Earth:Winneshiek Shale

| Winneshiek Shale Stratigraphic range: Darriwilian | |

|---|---|

Winneshiek Shale strata exposed via a temporary dam (a-d) | |

| Type | Formation |

| Underlies | St. Peter Sandstone |

| Overlies | unnamed breccia unit |

| Thickness | 38 m[1] |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | shale |

| Location | |

| Region | Upper Midwest |

| Country | United States |

| Extent | Iowa |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Winneshiek County, Iowa |

| Named by | Liu et al., 2006 (as "Winneshiek Lagerstätte")[1] |

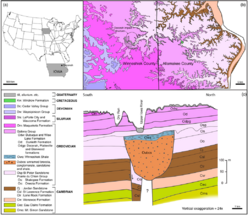

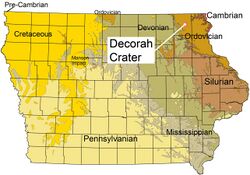

Location of the Decorah crater in Iowa, the only area where the Winneshiek Shale is found | |

The Winneshiek Shale (originally the Winneshiek Lagerstätte) is a Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian-age) geological formation in Iowa. The formation is restricted to the Decorah crater, an impact crater near Decorah, Iowa. Despite only being discovered in 2005, the Winneshiek Shale is already renowned for the exceptional preservation of its fossils. The shale preserves a unique ecosystem, the Winneshiek biota, which is among the most remarkable Ordovician lagerstätten in the United States .[2] Fossils include the oldest known eurypterid, Pentecopterus,[3] as well as giant conodonts such as Iowagnathus and Archeognathus.[4]

Geology

The Winneshiek Shale is a thin and geologically homogeneous package of dark grey to greenish-brown sandy shale. Drill core data has estimated a maximum thickness of 38 meters,[1] though in most areas its thickness is only about 18–27 meters.[3] The shale is replete with pyrite and organic carbon.[2] It lies solely within the Decorah Structure, a 5.6 km (3.5 mile)-wide probable impact crater near Decorah, Iowa. Within the crater, the shale overlies a much thicker unnamed unit mostly composed of impact breccia. The impact which formed the crater occurred after the deposition of the Shakopee Formation and before the deposition of the St. Peter Sandstone, bracketing the Winneshiek Shale between those two formations. The St. Peter Sandstone is separated from the Winneshiek Shale by an unconformity, indicating that most of the crater fill had been eroded away by the time of the sandstone's deposition.[5] This characteristic was not initially recognized, and the Winneshiek Shale was first believed to be a subunit of the St. Peter Sandstone.[1]

Apart from boreholes, the shale is only accessible at a few thin outcrops along the Upper Iowa River. A temporary dam constructed in 2010 allowed for the collection of numerous fossils from a 4-meter interval of the shale.[2] Fossils are primarily preserved as biomineralized shells or carbonaceous films, typically representative of hard parts with little soft-tissue preservation. Nevertheless, some Ceratiocaris specimens have phosphatized gut contents, and soft bromalites are preserved as apatite structures. The shale's depositional environment is reconstructed as a calm marine basin or estuary with an anoxic, low-pH seabed.[2][1]

Age and Chemostratigraphy

The Winneshiek Shale has no radiometric dating and little overlapping fossil content with nearby formations, making precise age estimates difficult. The overlying St. Peter Sandstone is firmly late Darriwilian in age based on its conodont fauna. The Winneshiek Shale shares only a few taxa with other formations, namely Multioistodus subdentatus and Archeognathus primus. Both of these conodonts were originally known from the mid- to upper-Darriwilian Dutchtown Formation of Missouri. The mid-Darriwilian global stage corresponds to the late Whiterockian regional stage in North American biostratigraphy. Conodont material similar to Iowagnathus grandis is also known from Siberia.[4]

The Darriwilian age of the Winneshiek Shale is supported by chemostratigraphy trends tabulated from drill cores. There is a gradual positive trend in organic δ13C values going up the shale. This may be correlated with the lower half of the mid-Darriwilian isotope carbon excursion (MDICE), a chemostratigraphic event observed worldwide. The MDICE is preceded by the lower-Darriwilian negative isotope carbon excursion (LDNICE), which likely occurred at the same time as the Decorah impact. Other fossil locales showing a similar negative excursion have an approximate age of around 465-467 Ma. Moreover, the Decorah impact may have occurred at the same time as numerous other mid-Ordovician impact craters in North America and around the Baltic Sea. This brief spike in asteroid impacts and meteorite abundance, the “Ordovician Meteor Event”, likely occurred due to the break up of the L-chondrite parent asteroid. It may be connected to the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), a major increase in animal diversity during the mid-Ordovician.[6]

