Social:Wildfire emergency management

Wildfires are outdoor fires that occur in the wilderness or other vast spaces.[1] Other common names associated with wildfires are brushfire and forest fire. Since wildfires can occur anywhere on the planet, except for Antarctica, they pose a threat to civilizations and wildlife alike.[2] In terms of emergency management, wildfires can be particularly devastating. Given their ability to destroy large areas of entire ecosystems, there must be a contingency plan in effect to be as prepared as possible in case of a wildfire and to be adequately prepared to handle the aftermath of one as well.[3]

Emergency management has four distinct phases that create the management process. These phases are mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery.[4] While each phase has a distinct role in the emergency management process, there are aspects of each that interconnect with others. A management process without any one of the four phases could be deemed incomplete and inadequate.[5] Mitigation is easily defined as prevention. Preparedness is the act of changing behaviors or processes to reduce the impact a disaster may have on a population or group.[6] Response is assembling teams or units of emergency service to the area of disaster. Finally, recovery aims to restore the area affected by the disaster to its condition prior to the disaster.[7]

Introduction

In order to exercise efficient emergency management, states susceptible to wildfires have collaborated to develop the Firewise Communities USA Recognition Program. The Firewise Communities Program focuses on reducing the loss of life and property, in terms of wildfires, by providing resources to allow communities to build responsibly in natural surroundings and assist one another in preparing for as well as recovering from wildfire. Communities enrolled in the Firewise Communities Program are bound to mitigation guidelines, which require firewise communities to develop and implement action plans to make properties safer from wildfire.[8] Firewise communities organize community members in scheduled meetings to connect citizens to fire fighters, wildfire researchers, and state forestry personnel to educate citizens in terms of wildfire risks. Thereby, informing citizens of risk factors for the development of wildfires and how to prevent as well as prepare for a wildfire. In terms of recovery, firewise communities receive preferential treatment and tend to acquire additional resources and emergency assistance after a wildfire.[9] To be eligible for a membership in the FireWise Communities Program, a community must verify susceptibility to wildfire by acquiring a wildfire risk assessment from the local fire department or forest service. Then, the community must form a firewise committee and action plan as well as contribute two dollars per capita toward firewise activities. Finally, the community submits a membership application to a firewise associate to be considered for recognition as a firewise community.[10] There are currently 40 states with communities recognized as members of the Firewise Communities Program, including Arizona, California , Colorado, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas , and North Carolina.[11]

Causes and effects of wildfires

Wildfires are different from other fires in their size, speed, and unpredictability. Wildfires can occur due to natural or man-made elements. The four most common natural elements that can cause a wildfire are lightning, an eruption from a volcano, sparks from a rockfall, and spontaneous combustion.[12][13] The most common man-made causes for wildfires include debris burning or other carelessness and arson. While not as common as arson or intentionally starting a fire, the improper disposal of a cigarette can cause a fire that could become uncontrollable.[14] The most dominant cause of wildfires differs around the globe. Within the United States, the most common natural cause for wildfires has been found to be lightning strikes. Across the world, however, intentional ignition can be identified as the most common man-made cause for uncontrollable fires.[15]

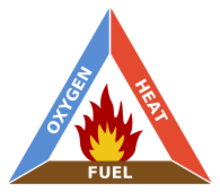

According to the North Carolina Forest Service (NCFS), during 2010 there were 4,053 separate wildfires in North Carolina, which burnt a total of 14,095 acres. They report the cause of the largest number of wildfires for 2010 was the intentional burning of debris, which resulted in 1,617 wildfires. Incendiary substances, (such as gasoline or propane) were involved in another 805, and the use of machinery a further 435. NCFS also indicate 162 of the wildfires in 2010 were caused by smoking, 69 were caused by lightning, and 34 were the result of poorly managed campfires or other camping-related activities.[16] Determining the causes of wildfires is integral to understanding how wildfires develop, which allows for the development of preventative measures to reduce wildfire vulnerability and minimize harmful effects.[17] In terms of wildfires, there is often a vast amount of combustible materials to sustain a burn for en extended amount of time. Areas that are higher in moisture, such as dense forests, are less susceptible to burn as they have a natural provision of shade and humidity, which both can delay ignition.[18] Wildfires have what are known as fronts which is the portion of the fire that meets new, unburned material, providing additional fuel for the oncoming fire.[19] Wildfires can also move at an incredible pace; in forests and densely wooded areas, wildfires can burn at a rate of almost 7 miles per hour.[20] Another threat of wildfires is their ability to jump. Embers and other ignited material such as leaves and other debris can be carried by the wind to an area that has not had any contact with the fire thus far. This could possibly ignite fire in a separate area, making the wildfire much more dangerous and more difficult to contain.[21]

