Religion:Basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its name to the architectural form of the basilica.

Originally, a basilica was an ancient Roman public building, where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. Basilicas are typically rectangular buildings with a central nave flanked by two or more longitudinal aisles, with the roof at two levels, being higher in the centre over the nave to admit a clerestory and lower over the side-aisles. An apse at one end, or less frequently at both ends or on the side, usually contained the raised tribunal occupied by the Roman magistrates. The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the forum and often opposite a temple in imperial-era forums.[1] Basilicas were also built in private residences and imperial palaces and were known as "palace basilicas".

In late antiquity, church buildings were typically constructed either as martyria, or with a basilica's architectural plan. A number of monumental Christian basilicas were constructed during the latter reign of Constantine the Great. In the post Nicene period, basilicas became a standard model for Christian spaces for congregational worship throughout the Mediterranean and Europe. From the early 4th century, Christian basilicas, along with their associated catacombs, were used for burial of the dead.

By extension, the name was later applied to Christian churches that adopted the same basic plan. It continues to be used in an architectural sense to describe rectangular buildings with a central nave and aisles, and usually a raised platform at the end opposite the door. In Europe and the Americas, the basilica remained the most common architectural style for churches of all Christian denominations, though this building plan has become less dominant in buildings constructed since the late 20th century.

The Catholic Church has come to use the term to refer to its especially historic churches, without reference to the architectural form.

Origins

The Latin word basilica derives from Ancient Greek:. The first known basilica—the Basilica Porcia in the Roman Forum—was constructed in 184 BC by Marcus Porcius Cato (the Elder).[2] After the construction of Cato the Elder's basilica, the term came to be applied to any large covered hall, whether it was used for domestic purposes, was a commercial space, a military structure, or religious building.[2]

The plays of Plautus suggest that basilica buildings may have existed prior to Cato's building. The plays were composed between 210 and 184 BC and refer to a building that might be identified with the Atrium Regium.[3] Another early example is the basilica at Pompeii (late 2nd century BC). Inspiration may have come from prototypes like Athens's Stoa Basileios or the hypostyle hall on Delos, but the architectural form is most derived from the audience halls in the royal palaces of the Diadochi kingdoms of the Hellenistic period. These rooms were typically a high nave flanked by colonnades.[3]

These basilicas were rectangular, typically with central nave and aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.[4][5] The Roman basilica was a large public building where business or legal matters could be transacted. As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used in the same way as the covered market houses of late medieval northern Europe, where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades, however.[clarify][citation needed] Although their form was variable, basilicas often contained interior colonnades that divided the space, giving aisles or arcaded spaces on one or both sides, with an apse at one end (or less often at each end), where the magistrates sat, often on a slightly raised dais. The central aisle – the nave – tended to be wider and taller than the flanking aisles, so that light could penetrate through the clerestory windows.[citation needed]

In the late Republican era, basilicas were increasingly monumental; Julius Caesar replaced the Basilica Sempronia with his own Basilica Julia, dedicated in 46 BC, while the Basilica Aemilia was rebuilt around 54 BC in so spectacular a fashion that Pliny the Elder wrote that it was among the most beautiful buildings in the world (it was simultaneously renamed the Basilica Paulli). Thereafter until the 4th century AD, monumental basilicas were routinely constructed at Rome by both private citizens and the emperors. These basilicas were reception halls and grand spaces in which élite persons could impress guests and visitors, and could be attached to a large country villa or an urban domus. They were simpler and smaller than were civic basilicas, and can be identified by inscriptions or their position in the archaeological context. Domitian constructed a basilica on the Palatine Hill for his imperial residential complex around 92 AD, and a palatine basilica was typical in imperial palaces throughout the imperial period.[3]

Roman Republic

Long, rectangular basilicas with internal peristyle became a quintessential element of Roman urbanism, often forming the architectural background to the city forum and used for diverse purposes.[6] Beginning with Cato in the early second century BC, politicians of the Roman Republic competed with one another by building basilicas bearing their names in the Forum Romanum, the centre of ancient Rome. Outside the city, basilicas symbolised the influence of Rome and became a ubiquitous fixture of Roman coloniae of the late Republic from c. 100 BC. The earliest surviving basilica is the basilica of Pompeii, built 120 BC.[6] Basilicas were the administrative and commercial centres of major Roman settlements: the "quintessential architectural expression of Roman administration".[7] Adjoining it there were normally various offices and rooms housing the curia and a shrine for the tutela.[8] Like Roman public baths, basilicas were commonly used as venues for the display of honorific statues and other sculptures, complementing the outdoor public spaces and thoroughfares.[9]

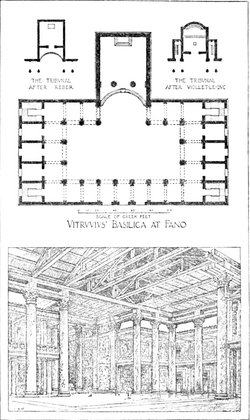

Beside the Basilica Porcia on the Forum Romanum, the Basilica Aemilia was built in 179 BC, and the Basilica Sempronia in 169 BC.[3] In the Republic two types of basilica were built across Italy in the mid-2nd to early 1st centuries BC: either they were nearly square as at Fanum Fortunae, designed by Vitruvius, and Cosa, with a 3:4 width-length ratio; or else they were more rectangular, as Pompeii's basilica, whose ratio is 3:7.[10][3]

The basilica at Ephesus is typical of the basilicas in the Roman East, which usually have a very elongated footprint and a ratio between 1:5 and 1:9, with open porticoes facing the agora (the Hellenic forum); this design was influenced by the existing tradition of long stoae in Hellenistic Asia.[3] Provinces in the west lacked this tradition, and the basilicas the Romans commissioned there were more typically Italian, with the central nave divided from the side-aisles by an internal colonnade in regular proportions.[3]

Early Empire

Beginning with the Forum of Caesar (Latin: forum Iulium) at the end of the Roman Republic, the centre of Rome was embellished with a series of imperial fora typified by a large open space surrounded by a peristyle, honorific statues of the imperial family (gens), and a basilica, often accompanied by other facilities like a temple, market halls and public libraries.[6] In the imperial period, statues of the emperors with inscribed dedications were often installed near the basilicas' tribunals, as Vitruvius recommended. Examples of such dedicatory inscriptions are known from basilicas at Lucus Feroniae and Veleia in Italy and at Cuicul in Africa Proconsolaris, and inscriptions of all kinds were visible in and around basilicas.[11]

At Ephesus the basilica-stoa had two storeys and three aisles and extended the length of the civic agora's north side, complete with colossal statues of the emperor Augustus and his imperial family.[7]

The remains of a large subterranean Neopythagorean basilica dating from the 1st century AD were found near the Porta Maggiore in Rome in 1917, and is known as the Porta Maggiore Basilica.[citation needed][12]

