Zero-knowledge proof

In cryptography, a zero-knowledge proof (also known as a ZK proof or ZKP) is a protocol in which one party (the prover) can convince another party (the verifier) that some given statement is true, without conveying to the verifier any information beyond the mere fact of that statement's truth.[1] The intuition behind the nontriviality of zero-knowledge proofs is that it is trivial to prove possession of the relevant information simply by revealing it; the hard part is to prove this possession without revealing this information (or any aspect of it whatsoever).[2]

In light of the fact that one should be able to generate a proof of some statement only when in possession of certain secret information connected to the statement, the verifier, even after having become convinced of the statement's truth by means of a zero-knowledge proof, should nonetheless remain unable to prove the statement to further third parties.

Zero-knowledge proofs can be interactive, meaning that the prover and verifier exchange messages according to some protocol, or noninteractive, meaning that the verifier is convinced by a single prover message and no other communication is needed. In the standard model, interaction is required, except for trivial proofs of BPP problems.[3] In the common random string and random oracle models, non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs exist. The Fiat–Shamir heuristic can be used to transform certain interactive zero-knowledge proofs into noninteractive ones.[4][5][6]

Abstract examples

The red card proof

One example of a math-free zero knowledge proof is if Peggy wants to prove to Victor that she has drawn a red card from a standard deck of 52 playing cards, without revealing which specific red card she holds. Victor observes Peggy draw a card at random from the shuffled deck, but she keeps the card face-down so he cannot see it.

To prove her card is red without revealing its identity, Peggy takes the remaining 51 cards from the deck and systematically shows Victor all 26 black cards (the 13 spades and 13 clubs) one by one, placing them face-up on the table. Since a standard deck contains exactly 26 red cards and 26 black cards, and Peggy has demonstrated that all the black cards remain in the deck, Victor can conclude with certainty that Peggy's hidden card must be red.

This proof is zero-knowledge because Victor learns only that Peggy's card is red, but gains no information about whether it is a heart or diamond, or which specific red card she holds. The proof would be equally convincing whether Peggy held the Ace of Hearts or the Two of Diamonds. Furthermore, even if the interaction were recorded, the recording would not reveal Peggy's specific card to future observers, maintaining the zero-knowledge property.

If Peggy was lying and actually held a black card, she would be unable to produce all 26 black cards from the remaining deck, making deception impossible. This demonstrates the soundness of the proof system. This type of physical zero-knowledge proof using standard playing cards belongs to a broader class of card-based cryptographic protocols that allow participants to perform secure computations using everyday objects.[7]

Where's Wally

Another well-known example of a zero-knowledge proof is the "Where's Wally" example. In this example, the prover wants to prove to the verifier that they know where Wally is on a page in a Where's Wally? book, without revealing his location to the verifier.[8]

The prover starts by taking a large black board with a small hole in it, the size of Wally. The board is twice the size of the book in both directions, so the verifier cannot see where on the page the prover is placing it. The prover then places the board over the page so that Wally is in the hole.[8]

The verifier can now look through the hole and see Wally, but cannot see any other part of the page. Therefore, the prover has proven to the verifier that they know where Wally is, without revealing any other information about his location.[8]

This example is not a perfect zero-knowledge proof, because the prover does reveal some information about Wally's location, such as his body position. However, it is a decent illustration of the basic concept of a zero-knowledge proof.

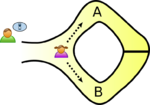

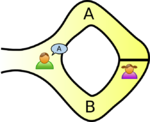

The Ali Baba cave

There is a well-known story presenting the fundamental ideas of zero-knowledge proofs, first published in 1990 by Jean-Jacques Quisquater and others in their paper "How to Explain Zero-Knowledge Protocols to Your Children".[9] The two parties in the zero-knowledge proof story are Peggy as the prover of the statement, and Victor, the verifier of the statement.

In this story, Peggy has uncovered the secret word used to open a magic door in a cave. The cave is shaped like a ring, with the entrance on one side and the magic door blocking the opposite side. Victor wants to know whether Peggy knows the secret word; but Peggy, being a very private person, does not want to reveal her knowledge (the secret word) to Victor or to reveal the fact of her knowledge to the world in general.

They label the left and right paths from the entrance A and B. First, Victor waits outside the cave as Peggy goes in. Peggy takes either path A or B; Victor is not allowed to see which path she takes. Then, Victor enters the cave and shouts the name of the path he wants her to use to return, either A or B, chosen at random. Providing she really does know the magic word, this is easy: she opens the door, if necessary, and returns along the desired path.

However, suppose she did not know the word. Then, she would only be able to return by the named path if Victor were to give the name of the same path by which she had entered. Since Victor would choose A or B at random, she would have a 50% chance of guessing correctly. If they were to repeat this trick many times, say 20 times in a row, her chance of successfully anticipating all of Victor's requests would be reduced to 1 in 220, or 9.54 × 10−7.

Thus, if Peggy repeatedly appears at the exit Victor names, then he can conclude that it is extremely probable that Peggy does, in fact, know the secret word.

One side note with respect to third-party observers: even if Victor is wearing a hidden camera that records the whole transaction, the only thing the camera will record is in one case Victor shouting "A!" and Peggy appearing at A or in the other case Victor shouting "B!" and Peggy appearing at B. A recording of this type would be trivial for any two people to fake (requiring only that Peggy and Victor agree beforehand on the sequence of As and Bs that Victor will shout). Such a recording will certainly never be convincing to anyone but the original participants. In fact, even a person who was present as an observer at the original experiment should be unconvinced, since Victor and Peggy could have orchestrated the whole "experiment" from start to finish.

Further, if Victor chooses his As and Bs by flipping a coin on-camera, this protocol loses its zero-knowledge property; the on-camera coin flip would probably be convincing to any person watching the recording later. Thus, although this does not reveal the secret word to Victor, it does make it possible for Victor to convince the world in general that Peggy has that knowledge—counter to Peggy's stated wishes. However, digital cryptography generally "flips coins" by relying on a pseudo-random number generator, which is akin to a coin with a fixed pattern of heads and tails known only to the coin's owner. If Victor's coin behaved this way, then again it would be possible for Victor and Peggy to have faked the experiment, so using a pseudo-random number generator would not reveal Peggy's knowledge to the world in the same way that using a flipped coin would.