Whether a wildfire can be contained depends on the intensity at which the fire burns. In the United States, wildfire intensity is measured by the rate at which the fire spreads and the degree of combusted heat produced by the flames. There are two types of fire intensity: reaction intensity, which is determined by the amount of heat released by the fire per unit of area burned and fire line intensity, which is determined by the length of the flames at the edge of the fire and height of scorch marks on affected trees. Higher scorch marks result from highly intense fires and typically cause trees to deteriorate significantly to the point of needing to be removed from the burned area. In addition to consuming trees, more intense wildfires tend to produce substantial amounts of smoke by consuming flammable material located on the ground. Flammable ground litter, also referred to as duff, that has less moisture contributes to the complete destruction of groundcover, which directly contributes to soil burning and erosion.[22] The types and amount of ground litter directly influence the intensity of a wildfire. For instance, a wildfire requires 12 tons of pine litter to burn at high intensity whereas a high intensity wildfire would only require 7 tons of hardwood litter. However, wildfires require 60 tons of heavily chopped debris to burn at high intensity, but only require 40 tons of medium chopped debris for high intensity fuel.[23] As explained further in the recovery section of this article, the burning intensity of a wildfire determines the extent of the damage caused by the fire and influences the recovery strategies utilized by emergency management personnel.

Mitigation

Mitigation efforts are taken to prevent events from becoming disasters and from preventing disasters from occurring completely. Mitigation is the efforts that are taken to ensure that the loss of life and property is limited in the event of a disaster.[5] The North Carolina Forest Service (NCFS) emphasizes measures North Carolina residents and visitors can take in order to effectively prevent the development of man-made wildfires. NCFS personnel suggest not setting fires on dry, windy days because dry debris can ignite easily and lighter debris, such as grass and leaves, can be easily transported via the wind. Therefore, individuals are encouraged to avoid burning lighter debris, which could be better utilized as compost. Individuals are also encouraged to grind out cigarettes in dirt as opposed to on tree stumps or other debris and to dispose of cigarettes in vehicle ash trays. In addition to limited burning and disposal of burnt matter, NCFS suggest individuals monitor the intentional burning of acres and keep materials handy for eliminating the fire, such as water and shoveled dirt. Meanwhile, NCFS campfire guidelines indicate campers should construct small campfires with small amounts of debris and only add additional, larger debris as the fire grows. Campers are also instructed to maintain a 10-foot diameter clearing around the campfire to prevent the fire from spreading to surrounding debris and to never leave a campfire unattended. The campfire should be continually monitored with water and shoveled dirt handy in the event the fire becomes uncontrollable.[24] Thereby, preventing minimal or contained fires from developing into devastating wildfires.

The NCFS uses a database referred to as "signal 14" to monitor the daily fire activity in the state of North Carolina. The data contained within the signal 14 database is an estimation of the occurrence of wildfires throughout the state, with the exception of wildfires located on federal property. For instance, signal 14 statistics indicate approximately 1,252 wildfires occurred between January and April 2012, of which 45 occurred in April. The NCFS tracks wildfires in order to map out areas where wildfires occur and assess which areas are more prone to the development of wildfires. In terms of mapping wildfires, North Carolina is divided into twelve districts and each one contributes daily counts of any wildfires to the signal 14 database. Thereby, assisting the NCFS in determining the vulnerability, of each district, to wildfires.[25]

Preparation

Like with most natural disasters and emergency situations, being prepared is crucial to saving life and property. Wildfires are a natural process of the forest and are ecological beneficial to forests and wildland areas.[26] However, wildfires become a problem when they begin to move to areas that are populated with people. This generally happens in areas that have settlements and other built environments interacting with natural woodland areas or areas that have potential fuel for wildfires and these areas are called the wildland-urban interface (WUI).[27] With this increase of people and property vulnerable to wildfires, policies and programs were developed to better prepare for wildfires.