After its destruction in 60 AD, Londinium (London) was endowed with its first forum and basilica under the Flavian dynasty.[13] The basilica delimited the northern edge of the forum with typical nave, aisles, and a tribunal, but with an atypical semi-basement at the western side.[13] Unlike in Gaul, basilica-forum complexes in Roman Britain did not usually include a temple; instead a shrine was usually inside the basilica itself.[13] At Londinium however, there was probably no temple at all attached to the original basilica, but instead a contemporary temple was constructed nearby.[13] Later, in 79 AD, an inscription commemorated the completion of the 385 by 120 foot (117 m × 37 m) basilica at Verulamium (St Albans) under the governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola; by contrast the first basilica at Londinium was only 148 by 75 feet (45 m × 23 m).[13] The smallest known basilica in Britain was built by the Silures at Caerwent and measured 180 by 100 feet (55 m × 30 m).[13]

When Londinium became a colonia, the whole city was re-planned and a new great forum-basilica complex erected, larger than any in Britain.[14] Londinium's basilica, more than 500 feet (150 m) long, was the largest north of the Alps and a similar length to the modern St Paul's Cathedral.[14] Only the later basilica-forum complex at Treverorum was larger, while at Rome only the 525 foot (160 m) Basilica Ulpia exceeded London's in size.[14] It probably had arcaded, rather than trabeate, aisles, and a double row of square offices on the northern side, serving as the administrative centre of the colonia, and its size and splendour probably indicate an imperial decision to change the administrative capital of Britannia to Londinium from Camulodunum (Colchester), as all provincial capitals were designated coloniae.[14] In 300 Londinium's basilica was destroyed as a result of the rebellion led by the Augustus of the break-away Britannic Empire, Carausius.[15] Remains of the great basilica and its arches were discovered during the construction of Leadenhall Market in the 1880s.[14]

At Corinth in the 1st century AD, a new basilica was constructed in on the east side of the forum.[7] It was possibly inside the basilica that Paul the Apostle, according to the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 18:12–17) was investigated and found innocent by the Suffect Consul Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus, the brother of Seneca the Younger, after charges were brought against him by members of the local Jewish diaspora.[7] Modern tradition instead associates the incident with an open-air inscribed bema in the forum itself.[7]

The emperor Trajan constructed his own imperial forum in Rome accompanied by his Basilica Ulpia dedicated in 112.[16][3] Trajan's Forum (Latin: forum Traiani) was separated from the Temple of Trajan, the Ulpian Library, and his famous Column depicting the Dacian Wars by the Basilica.[16][3] It was an especially grand example whose particular symmetrical arrangement with an apse at both ends was repeated in the provinces as a characteristic form.[3] To improve the quality of the Roman concrete used in the Basilica Ulpia, volcanic scoria from the Bay of Naples and Mount Vesuvius were imported which, though heavier, was stronger than the pumice available closer to Rome.[17] The Bailica Ulpia is probably an early example of tie bars to restrain the lateral thrust of the barrel vault resting on a colonnade; both tie-bars and scoria were used in contemporary work at the Baths of Trajan and later the Hadrianic domed vault of the Pantheon.[17]

In early 123, the augusta and widow of the emperor Trajan, Pompeia Plotina died. Hadrian, successor to Trajan, deified her and had a basilica constructed in her honour in southern Gaul.[18]

The Basilica Hilariana (built c. 145–155) was designed for the use of the cult of Cybele.[3]

The largest basilica built outside Rome was that built under the Antonine dynasty on the Byrsa hill in Carthage.[19] The basilica was built together with a forum of enormous size and was contemporary with a great complex of public baths and a new aqueduct system running for 82 miles (132 km), then the longest in the Roman Empire.[19]

The basilica at Leptis Magna, built by the Septimius Severus a century later in about 216 is a notable 3rd century AD example of the traditional type, most notable among the works influenced by the Basilica Ulpia.[2][3] The basilica at Leptis was built mainly of limestone ashlar, but the apses at either end were only limestone in the outer sections and built largely of rubble masonry faced with brick, with a number of decorative panels in opus reticulatum.[20] The basilica stood in a new forum and was accompanied by a programme of Severan works at Leptis including thermae, a new harbour, and a public fountain.[6] At Volubilis, principal city of Mauretania Tingitana, a basilica modelled on Leptis Magna's was completed during the short reign of Macrinus.[21]

Basilicas in the Roman Forum

- Basilica Porcia: first basilica built in Rome (184 BC), erected on the personal initiative and financing of the censor Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder) as an official building for the tribunes of the plebs

- Basilica Aemilia, built by the censor Aemilius Lepidus in 179 BC

- Basilica Sempronia, built by the censor Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 169 BC

- Basilica Opimia, erected probably by the consul Lucius Opimius in 121 BC, at the same time that he restored the temple of Concord (Platner, Ashby 1929)

- Basilica Julia, initially dedicated in 46 BC by Julius Caesar and completed by Augustus 27 BC to AD 14

- Basilica Argentaria, erected under Trajan, emperor from AD 98 to 117

- Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (built between AD 308 and 312)

Late antiquity

The aisled-hall plan of the basilica was adopted by a number of religious cults in late antiquity.[2] At Sardis, a monumental basilica housed the city's synagogue, serving the local Jewish diaspora.[22] New religions like Christianity required space for congregational worship, and the basilica was adapted by the early Church for worship.[8] Because they were able to hold large number of people, basilicas were adopted for Christian liturgical use after Constantine the Great. The early churches of Rome were basilicas with an apsidal tribunal and used the same construction techniques of columns and timber roofing.[2]

At the start of the 4th century at Rome there was a change in burial and funerary practice, moving away from earlier preferences for inhumation in cemeteries – popular from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD – to the newer practice of burial in catacombs and inhumation inside Christian basilicas themselves.[23] Conversely, new basilicas often were erected on the site of existing early Christian cemeteries and martyria, related to the belief in Bodily Resurrection, and the cult of the sacred dead became monumentalised in basilica form.[24] Traditional civic basilicas and bouleuteria declined in use with the weakening of the curial class (Latin: curiales) in the 4th and 5th centuries, while their structures were well suited to the requirements of congregational liturgies.[24] The conversion of these types of buildings into Christian basilicas was also of symbolic significance, asserting the dominance of Christianity and supplanting the old political function of public space and the city-centre with an emphatic Christian social statement.[24] Traditional monumental civic amenities like gymnasia, palaestrae, and thermae were also falling into disuse, and became favoured sites for the construction of new churches, including basilicas.[24]

Under Constantine, the basilica became the most prestigious style of church building, was "normative" for church buildings by the end of the 4th century, and were ubiquitous in western Asia, North Africa, and most of Europe by the close of the 7th century.[25] Christians also continued to hold services in synagogues, houses, and gardens, and continued practising baptism in rivers, ponds, and Roman bathhouses.[25][26]

