Social:Old Spanish

| Old Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Old Castilian | |

| roman, romançe, romaz | |

| Pronunciation | [roˈman] |

| Native to | Crown of Castile |

| Region | Iberian peninsula |

| Ethnicity | Castilians, later Spaniards |

| Era | 9th–15th centuries |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Latin Aljamiado (marginal) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | osp |

osp | |

| Glottolog | olds1249[2] |

Old Spanish, also known as Old Castilian (Spanish: castellano antiguo; Template:Lang-osp[3] [roˈman], romançe,[3] romaz[3]), or Medieval Spanish (Spanish: español medieval), was originally a dialect of Vulgar Latin spoken in the former provinces of the Roman Empire that provided the root for the early form of the Spanish language that was spoken on the Iberian Peninsula from the 9th century until roughly the beginning of the 15th century, before a series of consonant shifts gave rise to modern Spanish. The poem Cantar de Mio Cid ('The Poem of the Cid'), published around 1200, is the best known and most extensive work of literature in Old Spanish.

Phonology

The phonological system of Old Spanish was quite similar to that of other medieval Romance languages.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| laminal | apical | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Stop/Affricate | voiceless | p | t̪ | t͡s̻ ~ s̻ | t͡ʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d̪ | d͡z̻ ~ z̻ | d͡ʒ ~ ʒ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | ɸ | s̺ | ʃ | |||

| voiced | β | z̺ | |||||

| Approximant | ʝ ~ j | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | |||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Sibilants

Among the consonants, there were seven sibilants, including three voiceless/voiced pairs:

- Alveolar:

- Apicoalveolar:

- Postalveolar:

The set of sounds is identical to that found in medieval Portuguese and almost the same as the system present in the modern Mirandese language.

The Modern Spanish system evolved from the Old Spanish one with the following changes:

- The affricates /t͡s̻/ and /d͡z̻/ were simplified to laminodental fricatives /s̻/ and /z̻/, which remained distinct from the apicoalveolar sounds /s̺/ and /z̺/ (a distinction also present in Basque). The affricate [d͡ʒ] fell out of use as a positional variant of the fricative /ʒ/.

- The voiced sibilants then all lost their voicing and so merged with the voiceless ones. (Voicing remains before voiced consonants, such as mismo, desde, and rasgo, but only allophonically.)

- The merged /ʃ/ was retracted to /x/.

- The merged /s̻/ was drawn forward to /θ/. In some parts of Andalusia and the Canary Islands, however (and so then in Latin America), the merged /s̺/ was instead drawn forward, merging into /s̻/.

Changes 2–4 all occurred in a short period of time, around 1550–1600. The change from /ʃ/ to /x/ is comparable to the fluctuation occurring in the sj-sound of Modern Swedish.

The Old Spanish spelling of the sibilants was identical to modern Portuguese spelling, which, unlike Spanish, still preserves most of the sounds of the medieval language, and so is still a mostly faithful representation of the spoken language. Examples of words before spelling was altered in 1815 to reflect the changed pronunciation:[4]

- passar 'to pass' versus casar 'to marry' (Modern Spanish pasar, casar, cf. Portuguese passar, casar)

- osso 'bear' versus oso 'I dare' (Modern Spanish oso in both cases, cf. Portuguese urso [a borrowing from Latin], ouso)

- foces 'sickles' versus fozes 'base levels' (Modern Spanish hoces in both cases, cf. Portuguese foices, fozes)

- coxo 'lame' versus cojo 'I seize' (Modern Spanish cojo in both cases, cf. Portuguese coxo, colho)

- xefe 'chief' (Modern Spanish jefe, cf. Portuguese chefe)

- Xerez (Modern Spanish Jerez, cf. Portuguese Xeres)

- oxalá 'if only' (Modern Spanish ojalá, cf. Portuguese oxalá)

- dexar 'leave' (Modern Spanish dejar, cf. Portuguese deixar)

- roxo 'red' (Modern Spanish rojo, cf., Portuguese roxo 'purple')

- fazer or facer 'make' (Modern Spanish hacer, cf. Portuguese fazer)

- dezir 'say' (Modern Spanish decir, cf. Portuguese dizer)

- lança 'lance' (Modern Spanish lanza, cf. Portuguese lança)

The Old Spanish origins of jeque and jerife reflect their Arabic origins, xeque from Arabic sheikh and xerife from Arabic sharif.