Most of the United States ' policies for wildfires usually favored suppression of the fire over prevention with the U.S. Forest Service taking the lead role.[28] However, over time, the states began to take a more active role in wildfire prevention. This switch from suppression to prevention and the increasing role of states in wildfire prevention was the product of increasing knowledge of wildfires and several Congressional acts, like the Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act (CFAA) of 1978, which provides matching grant money for rural fire departments for equipment and training.[29] This increased role of state agencies in wildfire prevention would require an intergovernmental coordination to better deal with preparing and preventing wildfires. This intergovernmental coordination was the product of congressional legislation for equipment, training, and money for state and local fire crews and new federal environmental laws that require public comment and participation which leads to more state participation in the development, and implementation of wildfire management plans but federal agencies have a senior partner role in this relationship due to their experiences with wildfire suppression and the resources that they have available.[30] The states role in this coordination soon changed because of the challenges that faces wildfire management in the wildland-urban Interface and the changes in land use policies that are better handled by organizations that focus on prevention style policies.[31] This new intergovernmental coordination for wildfires now allows for local and state organizations with help develop policies for preparing and preventing wildfires.

While living in the wildland-urban interface, homeowners must be prepared for wildfires that threaten their homes. People move to the wildland areas for many reasons. These reasons include the naturalness of the area, the aesthetics of the landscape, the wildlife, recreation, and for privacy.[32] With people moving to these areas, there are some procedures and strategies that can be implemented to prepare for wildfires. These strategies include defensible space, planting of fire resistant vegetation, fire-retardant building materials, and sprinklers to slow the progression of the fire.[33] While these measures will help the homeowners to prepare for wildfires, not all homeowners in the U.S. use all of these methods for the properties. Since the U.S. has a wide variety of ecosystems and unique people that live in different places, different parts of the county adopt different preparedness methods based on multiple factors of which includes the value of the forested landscape.[34] An example of the different perceived effectiveness of these measures is that homeowners in Minnesota are more inclined to use water-based technology, While Florida homeowners have higher opinion on the efficacy of fire-retardant building materials.[35] While these differences in perceived effectiveness of preparedness measures vary greatly, many homeowners regard vegetative fuel reduction as the most effective method for preparing for wildfires.[36]

To help homeowners prepare for wildfires, community support and organizations can help provide information, support, and training to help prepare for a wildfire event. For a community to create a preparedness strategy that will work efficiently against wildfires, four elements must be included in the foundation; these are landscape, government, citizens, and community.[37] Landscape is a key element because it describes the local vegetative conditions that can fuel the wildfire, the location of the community which can motivate people to take responsibility for community wildfire preparedness, and the landscape promotes attachment to place which can promote a positive bond between the people and the land.[37] The government is a key element because governmental representatives can collaborate with local officials for community preparedness and thereby opening the communities up to accessing funds, equipment, and training that would otherwise would not be available.[37] Citizens are a key element in community preparedness because citizens apply their knowledge and skills to help the community and thereby empower their neighbors to help out in the preparedness process.[38] The community is the final key element for community preparedness because it takes multiple people and collaborative groups to create to framework for community preparedness.[38] By using these key elements, community can create a community preparedness program to better prepare themselves when wildfires threaten their community. Some issues that must be overcome for community preparedness are developing educational materials that reflect the intended audience and local community, building connections and networks between landowner and agencies, coordination between the different local, state, and federal agencies, and recognize the importance of individual responsibility for preparing their homes.[39] Examples of community preparedness programs distributed throughout the U.S. includes: the Firefree program in Oregon, the Firesafe councils in California , and the nationwide Firewise Communities/USA.[40] Each of these educational programs provides communities with information about how to prepare for wildfires. The goal of these programs is to create awareness about wildfire risk, knowledge about wildfire safety, and stewardship ethic beyond defensible space around individual homes.[41]