The development of Christian basilicas began even before Constantine's reign: a 3rd-century mud-brick house at Aqaba had become a Christian church and was rebuilt as a basilica.[25] Within was a rectangular assembly hall with frescoes and at the east end an ambo, a cathedra, and an altar.[25] Also within the church were a catecumenon (for catechumens), a baptistery, a diaconicon, and a prothesis: all features typical of later 4th century basilica churches.[25] A Christian structure which included the prototype of the triumphal arch at the east end of later Constantinian basilicas.[25] Known as the Megiddo church, it was built at Kefar 'Othnay in Palestine, possibly c. 230, for or by the Roman army stationed at Legio (later Lajjun).[25] Its dedicatory inscriptions include the names of women who contributed to the building and were its major patrons, as well as men's names.[25] A number of buildings previously believed to have been Constantinian or 4th century have been reassessed as dating to later periods, and certain examples of 4th century basilicas are not distributed throughout the Mediterranean world at all evenly.[27] Christian basilicas and martyria attributable to the 4th century are rare on the Greek mainland and on the Cyclades, while the Christian basilicas of Egypt, Cyprus, Syria, Transjordan, Hispania, and Gaul are nearly all of later date.[27] The basilica at Ephesus's Magnesian Gate, the episcopal church at Laodicea on the Lycus, and two extramural churches at Sardis have all been considered 4th century constructions, but on weak evidence.[24] Development of pottery chronologies for Late Antiquity had helped resolve questions of dating basilicas of the period.[28]

Three examples of a basilica discoperta or "hypaethral basilica" with no roof above the nave are inferred to have existed.[29] The 6th century Anonymous pilgrim of Piacenza described a "a basilica built with a quadriporticus, with the middle atrium uncovered" at Hebron, while at Pécs and near Salona two ruined 5th buildings of debated interpretation might have been either roofless basilica churches or simply courtyards with an exedra at the end.[29] An old theory by Ejnar Dyggve that these were the architectural intermediary between the Christian martyrium and the classical heröon is no longer credited.[29]

The magnificence of early Christian basilicas reflected the patronage of the emperor and recalled his imperial palaces and reflected the royal associations of the basilica with the Hellenistic Kingdoms and even earlier monarchies like that of Pharaonic Egypt.[25] Similarly, the name and association resounded with the Christian claims of the royalty of Christ – according to the Acts of the Apostles the earliest Christians had gathered at the royal Stoa of Solomon in Jerusalem to assert Jesus's royal heritage.[25] For early Christians, the Bible supplied evidence that the First Temple and Solomon's palace were both hypostyle halls and somewhat resembled basilicas.[25] Hypostyle synagogues, often built with apses in Palestine by the 6th century, share a common origin with the Christian basilicas in the civic basilicas and in the pre-Roman style of hypostyle halls in the Mediterranean Basin, particularly in Egypt, where pre-classical hypostyles continued to be built in the imperial period and were themselves converted into churches in the 6th century.[25] Other influences on the evolution of Christian basilicas may have come from elements of domestic and palatial architecture during the pre-Constantinian period of Christianity, including the reception hall or aula (Ancient Greek:) and the atria and triclinia of élite Roman dwellings.[25] The versatility of the basilica form and its variability in size and ornament recommended itself to the early Christian Church: basilicas could be grandiose as the Basilica of Maxentius in the Forum Romanum or more practical like the so-called Basilica of Bahira in Bosra, while the Basilica Constantiniana on the Lateran Hill was of intermediate scale.[25] This basilica, begun in 313, was the first imperial Christian basilica.[25] Imperial basilicas were first constructed for the Christian Eucharist liturgy in the reign of Constantine.[26]

Basilica churches were not economically inactive. Like non-Christian or civic basilicas, basilica churches had a commercial function integral to their local trade routes and economies. Amphorae discovered at basilicas attest their economic uses and can reveal their position in wider networks of exchange.[28] At Dion near Mount Olympus in Macedonia, now an Archaeological Park, the latter 5th century Cemetery Basilica, a small church, was replete with potsherds from all over the Mediterranean, evidencing extensive economic activity took place there.[28][30] Likewise at Maroni Petrera on Cyprus, the amphorae unearthed by archaeologists in the 5th century basilica church had been imported from North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and the Aegean basin, as well as from neighbouring Asia Minor.[28][31]

According to Vegetius, writing c. 390, basilicas were convenient for drilling soldiers of the Late Roman army during inclement weather.[3]

Basilica of Maxentius

The 4th century Basilica of Maxentius, begun by Maxentius between 306 and 312 and according to Aurelius Victor's De Caesaribus completed by Constantine I, was an innovation.[32][33] Earlier basilicas had mostly had wooden roofs, but this basilica dispensed with timber trusses and used instead cross-vaults made from Roman bricks and concrete to create one of the ancient world's largest covered spaces: 80 m long, 25 m wide, and 35 m high.[3][32] The vertices of the cross-vaults, the largest Roman examples, were 35 m.[32] The vault was supported on marble monolithic columns 14.5 m tall.[32] The foundations are as much as 8 m deep.[17] The vault was supported by brick latticework ribs (Latin: bipedalis) forming lattice ribbing, an early form of rib vault, and distributing the load evenly across the vault's span.[17] Similar brick ribs were employed at the Baths of Maxentius on the Palatine Hill, where they supported walls on top of the vault.[17] Also known as the Basilica Constantiniana, 'Basilica of Constantine' or Basilica Nova, 'New Basilica', it chanced to be the last civic basilica built in Rome.[3][32]

Inside the basilica the central nave was accessed by five doors opening from an entrance hall on the eastern side and terminated in an apse at the western end.[32] Another, shallower apse with niches for statues was added to the centre of the north wall in a second campaign of building, while the western apse housed a colossal acrolithic statue of the emperor Constantine enthroned.[32] Fragments of this statue are now in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill, part of the Capitoline Museums. Opposite the northern apse on the southern wall, another monumental entrance was added and elaborated with a portico of porphyry columns.[32] One of the remaining marble interior columns was removed in 1613 by Pope Paul V and set up as an honorific column outside Santa Maria Maggiore.[32]

Constantinian period

In the early 4th century Eusebius used the word basilica (Ancient Greek:) to refer to Christian churches; in subsequent centuries as before, the word basilica referred in Greek to the civic, non-ecclesiastical buildings, and only in rare exceptions to churches.[34] Churches were nonetheless basilican in form, with an apse or tribunal at the end of a nave with two or more aisles typical.[34] A narthex (sometimes with an exonarthex) or vestibule could be added to the entrance, together with an atrium, and the interior might have transepts, a pastophorion, and galleries, but the basic scheme with clerestory windows and a wooden truss roof remained the most typical church type until the 6th century.[34] The nave would be kept clear for liturgical processions by the clergy, with the laity in the galleries and aisles to either side.[34] The function of Christian churches was similar to that of the civic basilicas but very different from temples in contemporary Graeco-Roman polytheism: while pagan temples were entered mainly by priests and thus had their splendour visible from without, within Christian basilicas the main ornamentation was visible to the congregants admitted inside.[25] Christian priests did not interact with attendees during the rituals which took place at determined intervals, whereas pagan priests were required to perform individuals' sacrifices in the more chaotic environment of the temple precinct, with the temple's facade as backdrop.[25] In basilicas constructed for Christian uses, the interior was often decorated with frescoes, but these buildings' wooden roof often decayed and failed to preserve the fragile frescoes within.[27] Thus was lost an important part of the early history of Christian art, which would have sought to communicate early Christian ideas to the mainly illiterate Late Antique society.[27] On the exterior, basilica church complexes included cemeteries, baptisteries, and fonts which "defined ritual and liturgical access to the sacred", elevated the social status of the Church hierarchy, and which complemented the development of a Christian historical landscape; Constantine and his mother Helena were patrons of basilicas in important Christian sites in the Holy Land and Rome, and at Milan and Constantinople.[27]

