the noun ends with -k, the preceding vowel will be elongated. Therefore:

savik (knife) → saviik (two knives).

On occasion, the consonant preceding the final vowel is also geminated, though exact phonological reasoning is unclear.[19]

Ergative case

The ergative case is often referred to as the Relative Case in Iñupiaq sources.[13] This case marks the subject of a transitive sentence or a genitive (possessive) noun phrase. For non-possessed noun phrases, the noun is marked only if it is a third person singular. The unmarked nouns leave ambiguity as to who/what is the subject and object. This can be resolved only through context.[13][19] Possessed noun phrases and noun phrases expressing genitive are marked in ergative for all persons.[19]

| Endings | Allophones |

|---|---|

| -m | -um, -im |

This suffix applies to all singular unpossessed nouns in the ergative case.

| Example | English |

|---|---|

| aŋun → aŋutim | man → man (ergative) |

| aŋatchiaq → aŋatchiaŋma | uncle → my two uncles (ergative) |

Please note the underlying /tə/ form in the first example.

Instrumental case

This case is also referred to as the modalis case. This case has a wide range of uses described below:

| Usage of instrumental[19] | Iñupiaq | English | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marks nouns that are means by which the subject achieves something (see instrumental) | Aŋuniaqtim aġviġluaq tuqutkaa nauligamik. | [hunter (ergative)] [gray wale (absolutive)] [kill—indicative; third person singular subject and object] [harpoon (using it as a tool to)] | The hunter killed the gray whale with a harpoon. |

| Marks the apparent patient (grammatical object upon which the action was carried out) of syntactically intransitive verbs | Miñułiqtugut umiamik. | [paint—indicative; third person singular object] [boat (having the previous verb being done to it)] | We're painting a boat. |

| Marks information new to the narrative (when the noun is first mentioned in a narrative)

Marks indefinite objects of some transitive verbs |

Tuyuġaat tuyuutimik. | [send—indicative; third person plural subject, third person singular object] [letter (new piece of information)] | They sent him a letter. |

| Marks the specification of a noun's meaning to incorporate the meaning of another noun (without incorporating both nouns into a single word) (Modalis of specification)[13] | Niġiqaqtuguk tuttumik. | [food—have—indicative; first person dual subject] [caribou (specifying that the caribou is food by referring to the previous noun)] | We (dual) have (food) caribou for food. |

| Qavsiñik paniqaqpit? | [how many (of the following noun)] [daughter—have] | How many daughters do you have? |

| Endings | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Iñupiaq | English | ||

| singular | -mik | Kamik → kamiŋmik | boot → (with a) boot |

| dual | [dual absolutive stem] -nik | kammak → kammaŋnik | (two) boots → (with two) boots |

| plural | [singular absolutive stem] -nik | kamik → kamiŋnik | boot → (with multiple) boots |

Since the ending is the same for both dual and plural, different stems are used. In all the examples the k is assimilated to an ŋ.

Allative case

The allative case is also referred to as the terminalis case. The uses of this case are described below:[19]

| Usage of Allative[19] | Iñupiaq | English | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used to signify motion or an action directed towards a goal[13] | Qaliŋaum quppiġaaq atauksritchaa Nauyamun. | [Qaliŋak (Ergative)] [coat (absolutive)] [lend—indicative; third person singular subject and object] [Nauyaq (towards his direction/to him)] | Qaliŋak lent a coat to Nauyaq |

| Isiqtuq iglumun. | [enter—indicative; third person singular] [house (into)] | He went into the house | |

| Signifies that the statement is for the purpose of the marked noun | Niġiqpaŋmun niqłiuqġñiaqtugut. | [(for the purpose of) feast ] [prepare.a.meal—future—Indicative; first person plural subject] | We will prepare a meal for the feast. |

| Signifies the beneficiary of the statement | Piquum uligruat paipiuranun qiḷaŋniqsuq. | [Piquk (ergative)] [blanket (absolutive) plural] [(for) baby plural] [knit—indicative; third person singular] | Evidently Piquk knits blankets for babies. |

| Marks the noun that is being addressed to | Qaliŋaŋmun uqautirut | [(to) Qaliŋaŋmun] [tell—indicative; third person plural subject] | They (plural) told Qaliŋak. |

| Endings | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Iñupiaq | English | ||

| singular | -mun | aġnauraq → aġnauramun | girl → (to the) girl |

| dual | [dual absolutive stem] -nun | aġnaurak → aġnauraŋ* | (two) girls → (with two) girls |

| plural | [singular absolutive stem] -nun | aġnauraq → aġnauranun | girl → (to the two) girls |

*It is unclear as to whether this example is regular for the dual form or not.

