Spherical law of cosines

In spherical trigonometry, the law of cosines (also called the cosine rule for sides[1]) is a theorem relating the sides and angles of spherical triangles, analogous to the ordinary law of cosines from plane trigonometry.

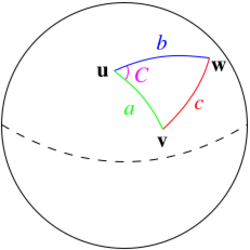

Given a unit sphere, a "spherical triangle" on the surface of the sphere is defined by the great circles connecting three points u, v, and w on the sphere (shown at right). If the lengths of these three sides are a (from u to v), b (from u to w), and c (from v to w), and the angle of the corner opposite c is C, then the (first) spherical law of cosines states:[2][1]

Since this is a unit sphere, the lengths a, b, and c are simply equal to the angles (in radians) subtended by those sides from the center of the sphere. (For a non-unit sphere, the lengths are the subtended angles times the radius, and the formula still holds if a, b and c are reinterpreted as the subtended angles). As a special case, for C = π/2, then cos C = 0, and one obtains the spherical analogue of the Pythagorean theorem:

If the law of cosines is used to solve for c, the necessity of inverting the cosine magnifies rounding errors when c is small. In this case, the alternative formulation of the law of haversines is preferable.[3]

A variation on the law of cosines, the second spherical law of cosines,[4] (also called the cosine rule for angles[1]) states:

where A and B are the angles of the corners opposite to sides a and b, respectively. It can be obtained from consideration of a spherical triangle dual to the given one.

Proofs

First proof

Let u, v, and w denote the unit vectors from the center of the sphere to those corners of the triangle. The angles and distances do not change if the coordinate system is rotated, so we can rotate the coordinate system so that is at the north pole and is somewhere on the prime meridian (longitude of 0). With this rotation, the spherical coordinates for are where θ is the angle measured from the north pole not from the equator, and the spherical coordinates for are The Cartesian coordinates for are and the Cartesian coordinates for are The value of is the dot product of the two Cartesian vectors, which is

Second proof

Let u, v, and w denote the unit vectors from the center of the sphere to those corners of the triangle. We have u · u = 1, v · w = cos c, u · v = cos a, and u · w = cos b. The vectors u × v and u × w have lengths sin a and sin b respectively and the angle between them is C, so

using cross products, dot products, and the Binet–Cauchy identity

Third proof

The following proof relies on the concept of quaternions and is based on a proof given in Brand:[5] Let u, v, and w denote the unit vectors from the center of the unit sphere to those corners of the triangle. We define the quaternion u = (0, u) = 0 + uxi + uyj + uzk. The quaternion u is used to represent a rotation by 180° around the axis indicated by the vector u. We note that using −u as the axis of rotation gives the same result, and that the rotation is its own inverse. We also define v = (0, v) and w = (0, w).

We compute the product of quaternions, which also gives the composition of the corresponding rotations:

- q = vu−1 = (v)(−u) = (−(v · −u), v × −u) = (u · v, u × v) = (cos a, w′ sin a)

where (f, g) represents the real (scalar) and imaginary (vector) parts of a quaternion, a is the angle between u and v, and w′ = (u × v) / |u × v| is the axis of the rotation that moves u to v along a great circle. Similarly we define:

- r = wv−1 = (v · w, v × w) = (cos b, u′ sin b).

- s = uw−1 = (w · u, w × u) = (cos c, v′ sin c)

The quaternions q, r, and s are used to represent rotations with axes of rotation w′, u′, and v′, respectively, and angles of rotation 2a, 2b, and 2c, respectively. (Because these are double angles, each of q, r, and s represents two applications of the rotation implied by an edge of the spherical triangle.)

From the definitions, it follows that

- srq = uw−1wv−1vu−1 = 1,

which tells us that the composition of these rotations is the identity transformation. In particular, rq = s−1 gives us

- (cos b, u′ sin b) (cos a, w′ sin a) = (cos c, −v′ sin c).