The United States is not only country that has wildfires as a natural disaster. Australia has had it fair share of wildfires that has caused significant effects like loss of life and property damage, an example of which includes the Ash Wednesday wildfire in 1983 which resulted in 47 deaths, and over 2,000 buildings destroyed.[42] Through their experiences, the Australians developed their own approach to wildfire management. Their approach to wildfires is called "Stay and Defend or Leave Early".[43] This approach was the result of investigations into the fatalities of major Australian wildfires. Research as found that most fatalities occur when people try to leave at the last minute and were the result of radiant heat exposure and vehicle accidents.[44] Leaving at the last minute can be fatal because of the nature of wildfires and how they can cut off escape routes during their movement. Another fact found by these investigations is that homes catch fire not through direct contact of the flames but by embers landing inside or on the house.[44] This knowledge of how buildings burn during wildfire events can help property owners to identify potential ignition sources and quickly handle the threat to their property.

Response

Wildfires can cause great widespread devastation in short time spans.[45] According to the United States Fire Administration, wildfires were responsible for an average of 12.0 deaths per million populace in 2008. In North Carolina, the death rate was found to be 14.4 per million populace.[46] However, despite their low responsibility in loss of life, wildfires are responsible for a massive amount of property loss. In 2009, the U.S. Fire Administration reported a loss of almost 6 million acres from a total of 78,792 wildfires.[47] In the event of a wildfire, those who live in close proximity are advised by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to notify emergency services and, if time and safety permits, secure the following protections to their home before evacuating:

- Fill as many containers (pools, hot tubs, garbage cans, etc. with water).

- Place lawn sprinklers on the roof and near any above-ground fuel tanks.

- Wet the roof.

- Place a ladder against the side of the house.

- Turn on as many lights in the house as possible. This increases the houses's visibility through smoke.

- Close windows and doors but leave them unlocked for firefighters' easy access.[48]

Emergency response occurs among professionals as well as affected individuals. The first aspects of recovery include local agencies that are nearest to the disaster: firefighters, Emergency Medical Services, local police. Assessments must be conducted to determine the basic human needs that are present and efforts are taken to ensure these needs are met as quickly as possible. Assignments are delegated depending on the current needs - search and rescue, distribution of resources, immediate temporary relocation for displaced individuals. The Federal Fire Prevention Act enabled a national reporting system for fires around the country. This system is called the National Fire Incident Reporting System or NFIRS. The purpose of this system is to collect demographics, statistics, characteristics, and other pertinent information about fires which is compiled into a database. The goals of NFIRS are to assist state and local governments in developing a concrete method for reporting fires and developing a method of analyzing them. NFIRS was also created to provide national data on fires. By using NFIRS, emergency managers can access data about loss of life and property, as well as causes of the fires that caused such loss. While participation in NFIRS is voluntary, all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia participate.[49]

In the event of a wildfire, floods and landslides can often occur after the burn due to the drastic changes the fire can have caused in the terrain and the condition of the ground. Those who live within the proximity of a wildfire are susceptible to experiencing loss and damage from these events. Floods and landslides can occur long after the fire has ceased its burn; fires leave the ground charred with little to no vegetation, which normally absorbs rainfall. Without the vegetation, the rainwater can cause flash floods for up to five years after a wildfire. Flooding after a wildfire often includes the debris left behind after a fire, which can turn a flood into a mudslide, which can cause significant amounts of damage.[50]

In the summer of 2011, a wildfire burned in Pender County, North Carolina for almost three months before it was 100% contained. Named the "Juniper Road Fire", this wildfire that ravaged Pender County burned over 31,000 acres. Caused by a lightning strike on June 19, 2011, the fire spread quickly and despite having over 200 individuals fighting to contain it, the fire burned for an excess of almost three months.[51] Fire crews, both local and distant, some from as far as Alaska, offered their aid to contain this wildfire. By focusing their attention on hot spots, the crews were able to contain more and more of the fire, though not nearly as quickly as they would have liked. Had the area not received a downpour of rain in early August, the fire may not have been contained when it was. Fire crews reported that the fire could have burned much longer had the rain not come. When crews determined that the fire was 92% contained, it had cost an estimate of $3.5 million to fight.[52]