Bilabial consonants

Voiced

The voiced bilabial stop and fricative were still distinct sounds in early Old Spanish, judging by the consistency with which they were spelled as ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩ respectively. (/b/ derived from Latin word-initial /b/ or intervocalic /p/, while /β/ derived from Latin /w/ or intervocalic /b/.) Nevertheless, the two sounds could be confused in consonant clusters (cf. alba~alva 'dawn') or in word-initial position, perhaps after /n/ or a pause. The two appear to have merged in word-initial position by about 1400 CE and in all other environments by the mid–late 16th century at the latest. In Modern Spanish, many earlier instances of ⟨b⟩ were replaced with ⟨v⟩, or vice versa, to conform to Latin spelling.[5]

Voiceless

At an archaic stage, there would have existed three allophones of /f/ in approximately the following distribution:[6]

- [ɸ] before non-back vowels, [j], [ɾ] or [l]

- [h] before the back vowels [o] and [u]

- [ʍ] or [hɸ] before [w]

By the early stages of Old Spanish, the allophone [h][lower-alpha 1] had spread to all prevocalic environments and possibly before [j] as well.[7]

Subsequently, the bilabial allophones of /f/ (that is, those other than [h]) were modified to the labiodental [f] in 'proper' speech, likely under the influence of the many French and Occitan speakers who migrated to Spain from the twelfth century onward, bringing with them their reformed Latin pronunciation.[8] This had the effect of introducing into Old Spanish numerous borrowings beginning with a labiodental [f]. The result was a phonemic split of /f/ into /f/ and /h/, since e.g. the native [ˈhoɾma] 'last' was now distinct from the borrowed [ˈfoɾma] 'form' (both ultimately derived from the Latin forma).[9] Compare also the native [ˈhaβla] 'speech' and borrowed [ˈfaβula] 'fable'. In some cases, doublets appear in apparently native vocabulary, possibly the result of borrowings from other Ibero-Romance varieties; compare modern hierro 'iron' and fierro 'branding iron' or the names Hernando and Fernando.

⟨ch⟩

Old Spanish had ⟨ch⟩, just as Modern Spanish does, which mostly represents a development of earlier */jt/ (still preserved in Portuguese and French), from the Latin ⟨ct⟩. The use of ⟨ch⟩ for /t͡ʃ/ originated in Old French and spread to Spanish, Portuguese, and English despite the different origins of the sound in each language:

- mucho 'much', from earlier muito (Latin multum, cf. Portuguese muito, French moult (rare, regional))

- noche 'night', from earlier noite (Latin noctem, cf. Portuguese noite, French nuit)

- ocho 'eight', from earlier oito (Latin octō, cf. Portuguese oito, French huit)

- hecho 'made' or 'fact', from earlier feito (Latin factum, cf. Portuguese feito, French fait)

Orthography

Writing systems

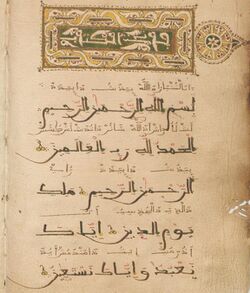

Old Spanish was generally written with some variation of the Latin script. In addition, the Arabic script was used by crypto-Muslims for certain writings in dialectal Spanish or Aragonese in a writing system called Aljamiado.[11]

Spelling

Palatal nasal and lateral

The palatal nasal /ɲ/ was written ⟨nn⟩ (the geminate nn being one of the sound's Latin origins), but it was often abbreviated to ⟨ñ⟩ following the common scribal shorthand of replacing an ⟨m⟩ or ⟨n⟩ with a tilde above the previous letter. Later, ⟨ñ⟩ was used exclusively, and it came to be considered a letter in its own right by Modern Spanish. Also, as in modern times, the palatal lateral /ʎ/ was indicated with ⟨ll⟩, again reflecting its origin from a Latin geminate.

Greek digraphs

The Graeco-Latin digraphs (digraphs in words of Greek-Latin origin) ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨(r)rh⟩ and ⟨th⟩ were reduced to ⟨c⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨(r)r⟩ and ⟨t⟩, respectively:

- christiano (Modern Spanish cristiano)

- triumpho (Modern Spanish triunfo)

- myrrha (Modern Spanish mirra)

- theatro (Modern Spanish teatro)

Word-initial Y to I

Word-initial [i] was spelled ⟨Y⟩, which was simplified to ⟨I⟩.

Morphology

In Old Spanish, perfect constructions of movement verbs, such as ir ('(to) go') and venir ('(to) come'), were formed using the auxiliary verb ser ('(to) be'), as in Italian and French: Las mugieres son llegadas a Castiella was used instead of Las mujeres han llegado a Castilla ('The women have arrived in Castilla').

