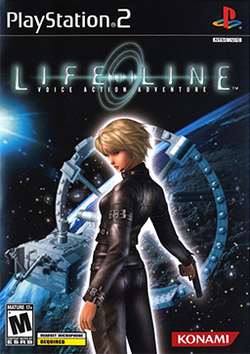

Software:Lifeline (video game)

| Lifeline | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Director(s) | Manabu Nishizawa |

| Producer(s) | Yasuhide Kobayashi Takafumi Fujisawa |

| Designer(s) | Manabu Nishizawa |

| Programmer(s) | Takayuki Wakimura |

| Artist(s) | Taku Nakamura Benimaru Watari |

| Composer(s) | Shingo Okumura |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 2 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Adventure game, survival horror |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

Lifeline, released in Japan as Operator's Side (オペレーターズサイド Operētāzu Saido), is a 2003 survival horror adventure video game developed and published by Sony Computer Entertainment (and published by Konami in North America) for the PlayStation 2. Set in the near future aboard a space hotel attacked by unidentified monsters, the game follows the player as they direct cocktail waitress Rio Hohenheim to safety while searching for the player's girlfriend Naomi as well as the source of the monster infestation.

Lifeline's defining aspect is its voice user interface: the vast majority of gameplay is conducted by using the PlayStation 2's microphone to issue commands, which are interpreted by the game via speech recognition to control Rio and dictate her movements and actions.

Lifeline was released on January 30, 2003 in Japan and March 2, 2004 in North America; in Japan, it was optionally sold alongside the PlayStation 2 headset. It received generally mixed reviews, with praise for its innovation and potential but criticism for the low reliability of its speech recognition. However, Lifeline still sold well enough to be rereleased in Japan on September 25, 2003 under Sony's The Best budget range, and the game has maintained somewhat of a cult following over the years since its release for its innovative gameplay and the depth of its voice mechanics.

Gameplay

Lifeline is a survival horror adventure game where the player issues orders to Rio Hohenheim as she attempts to escape a monster-infested space station. The standout feature of Lifeline is its voice user interface in which the player speaks into their microphone to command Rio. The player never directly controls Rio, nor any other character, at any point in the game; rather, they are required to tell her what to do at any given time, such as directing her where to go, advising her to examine or use objects, or ordering her what to aim for during a battle with a monster. Such spoken commands include "run", "stop", "dodge", and "turn left", among many others (approximately 500 commands exist), which prompt Rio to perform specific actions and progress throughout the game. To issue commands, the player must hold the input mic button (the O button on the DualShock controller) before speaking.

The player can access various menus which provide inventory insertions, detailed maps, and commands to unlock multiple parts of the station. By using the menus available, the player directs Rio in combat, solves puzzles, examines and interfaces with objects of note, and interacts with NPCs. During a battle, the player can order Rio to maneuver within the battle space, shift focus to certain enemies, or target specific body parts. Combat perspectives switch between first-person and that of nearby cameras, with the latter more suitable for encounters with numerous foes. Plot interactions are followed through at the player's general discretion, with Rio inquiring about which path of action to take.

In regular situations, the player can converse with Rio, with the latter sometimes inquiring about it. The player can play games with her (e.g. challenge each other to tongue twisters, with Rio receiving health if successfully completed), ask her to do sexual things (e.g. to "do a sexy pose", which she may or may not follow through with), or simply engage in small talk with her (e.g. suggest she eat food or shoot at a static object; she may do so, or more commonly explain her rationale for not doing so). There are also a few Easter egg conversations; for instance, Rio can ask about the player's girlfriend's name, and react with surprise if the player gives her own name or the name of Rio's voice actor.

Plot

In 2029, the player character, an unnamed young man only referred to as the "Operator", and his girlfriend Naomi (Sayaka in the Japanese version) attend a Christmas party aboard the Japan Space Line's Space Station Hotel, a large space station orbiting Earth serving as a premium hotel for the ultra-rich. Suddenly, unidentified alien-like monsters attack the festivities, killing most of the guests and staff and separating Naomi and the Operator, who is trapped in the Space Station Hotel's main control room. From the control room, the Operator, having full access to the Space Station Hotel's mechanisms and cameras, comes into contact with Rio Hohenheim (voiced by Mariko Suzuki in the Japanese version and Kristen Miller in the English version), a cocktail waitress who survived the initial attack after being locked in a holding cell for her own safety and is attempting to contact the control room. Communicating with Rio through her headset, the Operator agrees to help her and assists her through the perils of the station, while also attempting to find Naomi and investigate the source of the monsters.

After fighting their way through monsters, clearing difficult puzzles, and coming across both fellow survivors and a paramilitary rescue force, Rio and the Operator learn that the monsters are not extraterrestrials, but rather horribly-mutated humans resulting from an attempt to recreate the philosopher's stone that, instead of healing someone, cursed them to remain alive and drastically mutated them beyond recognition. They also learn that the stone needed to be created in a zero-gravity environment and that the station is now on a collision course with Earth to return the stone for use as a weapon. Along the way, Rio meets with her father, now a disillusioned, disembodied brain in a jar incapable of recognizing her, while the Operator reunites with Naomi, who has since been mutated but is still holding on to her humanity; both die after meeting the pair.