Recovery

Recovery, in terms of emergency management, refers to providing immediate support to a community affected by a disaster in order to repair the infrastructure and return the community to normal operation status.[53] In terms of wildfires, post disaster recovery efforts following a wildfire begin with assessing fire damage to trees, shrubs, and soil. Wildfire recovery strategies are dependent on the intensity of the fire (scale of low to high), which determines the extent of fire damage and effective forest restoration. Low intensity fires consist of minimal damage to small trees without burning all of the forest and the majority of leaves still remain on the trees. Meanwhile, wildfires burning at moderate intensity result in the majority of the leaves and ground cover being consumed by flames while the largest, most healthy trees remain intact. The most devastating wildfires burn at high intensity and destroy 50 to 100% of the forest, including all the ground cover. Landowners, with woodlands affected by wildfire, are encouraged to map out the area of damaged property to assess the burn intensity and determine methods for restoring the area. Recovering from high intense fires requires additional measures to prevent soil erosion such as spreading slashed limbs and straw over soil to reduce contact with rain water. Landowners should be advised the risk of soil erosion increases when:

- the burn intensity is high

- all the ground cover is consumed

- rain falls rapidly

- the tree canopy is destroyed

- land is located downhill from other burned property

- the slopes are steep

Landowners with these circumstances are advised to spread slashed wood and straw over the burned areas of ground to restrict the impact of rainwater, which allows water to disperse without contributing to erosion. Meanwhile, straw wattles, which are long strands of plastic netting, should be draped over slopes to prevent soil from slipping downhill. In addition to preventing soil slips, landowners are also advised to construct waterbars, which are mounds of rock or logs placed on the slope at a diagonal, to divert water off roads and trails. After soil is stabilized recovery efforts focus on removing heavily damaged debris from affected areas and salvaging less damaged lumber. To determine the extent of tree damage, the landowner needs to examine the bark, buds, and roots of burned trees to assess which trees can be salvaged and which trees need to be replaced. The bark on the tree protects the cambium, which transfers nutrients through the tree and thicker bark prevents high intensity fire from affecting the cambium. Thick, non-scorched bark is a sign of a tree with the possibility of survival. In addition to tree bark, trees with chances for survival have buds firm to the touch with bendable stems. Salvageable trees also have tree roots, which were not scorched because of depth in the ground. Landowners are encouraged to photograph any trees marked for removal as proof of assessed damage because trees lost due to wildfire can be written off on a federal income tax return as a casualty loss. Thereby, allowing landowners to claim up to $10,000 to invest in restoring the landscape. In order to restore areas damaged from wildfire, additional soil is dispersed while trees and shrubs are replanted. Landowners are encouraged to replant trees more resistant to wildfire.[54][55][56]

In addition to assessing damage to landscape, owners of property damaged by wildfire have to assess structural damage as well. Citizens are advised not to return home following a wildfire until fire personnel determine the area is safe. Individuals returning home following a wildfire are instructed to avoid down or exposed power lines and exercise caution when entering burnt areas because hot spots of burning debris may still be present. To minimize risk, owners are advised to spray down debris with water to put out any residual fire and wear closed masks to prevent inhaling dust from debris. Persons participating in removal of debris and clean up are recommended to wear thick soled shoes and leather gloves to protect themselves against exposure to harmful debris.[57] Individuals are also encouraged to inspect their homes for embers that may have been left behind by the wildfire and may still be burning in the attic or other spaces. Homeowners are also advised to check circuit breakers in the event of a power outage following a wildfire because wildfires can cause breakers to short out. To reduce the risk of incendiary fires in the future, individuals are encouraged to inspect any propane or oil tanks that may have been exposed to the wildfire. Homeowners are also advised to test the structural support of the home and remove any trees determined to be unstable, which could easily fall on the home. Meanwhile, homeowners are encouraged to remove debris from the roof, gutters, and air conditioning units to prevent further fire ignitions.[58]