The correlation between the MDICE and the positive excursion found in the Winneshiek Shale has been questioned. Small organic carbon isotope excursions may be influenced by local environmental or ecological conditions, rather than worldwide events. Moreover, numerous excursions occur in every time period, so there is no reason to assume that the Winneshiek record is specifically correlated with the MDICE and LDNICE. The connections between the Decorah impact, other impacts worldwide, and the GOBE have also been criticized for their reliance on imprecise age estimates.[7] Criticisms of the correlation between the MDICE and the Winneshiek excursion have been countered with the argument that alternative explanations have no direct evidence within the strata. Multioistodus subdentatus was presented as a mid-Darriwilian fossil supporting the Winneshiek Shale's biostratigraphic connection to areas with similar chemostratigraphy, despite the lack of direct biostratigraphic overlap.[8]

Paleobiota

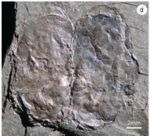

The fossil content of the Winneshiek Shale, known as the Winneshiek biota, is distinctive when compared to that of most Ordovician fossil sites. There are very few fossils of benthic animals (those which live their lives on the seabed) such as trilobites, echinoderms, brachiopods, bryozoans, or corals. Instead, the Winneshiek biota consists of nektonic animals (which swim in open waters) or nektobenthic animals (which swim close to the seabed). The most common animal remains are conodont elements and bromalites, which make up >50% and >25% of recovered fossils, respectively.[1][2] Some of the bromalites contained conodont elements, and the bromalites themselves were likely made by eurypterids or larger conodonts.[9] Other fossils include chelicerates,[3][10] bivalved crustaceans,[11][12] algae,[13] linguloid brachiopods,[1] a single gastropod specimen,[11] and head shields from armored agnathans (jawless fish).[1][2]

Arthropods

| Arthropods of the Winneshiek Shale | ||

|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Notes | Images |

| Ceratiocaris winneshiekensis[11] | A common phyllocaridan crustacean, one of the oldest ceratiocaridids | |

| Crustacea indet.[11] | An indeterminate bivalved crustacean, possibly a notostracan or Douglasocaris-like crustacean | |

| Decoracaris hildebrandi[11] | A large bivalved crustacean, possibly the oldest known thylacocephalan | |

| Iosuperstes collisionis[11] | An indeterminate bivalved crustacean | |

| Leperditiidae? indet.[11] | An indeterminate bivalved crustacean, possibly a leperditiid leperditicopidan | |

| cf. Lomatopisthia[11] | A palaeocopidan ostracod | |

| Palaeocopida indet.[11] | An indeterminate palaeocopidan ostracod | |

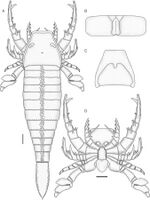

| Pentecopterus decorahensis[3] | The oldest known megalograptid eurypterid | |

| Podocopida indet.[11] | An indeterminate podocopidan ostracod | |

| Winneshiekia youngae[10] | A dekatriatan euchelicerate similar to eurypterids and chasmataspidids | |

Chordates

| Chordates of the Winneshiek Shale | ||

|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Notes | Images |

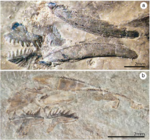

| Archeognathus primus[4] | A common giant archeognathid conodont | |

| Astraspis sp.[1] | An armored agnathan (jawless fish) | |

| Conodonta indet.[4] | Multiple unnamed or undescribed conodont taxa | |

| Iowagnathus grandis[4] | A common giant iowagnathid conodont | |

| Multioistodus subdentatus[4] | A conodont | |

Other organisms

| Other organisms of the Winneshiek Shale | ||

|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Notes | Images |

| Cladophorales indet.[13] | An unnamed large-celled filamentous algae, similar to Cladophora | |

| Gastropoda indet.[11] | An indeterminate gastropod | |

| Linguloidea indet.[1] | An indeterminate linguloid brachiopod | |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Liu, Huaibao P.; McKay, Robert M.; Young, Jean N.; Witzke, Brian J.; McVey, Kathlyn J.; Liu, Xiuying (November 2006). "A new Lagerstätte from the Middle Ordovician St. Peter Formation in northeast Iowa, USA" (in en). Geology 34 (11): 969–972. doi:10.1130/G22911A.1. ISSN 0091-7613. Bibcode: 2006Geo....34..969L.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Briggs, Derek E.G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; McKay, Robert M.; Witzke, Brian J. (24 September 2018). "The Winneshiek biota: exceptionally well-preserved fossils in a Middle Ordovician impact crater". Journal of the Geological Society 175 (6): 865–874. doi:10.1144/jgs2018-101. Bibcode: 2018JGSoc.175..865B.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (September 1, 2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. PMID 26324341.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Liu, Huaibao P.; Bergström, Stig M.; Witzke, Brian J.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; McKay, Robert M.; Ferretti, Annalisa (2017-05-01). "Exceptionally preserved conodont apparatuses with giant elements from the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Konservat-Lagerstätte, Iowa, USA" (in en). Journal of Paleontology 91 (3): 493–511. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.155. ISSN 0022-3360. Bibcode: 2017JPal...91..493L. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314154171.