Peggy could prove to Victor that she knows the magic word, without revealing it to him, in a single trial. If both Victor and Peggy go together to the mouth of the cave, Victor can watch Peggy go in through A and come out through B. This would prove with certainty that Peggy knows the magic word, without revealing the magic word to Victor. However, such a proof could be observed by a third party, or recorded by Victor and such a proof would be convincing to anybody. In other words, Peggy could not refute such proof by claiming she colluded with Victor, and she is therefore no longer in control of who is aware of her knowledge.

Two balls and the colour-blind friend

Imagine Victor is red-green colour-blind (while Peggy is not) and Peggy has two balls: one red and one green, but otherwise identical. To Victor, the balls seem completely identical. Victor is skeptical that the balls are actually distinguishable. Peggy wants to prove to Victor that the balls are in fact differently coloured, but nothing else. In particular, Peggy does not want to reveal which ball is the red one and which is the green.

Here is the proof system: Peggy gives the two balls to Victor and he puts them behind his back. Next, he takes one of the balls and brings it out from behind his back and displays it. He then places it behind his back again and then chooses to reveal just one of the two balls, picking one of the two at random with equal probability. He will ask Peggy, "Did I switch the ball?" This whole procedure is then repeated as often as necessary.

By looking at the balls' colours, Peggy can, of course, say with certainty whether or not he switched them. On the other hand, if the balls were the same colour and hence indistinguishable, Peggy's ability to determine whether a switch occurred would be no better than random guessing. Since the probability that Peggy would have randomly succeeded at identifying each switch/non-switch is 50%, the probability of having randomly succeeded at all switch/non-switches approaches zero.

Over multiple trials, the success rate would statistically converge to 50%, and Peggy could not achieve a performance significantly better than chance. If Peggy and Victor repeat this "proof" multiple times (e.g. 20 times), Victor should become convinced that the balls are indeed differently coloured.

The above proof is zero-knowledge because Victor never learns which ball is green and which is red; indeed, he gains no knowledge about how to distinguish the balls.[10]

Definition

A zero-knowledge proof of some statement must satisfy three properties:

- Completeness: if the statement is true, then an honest verifier (that is, one following the protocol properly) will be convinced of this fact by an honest prover.

- Soundness: if the statement is false, then no cheating prover can convince an honest verifier that it is true, except with some small probability.

- Zero-knowledge: if the statement is true, then no verifier learns anything other than the fact that the statement is true. In other words, just knowing the statement (not the secret) is sufficient to imagine a scenario showing that the prover knows the secret. This is formalized by showing that every verifier has some simulator that, given only the statement to be proved (and no access to the prover), can produce a transcript that "looks like" an interaction between an honest prover and the verifier in question.

The first two of these are properties of more general interactive proof systems. The third is what makes the proof zero-knowledge.[11]

Zero-knowledge proofs are not proofs in the mathematical sense of the term because there is some small probability, the soundness error, that a cheating prover will be able to convince the verifier of a false statement. In other words, zero-knowledge proofs are probabilistic "proofs" rather than deterministic proofs. However, there are techniques to decrease the soundness error to negligibly small values (for example, guessing correctly on a hundred or thousand binary decisions has a 1/2100 or 1/21000 soundness error, respectively. As the number of bits increases, the soundness error decreases toward zero).

A formal definition of zero-knowledge must use some computational model, the most common one being that of a Turing machine. Let P, V, and S be Turing machines. An interactive proof system with (P,V) for a language L is zero-knowledge if for any probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) verifier there exists a PPT simulator S such that:

where View[P(x)↔(x,z)] is a record of the interactions between P(x) and V(x,z). The prover P is modeled as having unlimited computation power (in practice, P usually is a probabilistic Turing machine). Intuitively, the definition states that an interactive proof system (P,V) is zero-knowledge if for any verifier there exists an efficient simulator S (depending on ) that can reproduce the conversation between P and on any given input. The auxiliary string z in the definition plays the role of "prior knowledge" (including the random coins of ). The definition implies that cannot use any prior knowledge string z to mine information out of its conversation with P, because if S is also given this prior knowledge then it can reproduce the conversation between and P just as before. The definition given is that of perfect zero-knowledge. Computational zero-knowledge is obtained by requiring that the views of the verifier and the simulator are only computationally indistinguishable, given the auxiliary string.[12]

Practical examples

Discrete log of a given value

These ideas can be applied to a more realistic cryptography application. Peggy wants to prove to Victor that she knows the discrete logarithm of a given value in a given group.[13]

For example, given a value y, a large prime p, and a generator , she wants to prove that she knows a value x such that gx ≡ y (mod p), without revealing x. Indeed, knowledge of x could be used as a proof of identity, in that Peggy could have such knowledge because she chose a random value x that she did not reveal to anyone, computed y = gx mod p, and distributed the value of y to all potential verifiers, such that at a later time, proving knowledge of x is equivalent to proving identity as Peggy.

The protocol proceeds as follows: in each round, Peggy generates a random number r, computes C = gr mod p and discloses this to Victor. After receiving C, Victor randomly issues one of the following two requests: he either requests that Peggy discloses the value of r, or the value of (x + r) mod (p − 1).

Victor can verify either answer; if he requested r, he can then compute gr mod p and verify that it matches C. If he requested (x + r) mod (p − 1), then he can verify that C is consistent with this, by computing g(x + r) mod (p − 1) mod p and verifying that it matches (C · y) mod p. If Peggy indeed knows the value of x, then she can respond to either one of Victor's possible challenges.