Expanding the left-hand side, we obtain

Equating the real parts on both sides of the identity, we obtain

Because u′ is parallel to v × w, w′ is parallel to u × v = −v × u, and C is the angle between v × w and v × u, it follows that . Thus,

Rearrangements

The first and second spherical laws of cosines can be rearranged to put the sides (a, b, c) and angles (A, B, C) on opposite sides of the equations:

Planar limit: small angles

For small spherical triangles, i.e. for small a, b, and c, the spherical law of cosines is approximately the same as the ordinary planar law of cosines,

To prove this, we will use the small-angle approximation obtained from the Maclaurin series for the cosine and sine functions:

Substituting these expressions into the spherical law of cosines nets:

or after simplifying:

The big O terms for a and b are dominated by O(a4) + O(b4) as a and b get small, so we can write this last expression as:

History

Various trigonometric equations equivalent to the spherical law of cosines were used in the course of solving astronomical problems by medieval Islamic astronomers al-Khwārizmī (9th century) and al-Battānī (c. 900), Indian astronomer Nīlakaṇṭha (15th century), and Austrian astronomer Georg von Peuerbach (15th century) but none of them treated it as a general method for solving spherical triangles.[6] For example, al-Khwārizmī calculated the azimuth of the Sun in terms of its altitude , terrestrial latitude , and ortive amplitude (angular distance between due East and the Sun's rising place on the horizon) as .[7] (See Horizontal coordinate system.)

The spherical law of cosines appeared as an independent trigonometrical identity for solving spherical triangles in Peuerbach's student Regiomontanus's De triangulis omnimodis (unfinished at Regiomontanus's death in 1476, published posthumously 1533), a foundational work for European trigonometry and astronomy which comprehensively described how to solve plane and spherical triangles. Regiomontanus used nearly the modern form, but written in terms of the versine, , rather than the cosine,[8]

Mathematical historians have speculated that Regiomontanus may have adapted the result from specific astronomical examples in al-Battānī's Kitāb az-Zīj aṣ-Ṣābi’, which was published in Latin translation annotated by Regiomontanus in 1537.

See also

- Half-side formula

- Hyperbolic law of cosines

- Solution of triangles

- Spherical law of sines

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 W. Gellert, S. Gottwald, M. Hellwich, H. Kästner, and H. Küstner, The VNR Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics, 2nd ed., ch. 12 (Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, 1989).

- ↑ Romuald Ireneus 'Scibor-Marchocki, Spherical trigonometry, Elementary-Geometry Trigonometry web page (1997).

- ↑ R. W. Sinnott, "Virtues of the Haversine", Sky and Telescope 68 (2), 159 (1984).

- ↑ Reiman, István (1999). Geometria és határterületei. Szalay Könyvkiadó és Kereskedőház Kft.. p. 83.

- ↑ Brand, Louis (1947). "§186 Great Circle Arccs". Vector and Tensor Analysis. Wiley. pp. 416–417. https://archive.org/details/vectortensoranal00branrich/page/416/.

- ↑ Van Brummelen, Glen (2012). Heavenly mathematics: The forgotten art of spherical trigonometry. Princeton University Press. p. 98. Bibcode: 2012hmfa.book.....V.

- ↑ Van Brummelen, Glen (2009). "Early Spherical Astronomy: Graphical Methods and Analemmas". The Mathematics of the Heavens and the Earth: The Early History of Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. § 4.7, Template:Pgs. ISBN 978-0-691-12973-0.

- ↑ Van Brummelen, Glen (2009). "From Ptolemy to Triangles: John of Gmunden, Peurbach, Regiomontanus". The Mathematics of the Heavens and the Earth: The Early History of Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. § 6.5, Template:Pgs. ISBN 978-0-691-12973-0.

he:טריגונומטריה ספירית#משפט הקוסינוסים

|