Possession was expressed with the verb aver (Modern Spanish haber, '(to) have'), rather than tener: Pedro ha dos fijas was used instead of Pedro tiene dos hijas ('Pedro has two daughters').

In the perfect tenses, the past participle often agreed with the gender and number of the direct object: María ha cantadas dos canciones was used instead of Modern Spanish María ha cantado dos canciones ('María has sung two songs'). However, that was inconsistent even in the earliest texts.

The prospective aspect was formed with the verb ir ('(to) go') along with the verb in infinitive, with the difference that in Modern Spanish it's included the preposition a:

- Al Çid beso la mano, la senna ua tomar. (Cantar de mio Cid, 691)

- Al Cid besó la mano, la enseña va a tomar. (Modern Spanish equivalent)

Personal pronouns and substantives were placed after the verb in any tense or mood unless a stressed word was before the verb.[example needed]

The future and the conditional tenses were not yet fully grammaticalised as inflections; rather, they were still periphrastic formations of the verb aver in the present or imperfect indicative followed by the infinitive of a main verb.[12] Pronouns, therefore, by the general placement rules, could be inserted between the main verb and the auxiliary in these periphrastic tenses, as still occurs with Portuguese (mesoclisis):

- E dixo: ― Tornar-m-é a Jherusalem. (Fazienda de Ultra Mar, 194)

- Y dijo: ― Me tornaré a Jerusalén. (literal translation into Modern Spanish)

- E disse: ― Tornar-me-ei a Jerusalém. (literal translation into Portuguese)

- And he said: "I will return to Jerusalem." (English translation)

- En pennar gelo he por lo que fuere guisado (Cantar de mio Cid, 92)

- Se lo empeñaré por lo que sea razonable (Modern Spanish equivalent)

- Penhorá-lho-ei pelo que for razoável (Portuguese equivalent)

- I will pawn them it for whatever it be reasonable (English translation)

When there was a stressed word before the verb, the pronouns would go before the verb: non gelo empeñar he por lo que fuere guisado.

Generally, an unstressed pronoun and a verb in simple sentences combined into one word.[clarification needed] In a compound sentence, the pronoun was found in the beginning of the clause: la manol va besar = la mano le va a besar.[citation needed]

The future subjunctive was in common use (fuere in the second example above) but it is generally now found only in legal or solemn discourse and in the spoken language in some dialects, particularly in areas of Venezuela, to replace the imperfect subjunctive.[13] It was used similarly to its Modern Portuguese counterpart, in place of the modern present subjunctive in a subordinate clause after si, cuando etc., when an event in the future is referenced:

- Si vos assi lo fizieredes e la ventura me fuere complida

- Mando al vuestro altar buenas donas e Ricas (Cantar de mio Cid, 223–224)

- Si vosotros así lo hiciereis y la ventura me fuere cumplida,

- Mando a vuestro altar ofrendas buenas y ricas (Modern Spanish equivalent)

- Se vós assim o fizerdes e a ventura me for comprida,

- Mando a vosso altar oferendas boas e ricas. (Portuguese equivalent; 'ventura' is an obsolete word for 'luck'.)

- If you do so and fortune is favourable toward me,

- I will send to your altar fine and rich offerings (English translation)

Vocabulary

| Latin | Old Spanish | Modern Spanish | Modern Portuguese |

|---|---|---|---|

| acceptare, captare, effectum, respectum | acetar, catar, efeto, respeto | aceptar, captar, efecto, respecto, respeto | aceitar, captar, efeito, respeito |

| et, non, nos, hic | e, et; non, no; nós; í | y, e; no; nosotros; ahí | e; não; nós; aí |

| stabat; habui, habebat; facere, fecisti | estava; ove, avié; far/fer/fazer, fezist(e)/fizist(e) | estaba; hube, había; hacer, hiciste | estava; houve, havia; fazer, fizeste |

| hominem, mulier, infantem | omne/omre/ombre, mugier/muger, ifante | hombre, mujer, infante | homem, mulher, infante |

| cras, mane (maneana); numquam | cras, man, mañana; nunqua/nunquas | mañana, nunca | manhã, nunca |

| quando, quid, qui (quem), quo modo | quando, que, qui, commo/cuemo | cuando, que, quien, como | quando, que, quem, como |

| fīlia | fyia, fija | hija | filha |

Sample text

The following is a sample from Cantar de Mio Cid (lines 330–365), with abbreviations resolved, punctuation (the original has none), and some modernized letters.[14] Below is the original Old Spanish text in the first column, along with the same text in Modern Spanish in the second column and an English translation in the third column.