If Peggy knew or could guess which challenge Victor is going to issue, then she could easily cheat and convince Victor that she knows x when she does not: if she knows that Victor is going to request r, then she proceeds normally: she picks r, computes C = gr mod p, and discloses C to Victor; she will be able to respond to Victor's challenge. On the other hand, if she knows that Victor will request (x + r) mod (p − 1), then she picks a random value r′, computes C′ ≡ gr′ · (gx)−1 mod p, and discloses C′ to Victor as the value of C that he is expecting. When Victor challenges her to reveal (x + r) mod (p − 1), she reveals r′, for which Victor will verify consistency, since he will in turn compute gr′ mod p, which matches C′ · y, since Peggy multiplied by the modular multiplicative inverse of y.

However, if in either one of the above scenarios Victor issues a challenge other than the one she was expecting and for which she manufactured the result, then she will be unable to respond to the challenge under the assumption of infeasibility of solving the discrete log for this group. If she picked r and disclosed C = gr mod p, then she will be unable to produce a valid (x + r) mod (p − 1) that would pass Victor's verification, given that she does not know x. And if she picked a value r′ that poses as (x + r) mod (p − 1), then she would have to respond with the discrete log of the value that she disclosed – but Peggy does not know this discrete log, since the value C she disclosed was obtained through arithmetic with known values, and not by computing a power with a known exponent.

Thus, a cheating prover has a 0.5 probability of successfully cheating in one round. By executing a large-enough number of rounds, the probability of a cheating prover succeeding can be made arbitrarily low.

To show that the above interactive proof gives zero knowledge other than the fact that Peggy knows x, one can use similar arguments as used in the above proof of completeness and soundness. Specifically, a simulator, say Simon, who does not know x, can simulate the exchange between Peggy and Victor by the following procedure. Firstly, Simon randomly flips a fair coin. If the result is "heads", then he picks a random value r, computes C = gr mod p, and discloses C as if it is a message from Peggy to Victor. Then Simon also outputs a message "request the value of r" as if it is sent from Victor to Peggy, and immediately outputs the value of r as if it is sent from Peggy to Victor. A single round is complete. On the other hand, if the coin flipping result is "tails", then Simon picks a random number r′, computes C′ = gr′ · y−1 mod p, and discloses C′ as if it is a message from Peggy to Victor. Then Simon outputs "request the value of (x + r) mod (p − 1)" as if it is a message from Victor to Peggy. Finally, Simon outputs the value of r′ as if it is the response from Peggy back to Victor. A single round is complete. By the previous arguments when proving the completeness and soundness, the interactive communication simulated by Simon is indistinguishable from the true correspondence between Peggy and Victor. The zero-knowledge property is thus guaranteed.

Hamiltonian cycle for a large graph

The following scheme is due to Manuel Blum.[14]

In this scenario, Peggy knows a Hamiltonian cycle for a large graph G. Victor knows G but not the cycle (e.g., Peggy has generated G and revealed it to him.) Finding a Hamiltonian cycle given a large graph is believed to be computationally infeasible, since its corresponding decision version is known to be NP-complete. Peggy will prove that she knows the cycle without simply revealing it (perhaps Victor is interested in buying it but wants verification first, or maybe Peggy is the only one who knows this information and is proving her identity to Victor).

To show that Peggy knows this Hamiltonian cycle, she and Victor play several rounds of a game:

- At the beginning of each round, Peggy creates H, a graph which is isomorphic to G (that is, H is just like G except that all the vertices have different names). Since it is trivial to translate a Hamiltonian cycle between isomorphic graphs with known isomorphism, if Peggy knows a Hamiltonian cycle for G then she also must know one for H.

- Peggy commits to H. She could do so by using a cryptographic commitment scheme. Alternatively, she could number the vertices of H. Next, for each edge of H, on a small piece of paper, she writes down the two vertices that the edge joins. Then she puts all these pieces of paper face down on a table. The purpose of this commitment is that Peggy is not able to change H while, at the same time, Victor has no information about H.

- Victor then randomly chooses one of two questions to ask Peggy. He can either ask her to show the isomorphism between H and G (see graph isomorphism problem), or he can ask her to show a Hamiltonian cycle in H.

- If Peggy is asked to show that the two graphs are isomorphic, then she first uncovers all of H (e.g. by turning over all pieces of papers that she put on the table) and then provides the vertex translations that map G to H. Victor can verify that they are indeed isomorphic.

- If Peggy is asked to prove that she knows a Hamiltonian cycle in H, then she translates her Hamiltonian cycle in G onto H and only uncovers the edges on the Hamiltonian cycle. That is, Peggy only turns over exactly |V(G)| of the pieces of paper that correspond to the edges of the Hamiltonian cycle, while leaving the rest still face-down. This is enough for Victor to check that H does indeed contain a Hamiltonian cycle.

It is important that the commitment to the graph be such that Victor can verify, in the second case, that the cycle is really made of edges from H. This can be done by, for example, committing to every edge (or lack thereof) separately.

Completeness

If Peggy does know a Hamiltonian cycle in G, then she can easily satisfy Victor's demand for either the graph isomorphism producing H from G (which she had committed to in the first step) or a Hamiltonian cycle in H (which she can construct by applying the isomorphism to the cycle in G).

Zero-knowledge

Peggy's answers do not reveal the original Hamiltonian cycle in G. In each round, Victor will learn only H's isomorphism to G or a Hamiltonian cycle in H. He would need both answers for a single H to discover the cycle in G, so the information remains unknown as long as Peggy can generate a distinct H every round. If Peggy does not know of a Hamiltonian cycle in G, but somehow knew in advance what Victor would ask to see each round, then she could cheat. For example, if Peggy knew ahead of time that Victor would ask to see the Hamiltonian cycle in H, then she could generate a Hamiltonian cycle for an unrelated graph. Similarly, if Peggy knew in advance that Victor would ask to see the isomorphism then she could simply generate an isomorphic graph H (in which she also does not know a Hamiltonian cycle). Victor could simulate the protocol by himself (without Peggy) because he knows what he will ask to see. Therefore, Victor gains no information about the Hamiltonian cycle in G from the information revealed in each round.

