Software:Discworld Noir

| Discworld Noir | |

|---|---|

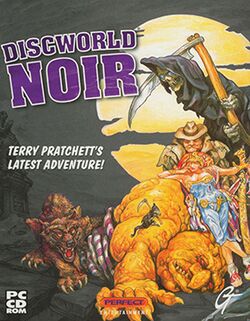

The game's cover features original work by Discworld novel cover artist Josh Kirby. | |

| Developer(s) |

|

| Publisher(s) | GT Interactive |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) | Mark Judge |

| Artist(s) | David Kenyon |

| Writer(s) | Chris Bateman |

| Composer(s) | Paul Weir |

| Series | Discworld |

| Platform(s) | Windows, PlayStation |

| Release | Windows PlayStation

|

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Discworld Noir is a 1999 adventure game developed by Perfect Entertainment and published by GT Interactive. The game is set in Terry Pratchett's satirical Discworld universe, and follows its first and only private investigator as he is given a case leading him into the deadly and occult underbelly of the Discworld's largest city.

The game plays on film noir genre tropes, parodying noir classics such as Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon. Originally released for Microsoft Windows, it was later released for PlayStation by Teeny Weeny Games, the resurrected form of the already insolvent Perfect Entertainment. Pratchett consulted on the story and provided some of the dialogue, being credited for causing "far too much interference."

Gameplay

Discworld Noir is an adventure game, in which players take control of the character of Lewton, visiting various locations in the city of Ankh-Morphok, finding items to help solve puzzles, and conversing with a wide variety of characters. the game's story is divided into a set of acts, in which the player must complete various tasks to advance the story.

Much of the conversations in Discworld Noir focus on a more structured manner than in previous Discworld games. Alongside a greeting function, the player can converse with characters about simple conversation topics, as well as show them items collected during the game, and question them on leads noted down in Lewton's notebook; once a lead is of no further use, its scratched out and unselectable.[1][2]

The game uses a "threaded" structure, in which there are separate "vignettes" that the player may come to at different points. For example, missing a clue early on in the game will cause a character to give it to the player later in the game.[3] In addition to traditional adventure mechanics, the player will later gain the ability for Lewton to transform between a human and a werewolf, allowing them to collect scents to help solve additional puzzles. Like the previous Discworld games, the PlayStation version of the game supports the PlayStation Mouse.[4]

Story

Characters and Setting

Discworld Noir contrasts deeply to the first two games set in the Discworld universe, adopting a more "grittier, darker and more realistic" style in its story,[2] while featuring an original story by Terry Pratchett not derived from any of his novels in the Discworld series.

Like with Pratchett's work, the story parodies a mixture of traditional hardboiled fiction and film noir,[5] as well as a combination of dark fantasy and Lovecraftian horror.[6][7] The film noir elements feature significant references to the 1942 film Casablanca, as well as a heavy use of "discordant" strings and dissonance in its background music,[1] matching to the style of jazz and blues pieces from the early 20th century; multiple references towards the horror elements are made of the works of H. P. Lovecraft.[6]

The game's lead protagonist that players control is Lewton - a former member of the Ankh-Morpork City Watch, who left to become the Discworld's first and only private investigator within the city of Ankh-Morpork. The character is based on the classic private detective figure, with an appearance and jacket reminiscent of noir detectives;[8] PC Zone compared the characters of Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe.[2] Other new characters to the Discworld universe include: Carlotta Von Uberwald - considered a femme fatale figure,[2][9] and one of the primary antagonists; the troll criminal Horst; Ilsa Verbay, a former love interest of Lewton; and Two-Conkers, an Agatean Empire citizen specialized in archeology. The game features some notable characters from the Discworld series, including Commander Vimes, Corporal Nobby and Death.

While the story is an original piece by Pratchett, the writer viewed it like his previous games as in a "parallel Discworld" to that of the novels. Despite this, the game's designer Chris Bateman devised Noir's events to fit in between the stories Feet of Clay and Jingo.[10]

Plot

Lewton, a former member of the Ankh-Morpork City Watch, seeks out work after becoming the Discworld's first (and only) private investigator. He is hired by the mysterious Carlotta Von Uberwald to track down a man named Mundy. The only detail he receives is that Mundy was away in the nation of Tsort, and that he disappeared shortly after he returned to Ankh-Morpork two days ago previously. Accepting the case, Lewton's search leads him to encounter the troll Malachite, who requests his help in tracking down a troll named Therma, and the father of Carlotta's deceased husband, Count Von Uberwald, who hires him to track down his missing dwarven driver, Regin.