Verbal morphology

Again, Malimiutun Iñupiaq is used as a representative example in this section. The basic structure of the verb is [(verb) + (derivational suffix) + (inflectional suffix) + (enclitic)], although Lanz (2010) argues that this approach is insufficient since it "forces one to analyze ... optional ... suffixes".[19] Every verb has an obligatory inflection for person, number, and mood (all marked by a single suffix), and can have other inflectional suffixes such as tense, aspect, modality, and various suffixes carrying adverbial functions.[19]

Tense

Tense marking is always optional. The only explicitly marked tense is the future tense. Past and present tense cannot be marked and are always implied. All verbs can be marked through adverbs to show relative time (using words such as "yesterday" or "tomorrow"). If neither of these markings is present, the verb can imply a past, present, or future tense.[19]

| Tense | Iñupiaq | Transcription | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Uqaqsiitigun uqaqtuguk. | [telephone] [we dual talk] | We (two) talk on the phone. |

| Future | Uqaqsiitigun uqaġisiruguk. | [telephone] [we dual future talk] | We (two) will talk on the phone. |

| Future (implied) | Iġñivaluktuq aakauraġa uvlaakun. | [give birth probably] [my sister] [tomorrow] | My sister (will) give(s) birth tomorrow. (the future tense "will" is implied by the word tomorrow) |

Aspect

Marking aspect is optional in Iñupiaq verbs. Both North Slope and Malimiut Iñupiaq have a perfective versus imperfective distinction in aspect, along with other distinctions such as: frequentative (-ataq; "to repeatedly verb"), habitual (-suu; "to always, habitually verb"), inchoative (-łhiñaaq; "about to verb"), and intentional (-saġuma; "intend to verb"). The aspect suffix can be found after the verb root and before or within the obligatory person-number-mood suffix.[19]

Mood

Iñupiaq has the following moods: Indicative, Interrogative, Imperative (positive, negative), Coordinative, and Conditional.[19][23] Participles are sometimes classified as a mood.[19]

| Mood | Usage | Example | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iñupiaq | Literal translation | English | Notes | ||

| Indicative | Declarative statements | aŋuniaqtit siñiktut. | (hunt-nominalized-plural) + (sleep-3rd person; indicative) | The hunters are sleeping. | |

| Participles | Creating relative clauses | Putu aŋutauruq umiaqaqtuaq. | (Putu) + (young-man) + (boat-have-3rd person; participle) | Putu is a man who owns a boat. | "who owns a boat" is one word, where the meaning of the English "who" is implied through the case. |

| Interrogative | Formation of yes/no questions and content questions | Puuvratlavich. | (swim-POT- 2nd person; interrogative) | Can you (singular) swim? | Yes/no question |

| Suvisik? | (what- 2nd person-dual; interrogative) | What are you two doing? | Content question (this is a single word) | ||

| Imperative | A command | Naalaġiñ! | (listen-2nd person-singular; imperative) | Listen! | |

| Conditionals | Conditional and hypothetical statements | Kakkama niġiŋaruŋa. | (hungry-1st person-singular, conditional, perfective) + (eat-perfective-1st person-singular, indicative) | When I got hungry, I ate. | Conditional statement. The verb "eat" is in the indicative mood because it is simply a declarative statement. |

| Kaakkumi niġiñiaqtuŋa. | (hungry-1st person-singular; conditional; imperfective) + (eat-future-1st person-singular, indicative) | If I get hungry, I will eat. | Hypothetical statement. The verb "eat" is in the indicative mood because it is simply a statement. | ||

| Coordinative | Formation of dependent clauses that function as modifiers of independent clauses | Agliqiłuŋa niġiruŋa. | (read- 1st person-singularġ coordinative) + (eat- 1st person-singular, indicative) | [While] reading, I eat. | The coordinative case on the verb "read" signifies that the verb is happening at the same time as the main clause ("eat" - marked by indicative because it is simply a declarative statement). |

Indicative mood endings can be transitive or intransitive, as seen in the table below.

