Software:Michigan: Report from Hell

| Michigan: Report from Hell | |

|---|---|

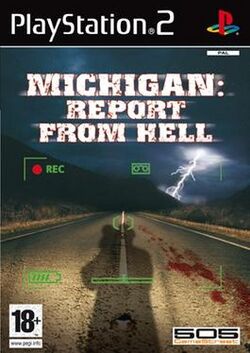

European box art | |

| Developer(s) | Grasshopper Manufacture |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Akira Ueda |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) | Tetsuya Nakazawa |

| Artist(s) |

|

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) |

|

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 2 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Michigan: Report from Hell[lower-alpha 1] is a video game developed by Grasshopper Manufacture. It was published in Japan by Spike in 2004, and in Europe by 505 GameStreet the following year. Alternately described as adventure and survival horror, the game follows a news crew investigating Chicago after a mist covers the city following a plane crash in Lake Michigan. Gameplay features the player as a cameraman guiding the reporter through different scenarios, with the ending influenced by what the player captures on film.

The game was developed during a period when Grasshopper Manufacture was staying in business through contract work. Company founder Goichi Suda created the initial concept, and acted as a producer. The director was Akira Ueda, while the music was composed by Masafumi Takada. The Japanese version included promotional material featuring Taiwanese model Yinling. The game was not released in North America due to its minimal gameplay. Michigan: Report from Hell saw generally mixed reviews, with several Western journalists noting its unique premise but faulting its gameplay and presentation.

Gameplay

Michigan: Report from Hell is a video game−alternately described as adventure in Japan and survival horror in Western reports−where players take on the role of a television crew cameraman.[1][2][3] The game is split into levels dubbed "Scenarios", with the player able to save between each scenario.[4] The player as camerman being limited in interaction to moving through the city streets and building interiors, focusing the camera on different in-game elements, giving instructions to the reporter, solving puzzles found during exploration, and kicking objects such as doors. Some enemies can be killed by solving an environmental puzzle, while others must be avoided by sending warnings to the reporter.[4][5][6]

The reporter can die during a level, which skips a section of the game and replaces them with one of seven other reporters.[6][7] The camerman has a limited amount of film for each level, which is used to capture different elements or scenes.[4] These scenes fills up different points related to "Suspense", "Erotic" and "Immoral", with the final point total for each altering the ending.[7] The game ends if the camerman is killed, or the camera runs out of film, forcing the player to restart from the beginning of a scenario.[3][4][8]

Synopsis

After a plane crashes into Lake Michigan, a fog covers the nearby city of Chicago . Media company ZakaTV sends in a crew to cover the incident; lead reporter Pamela Martel, a rookie cameraman, and sound engineer Brisco. Upon arrival, the crew are attacked by monstrous creatures that have killed most of the city's population. Pamela is soon killed and reanimated as a monster. Joined by a new reporter, the crew learn that the fog and monsters were created by a virus designed by unhinged scientist Dr. O'Conner. Intended as a weapon against enemies of the United States, and developed in collusion with ZakaTV, the virus escaped containment following the plane crash and infected the city's population. The group find O'Conner, who transforms willingly after revealing the existence of a vaccine in the city.

Failing to find the vaccine, the crew attempt to escape via an airport, running into a mentally-impaired man who is revealed to be O'Conner's initial test subject for the virus. Upon being killed, the fog vanishes and the rest of the monsters die. On orders from the military, the crew reach a lighthouse evacuation point, but before they are rescued Brisco mutates into a monster and kills himself to keep them safe. The ending shows the cameraman making a final video; in three endings he tries to reveal the truth behind the incident and is shot by an unseen assassin, while in a fourth he is corrupted and claims responsibility for the disaster. Secret movies found through the game reveal potential reporter Paula Orton as the assassin, silencing anyone who uncovers ZakaTV's involvement.

Development

Michigan was developed by Grasshopper Manufacture, then known for their work on The Silver Case and Flower, Sun, and Rain.[9] During the early 2000s, Grasshopper Manufacture undertook contract work for other publishers to stay solvent during a difficult period, with Michigan being one of those projects.[10][11] Spike's president Mitsutoshi Sakurai contacted company founder Goichi Suda about working together on a game project.[9][12] Suda created a game concept around the theme of "mist", taking inspiration from Stephen King's The Mist.[12] Initially planned to be a game where players explored a mist-covered Chicago and with the mist itself being the threat, the team were unable to make it work, and during a meeting Suda and Sakurai reworked the design.[12] This reworking resulted in the inclusion of monsters to make the game more frightening, and the mechanic of guiding a female reporter as a cameraman.[9][12]