While Regin turns up dead in the river Ankh after being murdered while driving fast in the Uberwald's carriage, the other two cases of Lewton's sees him knocked out as he closes in on his objectives: Mundy is murdered after he finds him; while Malachite is murdered when the PI takes him to an arranged meeting with Therma. Lewton's former superior, Commander Vines, strongly suspects him of the murders, but does not agree to his belief they are linked to a spate of recent, ritualistic murders, dubbed the Counterweight Killings, that the Watch are investigating. At the same time, Lewton learns a troll named Horst, an underworld criminal, is after a relic known as the "Golden Sword", which Mundy was supposed to give to him, and which Carlotta is seeking to acquire herself.

Finding Horst believes he has it, and tailed by Horst's associate Al-Khali, a shady dwarf, Lewton finds Mundy hid the relic in a crate that went to the Guild of Archaeologists. Needing help to access it in the Guild's vaults, Lewton turns to help from Ilsa Verbay, a former lover of his who recently returned to Ankh-Morpork with her husband Two-Conkers, an archaeologist from the Agatean Empire. With her help, Lewton recovers the relic, but is hounded by an unknown pursuer when he leaves the Guild. Accidentally dropping the sword in his efforts to escape, Lewton is stabbed in the chest and presumed dead by the Watch. A few days after being buried, Lewton re-emerges alive, but discovers from a talking dog named Gaspode that he has become a werewolf.

Discovering his newfound abilities can be useful, Lewton decides to investigate the Counterweight Killings. His research on the relic leads him to a priest of the goddess Errata, who reveals that the Golden Sword is actually known as the Tsortese Falchion - an ancient blade forged for Errata, which was lost following a major war in Tsort many years ago. Lewton also learns the relic is incomplete - it is missing a jewel that empowers it, and which is believed to be hidden in Ankh-Morpork. Meanwhile, the investigation into the killings reveals they are part of a ritual to summon Nylonathatep, a being from the Dungeon Dimensions. Staking out the site where the final murder in the ritual is to take place, Lewton watches as a werewolf murders Al-Khali, who had been tailing him upon his return from "death".

Before he can pursue the murderer, Carlotta approaches him, revealing she is the head of a guild devoted to Anu-Anu, a forgotten god worshipped by werewolves such as herself. She reveals he was behind the murders when she called on him - though she needed him to kill Mundy, Malachite and Regin because each threatened her and the cult's plans - and that the god was the one who stabbed him; Carlotta revived him as a werewolf, because she believed he could help the cult. Lewton finds himself forced to witness Anu-Anu conduct the ritual to summon Nylonathatep with the Falchion, but the ritual backfires and causes the beast to emerge in Ankh-Morpork, killing Anu's mortal form and several of the cultists.

Lewton discovers a second cult infiltrated Anu's cult, intent on releasing Nylonathatep for their own purposes, and that the Falchion could not control the creature, let alone banish it, because the missing jewel prevented this. With Two-Conkers's help, Lewton recovers the jewel, and searches for Carlotta, who disappeared with the Falchion. Tracking her down, he finds her in a heated argument with Horst, who threatens to kill her for the relic, forcing him to kill the troll; Carlotta reluctantly gives him the Falchion in return, and allows him to hand her to the Watch for her crimes. With the Falchion restored by the missing jewel, Lewton defeats Nylonathatep with the help of a flying machine created by inventor Leonard da Quirm, saving the city.

In the aftermath, Lewton advises Ilsa to leave with Two-Conkers, knowing her husband is not safe in Ankh-Morpork, and watches as the pair leave on the flying machine, while he remarks to Gaspode how the two of them make a "beautiful friendship". The dog merely tells him not to push his luck with that idea.

