Social:Puluwat language

| Puluwatese | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Federated States of Micronesia |

| Region | Poluwat |

Native speakers | (1,400 cited 1989 census)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | puw |

| Glottolog | pulu1242[2] |

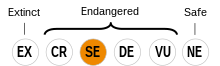

Puluwat is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

Puluwatese is a Micronesian language of the Federated States of Micronesia. It is spoken on Poluwat.

Classification

Puluwatese has two dialects, Pulapese and Pulusukese, both of which have low intelligibility with Satawalese (64%), Woleaian (40%), and Ulithian (21%).[3] Puluwatese does however have slightly higher lexical similarity with Satawalese and Carolinian (88%), Mortlockese (83%), Woleaian (82%), Chuukese (81%), and Ulithian (72%).[3]

Orthography

Vowels

- a - [æ]

- á - [a]

- e - [ɛ]

- é - [e]

- i - [i]

- o - [o]

- ó - [ɔ]

- u - [u]

- ú - [ɨ]

Consonants

- c - [t͡ʃ]

- f - [f]

- h - [h]

- k - [k]

- l - [l]

- m - [m]

- mw - [mʷˠ]

- n - [n]

- ng - [ŋ]

- p - [pʷˠ]

- r - [r]

- ŕ - [ɹ]

- s - [s]

- t - [t]

- w - [w]

- y - [j]

Long vowels and consonants are indicated by doubling their letters.[4]

Phonology

Syllable structure

The syllables in Puluwatese begin with either consonants or geminate consonants followed by a vowel or geminate vowel and can be ended with either a consonant or a vowel.[5] The various syllable structure types are as follows:[6]

- CV: hi 'we'

- CVV: rúú 'bone'

- CVC: mwoŕ 'blow'

- CVVC: niiy 'kill-him'

- CVVCC: wiill 'wheel'

- CVCC: wutt 'boathouse'

- CCV: ppi 'sand'

- CCVV: kkúú 'fingernails'

- CCVC: llón 'in'

- CCVVC: mmwiik 'pepper'

- CCVCC: ppóhh 'steady'

Note that <mw> here stands for a single consonant phoneme /mʷ/ and not a sequence of two separate consonants.

Consonants

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | ||||||

| Stop | p | pʷ | t | tʃ | k | ||

| Fricative | f | s | h | ||||

| Nasal | m | mʷ | n | ŋ | |||

| Rhotic | tap | (ɾ) | |||||

| trill | r | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ||||||

| Approximant | w | ɻ | j | ||||

/tʃ, ɻ/ may also be heard as [ts, ɾ] in free variation among speakers.

In the voicing of consonants, nasals, liquids, and glides are always voiced. Voiceless consonants consist of stops and fricatives and usually follow a pattern of being voiceless initially, weakly voiced medially, and voiceless at the end.[7]

Puluwatese consists of long consonants ccòwo (heavy) and short consonants ppel (light). Long consonants are considered more forceful and are often used to display an emotion such as fear. Such an example is the word for hide-and seek/ tow-the-ghost: likohhomà. In this case, the "hh" long consonant creates a heavy sound that is used to frighten children.[8]

An interesting pattern in consonant replacement occurs where /w-/ and /y-/ glides replace /k-/ in some words. Some of the most commonly heard forms are as follows:[9]

- kapong, yapong-i-y to greet

- kereker, yereker rat

- wo, ko you (polite)

- woow, koow coconut fiber

- yáát, káát boy

- ya-mwar, ka-mwar to hold

- yéé, kéé fishhook

Other consonant interchange patterns involve /c/ and /r/ which can be traced back to Chuukese influence. Oftentimes, the Chuukese consonant /c/ and the Puluwat /r/ correspond such as in the words:[10]

- caw, raw slow

- céccén, réccén wet

- ceec, reec to tremble

/k/ and /kk/ may also be used interchangeably as follows:[10]

- kltekit[clarification needed] small, yátakkit small

- rak only, mákk write

While consonant clusters do not occur in Puluwatese, there are several instances of consonant combinations occurring. These consonant combinations are often interrupted by a vowel referred to as an Excrescent. Sometimes, the intersyllabic vowel is lost and a consonant cluster can occur. The historically noted consonant combinations are as follows:[11]

- kf: yekiyekféngann to think together

- np: tayikonepék fish species

- nf: pwonféngann to promise together

- nm: yinekinmann serious

- nl: fanefanló patient

- nw: yóónwuur canoe part

- ngf: llónghamwol termite

- wp: liyawpenik cormorant

- wh: yiwowhungetá to raise

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | ɨ | u |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Low | æ | a | ɔ |

After sounds /pʷ, mʷ/, /a/ may be raised and fronted as [æ], and back vowels may be slightly centered as [ü, ö, ɔ̈].

