Social:Proto-Cuneiform

| Proto-Cuneiform | |

|---|---|

Kish Tablet | |

| Type | Ideographs

|

| Languages | Unknown but Sumerian likely |

| Created | c. 3300 BC |

Time period | c. 3300 BC to c. 2900 BC |

Child systems | Cuneiform |

The Proto-Cuneiform script was used in Mesopotamia from roughly 3300 BC to 2900 BC. It arose from the token based system used in the region for the preceding millennia and was replaced by the development of early Cuneiform script in the Early Dynastic I period. While the underlying language of Cuneiform is definitively Sumerian, the language base for Proto-Cuneiform is as yet uncertain.

History

Beginning around the 9th millennium BC a token based system came into use in various parts of the ancient Near East. These evolved into marked tokens and later marked envelopes, often called clay bullae.[1] It is usually assumed that these were the basis for the development of Proto-Cuneiform.[2][3]

Proto-Cuneiform emerged in the Uruk IV period, circa 3300 BC and continued through the Uruk III times. The script slowly evolved over time with signs changing and merging.[4] It was initially used in Uruk, later spreading to a few additional sites like Jemdet Nasr.[5]

Finally, in the Early Dynastic I (c. 2900 BC) period the standard Cuneiform script, in the Sumerian language, emerged though only about 400 tablets have yet been recovered from this period, mainly from Ur with a few from Uruk.[6]

Language

There is a longstanding debate in the academic community on when Sumerians came to Mesopotamia. This is partly driven by various linguistic arguments but also because a number of fundamental changes occurred in Mesopotamia, such as the plano-convex brick, at the same time as the Sumerian language definitively appeared in ED I. There are no clear clues in Proto-Cuneiform which has not prevented much speculation about the underlying language. Different languages have been proposed though often Sumerian is assumed.[7][8]

Corpus

About 170 similar tablets from Uruk V (circa 3500 BC) Susa and a few other sites in Iran like Tepe Sialk are considered as pre-proto-Elamite though with similarities to Proto-Cuneiform.[9] Sign lists and transliterations are less clear for this category.[10]

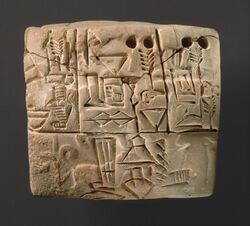

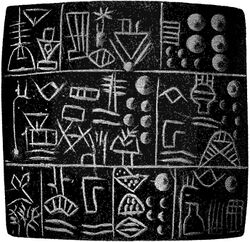

The vast majority of Proto-Cuneiform texts, about 4000, have been found at archaic Uruk, though in secondary contexts in the Eanna district. The tablets fall primarily into two styles, an earlier (building level IV) set with more naturalistic figures and written with a pointed stylus, and a later (building level III) in a more abstract style using a blunt stylus. These correspond to the Late Uruk (c. 3100 BC) and Jemdet Nasr (c. 3000 BC) periods.[11][12] Many had been used as fill for the foundation in the Eanna temple complex.[13] The findspots and analysis of sealing has led to suggestions that the tablets originated elsewhere and ended up at Uruk, where they were discarded.[14]

A smaller number of tablets were found in Jemdet Nasr, Khafajah and Tell Uqair. They tend to be less fragmentary and are sometimes found in stratified contexts. Some tablets have also made their way into various private and public collections.[15][16] For example, in 1988 82 complete well-preserved tablets from the Swiss Erlenmeyer Collection in Basel were auctioned off with most ending up in public collections.[17]

Some tablets had been sealed using a cylinder seal.[18]

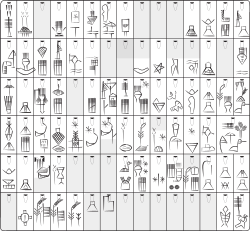

State of decipherment

Currently there are about 2000 known Proto-Cuneiform signs of which about 350 are numerical, 1100 are individual ideographic and 600 are complex (combination of 2 or more individual signs) signs.[19]

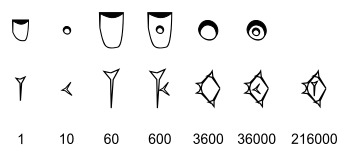

Numbers

The underlying basis of the proto-cuneiform, like the later cuneiform, is sexagesimal (base 60). Earlier researchers believed that this system rose out of an earlier decimal (base 10) substratum but that idea has now lost currency.[20]