Development

Perfect Entertainment had enjoyed a working relationship with Terry Pratchett and the Discworld licence from as early as 1993, collaborating closely to develop their first two Discworld games, Discworld (1995) and Discworld II (1996).[12][13] Discworld Noir was developed for Windows 95 and Windows 98.[4] GT Interactive were chosen as publisher due to their strong US presence, as the first two Discworld games had done relatively poorly in America.[14]

Chris Bateman, who had worked on Discworld II in a non-lead role, originally suggested using Teppic (the protagonist of Pyramids) as a lead character, though Pratchett disliked the idea.[15][16] Pratchett sent the developers a story outline and the first draft of the script, wanting a detective story set in Ankh-Morpork. The idea for a film noir theme specifically came from the developers.[17] Bateman wrote the ultimate script, which was then edited by Pratchett.[16] The script was the first one Bateman had written for a video game.[15] With each Discworld game Pratchett became less and less involved,[17] in Noir mainly being involved during the beginning and end of development.[16]

The game uses pre-rendered 3D models. Real-time 3D models were unfeasible for the period, as the developers needed the characters to have facial expressions and so likely few people would have computers powerful enough to run the game.[14] A full 3D game would have required simplification of the characters.[1] Utilising some 3D, however, allowed them to explore more with shadow and fog.[14] The backgrounds in the game remained 2D.[5]

Most of the voice acting was done by four actors: Rob Brydon, Kate Robbins, Robert Llewelyn, and Nigel Planer.[11] There was one less voice actor in Noir than in Discworld II; however, the heavy amount of dialogue in the game led to more reuse of voice actors in comparison.[16] Audio director Rob Lord also provided additional voices.[11] Robbins, voice actress for every female character in the game, finished her lines in a one-day session.[15] Brydon, who voiced the player character, took a "grueling" week to complete his lines, with the game's main delivery of important information being Lewton's hardboiled monologues.[15] Paul Weir created the soundtrack for the game.[14][16] Weir studied most of the noir films Discworld Noir drew on.[14]

After the release of Discworld Noir for the PC, Perfect Entertainment folded, leaving them unable to patch the game.[4] The company briefly resurfaced as "Teeny Weeny Games", and under this name the game was ported to the PlayStation. The PlayStation version has a lower resolution to the PC game and, in order to fit the game onto one disc (as opposed to the three discs of the PC version), compresses the game's sound and videos.[4] A port for the Dreamcast was in development, but never released.[citation needed]

As a result of the closure of GT Interactive, the game was never released outside of Europe.[4][18]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Discworld Noir received generally positive reviews upon its release. Marek Bronstring, writing for Adventure Gamer, rated Noir 4/5 stars and recommended buying the game.[25] Gordon Barrick gave the game 8/10.[9] PC Zone gave the game a positive review,[2] at the time ranking it as their sixth top adventure game.[26] Just Adventure's Tom Houston rated the game A−.[27] PC Gamer UK's Jonathan Davies gave the game a 74% quality rating.[22] Another reviewer for Just Adventure, Jenny Guenther, gave the game a C+, particularly criticising the game's bugs.[28]

The game's atmosphere was praised. Barrick praised the graphics and music for their part in creating the atmosphere, calling the backgrounds "detailed and beautifully rendered" and the saying the music underscored the game with "originality and style".[9] This praise was echoed by PC Zone, drawing notice to the shadows, lighting and fog, and calling the visuals "the perfect companions to an excellent soundtrack".[2] David Wildgoose, writing for PC PowerPlay, noted the "dark and seedy atmosphere", crediting "enticing visuals and a very cool soundtrack".[23] Guenther liked the music, giving the game's sound an A, but criticised the "broken-record-skipping" effect that seemed to get worse as the game went on.[28] The music and its effect on atmosphere was likewise praised by Houston.[27] Reviewing the French translation of the game, JeuxVideo.com's Kornifex praised the game's effective use of rain and its cinematic quality.[29] A second JeuxVideo.com review, however, criticised the scarcity of music and sound effects, though said what music there was brought "a semblance of atmosphere".[30]

The large amount of dialogue was criticised. PC Zone called the dialogue "generally interesting enough" to watch, but sometimes felt it could be too much.[2] The length of the conversations were one reason Tom Houston lowered the grade for Noir's gameplay to a C,[27] a complaint similarly raised by Guenther, who gave the gameplay a D.[28] Reaction to the humour of the game was similarly mixed. Wildgoose felt the developers "tried too hard to make every character and every situation funny", resulting in jokes that fell flat and a level of humour "only sporadically maintained".[23] Bronstring called the game generally amusing, but felt it "very tiresome" at times where it lasted too long.[20] Rose commented, "the dialogue is suitably authentic and funny in that slightly irritating I-know-it's-funny way that Pratchett writes",[21] while Davies criticised the game for not living up to Pratchett's humour.[22]

