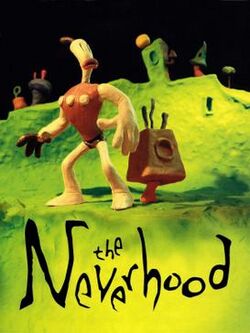

Software:The Neverhood

| The Neverhood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) |

|

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Doug TenNapel Mark Lorenzen |

| Artist(s) | Mike Dietz Ed Schofield Mark Lorenzen Stephen Crow |

| Writer(s) | Dale Lawrence Mark Lorenzen Doug TenNapel |

| Composer(s) | Terry Scott Taylor |

| Engine | The Neverhood, Inc. |

| Platform(s) | Microsoft Windows, PlayStation |

| Release | Microsoft Windows PlayStation

|

| Genre(s) | Point-and-click adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Neverhood (released in Japan as Klaymen Klaymen: The Mystery of Neverhood) is a 1996 point-and-click adventure video game developed by The Neverhood, Inc. and published by DreamWorks Interactive for Microsoft Windows. The game follows the adventure of a claymation character named Klaymen as he discovers his origins and his purpose in a world made entirely out of clay. When the game was originally released, it was unique in that all of its animation was done entirely in claymation, including all of the sets. The gameplay consists mostly of guiding the main character Klaymen around and solving puzzles to advance. Video sequences help advance the plot. In addition to being unique, The Neverhood aimed at being quirky and humorous, as is evident by the characters, the music, and the plot sequence. The game has garnered a cult following. It received a sequel in 1998, Skullmonkeys, which was a platform game, abandoning the adventure format of the original. Armikrog was later released as a spiritual successor to the game, developed by many members of the same team.

Gameplay

The Neverhood is a point-and-click adventure game which emphasizes the solving of puzzles through character action rather than inventory usage.[2] Klaymen must use the available environment in order to advance in the game, with the standard inventory being quasi-absent. There are possible gameovers if the player is not careful enough, with one where the game cannot be restored from a previous save and must be restarted.

Plot

The titular Neverhood is a surreal landscape dotted with buildings and other hints of life, all suspended above an endless void. However, the Neverhood itself is strangely deserted, with its only inhabitants being Klaymen (the main protagonist and player character), Willie Trombone (a dim individual who assists Klaymen in his travels), Klogg (the game's antagonist who resembles a warped version of Klaymen), and various fauna that inhabit the Neverhood (most infamously the 'weasels', monstrous, crablike creatures that pursue Klaymen and Willie at certain points in the game). Much of the game's background information is limited to the 'Hall Of Records' which is notorious for its length, taking several minutes to travel from one end of the hall to the other.

The game begins with Klaymen waking up in a room and exploring the Neverhood, collecting various discs appearing to contain a disjointed story narrated by Willie (which Klaymen can view through various terminals scattered throughout the land). As Klaymen travels the Neverhood, he occasionally crosses paths with Willie, who agrees to help him in his journey, while Klogg spies on them from afar. Eventually, Klaymen's quest directs him to Klogg's castle, and for this Klaymen enlists the help of Big Robot Bil, a towering automaton and a friend of Willie's. As Bil (with Klaymen and Willie on board) marches to Klogg's castle, Klogg unleashes his guardian, the Clockwork Beast, to intercept Bil. The two giants clash and Bil proves victorious, but as he forces open the castle door for Klaymen to enter, Klogg gravely injures Bil by firing a cannon at him. Klaymen manages to get in, but Bil loses his footing and falls into the void with Willie still inside.

Alone in Klogg's castle, Klaymen finds the last of Willie's discs, revealing the full context of his tale: The Neverhood itself is the creation of a godlike being named Hoborg, who created the Neverhood in the hopes of making himself happy. Realizing that he was still alone, Hoborg created himself a companion by planting a seed into the ground, which grew into Klogg. As Hoborg welcomed Klogg to the Neverhood, the latter tried to take Hoborg's crown, which Hoborg forbade Klogg from doing. Envious, Klogg managed to steal Hoborg's crown, rendering Hoborg inert in the process, and the crown's energies disfigured Klogg. With Hoborg lifeless, any further development of the Neverhood ground to a halt. Having witnessed this, Willie (himself and Bil being creations of Hoborg's brother Ottoborg) discovered that Hoborg was about to plant a seed to create another companion. Willie took the seed and planted it far away from Klogg, with Willie hoping that whoever grew from the seed would defeat Klogg: That seed in turn grew into Klaymen.

The story ends with Willie giving Klaymen the throne room key through the terminal screen, hoping that Klaymen knows what to do once he confronts Klogg. Afterwards, Klaymen manages to enter the throne room, with Klogg and a motionless Hoborg waiting for him. Klogg tries to dissuade Klaymen from reviving Hoborg by tempting him with Hoborg's crown.