"To achieve this goal is not an easy task, since there are about sixty different number signs appearing in the proto-cuneiform texts, and since many of these number signs have different values depending on context. Yet, the establishment of the various values of nearly all the proto-cuneiform number signs has now been achieved."[21]

Different products use different measurement systems and this can change with the context. In a single tablet the (Bisexagesimal System B) could be used for grain rations, (ŠE system Š) could be used for barley, and (ŠE system Š") be used for emmer wheat.[22]

Text

The largest group of proto-cuneiform texts (about 2000 from the Uruk IV period and about 3600 from the Uruk III period) are accounts ie "economic records".[23] They involve a variety of items including people, livestock, and grain. Unfortunately there are often multiple ways to do things. For example people can be listed two different ways 1) By gender and age (adult, minor, baby) or 2) without gender and in one of a number of age groups (0-1, 3-10 etc).[24]

Another large category (around a dozen in Uruk IV and about 750 for Uruk III)) are called "lexical lists" started appearing in Uruk IV but became much more common in Uruk III times. These are list of all metals or a list of all tools or all cities etc.[25][26][27][28] The genre persisted into Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian times.[29]

Publication

The proto-cuneiform texts from Uruk were published in a series of books (ATU)

- ATU 1. [5]Adam Falkenstein, "Archaische Texte aus Uruk", Berlin und Leipzig: Deutsche Forschungsgemein-schaft, Kommissionsverlag Otto Harrassowitz. 1936.

- ATU 2. [6]M. W. Green und Hans J. Nissen, unter Mitarbeit von Peter Damerow und Robert K. Englund, "Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk", Berlin 1987.

- ATU 3. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von Peter Damerow, "Die Lexikalischen Listen der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk", Berlin 1993.

- ATU 4. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen, "Katalog der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk"

- ATU 5. Robert K. Englund unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaic Administrative Texts from Uruk: The Early Campaigns", Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag 1994

- ATU 6. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaische Verwaltungstexte aus Uruk: Vorderasiatisches Museum II", Berlin 2005.

- ATU 7. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaische Verwaltungstexte aus Uruk: Die Heidelberger Sammlung", Berlin 2001.

And from other sites (MSVO)

- MSVO 1. Robert K. Englund, Jean-Pierre Grégoire, and Roger J. Matthews, "The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Jemdet Nasr I: Copies, Transliterations and Glossary", Materialien zu den frühen Schriftzeugnissen des Vorderen Orients Bd. 1. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1991

- MSVO 2. Matthews, R. J, "Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur", Berlin: Gebr. Mann 1993

- MSVO 3. Damerow, P. & Englund, R. K. forthcoming. "The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from the Erlenmeyer Collection" Berlin.

- MSVO 4. Robert K. Englund and Roger J. Matthews, "Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Diverse Collections", Materialien zu den frühen Schriftzeugnissen des Vorderen Orients Bd. 4. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1996

Gallery

-

Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.583

-

Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.602

-

Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.606

-

Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.564

-

Louvre Uruk III tablette écriture précunéiforme AO19936

-

Precuneiforme tablet-AO 8856-IMG 9155-gradient

-

Tablette precuneiforme AO 2753

-

Clay Tablet - Louvre - AO29562

-

Clay Tablet - Louvre - AO29560

-

Five day ration list - Jemdet Nasr

-

Numerical and proto cuneiforms tablets - Oriental Institute

-

Clay tablet, lexical text, listing 58 different terms for pig. From Uruk, Iraq. 3200 BCE. Pergamon Museum

-

Uruk period administrative tablet

-

Tontäfelchen Mesopotamien 3200vChr 2

-

Tablette numerale Sialk IV

See also

- Proto-Elamite

- Blau Monuments

References

- ↑ Overmann, Karenleigh A., "The Neolithic Clay Tokens", in The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 157-178, 2019

- ↑ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, "An Archaic Recording System and the Origin of Writing", Syro Mesopotamian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 1977

- ↑ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, "An Archaic Recording System in the Uruk-Jemdet Nasr Period", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 19–48, (Jan. 1979)

- ↑ Green, M. W., "Archaic Uruk Cuneiform", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 464–66, 1986