Soundness

If Peggy does not know the information, then she can guess which question Victor will ask and generate either a graph isomorphic to G or a Hamiltonian cycle for an unrelated graph, but since she does not know a Hamiltonian cycle for G, she cannot do both. With this guesswork, her chance of fooling Victor is 2−n, where n is the number of rounds. For all realistic purposes, it is infeasibly difficult to defeat a zero-knowledge proof with a reasonable number of rounds in this way.

Variants of zero-knowledge

Different variants of zero-knowledge can be defined by formalizing the intuitive concept of what is meant by the output of the simulator "looking like" the execution of the real proof protocol in the following ways:

- We speak of perfect zero-knowledge if the distributions produced by the simulator and the proof protocol are distributed exactly the same. This is for instance the case in the first example above.

- Statistical zero-knowledge[15] means that the distributions are not necessarily exactly the same, but they are statistically close, meaning that their statistical difference is a negligible function.

- We speak of computational zero-knowledge if no efficient algorithm can distinguish the two distributions.

Zero knowledge types

There are various types of zero-knowledge proofs:

- Proof of knowledge: the knowledge is hidden in the exponent like in the example shown above.

- Witness-indistinguishable proof: verifiers cannot know which witness is used for producing the proof.

Zero-knowledge proof schemes can be constructed from various cryptographic primitives, such as hash-based cryptography, pairing-based cryptography, multi-party computation, or lattice-based cryptography.

Applications

Authentication systems

In April 2015, the one-out-of-many proofs protocol (a Sigma protocol) was introduced.[16] In August 2021, Cloudflare, an American web infrastructure and security company, decided to use the one-out-of-many proofs mechanism for private web verification using vendor hardware.[17]

Ethical behavior

One of the uses of zero-knowledge proofs within cryptographic protocols is to enforce honest behavior while maintaining privacy. Roughly, the idea is to force a user to prove, using a zero-knowledge proof, that its behavior is correct according to the protocol.[18][19] Because of soundness, we know that the user must really act honestly in order to be able to provide a valid proof. Because of zero knowledge, we know that the user does not compromise the privacy of its secrets in the process of providing the proof.

Nuclear disarmament

In 2016, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory and Princeton University demonstrated a technique that may have applicability to future nuclear disarmament talks. It would allow inspectors to confirm whether or not an object is indeed a nuclear weapon without recording, sharing, or revealing the internal workings, which might be secret.[20]

Blockchains

Zero-knowledge proofs were applied in the Zerocoin and Zerocash protocols, which culminated in the birth of Zcoin[21] (later rebranded as Firo in 2020)[22] and Zcash cryptocurrencies in 2016. Zerocoin has a built-in mixing model that does not trust any peers or centralised mixing providers to ensure anonymity.[21] Users can transact in a base currency and can cycle the currency into and out of Zerocoins.[23] The Zerocash protocol uses a similar model (a variant known as a non-interactive zero-knowledge proof)[24] except that it can obscure the transaction amount, while Zerocoin cannot. Given significant restrictions of transaction data on the Zerocash network, Zerocash is less prone to privacy timing attacks when compared to Zerocoin. However, this additional layer of privacy can cause potentially undetected hyperinflation of Zerocash supply because fraudulent coins cannot be tracked.[21][25]

In 2018, Bulletproofs were introduced. Bulletproofs are an improvement from non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs where a trusted setup is not needed.[26] It was later implemented into the Mimblewimble protocol (which the Grin and Beam cryptocurrencies are based upon) and Monero cryptocurrency.[27] In 2019, Firo implemented the Sigma protocol, which is an improvement on the Zerocoin protocol without trusted setup.[28][16] In the same year, Firo introduced the Lelantus protocol, an improvement on the Sigma protocol, where the former hides the origin and amount of a transaction.[29]

A related line of work applies zero-knowledge proofs to database analytics via so-called zero-knowledge "coprocessors": off-chain systems that execute queries and return both the result and a proof that the computation was performed correctly on untampered data. Academic prototypes have shown how to produce ZK proofs for ad-hoc SQL queries while hiding inputs and guaranteeing correctness of the result (e.g., ZKSQL).[30] One implementation of this approach, termed "Proof of SQL", has been reported in industry media as enabling sub-second ZK proving for SQL query results and making the prover available as open source.[31][32] Earlier coverage also described the concept under development as a cryptographic protocol allowing decentralized applications to verify that SQL results have not been tampered with.[33][34]

Decentralized Identifiers

Zero-knowledge proofs by their nature can enhance privacy in identity-sharing systems, which are vulnerable to data breaches and identity theft. When integrated to a decentralized identifier system, ZKPs add an extra layer of encryption on DID documents.[35]

History

Zero-knowledge proofs were first conceived in 1985 by Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Charles Rackoff in their paper "The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof-Systems".[18] This paper introduced the IP hierarchy of interactive proof systems (see interactive proof system) and conceived the concept of knowledge complexity, a measurement of the amount of knowledge about the proof transferred from the prover to the verifier. They also gave the first zero-knowledge proof for a concrete problem, that of deciding quadratic nonresidues mod m. Together with a paper by László Babai and Shlomo Moran, this landmark paper invented interactive proof systems, for which all five authors won the first Gödel Prize in 1993.

In their own words, Goldwasser, Micali, and Rackoff say:

Of particular interest is the case where this additional knowledge is essentially 0 and we show that [it] is possible to interactively prove that a number is quadratic non residue mod m releasing 0 additional knowledge. This is surprising as no efficient algorithm for deciding quadratic residuosity mod m is known when m's factorization is not given. Moreover, all known NP proofs for this problem exhibit the prime factorization of m. This indicates that adding interaction to the proving process, may decrease the amount of knowledge that must be communicated in order to prove a theorem.