Around 310, while still a self-proclaimed augustus unrecognised at Rome, Constantine began the construction of the Basilica Constantiniana or Aula Palatina, 'palatine hall', as a reception hall for his imperial seat at Trier (Augusta Treverorum), capital of Belgica Prima.[3] On the exterior, Constantine's palatine basilica was plain and utilitarian, but inside was very grandly decorated.[35]

In the reign of Constantine I, a basilica was constructed for the Pope in the former barracks of the Equites singulares Augusti, the cavalry arm of the Praetorian Guard.[36] (Constantine had disbanded the Praetorian guard after his defeat of their emperor Maxentius and replaced them with another bodyguard, the Scholae Palatinae.)[36] In 313 Constantine began construction of the Basilica Constantiniana on the Lateran Hill.[25] This basilica became Rome's cathedral church, known as St John Lateran, and was more richly decorated and larger than any previous Christian structure.[25] However, because of its remote position from the Forum Romanum on the city's edge, it did not connect with the older imperial basilicas in the fora of Rome.[25] Outside the basilica was the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, a rare example of an Antique statue that has never been underground.[9]

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Constantine was also responsible for the rich interior decoration of the Lateran Baptistery constructed under Pope Sylvester I (r. 314–335), sited about 50 metres (160 ft).[26] The Lateran Baptistery was the first monumental free-standing baptistery, and in subsequent centuries Christian basilica churches were often endowed with such baptisteries.[26]

At Cirta, a Christian basilica erected by Constantine was taken over by his opponents, the Donatists.[36] After Constantine's failure to resolve the Donatist controversy by coercion between 317 and 321, he allowed the Donatists, who dominated Africa, to retain the basilica and constructed a new one for the Catholic Church.[36]

The original titular churches of Rome were those which had been private residences and which were donated to be converted to places of Christian worship.[25] Above an originally 1st century AD villa and its later adjoining warehouse and Mithraeum, a large basilica church had been erected by 350, subsuming the earlier structures beneath it as a crypt.[25] The basilica was the first church of San Clemente al Laterano.[25] Similarly, at Santi Giovanni e Paolo al Celio, an entire ancient city block – a 2nd-century insula on the Caelian Hill – was buried beneath a 4th-century basilica.[25] The site was already venerated as the martyrium of three early Christian burials beforehand, and part of the insula had been decorated in the style favoured by Christian communities frequenting the early Catacombs of Rome.[25]

By 350 in Serdica (Sofia, Bulgaria), a monumental basilica – the Church of Saint Sophia – was erected, covering earlier structures including a Christian chapel, an oratory, and a cemetery dated to c. 310.[25] Other major basilica from this period, in this part of Europe, is the Great Basilica in Philippopolis (Plovdiv, Bulgaria) from the 4th century AD.

Valentinianic–Theodosian period

In the late 4th century the dispute between Nicene and Arian Christianity came to head at Mediolanum (Milan), where Ambrose was bishop.[37] At Easter in 386 the Arian party, preferred by the Theodosian dynasty, sought to wrest the use of the basilica from the Nicene partisan Ambrose.[37] According to Augustine of Hippo, the dispute resulted in Ambrose organising an 'orthodox' sit-in at the basilica and arranged the miraculous invention and translation of martyrs, whose hidden remains had been revealed in a vision.[37] During the sit-in, Augustine credits Ambrose with the introduction from the "eastern regions" of antiphonal chanting, to give heart to the orthodox congregation, though in fact music was likely part of Christian ritual since the time of the Pauline epistles.[38][37] The arrival and reburial of the martyrs' uncorrupted remains in the basilica in time for the Easter celebrations was seen as powerful step towards divine approval.[37]

At Philippi, the market adjoining the 1st-century forum was demolished and replaced with a Christian basilica.[7] Civic basilicas throughout Asia Minor became Christian places of worship; examples are known at Ephesus, Aspendos, and at Magnesia on the Maeander.[24] The Great Basilica in Antioch of Pisidia is a rare securely dated 4th century Christian basilica and was the city's cathedral church.[24] The mosaics of the floor credit Optimus, the bishop, with its dedication.[24] Optimus was a contemporary of Basil of Caesarea and corresponded with him c. 377.[24] Optimus was the city's delegate at the First Council of Constantinople in 381, so the 70 m-long single-apsed basilica near the city walls must have been constructed around that time.[24] Pisidia had a number of Christian basilicas constructed in Late Antiquity, particularly in former bouleuteria, as at Sagalassos, Selge, Pednelissus, while a civic basilica was converted for Christians' use in Cremna.[24]

At Chalcedon, opposite Constantinople on the Bosporus, the relics of Euphemia – a supposed Christian martyr of the Diocletianic Persecution – were housed in a martyrium accompanied by a basilica.[39] The basilica already existed when Egeria passed through Chalcedon in 384, and in 436 Melania the Younger visited the church on her own journey to the Holy Land.[39] From the description of Evagrius Scholasticus the church is identifiable as an aisled basilica attached to the martyrium and preceded by an atrium.[40] The Council of Chalcedon (8–31 October 451) was held in the basilica, which must have been large enough to accommodate the more than two hundred bishops that attended its third session, together with their translators and servants; around 350 bishops attended the Council in all.[41][42] In an ekphrasis in his eleventh sermon, Asterius of Amasea described an icon in the church depicting Euphemia's martyrdom.[39] The church was restored under the patronage of the patricia and daughter of Olybrius, Anicia Juliana.[43] Pope Vigilius fled there from Constantinople during the Three-Chapter Controversy.[44] The basilica, which lay outside the walls of Chalcedon, was destroyed by the Persians in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 during one of the Sasanian occupations of the city in 615 and 626.[45] The relics of Euphemia were reportedly translated to a new Church of St Euphemia in Constantinople in 680, though Cyril Mango argued the translation never took place.[46][47] Subsequently, Asterius's sermon On the Martyrdom of St Euphemia was advanced as an argument for iconodulism at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[48]

In the late 4th century, a large basilica church dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus was constructed in Ephesus in the former south stoa (a commercial basilica) of the Temple of Hadrian Olympios.[49][50] Ephesus was the centre of the Roman province of Asia, and was the site of the city's famed Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.[51] It had also been a centre of the Roman imperial cult in Asia; Ephesus was three times declared neokoros (lit. temple-warden) and had constructed a Temple of the Sebastoi to the Flavian dynasty.[51] The Basilica of the Virgin Mary was probably the venue for the 431 Council of Ephesus and the 449 Second Council of Ephesus, both convened by Theodosius II.[49] At some point during the Christianisation of the Roman world, Christian crosses were cut into the faces of the colossal statues of Augustus and Livia that stood in the basilica-stoa of Ephesus; the crosses were perhaps intended to exorcise demons in a process akin to baptism.[9] In the eastern cemetery of Hierapolis the 5th century domed octagonal martyrium of Philip the Apostle was built alongside a basilica church, while at Myra the Basilica of St Nicholas was constructed at the tomb of Saint Nicholas.[24]