- ↑ Glassner, Jean-Jacques, "Writing in Sumer: The Invention of Cuneiform", Translated by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van de Mieroop. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003

- ↑ Lecompte, Camille, "Observations on Diplomatics, Tablet Layout and Cultural Evolution of the Early Third Millennium: The Archaic Texts from Ur", in Materiality of Writing in Early Mesopotamia, edited by Thomas E. Balke and Christina Tsouparopoulou, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 133-164, 2016

- ↑ Monaco, Salvatore F., "Proto-Cuneiform And Sumerians", Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, vol. 87, no. 1/4, pp. 277–82, 2014

- ↑ Monaco, Salvatore F., "Loan and Interest in the Archaic Texts", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 102, no. 2, pp. 165-178, 2013

- ↑ Dittman, R., "Seals, Sealings and Tablets. Thoughts on the changing pattern of administrative control from the Late-Uruk to the Proto-Elamite period at Susa", pp. 332–66 in Gamdat Nasr. Period or Re-gional Style? ed. U. Finkbeiner and R. Röllig. TAVO B/62. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1986

- ↑ Overmann, Karenleigh A., "Numerical Notations And Writing", in The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 179-206, 2019

- ↑ Nissen, Hans J., "The Archaic Texts from Uruk", World Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 317–34, 1986

- ↑ H.J. Nissen, "The Development of Writing and of Glyptic Art", in: U. Finkbeiner - W. Röllig (edd.): Gamdat Nasr — Period or Regional Style? Papers given at a symposium held in Tübingen, November 1983, Wiesbaden, pp. 316-331, 1986

- ↑ Stratford, Edward, "Archives and the Deformation of Time", Volume 1 A Year of Vengeance, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 316-332, 2017

- ↑ Charvát, Petr., "Early Texts and Sealings: 'Divine Journeys' in the Uruk IV Period?", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 30-33, 1995

- ↑ [1]Robert K. Englund, "Archaic Dairy Metrology", Iraq 53, pp. 101-104, 1991

- ↑ Falkenstein, Adam, "Archaische texte des Iraq-Museums in Baghdad", Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 40/7, pp. 401–410, 1937

- ↑ [2]Robert K. Englund, "Grain Accounting Practices in Archaic Mesopotamia", in: J. Høyrup and Peter Damerow, eds., Changing Views on Ancient Near Eastern Mathematics, BBVO 19; Berlin, 1-35, 2001

- ↑ Goff, Beatrice L., and Briggs Buchanan, "A Tablet of the Uruk Period in the Goucher College Collection", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 231–35, 1956

- ↑ [3]Anshuman Pandey, "Preliminary proposal to encode ProtoCuneiform in Unicode", L2/20193, September 21, 2020

- ↑ Powell, Marvin A. Jr., "Sumerian Area Measures and the Alleged Decimal Substratum", vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 165-221, 1972

- ↑ Friberg, Jöran, "Counting and Accounting in the Proto-Literate Middle East: Examples from Two New Volumes of Proto-Cuneiform Texts", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 51, pp. 107–37, 1999

- ↑ [4]Nathan, David L., "A “New” Proto-Cuneiform Tablet", Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin 4, 2003

- ↑ Wagensonner, Klaus, "Early Lexical Lists and Their Impact on Economic Records: An Attempt of Correlation Between Two Seemingly Different Kinds of Data-Sets", Organization, Representation, and Symbols of Power in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 54th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Würzburg 20–25 Jul, edited by Gernot Wilhelm, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 805-818, 2022

- ↑ Bartash, Vitali, "Children in Institutional Households of Late Uruk Period Mesopotamia", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 105, no. 2, pp. 131-138, 2015

- ↑ Civil, Miguel, "Remarks on AD-GI₄ (a.k.a. "Archaic Word List C" or "Tribute")", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 65, pp. 13-67, 2013

- ↑ Krispijn, Theo J.H., "The Early Mesopotamian Lexical Lists and the Dawn of Linguistics", Jaarbericht Ex Oriente Lux 32, pp. 12-22, 1992

- ↑ Englund, Robert K., "Texts from the Late Uruk period", In Pascal Attinger and Markus Wäfler, eds. Mesopotamien. Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. Annäherungen 1. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/1, Pp. 15-233. Fribourg: Universitätsverlag, 1998

