Social:Nezak

Nezak Huns Nēzak šāh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 484–665 | |||||||||||||

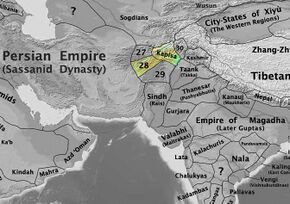

The Nezak kingdom in 565 CE | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Ghazna, Kapisa | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Pahlavi script (written)[1] Middle Persian (common)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Zoroastrianism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Nomadic empire | ||||||||||||

| Nezak Shah | |||||||||||||

• 6-7th century CE | Napki Malka | ||||||||||||

• 653 - 665 | Ghar-ilchi | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Established | 484 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 665 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Hunnic Drachm | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan Pakistan | ||||||||||||

The Nezak Huns, whose ruler was named in Middle Persian Nēzak šāh, were one of the four groups of Huna people in the area of the Hindu Kush. The Nezak kings, with their characteristic gold bull's-head crown, ruled from Ghazni and Kapisa. While their history is obscured, the Nezak's left significant coinage documenting their polity's prosperity. They are called Nezak because of the inscriptions on their coins, which often bear the mention "Nezak Shah". They were the last of the four major "Hunic" states known collectively as Xionites or "Hunas", their predecessors being, in chronological order, the Kidarites, the Hephthalites, and the Alchon.

The term 'Hun' may cause confusion. The word has three basic meanings: 1) the Huns proper, that is, Attila's people; 2) groups associated with the Huna people who invaded northern India; 3) a vague term for Hun-like people. Here the word has the second meaning with elements of the third.

Etymology

Maria Magdolna Tatár compares Nezak to nizāk, a minor royal title, of non-Turkic provenance,[2] borrowed and borne by Turks north of the Oxus, to the Western Turkic title 泥孰 níshú, in reconstructed Middle Chinese *niei-źiuk, and to Manichaean Uighur nïğošak "auditor", Sogdian nwgš’k, and Parthian n(y)gwš’g, nywš’g.[3] According to Gerard Clauson, the Uyghur title nïğošak "auditor" is of Iranian origin and means "hearer."[4] Meanwhile, János Harmatta connected *niźük to unattested Saka *näjsuka- "fighter, warrior" from *näjs- "to fight".[5] Frantz Grenet sees a possible, yet not firmly established connection with Middle Persian nēzag spear.[6]

History

The Nezak Huns established their realm in 484, after the defeat and death of the Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) Peroz I (r. 459–484) against the Hephthalites. With the weakening of Sasanian authority in the east, the Nezak Huns managed to take control of Zabulistan.[7] There they imitated their coins on the Sasanian imperial coins, while also adopting aspects from the neighbouring Alkhan coins. They portrayed themselves with the winged crown of Peroz.[7] From that point, the Nezaks consolidated their power in Zabulistan and in the 6th century expanded into Kabulistan, deposing the Alchon Huns from Kapisa.

Nezak coins with the bull's crown appear well into the 8th century,[8] at which time it appears that a confederacy emerges between the Nezaks and the Alchons, possibly against Turkic invaders.[9]

Alchon retreat from India

Around the middle of the 6th century CE, the Alchons, after having extensively invaded the heartland of India, had withdrawn from Kashmir, Punjab and Gandhara, and going back west across the Khyber pass they resettled in Kabulistan. There, their coinage suggests that they merged with the Nezak Huns.[10]

Eventually, the Nezak-Alchons were replaced by the Turk shahi dynasty,[9] first in Zabulistan and then in Kabulistan. The last Nezak king known by name was Ghar-ilchi, who was confirmed by the Chinese emperor. Between 661 and 665, Chinese and Arab sources indicate that a new Turkic ruler became Shah of Kabul.[11] Having lost Ghazni and Kabul, the Nezak dynasty declined rapidly as indicated by the progressive elimination of Nezak symbols from the historical coin record.

Main rulers

- Napki Malka (Gandhara, c. 475–576).

- Shri Shahi, circa 560-620 CE.

- Ghar-ilchi, 653-665

Coinage

-

Nezak Huns Anonymous ("Nezak Shah") circa 500–560.

-

Coin minted in Ghazni

-

Billon drachm

-

Bronze drachm

-

Nezak king Napki Malka

-

Nezak Huns ruler Sahi Tigin (?) Early 8th century CE.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rezakhani 2017, p. 159.

- ↑ Inaba, M. "Nezak in Chinese Sources?" Coins, Art and Chronology II. Ed. M. Alram et.al. (2010) p. 191-202

- ↑ Tatár, M. M. (2005) "Some Central Asian Ethnonyms Among the Mongols" Bolor-un gerel. Crystal-splendor. Tanulmányok Kara György tiszteletére. I-II. Budapest. p. 3-4

- ↑ Clauson, G. An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-13th Century Turkish (1972). p. 774

- ↑ Inaba, M. "Nezak in Chinese Sources?" Coins, Art and Chronology II. Ed. M. Alram et.al. (2010) p. 191

- ↑ Grenet 2002, p. 159.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alram 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Robert Göbl (1967). Dokumente zur Geschichte der iranischen Hunnen in Baktrien und Indien. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. GGKEY:4TALPN86ZJB. https://books.google.com/books?id=5lpNHxfbKIEC.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Klaus Vondrovec (2014). Coinage of the Iranian Huns and Their Successors from Bactria to Gandhara (4th to 8th Century CE). ISBN 978-3-7001-7695-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ek6_jgEACAAJ.

- ↑ Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

- ↑ "13. The Turk Shahis in Kabulistan". http://pro.geo.univie.ac.at/projects/khm/showcases/showcase13?language=en.

Sources

- Alram, Michael (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle 174: 261–291. (registration required)

- Grenet, Frantz (2002). "Nēzak". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nezak.

- Payne, Richard (2016). "The Making of Turan: The Fall and Transformation of the Iranian East in Late Antiquity". Journal of Late Antiquity (Johns Hopkins University Press) 9: 4–41. doi:10.1353/jla.2016.0011.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. https://books.google.com/books?id=bjRWDwAAQBAJ&q=false.