The quadratic nonresidue problem has both an NP and a co-NP algorithm, and so lies in the intersection of NP and co-NP. This was also true of several other problems for which zero-knowledge proofs were subsequently discovered, such as an unpublished proof system by Oded Goldreich verifying that a two-prime modulus is not a Blum integer.[36]

Oded Goldreich, Silvio Micali, and Avi Wigderson took this one step further, showing that, assuming the existence of unbreakable encryption, one can create a zero-knowledge proof system for the NP-complete graph coloring problem with three colors. Since every problem in NP can be efficiently reduced to this problem, this means that, under this assumption, all problems in NP have zero-knowledge proofs.[37] The reason for the assumption is that, as in the above example, their protocols require encryption. A commonly cited sufficient condition for the existence of unbreakable encryption is the existence of one-way functions, but it is conceivable that some physical means might also achieve it.

On top of this, they also showed that the graph nonisomorphism problem, the complement of the graph isomorphism problem, has a zero-knowledge proof. This problem is in co-NP, but is not currently known to be in either NP or any practical class. More generally, Russell Impagliazzo and Moti Yung as well as Ben-Or et al. would go on to show that, also assuming one-way functions or unbreakable encryption, there are zero-knowledge proofs for all problems in IP = PSPACE, or in other words, anything that can be proved by an interactive proof system can be proved with zero knowledge.[38][39]

Not liking to make unnecessary assumptions, many theorists sought a way to eliminate the necessity of one way functions. One way this was done was with multi-prover interactive proof systems (see interactive proof system), which have multiple independent provers instead of only one, allowing the verifier to "cross-examine" the provers in isolation to avoid being misled. It can be shown that, without any intractability assumptions, all languages in NP have zero-knowledge proofs in such a system.[40]

It turns out that, in an Internet-like setting, where multiple protocols may be executed concurrently, building zero-knowledge proofs is more challenging. The line of research investigating concurrent zero-knowledge proofs was initiated by the work of Dwork, Naor, and Sahai.[41] One particular development along these lines has been the development of witness-indistinguishable proof protocols. The property of witness-indistinguishability is related to that of zero-knowledge, yet witness-indistinguishable protocols do not suffer from the same problems of concurrent execution.[42]

Another variant of zero-knowledge proofs are non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs. Blum, Feldman, and Micali showed that a common random string shared between the prover and the verifier is enough to achieve computational zero-knowledge without requiring interaction.[5][6]

Zero-Knowledge Proof protocols

The most popular interactive or non-interactive zero-knowledge proof (e.g., zk-SNARK) protocols can be broadly categorized in the following four categories: Succinct Non-Interactive ARguments of Knowledge (SNARK), Scalable Transparent ARgument of Knowledge (STARK), Verifiable Polynomial Delegation (VPD), and Succinct Non-interactive ARGuments (SNARG). A list of zero-knowledge proof protocols and libraries is provided below along with comparisons based on transparency, universality, plausible post-quantum security, and programming paradigm.[43] A transparent protocol is one that does not require any trusted setup and uses public randomness. A universal protocol is one that does not require a separate trusted setup for each circuit. Finally, a plausibly post-quantum protocol is one that is not susceptible to known attacks involving quantum algorithms.

| ZKP System | Publication year | Protocol | Transparent | Universal | Plausibly Post-Quantum Secure | Programming Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinocchio[44] | 2013 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| Geppetto[45] | 2015 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| TinyRAM[46] | 2013 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| Buffet[47] | 2015 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| ZoKrates[48] | 2018 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| xJsnark[49] | 2018 | zk-SNARK | No | No | No | Procedural |

| vRAM[50] | 2018 | zk-SNARG | No | Yes | No | Assembly |

| vnTinyRAM[51] | 2014 | zk-SNARK | No | Yes | No | Procedural |

| MIRAGE[52] | 2020 | zk-SNARK | No | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Sonic[53] | 2019 | zk-SNARK | No | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Marlin[54] | 2020 | zk-SNARK | No | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| PLONK[55] | 2019 | zk-SNARK | No | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| SuperSonic[56] | 2020 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Bulletproofs[26] | 2018 | Bulletproofs | Yes | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Hyrax[57] | 2018 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Halo[58] | 2019 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | No | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Virgo[59] | 2020 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Ligero[60] | 2017 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Arithmetic Circuits |

| Aurora[61] | 2019 | zk-SNARK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Arithmetic Circuits |

| zk-STARK[62] | 2019 | zk-STARK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Assembly |

| Zilch[43] | 2021 | zk-STARK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Object-Oriented |

Security vulnerabilities of zero-knowledge systems

While zero-knowledge proofs offer a secure way to verify information, the arithmetic circuits that implement them must be carefully designed. If these circuits lack sufficient constraints, they may introduce subtle yet critical security vulnerabilities.

One of the most common classes of vulnerabilities in these systems is under-constrained logic, where insufficient constraints allow a malicious prover to produce a proof for an incorrect statement that still passes verification. A 2024 systematization of known attacks found that approximately 96% of documented circuit-layer bugs in SNARK-based systems were due to under-constrained circuits.[63]

These vulnerabilities often arise during the translation of high-level logic into low-level constraint systems, particularly when using domain-specific languages such as Circom or Gnark. Recent research has demonstrated that formally proving determinism – ensuring that a circuit's outputs are uniquely determined by its inputs – can eliminate entire classes of these vulnerabilities.[64]

See also

- Social:Arrow information paradox

- Cryptographic protocol – Aspect of cryptography

- Probabilistically checkable proof – Proof checkable by a randomized algorithm

- Proof of knowledge – Class of interactive proof

- Witness-indistinguishable proof – Variant of a zero-knowledge proof for languages in NP

- Zero-knowledge password proof

- Non-interactive zero-knowledge proof

External links

- Computer scientist Amit Sahai explains the Zero-knowledge proof in 5 Levels of Difficulty on YouTube

References

- ↑ Aad, Imad (2023), Mulder, Valentin; Mermoud, Alain; Lenders, Vincent et al., eds., "Zero-Knowledge Proof" (in en), Trends in Data Protection and Encryption Technologies (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland): pp. 25–30, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-33386-6_6, ISBN 978-3-031-33386-6

- ↑ Goldreich, Oded (2001). Foundations of Cryptography Volume I. Cambridge University Press. p. 184. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511546891. ISBN 978-0-511-54689-1. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/foundations-of-cryptography/B61B6AD235D2034D511A5FF740415166.