| Indicative intransitive endings | Indicative transitive endings | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBJECT | |||||||||||||||

| Mood marker | 3s | 3d | 3p | 2s | 2d | 2p | 1s | 1d | 1p | ||||||

| +t/ru | ŋa

guk gut |

1S

1D 1P |

S

U B J E C T |

+kI/gI | ga

kpuk kput |

kka

← ← |

tka

vuk vut |

kpiñ

↓ visigiñ |

vsik

↓ ↓ |

vsI

↓ ↓ |

1S

1D 1P |

S

U B J E C T | |||

| tin

sik sI |

2S

2D 2P |

n

ksik ksi |

kkiñ

← ← |

tin

sik si |

ŋma

vsiŋŋa vsiñŋa |

vsiguk

↓ ↓ |

vsigut

↓ ↓ |

2S

2D 2P | |||||||

| q

k t |

3S

SD 3P |

+ka/ga | a

ak at |

ik

↓← ↓← |

I

↓ It |

atin

↓ ↓ |

asik

↓ ↓ |

asI

↓ ↓ |

aŋa

aŋŋa aŋŋa |

atiguk

↓ ↓ |

atigut

↓ ↓ |

3S

3D 3P | |||

Syntax

Nearly all syntactic operations in the Malimiut dialect of Iñiupiaq—and Inuit languages and dialects in general—are carried out via morphological means." [19]

The language aligns to an ergative-absolutive case system, which is mainly shown through nominal case markings and verb agreement (see above).[19]

The basic word order is subject-object-verb. However, word order is flexible and both subject and/or object can be omitted. There is a tendency for the subject of a transitive verb (marked by the ergative case) to precede the object of the clause (marked by the absolutive case). There is likewise a tendency for the subject of an intransitive verb (marked by the absolutive case) to precede the verb. The subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a clause (both marked by the absolutive case) are usually found right before the verb. However, "this is [all] merely a tendency." [19]

Iñupiaq grammar also includes morphological passive, antipassive, causative and applicative.

Noun incorporation

Noun incorporation is a common phenomenon in Malimiutun Iñupiaq. The first type of noun incorporation is lexical compounding. Within this subset of noun incorporation, the noun, which represents an instrument, location, or patient in relation to the verb, is attached to the front of the verb stem, creating a new intransitive verb. The second type is manipulation of case. It is argued whether this form of noun incorporation is present as noun incorporation in Iñupiaq, or "semantically transitive noun incorporation"—since with this kind of noun incorporation the verb remains transitive. The noun phrase subjects are incorporated not syntactically into the verb but rather as objects marked by the instrumental case. The third type of incorporation, manipulation of discourse structure, is supported by Mithun (1984) and argued against by Lanz (2010). See Lanz's paper for further discussion.[19] The final type of incorporation is classificatory noun incorporation, whereby a "general [noun] is incorporated into the [verb], while a more specific [noun] narrows the scope".[19] With this type of incorporation, the external noun can take on external modifiers and, like the other incorporations, the verb becomes intransitive. See Nominal Morphology (Instrumental Case, Usage of Instrumental table, row four) on this page for an example.

Switch-references

Switch-references occur in dependent clauses only with third person subjects. The verb must be marked as reflexive if the third person subject of the dependent clause matches the subject of the main clause (more specifically matrix clause).[19] Compare:

| Iñupiaq | English | English | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaakkama niġiŋaruq. | [hungry- third person - reflexive - conditional] [eat- third person - indicative] | When he/she got hungry, he/she ate. | The verb in the matrix clause (to eat) refers to the same person because the verb in the dependent clause (To get hungry) is reflexive. Therefore, a single person got hungry and ate. |

| Kaaŋman niġiŋaruq. | [hungry- third person - non reflexive - conditional] [eat - third person - indicative] | When he/she got hungry, (someone else) ate. | The verb in the matrix clause (to eat) refers to a different singular person because the verb in the dependent clause (To get hungry) is non-reflexive. |

Text sample

This is a sample of the Iñupiaq language of the Kivalina variety from Kivalina Reader, published in 1975.

Aaŋŋaayiña aniñiqsuq Qikiqtami. Aasii iñuguġuni. Tikiġaġmi Kivaliñiġmiḷu. Tuvaaqatiniguni Aivayuamik. Qulit atautchimik qitunġivḷutik. Itchaksrat iñuuvlutiŋ. Iḷaŋat Qitunġaisa taamna Qiñuġana.

This is the English translation, from the same source:

Aaŋŋaayiña was born in Shishmaref. He grew up in Point Hope and Kivalina. He marries Aivayuaq. They had eleven children. Six of them are alive. One of the children is Qiñuġana.