Due to his commitment directing Killer7, he worked on Michigan as an uncredited producer;[12][13][14] the credited co-producers were Maki Kimura and Yasu Iizuka of Spike.[14][15][16] The director was Akira Ueda, who had previously directed Shining Soul and its sequel Shining Soul II.[17][14] The scenario was co-written by Nobuhiko Sagara and Ren Yamazaki, who worked on later Grasshopper Manufacture projects including the No More Heroes series.[14][18][19] The staff included main programmer Tetsuya Nakazawa, art director Tatsuji Fujita, and character designer Katsuyoshi Fukamachi.[14] The music was co-composed by Masafumi Takada and Jun Fukuda in their first collaboration, going on to work on Killer7.[20] Suda remembered production as difficult and having "twists and turns".[21] Morality was described as a core gameplay theme, with the team wanting the player's moral choices to alter the game's outcome.[22] Michigan is one of the few Grasshopper Manufacture games to include horror, as Suda is not a fan of the genre.[23] Speaking in 2018, Suda felt the company was too inexperienced to properly realise his design goals.[12]

Release

Michigan was announced in January 2004.[24] The Japanese version included promotional material featuring Taiwanese model Yinling,[25] with New Game Plus content featuring Yinling as an in-game character.[7] The game was released in Japan on 5 August the same year, titled Michigan.[1] A strategy guide was published by SoftBank Creative on 16 August,[26] and a soundtrack album was published by Scitron Digital Contents on 20 October.[27]

Michigan was released in Europe, something that Suda was not aware of initially.[28] The game was published in the region by 505 GameStreet on 30 September 2005 as Michigan: Report from Hell.[2][7] It was dubbed into English, and featured subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian and German.[2][3] The European release cut Yinling's content, and had a number of bugs.[3] In an interview with Suda for Gamasutra, journalist Brandon Sheffield revealed he had proposed a North American release to a publisher, and been told that Sony's North American branch blocked it due to its minimal gameplay content.[22] Both Suda and Sakurai have voiced their willingness to revisit Michigan in some form, with Suda stating he would like to either remake the game or create something new around the gameplay concept.[10][22][29]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

During 2004, the game was among the top five hundred best-selling titles in Japan according to Media Create, selling over 31,600 copies.[32] Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu gave it a score of 30 points out of 40.[31] Michigan: Report from Hell received "mixed" reviews according to the review aggregation website Metacritic with a score of 53 points out of 100 based on four reviews.[30]

Justin Speer, writing for Xplay, noted its unconventional mechanics and presentation, but felt uncomfortable with its erotic elements and either poor implementation of its mechanics or points when the control is taken from the player without warning.[5] In an import playtest for IGN, Anoop Gantayat echoed these complaints, and did not recommend the game despite being interested in the concept.[6] In a hands-on preview article, British magazine Official UK PlayStation 2 Magazine noted the unusual premise, but failed both the gameplay experience and the lack of advertised erotic elements, summing it up as "a watered-down" survival horror with "ropey" voice-acting and a "terrible" plot.[33]

John Sczepaniak of Hardcore Gaming 101, writing in 2012, felt that the game was bad due to its unpolished mechanics and lack of interactivity, but nevertheless called it a "genuinely unique experiment, since there really is nothing else even remotely like it in the grand history of video games".[3] Jeff Cork, writing for Game Informer for the website's "Replay" video features in 2014, felt the game could have become a cult classic if released in North America.[34] Nick Thorpe of Retro Gamer highlighted the game's unique approach to the genre and passive gameplay style, noting that it was becoming a collector's item due to its rarity and Suda's growing reputation.[35]

In a feature on Grasshopper Manufacture, 1UP.com's Ray Barnholt was not very positive about the game, noting both its erotic elements and limited interactivity.[36] Michigan was featured in a 2011 Game Informer article on games not released in North America, with writer Joe Juba comparing it to other Grasshopper Manufacture games that featured unique style and presentation despite lacking engaging gameplay.[37] In a small piece on Suda's history, gaming magazine Play noted Michigan as having an "interesting twist" on the horror genre.[38]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Spike. http://www.spike.co.jp/game/details.php?id=23&gid=ps2. - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "505 Games - PlayStation 2 -Page 3". 505 Games. http://505gamestreet.it/products.htm?con=PS2&pag=3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Szczepaniak, John (12 October 2012). "Michigan: Report From Hell". http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/michigan-report-from-hell/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Grasshopper Manufacture (5 August 2004) (in ja) (Instruction manual) (Japanese ed.). Spike.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Speer, Justin (27 September 2005). "Michigan Import Review". Archived from the original. Error: If you specify

|archiveurl=, you must also specify|archivedate=. https://web.archive.org/web/20051210215519/http://www.g4tv.com/xplay/features/52672/Michigan_Import_Review.html. - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Gantayat, Anoop (17 August 2004). "Import Playtest: Michigan". https://www.ign.com/articles/2004/08/17/import-playtest-michigan.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Grasshopper Manufacture. https://www.grasshopper.co.jp/projects/michigan.html. - ↑ Razak, Matthew (24 October 2009). "Suda wants to remake Michigan: Report from Hell". https://www.destructoid.com/suda-wants-to-remake-michigan-report-from-hell/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ciolek, Todd (21 July 2015). "The Art of Japanese Video Game Design With Suda51". http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interview/2015-07-21/the-art-of-japanese-video-game-design-with-suda51/.90633.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kemps, Heidi (28 September 2016). "Interview: Suda51 of Grasshopper Manufacture". http://gaming.moe/?p=2116.