From here, the player may choose to take up Klogg's offer or take the crown to revive Hoborg:

- If the player chooses to take the crown for himself, Klogg gloats at his apparent victory, only for the now-villainous Klaymen, crowned and disfigured (similarly to Klogg), to instantly overpower Klogg and declare himself the new ruler of the Neverhood.

- If the player chooses to revive Hoborg, Klaymen distracts Klogg and manages to put the crown atop Hoborg's head, reviving him. As Hoborg thanks Klaymen, Klogg attempts to ambush them both, only to set off his own cannon which blasts him out of the castle and into the void. Returning to the building where Klaymen first started, Hoborg continues populating the Neverhood and orders a celebration when he is finished. However, Klaymen remains sorrowful over the loss of Willie and Bil, and Hoborg decides to use his powers to save Willie and Bil (to Klaymen's delight), and the game ends with Hoborg telling Klaymen "Man, things are good".

Development

Doug TenNapel came up with the idea of a plasticine world in 1988, creating approximately 17 structures.[3] Due to his dissatisfaction with the way David Perry ran Shiny Entertainment, TenNapel left the company in 1995. Two weeks later he announced at E3 that he started his own company, The Neverhood, Inc., which consisted of a number of people who worked on the Earthworm Jim game and its sequel.[4] Steven Spielberg's DreamWorks Interactive, which had recently started, needed fresh and unusual projects and TenNapel approached Spielberg with the idea of a claymation game, with Spielberg accepting it for publication.[3] The Neverhood, Inc. made a deal with DreamWorks Interactive and Microsoft, and the game went for development. According to the developers, creating the game's characters and scenery used up over three tons of clay.[2] The Neverhood was shown at E3 1996 under the title The Neverhood: A Curious Wad of Klay Finds His Soul.[5]

After a year of work, The Neverhood was finally released to the public in 1996.[6] The game elements were shot entirely on beta versions of the Minolta RD-175, making The Neverhood the first stop-motion production to use consumer digital cameras for professional use.

Soundtrack

The game's soundtrack was composed and performed by Daniel Amos frontman Terry Scott Taylor and went on to win GMR magazine's "Best Game Music of the Year" award. Tom Clancy's video game composer Bill Brown called The Neverhood Soundtrack, "The Best of any of them (video game soundtracks)."[7]

Ports and legacy

A PlayStation port of the game titled Klaymen Klaymen: The Mystery of the Neverhood was made and released to Japanese audiences only.[8] The game had some minor changes to the PC version such as longer loading times between rooms and the removal of The Hall of Records area.[9] The Japanese release of Skullmonkeys, in turn, was titled Klaymen Klaymen 2.[10]

In June 2011, it was announced via Facebook and Twitter that some of the original developers of The Neverhood were negotiating for exclusive rights to release the game on modern platforms such as iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad, Android phones, Android tablets and Windows Phones.[11][12]

As official support had ceased, e.g. updates for modern OS and hardware, a fan group created new compatibility fixes in the "Neverhood restoration project" in 2013.[13]

On July 21, 2014, ScummVM version 1.7.0 was released by the ScummVM project which added support for The Neverhood, allowing it to run on many supported platforms including Linux, OS X, Windows and Android OS.[14]

Reception

Sales

According to Leslie Helm of the Los Angeles Times, The Neverhood "won rave reviews" but was commercially unsuccessful.[15] In early 1997, that paper's Greg Miller reported that the game's "sales have been slow and [it] isn't even carried by all of the largest stores, including Target". This came at a time when big-box stores were increasingly important for securing sales, as many specialized video game retailers had closed due to competition with these outside companies.[16] By August 1997, The Neverhood had sold 37,000 copies in the United States.[15] Sales in the region had risen to 41,073 copies by April 1999, a figure that CNET Gamecenter's Marc Saltzman called "embarrassing".[17]

The Neverhood's total sales ultimately surpassed 50,000 copies, and "hundreds of thousands" of OEM copies were purchased by Gateway and pre-installed on its line of computers, according to Mike Dietz.[18] It also received a huge fan base in Russia and Iran as a result of the massive bootleg copying and distribution of pre-installed games on computers.[19]

Critical reviews

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Next Generation critic was pleased with both the visual style (which he said is essentially unprecedented on PC) and the execution of the graphics, but found the game is held back by unexciting puzzles and a generally slow pace.[21] GameSpot likewise stated that the game has endearing visuals but is held back by the puzzles. However, rather than being dull, they judged the puzzles to be unfairly difficult and frustrating, remarking that "Clues are so abstract they will lead you to despair."[23] GamePro contradicted, "While some of the puzzles are perplexing, none of them have solutions so obscure that you'll burst a blood vessel trying to solve them." However, they agreed that the graphics and the personality of the characters are the highlights of the game.[34] Weekly Famitsu gave the PlayStation version a score of 29 out of 40.[8]