/i/ can be heard as [ɪ] when in closed syllables.[12]

Vowel distribution is limited and occur finally[clarification needed]. Vowels may present themselves as short or long and can change to a lower pitch when lengthened.[13] While all syllables are stressed fairly evenly, stressed syllables are often denoted as capitals. The following are two rules that determine stressed syllables:[14]

- Final vowels in CVCV words are stressed such as in hanA hibiscus, klyÒ outrigger boom, ylfA? where?, and ylwE then

- Syllables that follow the letter h are normally stressed: yapawahAalò to dry out, pahAlò to drift away, yekúhÚ rak just a little

Unstressed syllables often occur as excrescent vowels except for when they follow h- and are denoted by breves. Unstressed vowels occur in the following instances:[15]

- Vowels in between reduplicated words are often unstressed:

- ngeŕ- ĕ -ngeŕ to sew

- ngeŕ- ĭ -ngeŕ to gnaw

- pwul- ă -pwul red

- yale- ĕ yái young man

- yál- ĭ -yel retreat

- Vowels between bases and suffixes (directional and first person plural exclusive pronoun suffix):

- fanúw- ĕ -mám our

- mópw- ŭ -ló to drown

- nlike- ĕ -mem- ĕ -ló attack us all

- yállew- ŭ -ló worse

- Vowels following -n, the construct form suffix and the initial consonant:

- n + p: lúkúnĭ paliyewowuh beyond the outer side

- n + k: máánĭ kiiiiló hunger death

- n + m: roonĭ maan floating ripe coconuts

- n + y: wòònĭ Yáley on Yáley

- Vowels in loan words that often contain consonant clusters:

- s+t: Sĭtien Steven

- m+ s: Samĭson Samson

- f+k: Maŕĕkús Markus

- In words that follow the shape of C1V1C2V2C3V3 the V1 and V3 vowels are normally stressed while the V2 has a week stress:

- TilĭmE male name

- yeŕŏmA a tree

Pronouns

Independent pronouns, subject pronouns, and polite vocatives are the three types of pronouns that occur in differing distributions.[16] Independent pronouns occur alone and in equational sentences, they precede noun or noun phrases, as well as subject pronouns, or the prepositions me, and, and with.[16] Subject pronouns never occur as objects and always precede verbs, normally with intervening particles.[16] The use of polite vocatives are rare in daily life and even rarer in texts.[17] However, the known polite vocatives are included in the table below.[18]

| Before proper names, 'person' | Clause - final | |

|---|---|---|

| To a male or males | ko, ŕewe | wo, ko keen ŕewe |

| To a female or females | ne | ne |

| To males or females | keen | kææmi |

The polite vocatives that occur before a proper name may most closely be translated to Mr, Miss, or Mrs, but there are no accurate translations for the clause-final polite vocatives.[18]

Independent and subject pronouns occur in seven propositions: first person singular (1s, 2s, 3s), first person plural inclusive (1p inc), first person plural exclusive (1p exc, 2p, 3p), and is illustrated in the table below.[5]

| Independent Pronoun | Subject Pronoun | |

|---|---|---|

| 1s | ngaang, nga | yiy, wu |

| 2s | yeen | wo |

| 3s | yiiy | ye, ya |

| 1p inc | kiir | hi, hay |

| 1p exc | yææmen | yæy |

| 2p | yææmi | yaw, yɔw |

| 3p | yiiŕ | ŕe, ŕa |

Word order

For transitive sentences, Puluwatese follows a SVO word order but an SV or VS structure for intransitive sentences.[12]

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Counting system

Numbers in Puluwatese are confusing because there is such an intricate system of suffixes for counting different objects. In general, the base of the number stays the same and suffixes for different objects are added onto each base of the number. Suffixes that are added onto the base numbers can significantly alter the meaning of the word such as in the example ye-ray woong (a small turtle) and yee-w woong (a large turtle).[5] For counted objects, suffixes can greatly change their meaning such as in ye-fay teŕeec (a spool of thread) and ye-met teŕeec (a piece of thread).[5] The most common counting suffixes are outlined in the following table.[5]

| Sequential | General -oow |

Animate -ray -man |

Long Objects -fór |

Round Objects -fay |

Flat Objects -réé |

Hundreds -pwúkúw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. yé-ét | yee-w | ye-ray | -ye | -ye | -yé | -ye |