- ↑ Noclip (July 3, 2020). Suda51 (Killer7 / No More Heroes) Breaks Down His Design Philosophy (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 (in ja). PIE Corporation. 30 June 2018. ISBN 978-4-8356-3857-7.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". Kojima Productions. Konami. 5 October 2009. http://www.kjp.konami.jp/gs/hideoblog/2006/10/000182.html. - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Grasshopper Manufacture (29 September 2005). Michigan: Report from Hell. PlayStation 2. 505 GameStreet. Scene: Credits.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). 2008. https://dengekionline.com/pr/spike/bioshock/interview.html. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Spike. http://www.spike.co.jp/company/company/data.html. - ↑ Robinson, Andy (22 May 2006). "Suda 51: Contact established". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original. Error: If you specify

|archiveurl=, you must also specify|archivedate=. https://web.archive.org/web/20070204052415/http://www.computerandvideogames.com/article.php?id=140354. Retrieved 28 February 2017. - ↑ Napolitano, Jayson (13 May 2010). "No More Heroes 2 Interview with Jun Fukuda and Nobuhiko Sagara". http://www.originalsoundversion.com/no-more-heroes-2-interview-with-jun-fukuda-and-nobuhiko-sagara/.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). 21 January 2022. https://cgworld.jp/interview/202201-grasshopper.html. - ↑ "Creators". Too Kyo Games. https://tookyogames.jp/english/#0.

- ↑ (in ja)Famitsu. 13 July 2015. https://www.famitsu.com/news/201507/13083176.html. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Sheffield, Brandon (20 October 2009). "Interview: Suda51 Talks Theme, Style And Innovation". http://www.gamasutra.com/php-bin/news_index.php?story=25587.

- ↑ Arnold, Cory (7 October 2016). "Talking about the future with Suda51". https://www.destructoid.com/talking-about-the-future-with-suda51-391418.phtml.

- ↑ "Killer 7 director Gouichi Suda at work on new PS2 title". 15 January 2004. https://www.gamespot.com/articles/killer-7-director-gouichi-suda-at-work-on-new-ps2-title/1100-6086567/.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). 25 June 2004. https://dengekionline.com/data/news/2004/6/25/d40b8c30dcb8e7e7c2d5a8376b465871.html. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). 2004. https://nlab.itmedia.co.jp/games/ps2/2004/michigan/first/index.html. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). Scitron Digital Contents. http://www.webcity.jp/ds/detail.php?pid=SCDC-00378. - ↑ "Interview: A chat with Suda 51". Computer and Video Games (Future plc). 15 March 2008. http://www.computerandvideogames.com/article.php?id=184821. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Ike, Sato (28 March 2018). "Spike Chunsoft CEO Talks About Bringing More Visual Novels And Japanese Games To The West". http://www.siliconera.com/2018/03/28/spike-chunsoft-ceo-talks-bringing-visual-novels-japanese-games-west/.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Michigan (ps2: 2004): Reviews". http://www.metacritic.com/games/platforms/ps2/michigan.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 (in ja)Famitsu (Enterbrain) (817). 30 July 2004.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ja). http://geimin.net/da/db/2004_ne_fa/index.php. - ↑ "Hands On - Michigan: Report from Hell". Official UK PlayStation 2 Magazine (Future plc) (63): 50. September 2005.

- ↑ Cork. Jeff (30 August 2014). "Replay – Michigan: Report From Hell". Game Informer. https://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2014/08/30/replay-michigan-report-from-hell.aspx. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Thorpe, Nick (17 May 2018). "Minority Report - PlayStation 2". Retro Gamer (Future plc) (181): 93.

- ↑ Barnholt, Ray (18 October 2008). "Formula 51 - A look at Suda 51". p. 4. http://www.1up.com/features/following-grasshopper.

- ↑ Juba, Joe (18 August 2011). "Top 10 Import-Only Oddities". Game Informer. http://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2011/08/18/import-only-oddities.aspx. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Flashback: A brief history of Goichi Suda". Play (Imagine Publishing) (197): 12. November 2010.

Notes

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|