Vocabulary comparison

The comparison of various vocabulary in four different dialects:

| North Slope Iñupiaq[24] | Northwest Alaska Iñupiaq[24] (Kobuk Malimiut) |

King Island Iñupiaq[25] | Qawiaraq dialect[26] | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atausiq | atausriq | atausiq | atauchiq | 1 |

| malġuk | malġuk | maġluuk | malġuk | 2 |

| piŋasut | piñasrut | piŋasut | piŋachut | 3 |

| sisamat | sisamat | sitamat | chitamat | 4 |

| tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | 5 |

| itchaksrat | itchaksrat | aġvinikłit | alvinilġit | 6 |

| tallimat malġuk | tallimat malġuk | tallimat maġluuk | mulġunilġit | 7 |

| tallimat piŋasut | tallimat piñasrut | tallimat piŋasut | piŋachuŋilgit | 8 |

| quliŋuġutaiḷaq | quliŋŋuutaiḷaq | qulinŋutailat | quluŋŋuġutailat | 9 |

| qulit | qulit | qulit | qulit | 10 |

| qulit atausiq | qulit atausriq | qulit atausiq | qulit atauchiq | 11 |

| akimiaġutaiḷaq | akimiaŋŋutaiḷaq | agimiaġutailaq | . | 14 |

| akimiaq | akimiaq | agimiaq | . | 15 |

| iñuiññaŋŋutaiḷaq | iñuiñaġutaiḷaq | inuinaġutailat | . | 19 |

| iñuiññaq | iñuiñaq | inuinnaq | . | 20 |

| iñuiññaq qulit | iñuiñaq qulit | inuinaq qulit | . | 30 |

| malġukipiaq | malġukipiaq | maġluutiviaq | . | 40 |

| tallimakipiaq | tallimakipiaq | tallimativiaq | . | 100 |

| kavluutit | . | kabluutit | . | 1000 |

| nanuq | nanuq | taġukaq | nanuq | polar bear |

| ilisaurri | ilisautri | iskuuqti | ilichausrirri | teacher |

| miŋuaqtuġvik | aglagvik | iskuuġvik | naaqiwik | school |

| aġnaq | aġnaq | aġnaq | aŋnaq | woman |

| aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | man |

| aġnaiyaaq | aġnauraq | niaqsaaġruk | niaqchiġruk | girl |

| aŋutaiyaaq | aŋugauraq | ilagaaġruk | ilagagruk | boy |

| Tanik | Naluaġmiu | Naluaġmiu | Naluaŋmiu | white person |

| ui | ui | ui | ui | husband |

| nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | wife |

| panik | panik | panik | panik | daughter |

| iġñiq | iġñiq | qituġnaq | . | son |

| iglu | tupiq | ini | ini | house |

| tupiq | palapkaaq | palatkaaq | tupiq | tent |

| qimmiq | qipmiq | qimugin | qimmuqti | dog |

| qavvik | qapvik | qappik | qaffik | wolverine |

| tuttu | tuttu | tuttu | tuttupiaq | caribou |

| tuttuvak | tiniikaq | tuttuvak, muusaq | . | moose |

| tulugaq | tulugaq | tiŋmiaġruaq | anaqtuyuuq | raven |

| ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | snowy owl |

| tatqiq | tatqiq | taqqiq | taqiq | moon/month |

| uvluġiaq | uvluġiaq | ubluġiaq | ubluġiaq | star |

| siqiñiq | siqiñiq | mazaq | matchaq | sun |

| niġġivik | tiivlu, niġġivik | tiivuq, niġġuik | niġġiwik | table |

| uqautitaun | uqaqsiun | qaniqsuun | qaniqchuun | telephone |

| mitchaaġvik | mirvik | mizrvik | mirrvik | airport |

| tiŋŋun | tiŋmisuun | silakuaqsuun | chilakuaqchuun | airplane |

| qai- | mauŋaq- | qai- | qai- | to come |

| pisuaq- | pisruk- | aġui- | aġui- | to walk |

| savak- | savak- | sawit- | chuli- | to work |

| nakuu- | nakuu- | naguu- | nakuu- | to be good |

| maŋaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | maŋaqtaaq, taaqtaaq | black |

| uvaŋa | uvaŋa | uaŋa | uwaŋa, waaŋa | I, me |

| ilviñ | ilvich | iblin | ilvit | you (singular) |

| kiña | kiña | kina | kina | who |

| sumi | nani, sumi | nani | chumi | where |

| qanuq | qanuq | qanuġuuq | . | how |

| qakugu | qakugu | qagun | . | when (future) |

| ii | ii | ii'ii | ii, i'i | yes |

| naumi | naagga | naumi | naumi | no |

| paniqtaq | paniqtaq | paniqtuq | pipchiraq | dried fish or meat |

| saiyu | saigu | saayuq | chaiyu | tea |

| kuuppiaq | kuukpiaq | kuupiaq | kupiaq | coffee |

Notes

See also

- Inuit languages

- Inuit-Yupik-Unangan languages

- Edna Ahgeak MacLean, a well-known Iñupiaq linguist

- Inupiat people

References

- ↑ "Population and Speaker Statistics" (in en-US). Alaska Native Language Center. https://www.uaf.edu/anlc/languages/pop.php.

