Social:Psychological testing

| Psychological testing | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

| ICD-10-PCS | GZ1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 94.02 |

| MeSH | D011581 |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

|

|

Psychological testing refers to the administration of psychological tests.[1] Psychological tests are administered or scored by trained evaluators.[1] A person's responses are evaluated according to carefully prescribed guidelines. Scores are thought to reflect individual or group differences in the construct the test purports to measure.[1] The science behind psychological testing is psychometrics.[1][2]

Psychological tests

According to Anastasi and Urbina, psychological tests involve observations made on a "carefully chosen sample [emphasis authors] of an individual's behavior."[1] A psychological test is often designed to measure unobserved constructs, also known as latent variables. Psychological tests can include a series of tasks, problems to solve, and characteristics (e.g., behaviors, symptoms) the presence of which the respondent affirms/denies to varying degrees. Psychological tests can include questionnaires and interviews. Questionnaire- and interview-based scales typically differ from psychoeducational tests, which ask for a respondent's maximum performance. Questionnaire- and interview-based scales, by contrast, ask for the respondent's typical behavior.[3] Symptom and attitude tests are more often called scales. A useful psychological test/scale must be both valid, i.e., show evidence that the test or scale measures what it is purported to measure,[1][4]) and reliable, i.e., show evidence of consistency across items and raters and over time, etc.

It is important that people who are equal on the measured construct (e.g., mathematics ability, depression) have an approximately equal probability of answering a test item accurately or acknowledging the presence of a symptom.[5] An example of an item on a mathematics test that might be used in the United Kingdom but not the United States could be the following: "In a football match two players get a red card; how many players are left on the pitch?" This item requires knowledge of football (soccer) to be answered correctly, not just mathematical ability. Thus, group membership can influence the probability of correctly answering items, as encapsulated in the concept of differential item functioning. Often tests are constructed for a specific population and the nature of that population should be taken into account when administering tests outside that population. A test should be invariant between relevant subgroups (e.g., demographic groups) within a larger population.[6] For example, for a test to be used in the United Kingdom, the test and its items should have approximately the same meaning for British males and females. That invariance does not necessarily apply to similar groups in another population, such as males and females in the United States or between populations, for example, the populations of the UK and the US. In test construction, it is important to establish invariance at least for the subgroups of the population of interest.[6]

Psychological assessment is similar to psychological testing but usually involves a more comprehensive assessment of the individual. According to the American Psychological Association, psychological assessment involves the collection and integration of data for the purpose of evaluating an individual’s "behavior, abilities, and other characteristics."[7] Each assessment is a process that involves integrating information from multiple sources, such as personality inventories, ability tests, symptom scales, interest inventories, and attitude scales, as well as information from personal interviews. Collateral information can also be collected from occupational records or medical histories; information can also be obtained from parents, spouses, teachers, friends, or past therapists or physicians. One or more psychological tests are sources of information used within the process of assessment. Many psychologists conduct assessments when providing services. Psychological assessment is a complex, detailed, in-depth process. Examples of assessments include providing a diagnosis,[7] identifying a learning disability in schoolchildren,[8] determining if a defendant is mentally competent,[9][10] and selecting job applicants.[11]

History

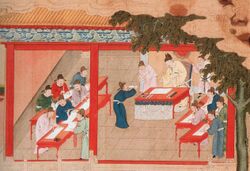

The first large-scale tests may have been part of the imperial examination system in China. The tests, an early form of psychological testing, assessed candidates based on their proficiency in topics such as civil law and fiscal policies.[12] Early tests of intelligence were made for entertainment rather than analysis.[13] Modern mental testing began in France in the 19th century. It contributed to identifying individuals with intellectual disabilities for the purpose of humanely providing them with an alternative form of education.[14]

Englishman Francis Galton coined the terms psychometrics and eugenics. He developed a method for measuring intelligence based on nonverbal sensory-motor tests. The test was initially popular but was abandoned.[14][15] In 1905 French psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon published the Échelle métrique de l'Intelligence (Metric Scale of Intelligence), known in English-speaking countries as the Binet–Simon test. The test focused heavily on verbal ability. Binet and Simon intended that the test be used to aid in identifying schoolchildren who were intellectually challenged, which in turn would pave the way for providing the children with professional help.[14] The Binet-Simon test became the foundation for the later-developed Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales.

The origins of personality testing date back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when phrenology was the basis for assessing personality characteristics. Phrenology, a pseudoscience, involved assessing personality by way of skull measurement.[16] Early pseudoscientific techniques eventually gave way to empirical methods. One of the earliest modern personality tests was the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, a self-report inventory developed during World War I to be used by the United States Army for the purpose of screening potential soldiers for mental health problems and identifying victims of shell shock (the instrument was completed too late to be used for the purposes it was designed for).[16][1] The Woodworth Inventory, however, became the forerunner of many later personality tests and scales.[1]

Principles

The development of a psychological test requires careful research. Some of the elements of test development involve the following:

- Standardization - All procedures and steps must be conducted with consistency from one testing site/testing occasion to another. Examiner subjectivity is minimized (see objectivity next). Major standardized tests are normed on large try-out samples in order to understand what constitutes high, low, and intermediate scores.