The poem

Ya sennor glorioso, padre que en çielo estas,

Fezist çielo e tierra, el terçero el mar,

Fezist estrelas e luna, e el sol pora escalentar,

Prisist en carnaçion en sancta maria madre,

En belleem apareçist, commo fue tu veluntad,

Pastores te glorificaron, ovieron de a laudare,

Tres Reyes de arabia te vinieron adorar,

Melchior e gaspar e baltasar, oro e tus e mirra

Te offreçieron, commo fue tu veluntad.

Saluest a jonas quando cayo en la mar,

Saluest a daniel con los leones en la mala carçel,

Saluest dentro en Roma al sennor san sabastián,

Saluest a sancta susanna del falso criminal,

Por tierra andidiste xxxii annos, sennor spirital,

Mostrando los miraculos, por en auemos que fablar,

Del agua fezist vino e dela piedra pan,

Resuçitest a Lazaro, ca fue tu voluntad,

Alos judios te dexeste prender, do dizen monte caluarie

Pusieron te en cruz, por nombre en golgota,

Dos ladrones contigo, estos de sennas partes,

El vno es en parayso, ca el otro non entro ala,

Estando en la cruz vertud fezist muy grant,

Longinos era çiego, que nuquas vio alguandre,

Diot con la lança enel costado, dont yxio la sangre,

Corrio la sangre por el astil ayuso, las manos se ouo de vntar,

Alçolas arriba, legolas a la faz,

Abrio sos oios, cato atodas partes,

En ti crouo al ora, por end es saluo de mal.

Enel monumento Resuçitest e fust alos ynfiernos,

Commo fue tu voluntad,

Quebranteste las puertas e saqueste los padres sanctos.

Tueres Rey delos Reyes e de todel mundo padre,

Ati adoro e creo de toda voluntad,

E Ruego a san peydro que me aiude a Rogar

Por mio çid el campeador, que dios le curie de mal,

Quando oy nos partimos, en vida nos faz iuntar.

Oh Señor glorioso, Padre que en el cielo estás,

Hiciste el cielo y la tierra, al tercer día el mar,

Hiciste las estrellas y la luna, y el sol para calentar,

Te encarnaste en Santa María madre,

En Belén apareciste, como fue tu voluntad,

Pastores te glorificaron, te tuvieron que loar,

Tres reyes de Arabia te vinieron a adorar,

Melchor, Gaspar y Baltasar; oro, incienso y mirra

Te ofrecieron, como fue tu voluntad.

Salvaste a Jonás cuando cayó en el mar,

Salvaste a Daniel con los leones en la mala cárcel,

Salvaste dentro de Roma al señor San Sebastián,

Salvaste a Santa Susana del falso criminal,

Por tierra anduviste treinta y dos años, Señor espiritual,

Mostrando los milagros, por ende tenemos qué hablar,

Del agua hiciste vino y de la piedra pan,

Resucitaste a Lázaro, porque fue tu voluntad,

Por los judíos te dejaste prender, en donde llaman Monte Calvario

Te pusieron en la cruz, en un lugar llamado Golgotá,

Dos ladrones contigo, estos de sendas partes,

Uno está en el paraíso, porque el otro no entró allá,

Estando en la cruz hiciste una virtud muy grande,

Longinos era ciego que jamás se vio,

Te dio con la lanza en el costado, de donde salió la sangre,

Corrió la sangre por el astil abajo, las manos se tuvo que untar,

Las alzó arriba, se las llevó a la cara,

Abrió sus ojos, miró a todas partes,

En ti creyó entonces, por ende se salvó del mal.

En el monumento resucitaste y fuiste a los infiernos,

Como fue tu voluntad,

Quebrantaste las puertas y sacaste a los padres santos.

Tú eres Rey de los reyes y de todo el mundo padre,

A ti te adoro y en ti creo de toda voluntad,

Y ruego a San Pedro que me ayude a rogar

Por mi Cid el Campeador, que Dios le cuide del mal,

Cuando hoy partamos, en vida haznos juntar.