- ↑ "Alaska OKs Bill Making Native Languages Official". https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2014/04/21/305688602/alaska-oks-bill-making-native-languages-official.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Alaskan Inupiaq". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/inup1234.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://uaf.edu/anlc/languages/stats/.

- ↑ "Inupiatun, North Alaskan". https://www.ethnologue.com/language/esi.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Alaska's indigenous languages now official along with English". Reuters. 2016-10-24. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-alaska-languages-idUSKCN0ID00E20141024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "SILEWP 1997-002". Sil.org. http://www.sil.org/silewp/1997/002/silewp1997-002.html. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "Inyupeat Language of the Arctic, 1970, Point Hope dialect". Language-archives.org. 2009-10-20. http://www.language-archives.org/item/oai:anla.uaf.edu:IN970W1970. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ Milan, Frederick A. (1959), The acculturation of the contemporary Eskimo of Wainwright Alaska, https://books.google.com/books?id=AdxGAAAAMAAJ&q=%2522inyupik%2522&dq=%2522inyupik%2522&source=bl&ots=1WLNiawgAO&sig=j7KvSlxD8SWxa7aT5jIb7m29Rtg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TtU2UKnlLKfN4QTrv4CICQ&ved=0CFMQ6AEwBw

- ↑ "Sheldon Jackson in Historical Perspective". http://www.alaskool.org/native_ed/articles/s_haycox/sheldon_jackson.htm.

- ↑ Krauss, Michael E. 1974. Alaska Native language legislation. International Journal of American Linguistics 40(2).150-52.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Iñupiaq/Inupiaq". languagegeek.com. http://www.languagegeek.com/inu/inupiaq.html. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 13.27 13.28 13.29 13.30 13.31 13.32 13.33 13.34 13.35 13.36 13.37 MacLean, Edna Ahgeak (1986). North Slope Iñupiaq Grammar: First Year. Alaska Native Language Center, College of Liberal Arts; University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ISBN 1-55500-026-6.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 Dorais, Louis-Jacques (2010). The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics, and Society in the Arctic. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 28. ISBN 978-0-7735-3646-3.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Burch 1980 Ernest S. Burch, Jr., Traditional Eskimo Societies in Northwest Alaska. Senri Ethnological Studies 4:253-304

- ↑ Spencer 1959 Robert F. Spencer, The North Alaskan Eskimo: A study in ecology and society, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 : 1-490

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Lowe, Ronald (1984). Uummarmiut Uqalungiha Mumikhitchiȓutingit: Basic Uummarmiut Eskimo Dictionary. Inuvik, Northwest Territories, Canada: Committee for Original Peoples Entitlement. pp. xix-xxii. ISBN 0-9691597-1-4.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Kaplan, Lawrence (1981). Phonological Issues In North Alaska Inupiaq. Alaska Native Language Center, University of Fairbanks. pp. 85. ISBN 0-933769-36-9.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 19.22 19.23 19.24 19.25 19.26 19.27 19.28 19.29 19.30 19.31 Lanz, Linda A. (2010). A grammar of Iñupiaq morphosyntax (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/62097.

- ↑ Kaplan, Larry (1981). North Slope Iñupiaq Literacy Manual. Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- ↑ Project Naming , the identification of Inuit portrayed in photographic collections at Library and Archives Canada

- ↑ Kaplan, Lawrence (2000). "L'Inupiaq et les contacts linguistiques en Alaska". In Tersis, Nicole and Michèle Therrien (eds.), Les langues eskaléoutes: Sibérie, Alaska, Canada, Groënland, pages 91-108. Paris: CNRS Éditions. For an overview of Inupiaq phonology, see pages 92-94.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Seiler, Wolf A. (2012). Iñupiatun Eskimo Dictionary. Sil Language and Culture Documentation and Descriptions. SIL International. pp. Appendix 7. http://www-01.sil.org/silepubs/Pubs/928474543482/Seiler_Inupiatun_Eskimo_Dictionary_LCDD_16.pdf.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Interactive IñupiaQ Dictionary". Alaskool.org. http://www.alaskool.org/language/dictionaries/inupiaq/default.htm. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "Ugiuvaŋmiuraaqtuaksrat / Future King Island Speakers". Ankn.uaf.edu. 2009-04-17. http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/curriculum/Masters_Projects/Yaayuk/Chap5.html. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ Agloinga, Roy (2013). Iġałuiŋmiutullu Qawairaġmiutullu Aglait Nalaunaitkataat. Atuun Publishing Company.