In the end, Rio and the Operator destroy the lead monster, and they meet in person for the first time. Now adamant to destroy the stone, Rio and the Operator set the Space Station Hotel to self-destruct and manage to reach an escape pod in time. Rio thanks the Operator as the escape pod starts a descent towards Earth.

Development

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lifeline received "mixed" reviews according to video game review aggregator Metacritic.[1] The voice command system, though the game's primary feature, has often been noted to be its game's weak point, due to inaccurate actions taken when commands are given, and the basic sense of conversation and directions reduced to simple verbs and nouns, particularly when in the course of solving many of the game's puzzles.

IGN noted that while the voice recognition system is "quite deep", the player "will need to practice enunciating regular words and learning the speed at which the game best responds", and "might spend five minutes trying to get the right word to simply inspect a worthless book."[9]

In 2008, Game Informer listed Lifeline among the worst horror games of all time.[13] In 2009, GamesRadar included it among the games "with untapped franchise potential", commenting: "While this frustrated many PS2 owners, it made others feel more attached to the characters. Improvements in headset and voice-recognition technology make a franchise more viable on today’s systems."[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Lifeline for PlayStation 2 Reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/game/lifeline-2004/.

- ↑ Edge staff (May 2004). "Lifeline". Edge (136): 106.

- ↑ EGM staff (April 2004). "Lifeline". Electronic Gaming Monthly (177): 118.

- ↑ Mason, Lisa (March 2004). "Lifeline". Game Informer (131): 102. http://www.gameinformer.com/Games/Review/200403/R04.0317.0957.52122.htm. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ↑ The D-Pad Destroyer (March 2004). "LifeLine Review for PS2 on GamePro.com". GamePro: 72. http://www.gamepro.com/sony/ps2/games/reviews/34511.shtml. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ↑ Davis, Ryan (March 2, 2004). "Lifeline Review". http://www.gamespot.com/reviews/lifeline-review/1900-6090485/.

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin (March 2, 2004). "GameSpy: Lifeline". GameSpy. http://ps2.gamespy.com/playstation-2/lifeline/499730p1.html.

- ↑ Bedigian, Louis (March 8, 2004). "Lifeline - PS2 - Review". GameZone. http://www.gamezone.com/reviews/lifeline_ps2_review.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Perry, Douglass C. (March 3, 2004). "Lifeline". http://www.ign.com/articles/2004/03/03/lifeline.

- ↑ "Lifeline". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. April 2004.

- ↑ Lopez, Miguel (March 23, 2004). "'LifeLine' (PS2) Review". X-Play. http://www.g4techtv.com/xplay/features/493/LifeLine_PS2_Review.html.

- ↑ Saltzman, Marc (March 25, 2004). "'LifeLine' players give a shout out". The Cincinnati Enquirer. http://www.cincinnati.com/freetime/games/reviews/032504_lifeline.html.

- ↑ "The Wrong Kind of Scary: Worst Horror Games Ever". Game Informer (186): 121. October 2008.

- ↑ 123 games with untapped franchise potential , GamesRadar US, April 30, 2009

External links

- Short description: Video game database

Logo since March 2014 | |

Screenshot  Frontpage as of April 2012[update] | |

Type of site | Gaming |

|---|---|

| Available in | English |

| Owner | Atari SA |

| Website | mobygames |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Optional |

| Launched | January 30, 1999 |

| Current status | Online |

MobyGames is a commercial website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes nearly 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] The site is supported by banner ads and a small number of people paying to become patrons.[2] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It is currently owned by Atari SA.

Content

The database began with games for IBM PC compatibles. After two years, consoles such as the PlayStation, were added. Older console systems were added later. Support for arcade video games was added in January 2014 and mainframe computer games in June 2017.[3]

Edits and submissions go through a leisurely verification process by volunteer "approvers". The approval process can range from immediate (minutes) to gradual (days or months).[4] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copyediting.[5]

Registered users can rate and review any video game. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own subforum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999 by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, then joined by David Berk 18 months later, three friends since high school.[6] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience.

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[7] This was announced to the community post factum and a few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.

On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San-Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[8] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel.[9]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[10] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[11][12]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ "MobyGames Stats". https://www.mobygames.com/moby_stats.

- ↑ "MobyGames Patrons". http://www.mobygames.com/info/patrons.

- ↑ "New(ish!) on MobyGames – the Mainframe platform.". Blue Flame Labs. 18 June 2017. http://www.mobygames.com/forums/dga,2/dgb,3/dgm,237200/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/32856/Report_MobyGames_Acquired_By_GameFly_Media.php.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/207882/Game_dev_database_MobyGames_getting_some_TLC_under_new_owner.php.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site’s Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

|

Warning: Default sort key "Lifeline (Video Game)" overrides earlier default sort key "Mobygames".

|