The Neverhood was named the best adventure game of 1996 by Computer Games Strategy Plus and CNET Gamecenter,[29][30] and was nominated for the latter publication's overall "Game of the Year" prize, which ultimately went to Quake. Gamecenter's editors wrote that it "went beyond anything seen so far in this genre".[30] The game also won the 1996 "Special Award for Artistic Achievement" from Computer Gaming World, whose staff called it "the coolest-looking game of the year."[31] While The Neverhood was nominated for the Computer Game Developers Conference's "Best Animation" Spotlight Award,[32] it lost in this category to Tomb Raider.[33]

Animation Magazine's film festival "World Animation Celebration" awarded the game "Best Animation Produced for Game Platforms" in 1997.[35]

In 2011, Adventure Gamers named The Neverhood the 35th-best adventure game ever released.[36]

Sequels

A sequel to The Neverhood was released in 1998 for the PlayStation, entitled Skullmonkeys. It was not a point-and-click adventure game like the first installment, but rather a platform game.

Following the sequel, another Japanese PlayStation game set in the Neverhood universe called Klaymen Gun-Hockey was made. A Japan-only sports action game, it was based on the characters of the Neverhood, but was not developed by the designers of the original games; it also did not feature the previous releases' distinctive Claymation design techniques. The game is a variation on air hockey, only played with guns instead of mallets. It was developed and published by Riverhillsoft, the publisher of Japanese releases of the Neverhood series.

Klaymen is featured as a secret fighter for the PlayStation game BoomBots, also developed by The Neverhood, Inc.

On March 12, 2013, TenNapel announced that he had partnered with former Neverhood and Earthworm Jim artists/animators Ed Schofield and Mike Dietz of Pencil Test Studios to develop a "clay and stop-motion animated point and click adventure game".[37][38] While stating that the game would not be a sequel to The Neverhood, TenNapel reiterated that the game would consist of his unique art style and sense of humor, and have an original soundtrack by Terry Scott Taylor. The game was titled Armikrog, which was released on September 30, 2015.[39][40]

Return to the Neverhood

In 2012, the authors of the original Neverhood released a musical novel, Return to the Neverhood. The story and soundtrack were written by Terry Scott Taylor, and the illustrations were drawn by Doug TenNapel.[41][42]

Cancelled film

On June 25, 2007, Variety reported that one of Frederator Films' first projects would be a claymation feature film adaptation based on The Neverhood. Doug TenNapel, the creator of the video game, signed on to write and direct the film.[43] However, the movie was cancelled due to a lack of funding.[44]

References

- ↑ "Online Gaming Review". February 27, 1997. http://www.ogr.com/news/news1096.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Neverhood: A Curious Wad of Klay Finds his Soul". GamePro (IDG) (96): 54. September 1996.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Review of The Neverhood Chronicles". Game Revolution. June 5, 2004. http://www.gamerevolution.com/review/pc/the-neverhood-chronicles.

- ↑ "Welcome To The Neverhood". Awn.com. http://www.awn.com/mag/issue2.9/2.9pages/2.9neverhood.html.

- ↑ Staff (June 1, 1996). "E3 Adventure & Role Playing Games". Computer Games Strategy Plus. http://www.cdmag.com:80/adventure_vault/e3_adventure/page1.html.

- ↑ "GameSpot:Video Games PC Xbox 360 PS3 Wii PSP DS PS2 PlayStation 2 GameCube GBA PlayStation 3". Replay.waybackmachine.org. May 16, 2008. http://www.gamespot.com/features/neverhood/interview/tn_02.html.

- ↑ "Terry Scott Taylor". Daniel Amos band website. http://www.danielamos.com/tst/tst.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "クレイマン・クレイマン 〜ネバーフッドの謎〜 [PS / ファミ通.com"]. https://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?a=page_h_title&title_id=17041.

- ↑ "The Neverhood". May 2, 2010. http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/neverhood-the/.

- ↑ "Skullmonkeys". May 2, 2010. http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/skullmonkeys/.

- ↑ Neverhood MobileAboutTimelineAbout. "Neverhood Mobile - Résumé". Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/NeverhoodMobile?sk=info.

- ↑ "Klaymen (@NeverhoodMobile) op Twitter". Twitter.com. https://twitter.com/NeverhoodMobile.

- ↑ Neverhood restoration project on sourceforge.net (accessed August 2015)

- ↑ "ScummVM 1.7.0 "The Neverrelease" is out!". ScummVM. July 21, 2014. http://scummvm.org/news/20140721/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Helm, Leslie (August 18, 1997). "Have CD-ROMances Run Their Course?". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-aug-18-fi-23584-story.html.