At Constantinople the earliest basilica churches, like the 5th century basilica at the Monastery of Stoudios, were mostly equipped with a small cruciform crypt (Ancient Greek:), a space under the church floor beneath the altar.[52] Typically, these crypts were accessed from the apse's interior, though not always, as at the 6th century Church of St John at the Hebdomon, where access was from outside the apse.[52] At Thessaloniki, the Roman bath where tradition held Demetrius of Thessaloniki had been martyred was subsumed beneath the 5th century basilica of Hagios Demetrios, forming a crypt.[52]

The largest and oldest basilica churches in Egypt were at Pbow, a coenobitic monastery established by Pachomius the Great in 330.[53] The 4th century basilica was replaced by a large 5th century building (36 × 72 m) with five aisles and internal colonnades of pink granite columns and paved with limestone.[53] This monastery was the administrative centre of the Pachomian order where the monks would gather twice annually and whose library may have produced many surviving manuscripts of biblical, Gnostic, and other texts in Greek and Coptic.[53] In North Africa, late antique basilicas were often built on a doubled plan.[54] In the 5th century, basilicas with two apses, multiple aisles, and doubled churches were common, including examples respectively at Sufetula, Tipasa, and Djémila.[54] Generally, North African basilica churches' altars were in the nave and the main building medium was opus africanum of local stone, and spolia was infrequently used.[54]

The Church of the East's Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon was convened by the Sasanian Emperor Yazdegerd I at his capital at Ctesiphon; according to Synodicon Orientale, the emperor ordered that the former churches in the Sasanian Empire to be restored and rebuilt, that such clerics and ascetics as had been imprisoned were to be released, and their Nestorian Christian communities allowed to circulate freely and practice openly.[55]

In eastern Syria, the Church of the East developed at typical pattern of basilica churches.[55] Separate entrances for men and women were installed in the southern or northern wall; within, the east end of the nave was reserved for men, while women and children were stood behind. In the nave was a bema, from which Scripture could be read, and which were inspired by the equivalent in synagogues and regularised by the Church of Antioch.[55] The Council of 410 stipulated that on Sunday the archdeacon would read the Gospels from the bema.[55] Standing near the bema, the lay folk could chant responses to the reading and if positioned near the šqāqonā ("a walled floor-level pathway connecting the bema to the altar area") could try to kiss or touch the Gospel Book as it was processed from the deacons' room to the bema and thence to the altar.[55] Some ten Eastern churches in eastern Syria have been investigated by thorough archaeology.[55]

A Christian basilica was constructed in the first half of the 5th century at Olympia, where the statue of Zeus by Phidias had been noted as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World ever since the 2nd century BC list compiled by Antipater of Sidon.[56][57] Cultural tourism thrived at Olympia and Ancient Greek religion continued to be practised there well into the 4th century.[56] At Nicopolis in Epirus, founded by Augustus to commemorate his victory at the Battle of Actium at the end of the Last war of the Roman Republic, four early Christian basilicas were built during Late Antiquity whose remains survive to the present.[58] In the 4th or 5th century, Nicopolis was surrounded by a new city wall.[58]

In Bulgaria there are major basilicas from that time like Elenska Basilica and the Red Church.

Leonid period

On Crete, the Roman cities suffered from repeated earthquakes in the 4th century, but between c. 450 and c. 550, a large number of Christian basilicas were constructed.[59] Crete was throughout Late Antiquity a province of the Diocese of Macedonia, governed from Thessaloniki.[59]

Nine basilica churches were built at Nea Anchialos, ancient Phthiotic Thebes (Ancient Greek:), which was in its heyday the primary port of Thessaly. The episcopal see was the three-aisled Basilica A, the Church of St Demetrius of Thessaloniki, and similar to the Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki.[60] Its atrium perhaps had a pair of towers to either side and its construction dates to the late 5th/early 6th century.[60] The Elpidios Basilica – Basilica B – was of similar age, and the city was home to a large complex of ecclesiastical buildings including Basilica G, with its luxurious mosaic floors and a mid-6th century inscription proclaiming the patronage of the bishop Peter. Outside the defensive wall was Basilica D, a 7th-century cemetery church.[60]

Stobi, (Ancient Greek:) the capital from the late 4th century of the province of Macedonia II Salutaris, had numerous basilicas and six palaces in late antiquity.[61] The Old Basilica had two phases of geometric pavements, the second phase of which credited the bishop Eustathios as patron of the renovations. A newer episcopal basilica was built by the bishop Philip atop the remains of the earlier structure, and two further basilicas were within the walls.[61] The Central Basilica replaced a synagogue on a site razed in the late 5th century, and there was also a North Basilica and further basilicas without the walls.[61] Various mosaics and sculptural decorations have been found there, and while the city suffered from the Ostrogoths in 479 and an earthquake in 518, ceasing to be a major city thereafter, it remained a bishopric until the end of the 7th century and the Basilica of Philip had its templon restored in the 8th century.[61]

The Small Basilica of Philippopolis (Plovdiv, Bulgaria) in Thrace was built in the second half of the 5th century AD.

Justinianic period

Justinian I constructed at Ephesus a large basilica church, the Basilica of St John, above the supposed tomb of John the Apostle.[51] The church was a domed cruciform basilica begun in 535/6; enormous and lavishly decorated, it was built in the same style as Justinian's Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople.[49][24] The Justinianic basilica replaced an earlier, smaller structure which Egeria had planned to visit in the 4th century, and remains of a 2,130 foot (650 m) aqueduct branch built to supply the complex with water probably dates from Justinian's reign.[49][62] The Ephesians' basilicas to St Mary and St John were both equipped with baptisteries with filling and draining pipes: both fonts were flush with the floor and unsuitable for infant baptism.[26] As with most Justinianic baptisteries in the Balkans and Asia Minor, the baptistery at the Basilica of St John was on the northern side of the basilica's nave; the 734 m2 baptistery was separated from the basilica by a 3 m-wide corridor.[26] According to the 6th century Syriac writer John of Ephesus, a Syriac Orthodox Christian, the heterodox Miaphysites held ordination services in the courtyard of the Basilica of St John under cover of night.[49] Somewhat outside the ancient city on the hill of Selçuk, the Justinianic basilica became the centre of the city after the 7th century Arab–Byzantine wars.[49]

At Constantinople, Justinian constructed the largest domed basilica: on the site of the 4th century basilica Church of Holy Wisdom, the emperor ordered construction of the huge domed basilica that survives to the present: the Hagia Sophia.[27] This basilica, which "continues to stand as one of the most visually imposing and architecturally daring churches in the Mediterranean", was the cathedral of Constantinople and the patriarchal church of the Patriarch of Constantinople.[27] Hagia Sophia, originally founded by Constantine, was at the social and political heart of Constantinople, near to the Great Palace, the Baths of Zeuxippus, and the Hippodrome of Constantinople, while the headquarters of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was within the basilica's immediate vicinity.[63]