Oakland case study

When a wildfire reaches areas that are populated with people, massive damage can occur. This combination of a wildfire threatening a major urban area was shown with the Oakland Wildfire of 1991. The Oakland Wildfire was started by a fire of suspicious origin on October 19, 1991.[59] The fire became out of control on October 20 after the sparks from smouldering embers were carried by strong local winds. The fire began to grow after the embers landed on nearby vegetation and the wind began to move the flames in several directions at the same time.[60] Soon, many homes in the neighborhoods of Hiller Highlands, Buckingham Place, and many others were threatened by the flames and fire crews began to scramble to put out the flames. The fire raged out of control until around 5 pm, when cooler temperatures and decreasing wind speeds slowed the progression of the fire.[61] During the course of the event, the fire became a firestorm when the heat, gases, and the motion of the fire created its own weather conditions.[62] The fire caused significant damage to Oakland and the surrounding areas. The fire killed 25 people, which included emergency personnel, destroyed 2,449 homes, and caused an estimated $1.5 billion in damage.[63] The response to this fire was swift, however, the fire and winds made it difficult to extinguish.[64] There were also several issues with the response. Communications broke down due to the intensity of the fire, rapid spread of the fire, and the communication systems were jammed due to the volume of telephone and radio traffic [65] The narrow roads of the neighborhoods could not allow both fire crews and civilians to leave or enter the area, which resulted in vehicles being trapped for hours and caused the deaths of eleven victims.[66] Evacuation also caused an issue due to high winds, heavy smoke, and narrow roads, which caused confusion for both fleeing residents and the fire crews. The evacuations were conducted on a one-on-one basis because the Emergency broadcast system was deemed inefficient for the task, this would result in many people being caught off guard by the fire.[67] The combination of the weather factors, intensity of the fire, and the breakdown in communication and evacuation caused the response to the wildfire to be slow and ineffective until the change in weather conditions during the evening. This wildfire event shows the danger of fire in the wildland/urban interface.

See also

- Pyrotron, a device designed to help firefighters better understand how to combat the rapid spread of wildfires

- remote monitoring of wildfires

References

- ↑ Federal Fire and Aviation Operations Action Plan, 4.

- ↑ Stephen J. Pyne. "How Plants Use Fire (And Are Used By It)". NOVA online. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/fire/plants.html.

- ↑ "International Experts Study Ways to Fight Wildfires". Voice of America (VOA) News. 2009-06-24. http://www1.voanews.com/english/news/a-13-2009-06-24-voa7-68788387.html.

- ↑ Richard Sylves (2008). Disaster Policy & Politics: Emergency Management and Homeland Security. University of Delaware: CQ Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-87289-460-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sylves, p. 21.

- ↑ Drabek, Thomas E. (1986). Human System Responses to Disaster. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-387-96323-5.

- ↑ Sylves, p. 24.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association. "Talking to Your Neighbors About Firewise". Firewise Communities/USA Recognition Program. National Fire Protection Association. http://www.firewise.org/Communities/USA-Recognition-Program/Talking-to-your-neighbors-about-Firewise.aspx.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association. "Program Benefits". Firewise Communities/USA Recognition Program. National Fire Protection Association. http://www.firewise.org/Communities/USA-Recognition-Program/Benefits-to-becoming-Firewise.aspx.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association. "Program Criteria". Firewise Communities/USA Recognition Program. National Fire Protection Association. http://www.firewise.org/Communities/USA-Recognition-Program/Program-criteria.aspx.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association. "Firewise Communities/USA Recognized Sites". Firewise Communities/USA Recognition Program. National Fire Protection Association. http://submissions.nfpa.org/firewise/fw_communities_list.php.

- ↑ "Wildfire Prevention Strategies". National Wildfire Coordinating Group. March 1998. p. 17. http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/docs/wfprevnttrat.pdf.