Bronstring felt the voices sounded "artificial", placing the blame on either poor editing of the various sound sources or a lack of variety in the four voice actors.[25] Barrick, however, praised the voice actors, feeling that every line came across "convincingly".[9] Guenther found the British attempts to imitate foreign accents funny, but nonetheless praised the voice acting.[28]

Retrospective

In a retrospective review in 2002, Bronstring maintained his original rating of 4/5 stars.[20] A 2011 retrospective by Eurogamer's John Walker called it "surprisingly poorly structured", and noted a lack of puzzles. Walker still admitted a "fondness" for the game, however, comparing it favourably to the company's first two Discworld adventure games, noting a lack of "grating knowing tweeness" and an ability to be genuinely funny.[5] In 2011, Adventure Gamers would go on to place it at number 27 in their "Top 100 All-time Adventure Games" list, giving credit to its innovative notepad mechanism, which would become a common element in adventure games.[31] Walker later listed it at number 20 in "The 25 Best Adventure Games Ever Made", praising the voice cast.[32] PC Gamer's Richard Cobbett placed it as 25 in a similar list, commenting "the third Discworld game finally shed its predecessors' fixation with being as much Python as Pratchett".[33] Andy Kelly, also writing for PC Gamer, called it one of the 20 best detective games. Kelly commented: "Its shadowy, rain-soaked setting, Ankh-Morpork, is brilliantly atmospheric, and it manages to both mock film noir and be a loving homage to it."[34]

Dave Gilbert called Discworld Noir one of his favourite adventure games, and called it "one of [his] biggest inspirations". Gilbert would eventually create the "Oz noir" adventure game Emerald City Confidential (2009).[35] Kate Berens and Geoff Howard's The Rough Guide to Videogaming includes Discworld Noir as one of its recommended games. Noting the heavy number of conversations, they felt the game played "more like an interactive novel at times" but praised the dialogue and called Ankh-Morpork "beautifully rendered".[36]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Croft, Martin (10 March 1999). "Discworld Noir Preview". GameSpot UK. http://www.gamespot.co.uk/pc.gamespot/adventure/discn_uk/preview.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Discworld Noir". PC Zone (London, England: Dennis Publishing Ltd.) (79): 80–81. August 1999. https://archive.org/details/PC_Zone_79_August_1999. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Nutt, Christian (12 September 2007). "AGDC: Bateman Reveals The 'Temperament Theory'". Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160922192224/http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/106421/AGDC_Bateman_Reveals_The_Temperament_Theory.php.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Kalata, Kurt (10 April 2010). "Discworld". Hardcore Gaming 101. p. 2. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160330091117/http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/discworld/discworld2.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Walker, John (11 September 2011). "Retrospective: Discworld Noir". Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160415033836/http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2011-09-11-retrospective-discworld-noir-article.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cobbett, Richard (3 June 2016). "The best adventure games on PC". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160616142215/http://www.pcgamer.com/the-25-best-adventure-games/.

- ↑ Nettelbeck, Joachim (July 1999). "Discworld Noir" (in de). Power Play (Germany): 102–105.

- ↑ Mądrzak, Andrzej (14 November 2011). "Top 10 Zawód: Detektyw" (in Polish). gry.wp.pl. http://gry.wp.pl/artykul/felieton,top-10-zawod-detektyw,6374,3.html.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Barrick, Gordon (30 July 1999). "Discworld Noir Review". http://www.gamespot.co.uk/pc.gamespot/adventure/discn_uk/review.html.

- ↑ Bateman, Chris (January 1999). "Feature: Interview with Perfect Entertainment - Part 2". Discworld Monthly (21). Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150214073531/http://www.discworldmonthly.co.uk/dwm0021.php. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Discworld Noir Manual. GT Interactive. 1999. pp. 29–30.