English translation

O glorious Lord, Father who art in Heaven,

Thou madest Heaven and Earth, and on the third day the sea,

Thou madest the stars and the Moon, and the Sun for warmth,

Thou incarnatedst Thyself of the Blessed Mother Mary,

In Bethlehem Thou appearedst, for it was Thy will,

Shepherds glorified Thee, they gave Thee praise,

Three kings of Arabia came to worship Thee,

Melchior, Caspar, and Balthazar; offered Thee

Gold, frankincense, and myrrh, for it was Thy will.

Thou savedst Jonah when he fell into the sea,

Thou savedst Daniel from the lions in the terrible jail,

Thou savedst Saint Sebastian in Rome,

Thou savedst Saint Susan from the false charge,

On Earth Thou walkedst thirty-two years, Spiritual Lord,

Performing miracles, thus we have of which to speak,

Of the water Thou madest wine and of the stone bread,

Thou revivedst Lazarus, because it was Thy will,

Thou leftest Thyself to be arrested by the Jews, where they call Mount Calvary,

They placed Thee on the Cross, in the place called Golgotha,

Two thieves with Thee, these of split paths,

One is in Paradise, but the other did not enter there,

Being on the Cross Thou didst a very great virtue,

Longinus was blind ever he saw Thee,

He gave Thee a blow with the lance in the broadside, where he left the blood,

Running down the arm, the hands Thou hadst spread,

Raised it up, as it led to Thy face,

Opened their eyes, saw all parts,

And believed in Thee then, thus saved them from evil.

Thou revivedst in the tomb and went to Hell,

For it was Thy will,

Thou hast broken the doors and brought out the holy fathers.

Thou art King of Kings and of all the world Father,

I worship Thee and I believe in all Thy will,

And I pray to Saint Peter to help with my prayer,

For my Cid the Champion, that God nurse from evil,

When we part today, that we are joined in this life or the next.

See also

- History of the Spanish language

- Early Modern Spanish (Middle Spanish)

- Judeo-Spanish preserves some of the sounds and terms of Old Spanish that have been lost in Modern Spanish.

Notes

- ↑ Originally the result of dissimilation, via delabialization, of [ɸ] before the rounded ('labial') vowels [o] and [u].

References

- ↑ Eberhard, Simons & Fennig (2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin et al., eds (2022). "Castilic". Glottolog 4.6. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/cast1243. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Glottolog" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Boggs, Ralph Steele (1946). "roman" (in en). Tentative Dictionary of Medieval Spanish. the compilers. p. 446-447. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Tentative_Dictionary_of_Medieval_Spanish/jsoKAQAAMAAJ?gbpv=1&pg=PA446&printsec=frontcover&dq=romaz. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ Ortografía de la lengua castellana – Real Academia Española –. Imprenta real. 1815. https://archive.org/details/ortografadelale03espagoog. Retrieved 2015-05-22. "ortografía 1815."

- ↑ Penny 2002: §2.6.1. This citation covers the preceding paragraph.

- ↑ Lloyd 1987: 214–215; Penny 2002: 92

- ↑ Per Penny (2002: 92). Lloyd (1987: 215–216, 322–323) broadly agrees, except on the matter of [h] spreading before [j].

- ↑ Penny 2002: 92; Lloyd 1987: 324

- ↑ Penny 2002: §2.6.4

- ↑ Martínez-de-Castilla-Muñoz, Nuria (2014-12-30). "The Copyists and their Texts. The Morisco Translations of the Qur’ān in the Tomás Navarro Tomás Library (CSIC, Madrid)". Al-Qanṭara 35 (2): 493–525. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2014.017. ISSN 1988-2955. http://al-qantara.revistas.csic.es/index.php/al-qantara/article/view/332/324.

- ↑ de Castilla, Nuria (2020-01-20). "Les emplois linguistiques et culturels derrière les textes aljamiados". Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 8 (1): 128–162. doi:10.1163/2212943X-00702013. ISSN 2212-9421. https://brill.com/view/journals/ihiw/8/1/article-p128_6.xml.

- ↑ A History of the Spanish Language. Ralph Penny. Cambridge University Press. Pag. 210.

- ↑ Diccionario de dudas y dificultades de la lengua española. Seco, Manuel. Espasa-Calpe. 2002. Pp. 222–3.

- ↑ A recording with reconstructed mediaeval pronunciation can be accessed here, reconstructed according to contemporary phonetics (by Jabier Elorrieta).

Bibliography

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2020). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (23rd ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com. Retrieved 22 June 2002.

- Lloyd, Paul M. 1987. From Latin to Spanish. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Penny, Ralph. 2002. A history of the Spanish language. Cambridge University Press.

External links

|