| 2. rúúw | ŕuw-oow | ŕuw-oow | ŕuwe-ray | ŕuwe | ŕuwa | ŕuwa |

| 3. yéél | yeluu-w | yelú-ray | -yelú | -yelú | -yelú | -yelú |

| 4. fáán | f-oow | fa-ray | fó-ór

-fé |

-faa | -faa | -fa |

| 5. liim | lim-oow | lim-man | -lif | -lime

-lif |

-limaa | -lima |

| 6. woon | won-oow | wono-man | -wono | -wono | -wonaa | -wona |

| 7. fúús | féh-úúw | fúú-man | -fúú | -fúú | -fúú | -fúú |

| 8. wall | wal-uuw | walú-man | -wale | -walu | walú | -walu |

| 9. ttiw | ttiw-oow | ttiwa-man | -ttiwa | -ttiwa | -ttiwaa | -ttiwa |

| how many? | fit-oow | fite-ray | -fite | -fite | -fitaa | -fitaa |

Sequential counting is used for rapid counting and can be combined in order to count two or three numbers without intervention. For example, "one, two" can be counted as yét-é-ŕúúw and "three, four" as yei-u-fáán.[5] This sequential counting can be used as a system for rapid pair counting of objects such as coconuts and breadfruit.[19]

The general suffixes are used for objects that do not have a specified suffix. Suffixes for objects are either drawn upon from the general set or any of the other sets.[5]

The animate suffixes are applied to humans, animals, weapons, tools, musical instruments, and other miscellaneous artifacts. The animate suffixes are the only ones to have two different classifiers: -ray and -man with -man being the Chuukese cognate for -mén.[5]

Long object suffixes are used for objects that are long and slender such as rope (yámeey), vehicles (citosa), and cigarettes (suupwa).[5]

Round objects suffixes are used for round objects such as stones (fawú), breadfruit (mááy), eggs (hakúll).[5]

Flat object suffixes are applied to objects such as leaves (éé), clothes (Mégaak: cloth), and mat (hááki).[5]

Ordinals follow the pattern of sequential counting with the prefixes /ya-/, /yó-/, or /yé-/, followed by the base number, and the suffix /an-/ as seen in the following table.[5]

| 1st | ya-ye-w-an |

| 2nd | yó-ŕuw-ow-an |

| 3rd | yé-yelú-w-an |

| 4th | yó-f-ow-an |

| 5th | Yá-lim-ow-an |

| 6th | yó-won-ow-an |

| 7th | ya-féh-úw-an |

| 8th | ya-wal-uw-an |

| 9th | ya-ttiw-ow-an |

| 10th | ya-hee-yik-an |

The names of the days of the week for Tuesday through Saturday are the ordinals from 2nd through 6th without the suffix /an-/. Monday is sometimes referred to as ya-ye-w (1st) and Sunday ya-féh-úw (7th), but more commonly known as, hárin fáál (ending sacredness) and ránini pin (sacred day).[20] However, Chuukese words for the names of the week are more often heard but with a Puluwat accent.[20]

| Monday | seŕin fáán |

| Tuesday | yóŕuuw |

| Wednesday | yewúnúngat |

| Thursday | yeŕuuwanú |

| Friday | yelimu |

| Saturday | yommol |

References

- ↑ Puluwatese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Puluwatese". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/pulu1242.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Puluwatese". Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/18/language/puw/.

- ↑ Puluwatese language on Omniglot

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 Elbert (1974).

- ↑ Elbert (1974), pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 2.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Elbert (1974), p. 5.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 10.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lynch, Ross & Crowley (2002).

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 11.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 13.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), pp. 13–14.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Elbert (1974), p. 20.

- ↑ Elbert (1974), p. 25.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Elbert (1974), p. 24.

- ↑ Bender & Beller (2006).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Elbert (1974), p. 114.

- Elbert, Samuel H. (1971). Three Legends of Puluwat and a Bit of Talk. Pacific Linguistics Series D. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi:10.15144/pl-d7. ISBN 978-0-85883-078-3. http://sealang.net/archives/pl/pdf/PL-D7.pdf.

- Elbert, Samuel H. (1972). Puluwat Dictionary. Pacific Linguistics Series C. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi:10.15144/pl-c24. ISBN 978-0-85883-082-0. https://archive.org/details/puluwatdictionar0000elbe.

- Elbert, Samuel H. (1974). Puluwat Grammar. Pacific Linguistics Series B. Canberra: Linguistic Circle of Canberra, Australian National University. pp. 1–56. doi:10.15144/PL-B29. ISBN 0-85883-103-1. https://archive.org/details/puluwatgrammar0029elbe/page/1.

- Lynch, John; Ross, Malcolm; Crowley, Terry (2002). The Oceanic Languages. Richmond [England]: Curzon. ISBN 0700711287. OCLC 48929366.

- Bender, Andrea; Beller, Sieghard (2006). "Numeral Classifiers and Counting Systems in Polynesian and Micronesian Languages: Common Roots and Cultural Adaptations". Oceanic Linguistics (University of Hawai'i Press) 45 (2): 380–403. doi:10.1353/ol.2007.0000.

External links

- Puluwatese lexical database with English glosses archived with Kaipuleohone

Template:Languages of the Federated States of Micronesia Template:Micronesian languages

|