The mid-6th century Bishop of Poreč (Latin: Parens or Parentium; Ancient Greek:) replaced an earlier 4th century basilica with the magnificent Euphrasian Basilica in the style of contemporary basilicas at Ravenna.[64] Some column capitals were of marble from Greece identical to those in Basilica of San Vitale and must have been imported from the Byzantine centre along with the columns and some of the opus sectile.[64] There are conch mosaics in the basilica's three apses and the fine opus sectile on the central apse wall is "exceptionally well preserved".[64]

The 4th century basilica of Saint Sophia Church at Serdica (Sofia, Bulgaria) was rebuilt in the 5th century and ultimately replaced by a new monumental basilica in the late 6th century, and some construction phases continued into the 8th century.[65] This basilica was the cathedral of Serdica and was one of three basilicas known to lie outside the walls; three more churches were within the walled city, of which the Church of Saint George was a former Roman bath built in the 4th century, and another was a former Mithraeum.[65] The basilicas were associated with cemeteries with Christian inscriptions and burials.[65]

Another basilica from this period in Bulgaria was the Belovo Basilica (6th century AD).

The Miaphysite convert from the Church of the East, Ahudemmeh constructed a new basilica c. 565 dedicated to Saint Sergius at ʿAin Qenoye (or ʿAin Qena according to Bar Hebraeus) after being ordained bishop of Beth Arbaye by Jacob Baradaeus and while proselytizing among the Bedouin of Arbayistan in the Sasanian Empire.[66] According to Ahudemmeh's biographer this basilica and its martyrium, in the upper Tigris valley, was supposed to be a copy of the Basilica of St Sergius at Sergiopolis (Resafa), in the middle Euphrates, so that the Arabs would not have to travel so far on pilgrimage.[66] More likely, with the support of Khosrow I for its construction and defence against the Nestorians who were Miaphysites' rivals, the basilica was part of an attempt to control the frontier tribes and limit their contact with the Roman territory of Justinian, who had agreed in the 562 Fifty-Year Peace Treaty to pay 30,000 nomismata annually to Khosrow in return for a demilitarization of the frontier after the latest phase of the Roman–Persian Wars.[66] After being mentioned in 828 and 936, the basilica at ʿAin Qenoye disappeared from recorded history, though it may have remained occupied for centuries, and was rediscovered as a ruin by Carsten Niebuhr in 1766.[67] The name of the modern site Qasr Serīj is derived from the basilica's dedication to St Sergius.[66] Qasr Serīj's construction may have been part of the policy of toleration that Khosrow and his successors had for Miaphysitism – a contrast with Justinian's persecution of heterodoxy within the Roman empire.[66] This policy itself encouraged many tribes to favour the Persian cause, especially after the death in 569 of the Ghassanid Kingdom's Miaphysite king al-Harith ibn Jabalah (Latin: Flavius Arethas, Ancient Greek:) and the 584 suppression by the Romans of his successors' dynasty.[66]

Saint Sophia, Serdica (Sofia), built 4th–8th centuries

Ostrogothic Basilica of Christ the Redeemer, Ravenna, 504. Rededicated 561 to St Apollinaris

Justinianic Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem, after 529

Ruins of the 10th-century Church of Achillius of Larissa, on the eponymous island of Agios Achilleios, Mikra Prespa, a typical basilica church[68]

Palace basilicas

In the Roman Imperial period (after about 27 BC), a basilica for large audiences also became a feature in palaces. In the 3rd century of the Christian era, the governing elite appeared less frequently in the forums.

They now tended to dominate their cities from opulent palaces and country villas, set a little apart from traditional centers of public life. Rather than retreats from public life, however, these residences were the forum made private.

- — Peter Brown, in Paul Veyne, 1987

Seated in the tribune of his basilica, the great man would meet his dependent clientes early every morning.

Constantine's basilica at Trier, the Aula Palatina (AD 306), is still standing. A private basilica excavated at Bulla Regia (Tunisia), in the "House of the Hunt", dates from the first half of the 5th century. Its reception or audience hall is a long rectangular nave-like space, flanked by dependent rooms that mostly also open into one another, ending in a semi-circular apse, with matching transept spaces. Clustered columns emphasised the "crossing" of the two axes.

Christian adoption of the basilica form

Variations: Where the roofs have a low slope, the triforium gallery may have own windows or may be missing.

In the 4th century, once the Imperial authorities had decriminalised Christianity with the 313 Edict of Milan, and with the activities of Constantine the Great and his mother Helena, Christians were prepared to build larger and more handsome edifices for worship than the furtive meeting-places (such as the Cenacle, cave-churches, house churches such as that of the martyrs John and Paul) they had been using. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable due to their pagan associations, and because pagan cult ceremonies and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a backdrop. The usable model at hand, when Constantine wanted to memorialise his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilicas.[69]

There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other end. In (and often also in front of) the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed, and from where the clergy officiated. In secular building this plan was more typically used for the smaller audience halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the great public basilicas functioning as law courts and other public purposes.[70] Constantine built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier, later very easily adopted for use as a church. It is a long rectangle two storeys high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (there was no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and, at the far end beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state.

- Comparison of cross sections of churches

Aisleless church with wallside pilasters, a barrel-vault and upper windows above lateral chapels

Development

Putting an altar instead of the throne, as was done at Trier, made a church. Basilicas of this type were built in western Europe, Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine, that is, at any early centre of Christianity. Good early examples of the architectural basilica include the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem (6th century), the church of St Elias at Thessalonica (5th century), and the two great basilicas at Ravenna.

The first basilicas with transepts were built under the orders of Emperor Constantine, both in Rome and in his "New Rome", Constantinople:

Around 380, Gregory Nazianzen, describing the Constantinian Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople, was the first to point out its resemblance to a cross. Because the cult of the cross was spreading at about the same time, this comparison met with stunning success.

- — Yvon Thébert, in Veyne, 1987

Thus, a Christian symbolic theme was applied quite naturally to a form borrowed from civil semi-public precedents. The first great Imperially sponsored Christian basilica is that of St John Lateran, which was given to the Bishop of Rome by Constantine right before or around the Edict of Milan in 313 and was consecrated in the year 324. In the later 4th century, other Christian basilicas were built in Rome: Santa Sabina, and St Paul's Outside the Walls (4th century), and later St Clement (6th century).

A Christian basilica of the 4th or 5th century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street. This was the architectural ground-plan of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, until in the 15th century it was demolished to make way for a modern church built to a new plan.

In most basilicas, the central nave is taller than the aisles, forming a row of windows called a clerestory. Some basilicas in the Caucasus, particularly those of Armenia and Georgia, have a central nave only slightly higher than the two aisles and a single pitched roof covering all three. The result is a much darker interior. This plan is known as the "oriental basilica", or "pseudobasilica" in central Europe. A peculiar type of basilica, known as three-church basilica, was developed in early medieval Georgia, characterised by the central nave which is completely separated from the aisles with solid walls.[71]

Gradually, in the Early Middle Ages there emerged the massive Romanesque churches, which still kept the fundamental plan of the basilica.