- ↑ Veldhuis, Niek C., "How did they Learn Cuneiform? 'Tribute/Word List C' as an Elementary Exercise", in Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis, eds. Approaches to Sumerian Literature. Studies in Homour of Stip (H.L.J. Vanstiphout). Cuneiform Monographs 35. Pp. 181-200. Leiden: Brill/STYX, 2006

- ↑ Ross, Jennifer C., "Lost: The Missing Lexical Lists of the Archaic Period", Strings and Threads: A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, edited by Wolfgang Heimpel and Gabriella Szabo, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 231-242, 2022

Further reading

- [7]Born, Logan, and Kathryn Kelley. "A Quantitative Analysis of Proto-Cuneiform Sign Use in Archaic Tribute." Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin, 2021

- Charvát, Petr, "On People, Signs and States – Spotlights on Sumerian Society, c. 3500–2500 B.C.", Prague: The Oriental Institute, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 1998

- Charvát, Petr. "Cherchez la femme: The SAL Sign in Proto-Cuneiform Writing". La famille dans le Proche-Orient ancien: réalités, symbolismes et images: Proceedings of the 55e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Paris, edited by Lionel Marti, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 169-182, 2021

- Diaco, Maddalena. "The Signs For Buildings in the Proto-Cuneiform." Rivista di Preistoria e Protostoria delle Civiltà Antiche Review of prehistory and protohistory of ancient civilizations 43, pp. 35-52, 2020

- [8]Englund, Robert K. "Proto-cuneiform account-books and journals." Creating Economic Order: Recordkeeping, Standardization and the Development of Accounting in the Ancient Near East , Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch [eds.], Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, pp. 23-46, 2004

- [9]Englund, Robert K. "Late Uruk period cattle and dairy products: Evidence from proto-cuneiform sources." Bulletin of Sumerian Agriculture 8.2, pp. 33-48, 1995

- [10]Englund, Robert K., "The Smell of the Cage", in Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2009:4, 2009

- Englund, Robert K, "Late Uruk Pigs and Other Herded Animals", in: U. Finkbeiner, R. Dittmann and H. Hauptmann, eds., Festschrift Boehmer Mainz pp. 121-133, 1995

- Friberg, J, "Numbers and Measures in the Earliest Written Records", Scientific American, vol. 250, no. 2, pp. 110–118, 1984

- Glassner, J-J. "Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Diverse Collections." The Journal of the American Oriental Society 119.3, pp. 547-547, 1999

- Green, M. W., "Animal Husbandry at Uruk in the Archaic Period", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–35, 1980

- Kelley, Kathryn. Gender, age, and labour organization in the earliest texts from Mesopotamia and Iran (c. 3300-2900 BC). Diss. University of Oxford, 2018

- Klein, Jacob, "Six New Archaic Tablets From Uruk", vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 161-174, 2004

- Langdon, Stephen Herbert, "Pictographic Inscriptions from Jemdet Nasr excavated by the Oxford and Field Museum Expedition", Oxford editions of cuneiform texts 7, Oxford University Press, 1928

- [11]Nissen, Hans-Jörg. "Uruk: Early Administration Practices and the Development of Proto-Cuneiform Writing." Archéo-Nil 26.1, pp. 33-48, 2016

- Nissen, HansJörg; Damerow, Peter; Englund, Robert K., "Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East.", Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993

- Szarzyñska, Krystyna, "Records of Garments and Cloths in Archaic Uruk/Warka", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 15, no. 1-2, pp. 220-230, 1988

- Wagensonner, Klaus. "Early Lexical Lists and Their Impact on Economic Records: An Attempt of Correlation Between Two Seemingly Different Kinds of Data-Sets". Organization, Representation, and Symbols of Power in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 54th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Würzburg 20–25 Jul, edited by Gernot Wilhelm, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 805-818, 2022

External links

- Full list of Proto-Cuneiform Signs from CDLI

- Proto-Cuneiform article at CDLI

- Tablet from the Erlenmeyer Collection purchased by the British Museum

- DIscussion of Proto-Cuneiform Lexical Lists at UPenn Museum

- Uruk IV tablet - photos and transliterations - CDLI

- Uruk III tablets - pictures and transliterations - CDLI