- ↑ French, Bevan M.; McKay, Robert M.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Witzke, Brian J. (2018-11-01). "The Decorah structure, northeastern Iowa: Geology and evidence for formation by meteorite impact" (in en). GSA Bulletin 130 (11–12): 2062–2086. doi:10.1130/B31925.1. ISSN 0016-7606. Bibcode: 2018GSAB..130.2062F. https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/gsabulletin/article-abstract/130/11-12/2062/545187/The-Decorah-structure-northeastern-Iowa-Geology.

- ↑ Bergström, Stig M.; Schmitz, Birger; Liu, Huaibao P.; Terfelt, Fredrik; McKay, Robert M. (2018). "High-resolution δ13Corg chemostratigraphy links the Decorah impact structure and Winneshiek Konservat-Lagerstätte to the Darriwilian (Middle Ordovician) global peak influx of meteorites" (in en). Lethaia 51 (4): 504–512. doi:10.1111/let.12269. ISSN 1502-3931.

- ↑ Lindskog, Anders; Young, Seth A. (2019). "Dating of sedimentary rock intervals using visual comparison of carbon isotope records: a comment on the recent paper by Bergström et al. concerning the age of the Winneshiek Shale" (in en). Lethaia 52 (3): 299–303. doi:10.1111/let.12316. ISSN 1502-3931. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/let.12316.

- ↑ Bergström, Stig M.; Schmitz, Birger; Liu, Huaibao P.; Terfelt, Fredrik; Mckay, Robert M. (2020). "The age of the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Shale: reply to a critical review by Lindskog & Young (2019) of a paper by Bergström et al. (2018a)" (in en). Lethaia 53 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1111/let.12333. ISSN 1502-3931. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/let.12333.

- ↑ Hawkins, Andrew D.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Muscente, A. D.; Mckay, Robert M.; Witzke, Brian J.; Xiao, Shuhai (2018-01-09). "Taphonomy and Biological Affinity of Three-Dimensionally Phosphatized Bromalites from the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Lagerstätte, Northeastern Iowa, USA" (in en). PALAIOS 33 (1): 1–15. doi:10.2110/palo.2017.053. ISSN 0883-1351. Bibcode: 2018Palai..33....1H. https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/sepm/palaios/article-abstract/33/1/1/525830/TAPHONOMY-AND-BIOLOGICAL-AFFINITY-OF-THREE.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (2015-09-21). "A new Ordovician arthropod from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa (USA) reveals the ground plan of eurypterids and chasmataspidids" (in en). The Science of Nature 102 (9): 63. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1312-5. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 26391849. Bibcode: 2015SciNa.102...63L. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282127302.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; McKay, Robert M.; Witzke, Brian J. (9 May 2016). "Bivalved arthropods from the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Lagerstätte, Iowa, USA" (in en). Journal of Paleontology 89 (6): 991–1006. doi:10.1017/jpa.2015.76. ISSN 0022-3360. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-paleontology/article/abs/bivalved-arthropods-from-the-middle-ordovician-winneshiek-lagerstatte-iowa-usa/2222F0107AB10154C31525F090D85C59.

- ↑ Nowak, Hendrik; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Liu, Huaibao P.; McKay, Robert M.; Servais, Thomas (2018). "Exceptionally preserved arthropodan microfossils from the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Lagerstätte, Iowa, USA" (in en). Lethaia 51 (2): 267–276. doi:10.1111/let.12236. ISSN 1502-3931.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Nowak, Hendrik; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Liu, Huaibao P.; McKay, Robert M.; Zippi, Pierre A.; Campbell, Donald H.; Servais, Thomas (2017-08-01). "Filamentous eukaryotic algae with a possible cladophoralean affinity from the Middle Ordovician Winneshiek Lagerstätte in Iowa, USA" (in en). Geobios 50 (4): 303–309. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2017.06.005. ISSN 0016-6995. Bibcode: 2017Geobi..50..303N. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016699517300037.

|