Print Resources: Existing Dictionaries, Grammar Books and Other

- Barnum, Francis. Grammatical Fundamentals of the Innuit Language As Spoken by the Eskimo of the Western Coast of Alaska. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1970.

- Blatchford, DJ. Just Like That!: Legends and Such, English to Inupiaq Alphabet. Kasilof, AK: Just Like That!, 2003. ISBN 0-9723303-1-3

- Bodfish, Emma, and David Baumgartner. Iñupiat Grammar. Utqiaġvigmi: Utqiaġvium minuaqtuġviata Iñupiatun savagvianni, 1979.

- Kaplan, Lawrence D. Phonological Issues in North Alaskan Inupiaq. Alaska Native Language Center research papers, no. 6. Fairbanks, Alaska (Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks 99701): Alaska Native Language Center, 1981.

- Kaplan, Lawrence. Iñupiaq Phrases and Conversations. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 2000. ISBN 1-55500-073-8

- MacLean, Edna Ahgeak. Iñupiallu Tanņiḷḷu Uqaluņisa Iḷaņich = Abridged Iñupiaq and English Dictionary. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1980.

- Lanz, Linda A. A Grammar of Iñupiaq Morphosyntax. Houston, Texas: Rice University, 2010.

- MacLean, Edna Ahgeak. Beginning North Slope Iñupiaq Grammar. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1979.

- Seiler, Wolf A. Iñupiatun Eskimo Dictionary. Kotzebue, Alaska: NANA Regional Corporation, 2005.

- Seiler, Wolf. The Modalis Case in Iñupiat: (Eskimo of North West Alaska). Giessener Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, Bd. 14. Grossen-Linden: Hoffmann, 1978. ISBN 3-88098-019-5

- Webster, Donald Humphry, and Wilfried Zibell. Iñupiat Eskimo Dictionary. 1970.

External links and language resources

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | Iñupiatun edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

There are a number of online resources that can provide a sense of the language and information for second language learners.

- Atchagat Pronunciation Video by Aqukkasuk

- Alaskool Inupiaq Language Resources

- Inupiaq Language on Alaskanativelanguages.com by Iyaġak[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Animal Names in Brevig Mission Dialect

- Atchagat App by the Grant and Reid Magdanz—Allows you to text using Inupiaq characters:

- Dictionary of Inupiaq, 1970 University of Fairbanks PDF by Webster

- Endangered Alaskan Language Goes Digital from National Public Radio

- Inupiaq Handbook for Teachers (A story of the Inupiaq language and further resources):

- North Slope Grammar Second Year by Dr. Edna MacLean PDF

- Online Iñupiaq morphological analyser

- Storybook—The Teller Reader, A Collection of Stories in the Brevig Mission Dialect --

- Storybook—Quliaqtuat Mumiaksrat by Alaska Native Language Program, UAF and Dr. Edna MacLean

- Qargi.com: an online community focused on supporting modern and triditional Iñupiaq life, language and culture, a Iñupiaq social networking site focused on education and founded under the leadership of the Iñupiaq Education Department, North Slope School District and with the community support of Uncivilized Films (Naninaaq Productions), Community Prophets, Katalyst Web Design, Ilisaunnat, Iñupiaq History, Language and Culture Commission, Ilisagvik College, and the Smithsonian Insititute.

- The dialects of Inupiaq- From Languagegeek.com, includes Northern Alaskan Consonants (US alphabet), Northern Alaskan Vowels, Seward Peninsula Consonants, Seward Peninsula Vowels

- InupiaqWords YouTube account

- https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/62097/3421210.PDF?sequence=1 — Linda A. Lanz's Grammar of Iñupiaq (Malimiutun) Morphosyntax. The majority of grammar introduced on this Wikipedia page is cited from this grammar. Lanz's explanations are very detailed and thorough—a great source for gaining a more in-depth understanding of Iñupiaq grammar.