- ↑ Goldreich, Oded (2001). Foundations of Cryptography Volume I. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511546891. ISBN 978-0-511-54689-1. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/foundations-of-cryptography/B61B6AD235D2034D511A5FF740415166.

- ↑ Goldreich, Oded (2001). Foundations of Cryptography Volume I. Cambridge University Press. p. 299. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511546891. ISBN 978-0-511-54689-1. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/foundations-of-cryptography/B61B6AD235D2034D511A5FF740415166.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Blum, Manuel; Feldman, Paul; Micali, Silvio (1988). "Non-interactive zero-knowledge and its applications". Proceedings of the twentieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing - STOC '88. pp. 103–112. doi:10.1145/62212.62222. ISBN 978-0-89791-264-8. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA222698.pdf. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wu, Huixin; Wang, Feng (2014). "A Survey of Noninteractive Zero Knowledge Proof System and Its Applications". The Scientific World Journal 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/560484. PMID 24883407.

- ↑ "Playing Card Cryptography". Four Years Remaining. https://fouryears.eu/2015/03/09/playing-card-cryptography/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Murtagh, Jack (July 1, 2023). "Where's Wally? How to Mathematically Prove You Found Him without Revealing Where He Is". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wheres-waldo-how-to-prove-you-found-him-without-revealing-where-he-is/.

- ↑ Quisquater, Jean-Jacques; Guillou, Louis C.; Berson, Thomas A. (1990). "How to Explain Zero-Knowledge Protocols to Your Children". Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO' 89 Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 435. pp. 628–631. doi:10.1007/0-387-34805-0_60. ISBN 978-0-387-97317-3. http://www.cs.wisc.edu/~mkowalcz/628.pdf.

- ↑ Chalkias, Konstantinos. "Demonstrate how Zero-Knowledge Proofs work without using maths" (in en). CordaCon 2017. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/demonstrate-how-zero-knowledge-proofs-work-without-using-chalkias.

- ↑ Feige, Uriel; Fiat, Amos; Shamir, Adi (1988-06-01). "Zero-knowledge proofs of identity" (in en). Journal of Cryptology 1 (2): 77–94. doi:10.1007/BF02351717. ISSN 1432-1378.

- ↑ Ishai, Yuval; Kushilevitz, Eyal; Ostrovsky, Rafail; Sahai, Amit (2007). "Zero-Knowledge from Secure Multiparty Computation". doi:10.1145/1250790.1250794. ISBN 978-1-59593-631-8. https://web.cs.ucla.edu/~rafail/PUBLIC/77.pdf. Retrieved 2025-09-25.

- ↑ Chaum, David; Evertse, Jan-Hendrik; van de Graaf, Jeroen (1988). "An Improved Protocol for Demonstrating Possession of Discrete Logarithms and Some Generalizations". Advances in Cryptology — EUROCRYPT '87. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 304. pp. 127–141. doi:10.1007/3-540-39118-5_13. ISBN 978-3-540-19102-5.

- ↑ Blum, Manuel (1986). "How to Prove a Theorem So No One Else Can Claim It". ICM Proceedings: 1444–1451. http://euler.nmt.edu/~brian/students/pope.pdf.

- ↑ Sahai, Amit; Vadhan, Salil (1 March 2003). "A complete problem for statistical zero knowledge". Journal of the ACM 50 (2): 196–249. doi:10.1145/636865.636868. http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/4728406/Vadhan_StatZeroKnow.pdf?sequence=2.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Groth, J; Kohlweiss, M (14 April 2015). "One-Out-of-Many Proofs: Or How to Leak a Secret and Spend a Coin". Advances in Cryptology - EUROCRYPT 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 9057. Berlin, Heidelberg: EUROCRYPT 2015. pp. 253–280. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46803-6_9. ISBN 978-3-662-46802-9. https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/f6ec5d8f-cfda-4f56-9bd0-d9222b8d9a43.

- ↑ "Introducing Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Private Web attestation with Cross/Multi-Vendor Hardware" (in en). 2021-08-12. https://blog.cloudflare.com/introducing-zero-knowledge-proofs-for-private-web-attestation-with-cross-multi-vendor-hardware/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goldwasser, S.; Micali, S.; Rackoff, C. (1989), "The knowledge complexity of interactive proof systems", SIAM Journal on Computing 18 (1): 186–208, doi:10.1137/0218012, ISSN 1095-7111, http://people.csail.mit.edu/silvio/Selected%20Scientific%20Papers/Proof%20Systems/The_Knowledge_Complexity_Of_Interactive_Proof_Systems.pdf

- ↑ Abascal, Jackson; Faghihi Sereshgi, Mohammad Hossein; Hazay, Carmit; Ishai, Yuval; Venkitasubramaniam, Muthuramakrishnan (2020-10-30). "Is the Classical GMW Paradigm Practical? The Case of Non-Interactive Actively Secure 2PC". Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. CCS '20. Virtual Event, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1591–1605. doi:10.1145/3372297.3423366. ISBN 978-1-4503-7089-9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372297.3423366.

- ↑ "PPPL and Princeton demonstrate novel technique that may have applicability to future nuclear disarmament talks - Princeton Plasma Physics Lab". https://www.pppl.gov/news/2022/pppl-and-princeton-demonstrate-novel-technique-may-have-applicability-future-nuclear.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hellwig, Daniel; Karlic, Goran; Huchzermeier, Arnd (3 May 2020). "Privacy and Anonymity". Build Your Own Blockchain. Management for Professionals. SpringerLink. p. 112. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40142-9_5. ISBN 978-3-030-40142-9. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-40142-9_5. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Hurst, Samantha (28 October 2020). "Zcoin Announces Rebranding to New Name & Ticker "Firo"". Crowdfund Insider. https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2020/10/168504-zcoin-announces-rebranding-to-new-name-ticker-firo/.