In Medieval Bulgaria the Great Basilica was finished around 875. The architectural complex in Pliska, the first capital of the First Bulgarian Empire, included a cathedral, an archbishop's palace and a monastery.[72] The basilica was one of the greatest Christian cathedrals in Europe of the time, with an area of 2,920 square metres (31,400 sq ft). The still in use Church of Saint Sophia in Ohrid is another example from Medieval Bulgaria.

In Romania, the word for church both as a building and as an institution is biserică, derived from the term basilica.

In the United States the style was copied with variances. An American church built imitating the architecture of an Early Christian basilica, St. Mary's (German) Church in Pennsylvania, was demolished in 1997.

Romanesque basilica of nowadays Lutheran Bursfelde Abbey in Germany

Chester Cathedral in England , a Gothic style basilica

Palma Cathedral on Mallorca in Spain has windows on three levels, one above the aisles, one above the file of chapels and one in the chapels.

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia

Catholic basilicas

In the Catholic Church, a basilica is a large and important church building. This designation may be made by the Pope or may date from time immemorial.[73][74] Basilica churches are distinguished for ceremonial purposes from other churches. The building does not need to be a basilica in the architectural sense. Basilicas are either major basilicas – of which there are four, all in the diocese of Rome—or minor basilicas, of which there were 1,810 worldwide (As of 2019).[75] The Umbraculum is displayed in a basilica to the right side (i.e. the Epistle side) of the altar to indicate that the church has been awarded the rank of a basilica.

See also

- Macellum – Roman covered market

- Market hall – modern covered market

- Courthouse

- Curia

- Municipal curiae

- Town hall

Architecture

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Byzantine architecture

- Church architecture

References

Citations

- ↑ Henig, Martin (ed.), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, p. 55, 1983, ISBN:0714822140; Sear, F. B., "Architecture, 1, a) Religious", section in Diane Favro, et al. "Rome, ancient." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 26 March 2016, subscription required

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Roberts, John, ed. (2007), "basilica" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-280146-3, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-314

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Dumser, Elisha Ann (2010), Gagarin, Michael, ed. (in en), Basilica, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001/acref-9780195170726-e-164

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2013 ISBN:978-0-19968027-6), p. 117

- ↑ "The Institute for Sacred Architecture – Articles – The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture". http://www.sacredarchitecture.org/articles/the_eschatological_dimension_of_church_architecture.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Donati, Jamieson C. (4 November 2014), Marconi, Clemente, ed., "The City in the Greek and Roman World", The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199783304.013.011, ISBN 978-0-19-978330-4, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199783304.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199783304-e-011

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Davis, Thomas W. (2019), Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K., eds., "New Testament Archaeology Beyond the Gospels" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology (Oxford University Press): pp. 45–63, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.013.34, ISBN 978-0-19-936904-1, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-34

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Darvill, Timothy (2009), "basilica" (in en), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-953404-3, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001/acref-9780199534043-e-400

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Kristensen, Troels Myrup (2019), Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K., eds., "Statues" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology (Oxford University Press): pp. 332–349, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.013.19, ISBN 978-0-19-936904-1, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-19

- ↑ Vitruvius, De architectura, V:1.6–10

- ↑ Hurlet, Frédéric (6 January 2015). Bruun, Christer. ed (in en). The Roman Emperor and the Imperial Family. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 178–201. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336467.013.010. ISBN 978-0-19-533646-7. http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336467.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195336467-e-010.

- ↑ Bagnani, Gilbert (1919). ""The Subterranean Basilica at Porta Maggiore."". The Journal of Roman Studies 9: 78–85. doi:10.2307/295990. https://doi.org/10.2307/295990.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Merrifield, Ralph (1983) (in en). London, City of the Romans. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 61–67. ISBN 978-0-520-04922-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=39wl2I48e7kC&pg=PA61.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Merrifield, Ralph (1983) (in en). London, City of the Romans. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 978-0-520-04922-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=39wl2I48e7kC&pg=PA63.

- ↑ Johnson, Ben. "The Remains of London's Roman Basilica and Forum" (in en-GB). https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/Londons-Roman-Basilica-Forum/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Campbell, John Brian (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Trajan" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-640

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Lancaster, Lynne (2009). "Roman Engineering and Construction". in Oleson, John Peter (in en). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734856.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734856.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199734856-e-11.

- ↑ Birley, Anthony R.; Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Hadrian" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-302

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Weech, William Nassau; Warmington, Brian Herbert; Wilson, Roger J. A. (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Carthage" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-127

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew I. (2003). "Opus reticulatum panels in the Severan Basilica at Lepcis Magna". Quaderni di Archeologia della Libya 18: 369–379. https://www.academia.edu/435555.

- ↑ Rogerson, Barnaby (2018) (in en). In Search of Ancient North Africa: A History in Six Lives. London: Haus Publishing. pp. 283. ISBN 978-1-909961-55-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=89pTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT283.

- ↑ Goodman, Martin David (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "synagogue" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-608

- ↑ Morris, Ian (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "dead, disposal of" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-194

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 24.12 Talloen, Peter (2019), Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K., eds., "Asia Minor" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology (Oxford University Press): pp. 494–513, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.013.24, ISBN 978-0-19-936904-1, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-24

- ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 25.11 25.12 25.13 25.14 25.15 25.16 25.17 25.18 25.19 25.20 25.21 25.22 25.23 25.24 25.25 Stewart, Charles Anthony (2019). "Churches". in Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K. (in en). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-8.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Rutherford, H. Richard (2019). "Baptisteries in Ancient Sites and Rites". in Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K. (in en). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-10.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 Caraher, William R.; Pettegrew, David K. (28 February 2019), Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K., eds., "The Archaeology of Early Christianity: The History, Methods, and State of a Field" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology (Oxford University Press): pp. xv–27, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.013.1, ISBN 978-0-19-936904-1, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-1

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Moore, R. Scott (2019), Caraher, William R.; Davis, Thomas W.; Pettegrew, David K., eds., "Pottery" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology (Oxford University Press): pp. 295–312, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.013.17, ISBN 978-0-19-936904-1, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-17

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Johnson, Mark J. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Basilica Discoperta" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-0669

- ↑ Fragoulis, K.; Minasidis, C.; Mentzos, A. (2014). Poulou-Papadimitriou, Natalia. ed. Pottery from the Cemetery Basilica in the Early Byzantine City of Dion. Oxford, UK: British Archaeological Reports. pp. 297–304. doi:10.30861/9781407312514. ISBN 978-1-4073-1251-4.

- ↑ Manning, Sturt W. (2002). The late Roman church at Maroni Petrera: survey and salvage excavations 1990–1997, and other traces of Roman remains in the lower Maroni Valley, Cyprus. Manning, Andrew; Eckardt, Hella. Nicosia, Cyprus: A. G. Leventis Foundation. pp. 78. ISBN 9963-560-42-3. OCLC 52303510.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 32.8 Förtsch, Reinhard (2006). "Basilica Constantiniana" (in en). Brill's New Pauly. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/basilica-constantiniana-e213290.