- ↑ Miller, Greg (March 3, 1997). "Myst Opportunities: Game Makers Narrow Their Focus to Search for the Next Blockbuster". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-03-03-fi-34360-story.html.

- ↑ Saltzman, Marc (June 4, 1999). "The Top 10 Games That No One Bought". CNET Gamecenter. http://www.gamecenter.com/Features/Exclusives/Notbought/index.html.

- ↑ Zellmer, Dylan (June 18, 2013). "Exclusive – The Neverhood's Mike Dietz 'The Industry Is Stuck In A Rut'". iGame Responsibly. http://www.igameresponsibly.com/2013/06/18/exclusive-the-neverhoods-mike-dietz-the-industry-is-stuck-in-a-rut/.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine{{cbignore} b|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFDj-YsZODU&t=11m50s |title=Funny Interview with Doug Tennapel! Armikrog on Kickstarter! |date=June 26, 2013 |publisher=WelovegamesTV |access-date=October 6, 2013}}

- ↑ Hedstrom, Kate (December 1996). "Klay Time". Computer Gaming World (149): 304.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "The Neverhood". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (24): 268, 272. December 1996.

- ↑ Davies, Jonathan. "Pastic". PC Gamer UK (36). http://www.pcgamer.co.uk/games/gamefile_review_page.asp?item_id=1229.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hutsko, Joe (October 24, 1996). "The Neverhood Review". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/the-neverhood/reviews/the-neverhood-review-2543926/. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ Vaughn, Todd (December 1996). "Reviews; The Neverhood Chronicles". PC Gamer US 3 (12): 258.

- ↑ Yans, Cindy (1996). "The Neverhood". Computer Games Strategy Plus. http://www.cdmag.com/articles/004/143/neverhood_review.html.

- ↑ "DPSソフトレビュー The Deeper Part 2: クレイマン・クレイマン 〜ネバーフットの謎〜" (in ja). Dengeki PlayStation (MediaWorks) 74: 106. May 8-22, 1998. https://archive.org/details/play-station-vol.-74-1998-5-8-22/page/108/mode/1up.

- ↑ Cheng, Kipp (November 29, 1996). "PC Game Review: 'The Neverhood'". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,295189,00.html. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ Mooney, Shane (February 4, 1997). "Looking for Adventure?". PC Magazine 16 (3): 366, 368.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Computer Games Strategy Plus announces 1996 Awards". Computer Games Strategy Plus. March 25, 1997. http://www.cdmag.com/news/0325971.html.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 The Gamecenter Editors. "The Gamecenter Awards for 96". CNET Gamecenter. http://www.gamecenter.com:80/Features/Exclusives/Awards96/indexa.html.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Staff (May 1997). "The Computer Gaming World 1997 Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World (154): 68–70, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Staff (April 15, 1997). "And the Nominees Are...". Next Generation. http://www.next-generation.com:80/news/041597e.chtml.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Spotlight Awards Winners Announced for Best Computer Games of 1996" (Press release). Santa Clara, California: Game Developers Conference. April 28, 1997. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011.

- ↑ Major Mike (December 1996). "PC GamePro Review Win 95: The Neverhoo". GamePro (IDG) (99): 95.

- ↑ "WAC Awards for 1997". https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0213117/awards?ref_=tt_awd.

- ↑ AG Staff (December 30, 2011). "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". Adventure Gamers. http://www.adventuregamers.com/articles/view/18643.

- ↑ "The Official Neverhood Facebook Page". Facebook.com. https://www.facebook.com/TheNeverhoodGame.

- ↑ "The Neverhood Game Will Get a Worthy Successor". Mountspace.net. http://www.mountspace.net/eng/news/the-neverhood-game-will-get-a-worthy-successor-2013-03-22.

- ↑ "The Neverhood creator working on a new claymation point-and-click adventure". Eurogamer.net. March 15, 2013. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2013-03-15-the-neverhood-creator-working-on-a-new-claymation-point-and-click-adventure.

- ↑ "Neverhood creator developing a full, stop-motion animated adventure game". PCgamer.com. March 14, 2013. http://www.pcgamer.com/2013/03/14/neverhood-stop-motion-adventure/.

- ↑ Return to the Neverhood - Daniel Amos

- ↑ Return To Neverhood - Promo video

- ↑ McNary, Dave (June 26, 2007). "Toon trio starts Frederator" (in en-US). Variety. https://variety.com/2007/digital/markets-festivals/toon-trio-starts-frederator-1117967622/.

- ↑ "Some sad news". July 6, 2010. https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/neverhoodcommunity/some-sad-news-t634.html.

External links

- Official site (archived)

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

- Hardcore Gaming 101: The Neverhood / Klaymen Klaymen

- The Neverhood on IMDb

- The Neverhood TV

- All About the NeverhoOd

Warning: Default sort key "Neverhood" overrides earlier default sort key "Mobygames".

|