- ↑ Bonneau, J; Miller, A; Clark, J; Narayanan, A (2015). "SoK: Research Perspectives and Challenges for Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies". 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. San Jose, California. pp. 104–121. doi:10.1109/SP.2015.14. ISBN 978-1-4673-6949-7.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Garman, Christina; Green, Matthew; Miers, Ian; Tromer, Eran; Virza, Madars (18 May 2014). "Zerocash: Decentralized Anonymous Payments from Bitcoin". IEEE. http://zerocash-project.org/media/pdf/zerocash-extended-20140518.pdf.

- ↑ Orcutt, Mike. "A mind-bending cryptographic trick promises to take blockchains mainstream" (in en). MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609448/a-mind-bending-cryptographic-trick-promises-to-take-blockchains-mainstream.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Bünz, B; Bootle, D; Boneh, A (2018). "Bulletproofs: Short Proofs for Confidential Transactions and More". 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). San Francisco, California. pp. 315–334. doi:10.1109/SP.2018.00020. ISBN 978-1-5386-4353-2.

- ↑ Odendaal, Hansie; Sharrock, Cayle; Heerden, SW. "Bulletproofs and Mimblewimble". Tari Labs University. https://tlu.tarilabs.com/cryptography/bulletproofs-and-mimblewimble/MainReport.html#current-and-past-efforts.

- ↑ Andrew, Munro (30 July 2019). "Zcoin cryptocurrency introduces zero knowledge proofs with no trusted set-up". Finder Australia. https://www.finder.com.au/zcoin-cryptocurrency-introduces-zero-knowledge-proofs-with-no-trusted-setup.

- ↑ Aram, Jivanyan (7 April 2019). "Lelantus: Towards Confidentiality and Anonymity of Blockchain Transactions from Standard Assumptions". Cryptology ePrint Archive (Report 373). https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/373. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ↑ Li, X.; others (2023). "ZKSQL: Verifiable and Efficient Query Evaluation with Zero-Knowledge Proofs". Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 16 (8): 1804–1817. doi:10.14778/3594512.3594513. https://www.vldb.org/pvldb/vol16/p1804-li.pdf.

- ↑ "Protocol Village: Space and Time Releases 'Proof of SQL v1' With Sub-Second ZK Prover". CoinDesk. 12 June 2024. https://www.coindesk.com/tech/2024/06/11/protocol-village.

- ↑ "New open-source ZK-proof slashes SQL query times". Cointelegraph. 12 June 2024. https://cointelegraph.com/news/open-source-zk-proof-slashes-sql-query-times-sub-seconds.

- ↑ Betz, Brandy (28 July 2022). "Decentralized Data Platform Space and Time Raises $10M". CoinDesk. https://www.coindesk.com/business/2022/07/28/decentralized-data-platform-space-and-time-raises-10m.

- ↑ "Microsoft's M12 leads Space and Time's $20 million raise to bring SQL to Web3". The Block. 27 September 2022. https://www.theblock.co/post/172780/microsofts-m12-leads-space-and-times-20-million-raise-to-bring-sql-to-web3.

- ↑ Zhou, Lu; Diro, Abebe; Saini, Akanksha; Kaisar, Shahriar; Hiep, Pham Cong (2024-02-01). "Leveraging zero knowledge proofs for blockchain-based identity sharing: A survey of advancements, challenges and opportunities". Journal of Information Security and Applications 80. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103678. ISSN 2214-2126.

- ↑ Goldreich, Oded (1985). "A zero-knowledge proof that a two-prime moduli is not a Blum integer". Unpublished Manuscript.

- ↑ Goldreich, Oded; Micali, Silvio; Wigderson, Avi (1991). "Proofs that yield nothing but their validity". Journal of the ACM 38 (3): 690–728. doi:10.1145/116825.116852.

- ↑ Russell Impagliazzo, Moti Yung: Direct Minimum-Knowledge Computations. CRYPTO 1987: 40–51

- ↑ Ben-Or, Michael; Goldreich, Oded; Goldwasser, Shafi; Hastad, Johan; Kilian, Joe; Micali, Silvio; Rogaway, Phillip (1990). "Everything provable is provable in zero-knowledge". in Goldwasser, S.. Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO '88. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 403. Springer-Verlag. pp. 37–56.

- ↑ Ben-Or, Michael; Goldwasser, Shafi; Kilian, Joe; Widgerson, Avi (1988). "Multi-prover interactive proofs: How to remove intractability". Proceedings of the twentieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing - STOC '88. pp. 113–131. doi:10.1145/62212.62223. ISBN 0-89791-264-0. https://doi.org/10.1145/62212.62223.

- ↑ Dwork, Cynthia; Naor, Moni; Sahai, Amit (2004). "Concurrent Zero Knowledge". Journal of the ACM 51 (6): 851–898. doi:10.1145/1039488.1039489.

- ↑ Feige, Uriel; Shamir, Adi (1990). "Witness indistinguishable and witness hiding protocols". Proceedings of the twenty-second annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing - STOC '90. pp. 416–426. doi:10.1145/100216.100272. ISBN 978-0-89791-361-4.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Mouris, Dimitris; Tsoutsos, Nektarios Georgios (2021). "Zilch: A Framework for Deploying Transparent Zero-Knowledge Proofs". IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 16: 3269–3284. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2021.3074869. ISSN 1556-6021. Bibcode: 2021ITIF...16.3269M.

- ↑ Parno, B.; Howell, J.; Gentry, C.; Raykova, M. (May 2013). "Pinocchio: Nearly Practical Verifiable Computation". 2013 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. pp. 238–252. doi:10.1109/SP.2013.47. ISBN 978-0-7695-4977-4.

