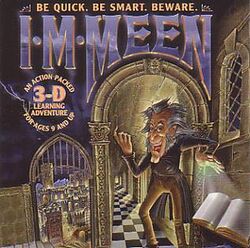

Software:I.M. Meen

| I.M. Meen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Animation Magic |

| Publisher(s) | Simon & Schuster Interactive |

| Producer(s) | Dale DeSharone Igor Razboff |

| Designer(s) | Matthew Sughrue |

| Programmer(s) | Kirill Agheev Dima Barmenkov Misha Chekmarev Linde Dynneson Misha Figurin John O'Brien |

| Artist(s) | Masha Kolesnikova (character design) |

| Writer(s) | Matthew Sughrue |

| Composer(s) | Anthony Trippi |

| Platform(s) | DOS |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Educational, first-person shooter, fantasy |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

I.M. Meen is a 1995 fantasy educational game for DOS to teach grammar to children.[1][2] It is named for its villain, Ignatius Mortimer Meen, a "diabolical librarian" who lures young readers into an enchanted labyrinth and imprisons them with monsters and magic.[2]

The goal of the game is to escape the labyrinth and free other children. This is accomplished by "shooting spiders and similar monsters" and deciphering grammatical mistakes in scrolls written by Meen.[3]

The game was created by Russo-American company Animation Magic, which also animated the CD-i games Link: The Faces of Evil and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon.[3][4] Peter Berkrot provided the voices of I.M. Meen and his gnome henchman Gnorris.

Plot

In the introduction cutscene, Ignatius Mortimer Meen introduces himself via song as an evil magician who despises children and learning. He sings about creating a magical book that sucks children into an abysmal labyrinth upon reading it.

At the end of the musical number, the book sucks two children into an underground labyrinth, where they are found by monstrous guardians and locked into cells. Players play as two children named Scott and Katie, who are trapped inside this labyrinth. Gnorris, a gnome who has betrayed I.M. Meen, helps the two escape and, after sending them to rescue the other children, presents a magic orb so he can contact the player at any time. He gives hints as the game progresses and warns whenever a boss is nearby.

The player travels through the labyrinth, defeating the monsters and rescuing the children, causing the labyrinth's condition to rapidly deteriorate. The player must eventually confront I.M. Meen himself and defeat him using Writewell's Book of Better Grammar, which he has stolen and hidden in the labyrinth. After his defeat, the magician vows revenge and disappears, declaring that he will return and make good on his promise.

Gameplay

The game contains 36 levels[2] with nine locations, including a tower, a dungeon, sewers, caves, catacombs, hedgerow mazes, castles, laboratories, and libraries. The player must rescue all the children on each level to get to the next one, which is done by fixing grammar mistakes in various scrolls. In every fourth level, the player must defeat a boss monster, otherwise known as one of I.M. Meen's special pets, to advance to a new area. There are items in the labyrinth that can be used to help the player defeat the various monsters that dwell in the labyrinth, as well as help them out in other ways. The player has an Agility Meter, similar to a health meter that, when it runs out, takes the player back to the beginning of the level and removes all items collected on that level. Near the end of the game, the player must defeat I.M Meen himself, who can only be harmed by the Writewell's Book of Better Grammar (other weapons have no effect on him at all). Defeating him and solving the last scroll wins the game.

Reception

| Reception | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| ||||||

The Contra Costa Times gave the game a positive review, calling it "the first computer game for young children to use the same fast 3-D graphics found in Doom" and praising it for its educational themes.[7] Brad Cook of Allgame thought that the game's graphics and sound were well-executed, and thought that the game was well-developed for its time, but concluded his review by saying, "Since this program set out first and foremost to be an educational product, I'll have to give it a low mark because it simply fails to do that, despite how well-done the rest of it is" and gave the game two stars out of five.[5]

Legacy

A 1996 sequel to the game was made, titled Chill Manor, featuring a story about I.M. Meen's presumed wife, Ophelia Chill, who obtains the Book of Ages and tears out all the pages, allowing her to rewrite history. Meen appears at the game's ending to rescue Ophelia after she is tied to a chair. I.M. Meen, as well as Sonic's Schoolhouse and 3D Dinosaur Adventure: Save the Dinosaurs, has been named as one of the "creepy, bad" inspirations for the indie game Baldi's Basics in Education and Learning.[8][9]

Beginning circa 2005, I. M. Meen's animated cutscenes became a major source material for YouTube Poops, among cutscenes from other Animation Magic games including Link: The Faces of Evil and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon.[10]

References

- ↑ "Learn Math and the Meaning of Fear in Baldi's Basics -" (in en-US). 2018-06-05. https://games.mxdwn.com/news/learn-math-and-the-meaning-of-fear-in-baldis-basics/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Media, Working Mother (December 1995) (in en). Working Mother. Working Mother Media. https://books.google.com/books?id=P_avy2YSswkC&dq=%22i.+m.+meen%22&pg=PT72.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cobbett, Richard (2020-06-20). "Crapshoot: I.M. Meen, a grammar game with the creepiest villain" (in en). PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/saturday-crapshoot-i-m-meen/.

- ↑ Cobbett, Richard (2017-08-23). "The weirdest shooters of the '90s" (in en). PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/the-weirdest-shooters-of-the-90s/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cook, Brad. "I.M. Meen review". Allgame. http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=15837&tab=review.

- ↑ "Í.M. Meen - The Free Library". http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Capitol+Multimedia,+Inc.+to+develop+three+titles+for+Simon+%26+Schuster...-a017717744.

- ↑ "Fun, educational game lets kids explore their 'meen' streak". Contra Costa Times. 1995-08-11. http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=CC&s_site=contracostatimes&p_multi=CC&p_theme=realcities&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=1063F954008B063F&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM.

- ↑ Conville, Caitlyn (2018-06-15). "'Baldi's Basics' Brings Nostalgia for Millennial Gamers" (in en-US). https://studybreaks.com/culture/baldis-basics/.

- ↑ Potvin, James (2022-10-17). "10 Most Memorable Viral Horror Games, Ranked" (in en-US). https://screenrant.com/best-memorable-viral-horror-games-ranked/.

- ↑ "Inside YouTube Poop, the nonsensical genre that invented meme culture on the internet" (in en). https://screenshot-media.com/culture/internet-culture/what-is-youtube-poop/.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|