- ↑ "Welcome to Discworld!". The One (EMAP Images): 14. September 1993. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170319082623/https://archive.org/details/theone-magazine-59. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ "Interview with Perfect Entertainment". 15 September 1996. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160618204924/http://www.csoon.com/issue17/interv.htm.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Bronstring, Marek (20 April 1999). "Interviews - Discworld Noir". http://www.adventuregamer.com/features/interviews/discworld.shtml.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Bateman, Chris (26 March 2008). "My Words in Other Voices". Only a Game. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161008085218/http://onlyagame.typepad.com/only_a_game/2008/03/my-words-in-oth.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Bronstring, Barek (7 February 2003). "Chris Bateman on Discworld Noir". Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160420124318/http://www.adventuregamers.com/articles/view/17586.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Terry Pratchett Interview". 1999. http://gamespot.co.uk/pc.gamespot/features/discnoir_uk/.

- ↑ "Chris Bateman on Discworld Noir". 7 February 2003. http://www.adventuregamers.com/article/id,204.

- ↑ "Discworld Noir". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160414163533/http://www.gamerankings.com/pc/576124-discworld-noir/index.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Bronstring, Marek (6 February 2002). "Discworld Noir review". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160324121353/http://www.adventuregamers.com/articles/view/17579.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Rose, Paul (January 2000). "Discworld Noir". Official UK PlayStation Magazine (54): 117. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160417125741/http://read.oldgamemags.com/Sony%20PlayStation/PlayStation%20Official%20Magazine%20%28UK%29/PlayStation%20%282000-01%29%20054%20%28Future%29.pdf/. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Davies, Jonathan (September 1999). "Discworld Noir". PC Gamer UK (79).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Wildgoose, David (August 1999). "Discworld Noir". PC PowerPlay (Australia: Next Publishing) (39): 80–82. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160417120426/http://read.oldgamemags.com/IBM-PC/PC%20Powerplay/PCPowerplay-039.pdf/. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Barrick, Gordon (July 30, 1999). "Discworld Noir Review". PC Gaming World. Archived from the original on 15 August 2000. https://web.archive.org/web/20000815235702/http://www.gamespot.co.uk/pc.gamespot/adventure/discn_uk/review.html.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bronstring, Marek (27 July 1999). "Reviews - Discworld Noir". Archived from the original. Error: If you specify

|archiveurl=, you must also specify|archivedate=. https://web.archive.org/web/20000817024417/http://www.adventuregamer.com/reviews/misc/noir.shtml. - ↑ "Top 100". PC Zone (London, England: Dennis Publishing Ltd.) (80): 120–123. September 1999. https://archive.org/details/PC_Zone_80_September_1999. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Houston, Tom. "Review: Discworld Noir". Archived from the original. Error: If you specify

|archiveurl=, you must also specify|archivedate=. https://web.archive.org/web/20081228080934/http://www.justadventure.com/reviews/DWN/Discworld_Noir_Review2.shtm. - ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Guenther, Jenny. "Review: Discworld Noir". Just Adventure. Archived from the original. Error: If you specify

|archiveurl=, you must also specify|archivedate=. https://web.archive.org/web/20010718110742/http://www.justadventure.com/reviews/DWN/Discworld_Noir_Review.shtm. - ↑ Kornifex (21 July 1999). "Test: Discworld Noir" (in French). Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160508052234/http://www.jeuxvideo.com/articles/0000/00000047_test.htm.

- ↑ "Test: Discworld Noir" (in French). 27 April 2000. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160508220904/http://www.jeuxvideo.com/articles/0000/00000618_test.htm.

- ↑ "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". 30 December 2011. p. 16. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150911060932/http://www.adventuregamers.com/articles/view/18643/page16/.

- ↑ Walker, John (12 June 2015). "The 25 Best Adventure Games Ever Made". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160322040026/https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2015/06/12/best-adventure-games/3/.

- ↑ Cobbett, Richard (23 October 2014). "The 25 best adventure games". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160329130248/http://www.pcgamer.com/the-25-best-adventure-games/.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (30 July 2015). "The 20 best detective games". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160402042357/http://www.pcgamer.com/the-best-detective-games/.

- ↑ Gilbert, Dave; Gonzalez, Francisco (29 September 2014). "Wadjet Eye's Dave Gilbert and Francisco Gonzalez Talk Adventure". Hardcore Gamer. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160701100614/http://www.hardcoregamer.com/2014/09/29/wadjet-eyes-dave-gilbert-and-francisco-gonzalez-talk-adventure-2/108090/.

- ↑ Berens, Kate; Howard, Geoff (2002). The Rough Guide to Videogaming (2nd ed.). London: Rough Guides. pp. 49–51. ISBN 9781858289106.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|