Social:Tail suspension test

The tail suspension test (TST) is an experimental method used in scientific research to measure stress in rodents. It is based on the observation that if a mouse is subjected to short term inescapable stress then the mouse will become immobile. It is used to measure the effectiveness of antidepressant-like agents but there is significant controversy over its interpretation and usefulness.

History

The TST was introduced in 1985 due to the popularity of a similar test called the forced swim test (FST). However this test only recently became popular in the 2000s where data has shown that animals do show a change in behavior when injected with antidepressants. TST is more reliable when done in conjunction with other depression models such as FST, learned helplessness, anhedonia models and olfactory bulbectomy.[1]

Modeling depression

Depression is a complex multi-faceted disorder with symptoms that can have multiple causes such as psychological, behavioral, and genetics. Since there are so many variables it is hard to model in a lab setting. Patients with depression do not always show the same set of symptoms and often present with co-occurring psychiatric conditions.

A major difficulty in modeling depression is that psychiatrists who clinically diagnose depression follow the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM IV) of the American Psychiatric Association, which involves self-reporting from patients on how they feel. Since animals cannot explain to us how they feel, animals cannot be diagnosed as clinically depressed.[2] While there are theories that animals can experience a condition similar to depression, it is important to keep in mind that depression is, by definition, a human disease. Human and animal brains are considerably different, and care must be taken when interpreting animal behavior and assigning emotional states to various behaviors.

However, there are discrete elements of depression that can be modeled in a lab setting.[3][4] Stress induced immobilization is a behavior that can be useful in modelling aspects of depression. If a rodent is subjected to the short term inescapable stress of being suspended in the air it will develop an immobile posture. Immobility in the TST can be interpreted as the animal ceasing to put in the effort to try to escape. This is often interpreted as behavioral despair, and could be considered a model of the hopelessness and despair experienced by those with depression.[1]

The main strength of the tail suspension test is its predictive validity– performance on the test can be altered by drugs that improve depressive symptoms in people. Specifically, if antidepressant agents are administered before the test, the animal will struggle for a longer period of time than if not and exhibit more escape behaviors.[1] Thus, it is widely used for assessing the antidepressant effects of new pharmacological compounds.

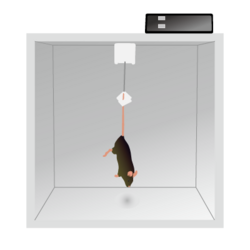

Procedure

The animal is hung from a tube by its tail for five minutes approximately 10 cm away from the ground. During this time the animal will try to escape and reach for the ground. The time it takes until it remains immobile is measured. Each animal is tested only once and out of view from the other animals. Within the study there should be two sets of rats, one group which is the control which has been injected with saline and the group being tested which has been injected with the antidepressant-like agents.[5]

Controversy

There are mixed opinions about the TST. A common criticism is that it can be weeks before a noticeable effect is observed in patients who take antidepressants regularly, however the TST only measures one acute antidepressant dose for 5–6 minutes.[citation needed]

The TST has predictive reliability for known antidepressant agents. However, when testing drugs of unknown mechanisms, the prediction rate is unclear. While the TST detects NK1 receptor antagonists, which have known antidepressant action, it doesn't detect CRF1 receptor antagonists which also have antidepressant functions.

Some consider the TST to be a test of antidepressant function, rather than a model of depression itself.[6] This is largely because the test measures behavioral response to a short-term stressor, whereas human depression is a long-term condition.[6]

Difference from the forced swim test

TST is more sensitive to antidepressant agents than the FST because the animal will remain immobile longer in the TST than the FST.[1] The FST is not as reliable as the TST because the immobility in the animal could be due to the shock of being dropped in water. This also risks hypothermia.[7] While the mechanisms through which the TST and FST produce stress are unknown it is clear that while overlapping the tests produce immobility through stress differently.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Cryan, John F.; Mombereau, Cedric; Vassout, Annick (2005). "The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: Review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 29 (4–5): 571–625. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. PMID 15890404.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (fifth ed.). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

- ↑ Koob, George; Zimmer, Andreas (2012). "Animal models of psychiatric disorders". Neurobiology of Psychiatric Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 106. pp. 136–166. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52002-9.00009-7. ISBN 9780444520029.

- ↑ Cryan, J F; Mombereau, C (13 January 2004). "In search of a depressed mouse: utility of models for studying depression-related behavior in genetically modified mice". Molecular Psychiatry 9 (4): 326–357. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001457. PMID 14743184.

- ↑ "Tail Suspension Test". http://www.research.psu.edu/arp/experimental-guidelines/rodent-behavioral-tests-1/rodent-behavioral-tests.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hoffman, Kurt Leroy (2016). Modeling Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Laboratory Animals, 2 - What can animal models tell us about depressive disorders?. Woodhead Publishing. pp. 35–36. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100099-1.00002-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100099-1.00002-9. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ↑ Liu, X; Peprah, D; Gershenfield, H.K (2003). "Tail-suspension induced hyperthermia: a new measure of stress reactivity.". J Psychiatr Res 37 (3): 249–259. doi:10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00004-9. PMID 12650744.

|