- ↑ Scott, A (2000). "The Pre-Quaternary history of fire". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 164 (1–4): 281. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00192-9. Bibcode: 2000PPP...164..281S.

- ↑ Causes of Wildfires

- ↑ Pyne, Stephen J.; Andrews, Patricia L.; Laven, Richard D. (1996). Introduction to wildland fire (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-471-54913-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=yT6bzpUyFIwC&q=world+start+ignition+wildfire&pg=PA56.

- ↑ North Carolina Forest Service. "Fires by Cause in North Carolina 1970–2018". North Carolina Division of Forest Resources Fire Reporting System. North Carolina Forest Service. https://www.ncforestservice.gov/fire_control/pdf/Firest%20by%20cause%20in%20nc.pdf.

- ↑ The Fire Triangle , Hants Fire brigade

- ↑ Graham, R., McCaffrey, S., Jain, T.B., "Science Basis for Changing Forest Structure to Modify Wildfire Behavior and Severity", General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-120, 2004

- ↑ Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology, 74.

- ↑ Billing, P., "Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment.", Otways Fire No. 22 - 1982/83 Aspects of fire behaviour. Research Report No.20, 1983

- ↑ Shea, N., "Under Fire", National Geographic, 2008

- ↑ Albini, Frank. "Estimating Wildfire Behavior and Effects". Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station General Technical Report. USDA Forest Service. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1143&context=barkbeetles.

- ↑ North Carolina Forest Service. "Smoke Management Guidelines". North Carolina Forest Service. http://ncforestservice.gov/fire_control/fc_smoke_management_guidelines.htm.

- ↑ North Carolina Forest Service. "Fire Safety Outdoors". North Carolina Forest Service. http://ncforestservice.gov/fire_control/fc_firesafetyoutdoors.htm.

- ↑ North Carolina Forest Service. "Wildfire Statistics". Signal 14 Database. North Carolina Forest Service. http://ncforestservice.gov/fire_control/wildfire_statistics.htm.

- ↑ Davis, Charles (2001). "The West in Flames: The Intergovernmental Politics of Wildfire Suppression and Prevention". Publius 31 (3): 97–110. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a004911. http://publius.oxfordjournals.org/content/31/3/97.short.

- ↑ Jakes, Pamela; Kruger Linda; Monroe Martha; Nelson Kristen; Sturevant Victoria (2007). "Improving Wildfire Preparedness:Lessons form Communities across the U.S". Human Ecology Review 14 (2): 188–197.

- ↑ Davis, p.98.

- ↑ Davis, p.102.

- ↑ Davis, p. 109.

- ↑ Davies, p. 109–110.

- ↑ Nelson, Kristen; Monroe, Martha C.; Johnson, Jayne Fingerman (2004). "The Look of the Land: Homeowner Landscape Management and Wildfire Preparedness in Minnesota and Florida". International Journal of Wildland Fire 13 (4): 321–336. doi:10.1080/08941920590915233.

- ↑ Nelson, p. 323.

- ↑ Nelson, p.333.

- ↑ Nelson, Kristen; Monroe, Martha C.; Johnson, Jayne Fingerman; Bowers, Alison (2004). "Living with fire: homeowners assessment of landscape value and defensible space in Minnesota and Florida, USA". International Journal of Wildland Fire 13 (4): 413–425. doi:10.1071/WF03067.

- ↑ Nelson, p. 420.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Jakes, p. 194.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Jakes, p. 195.

- ↑ Kruger, Linda E.; Agrawal, Shruti; Monroe, Martha; Lang, Erika; Nelson, Kristen; Jakes, Pamela; Sturtevant, Victoria; McCaffrey et al. (2002). Key to Community Preparedness For Wildfire. St Paul, Minn.: Proceedings of the Ninth International symposium on society and management; 2002 June 2–5: Bloomington, Indiana General Technical Report NC-231. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station. pp. 10–17.

- ↑ Sturtevent, Victoria; McCaffey Sarah (2006). "Encouraging Wildand Fire Preparedness:Lessons Learned from Three Wildfire Education Programs". The Public and Wildand Fire Management: 125–136.