- ↑ Costello, Craig; Fournet, Cedric; Howell, Jon; Kohlweiss, Markulf; Kreuter, Benjamin; Naehrig, Michael; Parno, Bryan; Zahur, Samee (May 2015). "Geppetto: Versatile Verifiable Computation". 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. pp. 253–270. doi:10.1109/SP.2015.23. ISBN 978-1-4673-6949-7. https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/37920e55-65aa-4a42-b678-ef5902a5dd45.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Genkin, Daniel; Tromer, Eran; Virza, Madars (2013). "SNARKs for C: Verifying Program Executions Succinctly and in Zero Knowledge". Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 8043. pp. 90–108. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40084-1_6. ISBN 978-3-642-40083-4.

- ↑ Wahby, Riad S.; Setty, Srinath; Ren, Zuocheng; Blumberg, Andrew J.; Walfish, Michael (2015). "Efficient RAM and Control Flow in Verifiable Outsourced Computation". Proceedings 2015 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. doi:10.14722/ndss.2015.23097. ISBN 978-1-891562-38-9.

- ↑ Eberhardt, Jacob; Tai, Stefan (July 2018). "ZoKrates - Scalable Privacy-Preserving Off-Chain Computations". 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (IThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData). pp. 1084–1091. doi:10.1109/Cybermatics_2018.2018.00199. ISBN 978-1-5386-7975-3.

- ↑ Kosba, Ahmed; Papamanthou, Charalampos; Shi, Elaine (May 2018). "XJsnark: A Framework for Efficient Verifiable Computation". 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). pp. 944–961. doi:10.1109/SP.2018.00018. ISBN 978-1-5386-4353-2.

- ↑ Zhang, Yupeng; Genkin, Daniel; Katz, Jonathan; Papadopoulos, Dimitrios; Papamanthou, Charalampos (May 2018). "VRAM: Faster Verifiable RAM with Program-Independent Preprocessing". 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). pp. 908–925. doi:10.1109/SP.2018.00013. ISBN 978-1-5386-4353-2.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Tromer, Eran; Virza, Madars (20 August 2014). "Succinct non-interactive zero knowledge for a von Neumann architecture". Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Conference on Security Symposium (USENIX Association): 781–796. ISBN 978-1-931971-15-7. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity14/technical-sessions/presentation/ben-sasson.

- ↑ Kosba, Ahmed; Papadopoulos, Dimitrios; Papamanthou, Charalampos; Song, Dawn (2020). "MIRAGE: Succinct Arguments for Randomized Algorithms with Applications to Universal zk-SNARKs". Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/278.

- ↑ Maller, Mary; Bowe, Sean; Kohlweiss, Markulf; Meiklejohn, Sarah (6 November 2019). "Sonic: Zero-Knowledge SNARKs from Linear-Size Universal and Updatable Structured Reference Strings". Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 2111–2128. doi:10.1145/3319535.3339817. ISBN 978-1-4503-6747-9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319535.3339817.

- ↑ Chiesa, Alessandro; Hu, Yuncong; Maller, Mary; Mishra, Pratyush; Vesely, Noah; Ward, Nicholas (2020). "Marlin: Preprocessing zkSNARKs with Universal and Updatable SRS" (in en). Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 12105. Springer International Publishing. pp. 738–768. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45721-1_26. ISBN 978-3-030-45720-4. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-45721-1_26.

- ↑ Gabizon, Ariel; Williamson, Zachary J.; Ciobotaru, Oana (2019). "PLONK: Permutations over Lagrange-bases for Oecumenical Noninteractive arguments of Knowledge". Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/953.

- ↑ Bünz, Benedikt; Fisch, Ben; Szepieniec, Alan (2020). "Transparent SNARKs from DARK Compilers" (in en). Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 12105. Springer International Publishing. pp. 677–706. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45721-1_24. ISBN 978-3-030-45720-4. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-45721-1_24.

- ↑ Wahby, Riad S.; Tzialla, Ioanna; Shelat, Abhi; Thaler, Justin; Walfish, Michael (May 2018). "Doubly-Efficient zkSNARKs Without Trusted Setup". 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). pp. 926–943. doi:10.1109/SP.2018.00060. ISBN 978-1-5386-4353-2.

- ↑ Bowe, Sean; Grigg, Jack; Hopwood, Daira (2019). "Recursive Proof Composition without a Trusted Setup". Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/1021.

- ↑ Zhang, Jiaheng; Xie, Tiancheng; Zhang, Yupeng; Song, Dawn (May 2020). "Transparent Polynomial Delegation and Its Applications to Zero Knowledge Proof". 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). pp. 859–876. doi:10.1109/SP40000.2020.00052. ISBN 978-1-7281-3497-0.

- ↑ Ames, Scott; Hazay, Carmit; Ishai, Yuval; Venkitasubramaniam, Muthuramakrishnan (30 October 2017). "Ligero". Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 2087–2104. doi:10.1145/3133956.3134104. ISBN 978-1-4503-4946-8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3133956.3134104.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Riabzev, Michael; Spooner, Nicholas; Virza, Madars; Ward, Nicholas P. (2019). "Aurora: Transparent Succinct Arguments for R1CS" (in en). Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 11476. Springer International Publishing. pp. 103–128. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17653-2_4. ISBN 978-3-030-17652-5. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-030-17653-2_4.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Bentov, Iddo; Horesh, Yinon; Riabzev, Michael (2019). "Scalable Zero Knowledge with No Trusted Setup" (in en). Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 11694. Springer International Publishing. pp. 701–732. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-26954-8_23. ISBN 978-3-030-26953-1. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-26954-8_23.

- ↑ Chaliasos, Stefanos; Ernstberger, Jens; Theodore, David; Wong, David; Jahanara, Mohammad; Livshits, Benjamin (2024). "SoK: What Don't We Know? Understanding Security Vulnerabilities in SNARKs". SEC '24: Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Conference on Security Symposium. pp. 3855–3872. ISBN 978-1-939133-44-1. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3698900.3699116.

- ↑ Pailoor, Shankara; Chen, Yanju; Wang, Franklyn; Rodríguez, Clara; Van Geffen, Jacob; Morton, Jason; Chu, Michael; Gu, Brian et al. (2023). "Automated Detection of Under-Constrained Circuits in Zero-Knowledge Proofs". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 7: 1510–1532. doi:10.1145/3591282.

|