- ↑ Aurelius Victor, de Caesaribus, xl:26

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Johnson, Mark J.; Wilkinson, John (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Basilica" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-0668

- ↑ Thomas, Edmund (2010). "Architecture". in Barchiesi, Alessandro; Scheidel, Walter (in en). pp. 837–858. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211524.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211524.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199211524-e-054.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Davis, Raymond Peter (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Constantine I" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-174

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Perkins, Pheme (8 November 2018). "Ritual and Orthodoxy". in Uro, Risto; Day, Juliette J.; Roitto, Rikard et al. (in en). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747871.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747871.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198747871-e-41.

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, Confessiones, ix:7:15–16

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Klein, Konstantin (2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Chalcedon" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-966, retrieved 2020-07-08

- ↑ Evagrius Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, II.3: "The precinct consists of three huge structures: one is open-air, adorned with a long court and columns on all sides, and another in turn after this is almost alike in breadth and length and columns but differing only in the roof above." Whitby, Michael, ed (2000) (in en). The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus. Translated Texts for Historians 33. Liverpool University Press. pp. 63–64 & notes 24–27. doi:10.3828/978-0-85323-605-4. ISBN 978-0-85323-605-4.

- ↑ Whitby, Michael, ed (2000) (in en). The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus. Translated Texts for Historians 33. Liverpool University Press. pp. 63–64 & notes 24–27. doi:10.3828/978-0-85323-605-4. ISBN 978-0-85323-605-4.

- ↑ Papadakis, Aristeides (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Chalcedon, Council of" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-0963, retrieved 2020-07-09

- ↑ Haarer, Fiona (2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Anicia Juliana" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-271, retrieved 2020-07-09

- ↑ Neil, Bronwen (2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Vigilius" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4991, retrieved 2020-07-09

- ↑ Foss, Clive F. W. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Chalcedon" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-0962, retrieved 2020-07-09

- ↑ Bardill, Jonathan (2004) (in en). Brickstamps of Constantinople. Oxford University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-19-925522-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=YS_AAzcjdK8C&pg=PA57.

- ↑ Mango, Cyril (1999). "The Relics of St. Euphemia and the Synaxarion of Constantinople". Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottoferrata 53: 79–87.

- ↑ McEachnie, Robert (2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Asterius of Amaseia" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-508, retrieved 2020-07-08

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 Thonemann, Peter (22 March 2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Ephesus" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-1664

- ↑ Van Dam, Raymond (2008). Ashbrook Harvey, Susan. ed. The East (1): Greece and Asia Minor. Oxford University Press. pp. 323–343. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199271566.003.0017. ISBN 978-0199271566. http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199271566.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199271566-e-017.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Calder, William Moir; Cook, John Manuel; Roueché, Charlotte; Spawforth, Antony (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Ephesus" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-246

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Johnson, Mark J. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Crypt" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-1298

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Trilling, James; Kazhdan, Alexander P. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Pbow" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-4170

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Loerke, William; Kiefer, Katherine M. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "North Africa, Monuments of" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-3856

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 Walker, Joel (2012). Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald. ed. From Nisibis to Xi'an: The Church of the East in Late Antique Eurasia. Oxford University Press. pp. 994–1052. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336931.013.0031. http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336931.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195336931-e-31.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Morgan, Catherine A.; Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Olympia" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-449

- ↑ Brodersen, Kai (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Seven Wonders of the ancient world" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-581

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Purcell, Nicholas; Murray, William M. (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Nicopolis" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-439

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Laidlaw, William Allison; Nixon, Lucia F.; Price, Simon R. F. (2014), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds., Eidinow, Esther (asst ed.), "Crete, Greek and Roman" (in en), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-870677-9, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198706779.001.0001/acref-9780198706779-e-184

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Gregory, Timothy E. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Nea Anchialos" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-3728

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Kazhdan, Alexander P. (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Stobi" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-5149

- ↑ Öziş, Ünal; Atalay, Ayhan; Özdemir, Yalçın (1 December 2014). "Hydraulic capacity of ancient water conveyance systems to Ephesus" (in en). Water Supply 14 (6): 1010–1017. doi:10.2166/ws.2014.055. ISSN 1606-9749. https://iwaponline.com/ws/article/14/6/1010/28490/Hydraulic-capacity-of-ancient-water-conveyance.

- ↑ Valérian, Dominique (1 February 2013). Clark, Peter. ed. Middle East: 7th–15th Centuries. Oxford University Press. pp. 263–264. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199589531.013.0014. http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199589531.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199589531-e-14.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Kinney, Dale (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Poreč" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-4421

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Rizos, Efthymios; Darley, Rebecca (2018), Nicholson, Oliver, ed., "Serdica" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4297

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 66.5 Oates, David (1962). "Qasr Serīj: A Sixth Century Basilica in Northern Iraq". Iraq 24 (2): 78–89. doi:10.2307/4199719. ISSN 0021-0889.

- ↑ Simpson, St John (1994). "A Note on Qasr Serij" (in en). Iraq (British Institute for the Study of Iraq) 56: 149–151. doi:10.2307/4200392.

- ↑ Ćurčić, Slobodan (2005), Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed., "Church Plan Types" (in en), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-1105

- ↑ "Basilica Plan Churches". Cartage.org.lb. http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/Arts/Architec/MiddleAgesArchitectural/EarlyChristianByzantine/BasilicaPlanChurches/BasilicaPlanChurches.htm.

- ↑ Syndicus, 40

- ↑ Loosley Leeming, Emma (2018). Architecture and Asceticism: Cultural Interaction between Syria and Georgia in Late Antiquity. Texts and Studies in Eastern Christianity, Volume: 13. Brill. pp. 115–121. ISBN 978-90-04-37531-4. https://brill.com/view/title/38209?lang=en.

- ↑ "Възстановяването на Голямата базилика означава памет, родолюбие и туризъм". http://fakti.bg/kultura-art/141654-vazstanovavaneto-na-golamata-bazilika-oznachava-pamet-rodolubie-i-turizam.

- ↑ 1 CIC 1917, can. 1180 as quoted in Basilicas Historical and Canonical Development, GABRIEL CHOW HOI-YAN, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 13 May 2003 (revised 24 June 2003). "It was not until 1917 that the Code of Canon Law officially recognized de jure churches that had the immemorial custom of using the title of basilica as having such a right to the title.81 We refer to such churches as immemorial."

- ↑ The title of minor basilicas was first attributed to the church of San Nicola di Tolentino in 1783. An older minor basilica is referred to as an "immemorial basilica".

- ↑ "Basilicas in the World". 2019. http://www.gcatholic.org/churches/bas.htm.

General sources

- Krautheimer, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05294-4.

- Architecture of the basilica

- Syndicus, Eduard, Early Christian Art, Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- Basilica Porcia

- W. Thayer, "Basilicas of Ancient Rome": from Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), 1929. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press)

- Paul Veyne, ed. A History of Private Life I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, 1987

- Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador

Gietmann, G. (1913). "Basilica". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Gietmann, G. (1913). "Basilica". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- Vitruvius, a 1st-century B.C. Roman architect, on how to design a basilica

|