- ↑ Sturtevant p. 125.

- ↑ McGee, Tara K.; Russell Stefanie (2003). ""It's just a natural way of life ..." an investigation of wildfire preparedness in rural Australia". Environmental Hazards 5 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.hazards.2003.04.001. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s146428670300024x.

- ↑ McCaffrey, Sarah; Rhodes Alan (2009). "Public Response to Wildfires: Is the Australian "Stay and Defend or Leave Early" Approach an Option for Wildfire Management in the United States". Journal of Forestry (107): 9–15. http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/9391.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 McCaffrey, p. 10.

- ↑ "Fire Information - Wildland Fire Statistics". National Interagency Fire Center. http://www.nifc.gov/fire_info/lg_fires.htm.

- ↑ U.S. Fire Administration. "State Fire Death Rates". U.S. Fire Administration/FEMA. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/statistics/estimates/states.shtm.

- ↑ U.S. Fire Administration. "Total Wildland Fires and Acres". U.S. Fire Administration/FEMA. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/statistics/estimates/wildfire.shtm.

- ↑ FEMA. "During a Wildfire". FEMA. http://www.ready.gov/wildfires.

- ↑ U.S. Fire Administration. "About NFIRS". U.S. Fire Administration/FEMA. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/fireservice/nfirs/about.shtm.

- ↑ FEMA. "Hazards After Wildfires: Floods and Landslides". FEMA. http://www.ready.gov/wildfires.

- ↑ InciWeb. "Juniper Road". InciWeb Incident Information System. http://www.inciweb.org/incident/2371/.

- ↑ Herrera, Ramon (1 August 2011). "Rain Helps after Pender Co. Fire Lingers Into Third Month". ABC News. http://www.wwaytv3.com/2011/08/01/rain-helps-pender-co-fire-lingers-into-third-month.

- ↑ Petak, William (January 1985). "Emergency Management: A Challenge For Public Administration". Public Administration Review 45: 3–7. doi:10.2307/3134992.

- ↑ Oklahoma Forestry Services. "Recovering From Wildfire: a Guide for Oklahoma Forest Owners". Oklahoma Forestry Services. http://www.forestry.ok.gov/Websites/forestry/images/Brochure,%20Recovering%20From%20Wildfire%20for%20web.pdf.

- ↑ Deneke. "Recovering From Wildfire: A Guide for Arizona's Forest Owners". The University of Arizona: Cooperative Extension. University of Arizona. http://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/resourcefile/resource/mblock/recoveringfromwildfire.pdf.

- ↑ Harris, Richard (2001). Recovering from Wildfire: a Guide for California's Forest Landowners. Oakland, California: University of California, Berkeley. p. 14. ISBN 9781601073556. https://books.google.com/books?id=TyQziEnkvx0C&q=recovering+from+wildfire&pg=PA1.

- ↑ American Redcross. "Returning Home After a Wildfire". PreparednessFast Facts: Wildfires. American Redcross. http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/menuitem.53fabf6cc033f17a2b1ecfbf43181aa0/?vgnextoid=9ae2779a32ecb110VgnVCM10000089f0870aRCRD&currPage=a76ad7aada352210VgnVCM10000089f0870aRCRD.

- ↑ "Recovery". Preparedness Fast Facts: Wildfires. American Red Cross. http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/menuitem.53fabf6cc033f17a2b1ecfbf43181aa0/?vgnextoid=9ae2779a32ecb110VgnVCM10000089f0870aRCRD&currPage=560fdb40a30e5210VgnVCM10000089f0870aRCRD.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association (1991). The Oakland/Berkeley Hills Fire. National Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Protection Initiative. http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files/MbrSecurePDF/FIoakland.pdf.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 11.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 12.

- ↑ NFPA, pg. 12.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 3.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 13.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 14

- ↑ NFPA, p. 15.

- ↑ NFPA, p. 16.

External links

- NFPA

- Firewise Communities

- Firewise Landscapes

- Wildfire Management: Federal Funding and Related Statistics Congressional Research Service

|