- Objectivity - Scoring such that subjective judgments and biases are minimized; scores are obtained in a similar manner for every test taker (see below).

- Discrimination - Scores on a test should discriminate members of extreme groups; for example, each subscale of the original MMPI distinguished hospitalized patients suffering from mental illness and members of a well comparison group.[17][18]

- Test Norms - Part of the standardization of large-scale tests (see above). Norms help psychologists learn about individual differences. For example, a normed personality scale can help psychologists understand how some people are high in negative affectivity (NA) and others are low or intermediate in NA. With many psychoeducational tests, test norms allow educators and psychologists obtain an age- or grade-referenced percentile rank, for example, in reading achievement.

- Reliability - Refers to test or scale consistency. It is important that individuals score about the same if they take a test and an alternate form of the test or if they take the same test twice, within a short time window. Reliability also refers to response consistency from test item to test item.

- Validity - Refers to evidence that demonstrates that a test or scale measures what it is purported to measure.[2][19]

Sample of behavior

The term sample of behavior refers to an individual's performance on tasks that have usually been prescribed beforehand. For example, a spelling test for middle school students cannot include all the words in the vocabularies of middle schoolers because there are thousands of words in their lexicon; a middle school spelling test must include only a sample of words in their vocabulary. The samples of behavior must be reasonably representative of the behavior in question. The samples of behavior that make up a paper-and-pencil test, the most common type of psychological test, are written into the test items. Total performance on the items produces a test score. A score on a well-constructed test is believed to reflect a psychological construct such as achievement in a school subject like vocabulary or mathematics knowledge, cognitive ability, dimensions of personality such as introversion/extraversion, etc. Differences in test scores are thought to reflect individual differences in the construct the test is purported to measure.[2]

Types

There are several broad categories of psychological tests:

Achievement tests

Achievement tests assess an individual's knowledge in a subject domain. Some academic achievement tests are designed to be administered by a trained evaluator. By contrast, group achievement tests are often administered by a teacher. A score on an achievement test is believed to reflect the individual's knowledge of a subject area.[1]

There are generally two types of achievement tests, norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests. Most achievement tests are norm-referenced. The individual's responses are scored according to standardized protocols and the results can be compared to the results of a norming group.[1] Norm-referenced tests can be used to underline individual differences, that is to say, to compare each test-taker to every other test-taker. By contrast, the purpose of criterion referenced achievement tests is ascertain whether the test-taker mastered a predetermined body of knowledge rather than to compare the test-taker to everyone else who took the test. These types of tests are often a component of a mastery-based classroom.[1]

The Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement is an example of an individually administered achievement test for students.[20]

Aptitude tests

Psychological tests have been designed to measure abilities, both specific (e.g., clerical skill like the Minnesota Clerical Test) and general abilities (e.g., traditional IQ tests such as the Stanford-Binet or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale). A widely used, but brief, aptitude test used in business is the Wonderlic Test. Aptitude tests have been used in assessing specific abilities or the general ability of potential new employees (the Wonderlic was once used by the NFL).[21] Aptitude tests have also been used for career guidance.[22]

Evidence suggests that aptitude tests like IQ tests are sensitive to past learning and are not pure measures of untutored ability.[23] The SAT, which used to be called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, had its named changed because performance on the test is sensitive to training.[24]

Attitude scales

An attitude scale assesses an individual's disposition regarding an event (e.g., a Supreme Court decision), person (e.g., a governor), concept (e.g., wearing face masks during a pandemic), organization (e.g., the Boy Scouts), or object (e.g., nuclear weapons) on a unidimensional favorable-unfavorable attitude continuum. Attitude scales are used in marketing to determine individuals' preferences for brands. Historically social psychologists have developed attitude scales to assess individuals' attitudes toward the United Nations and race relations.[25] Typically Likert scales are used in attitude research. Historically, the Thurstone scale was used prior to the development of the Likert scale. The Likert scale has largely supplanted the Thurstone scale.[1]

Biographical Information Blank

The Biographical Information Blanks or BIB is a paper-and-pencil form that includes items that ask about detailed personal and work history. It is used to aid in the hiring of employees by matching the backgrounds of individuals to requirements of the job.

Clinical tests

The purpose of clinical tests is to assess the presence of symptoms of psychopathology .[26] Examples of clinical assessments include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-IV,[27] Child Behavior Checklist,[28] Symptom Checklist 90[29] and the Beck Depression Inventory.[26]

Many large-scale clinical tests are normed. For example, scores on the MMPI are rescaled such that 50 is the middlemost score on the MMPI Depression scale and 60 is a score that places the individual one standard deviation above the mean for depressive symptoms; 40 represents a symptom level that is one standard deviation below the mean.[30]

Criterion-referenced

A criterion-referenced test is an achievement test in a specific knowledge domain.[1] An individual's performance on the test is compared to a criterion. Test-takers are not compared to each other. A passing score, i.e., the criterion performance, is established by the teacher or an educational institution. Criterion-referenced tests are part and parcel of mastery based education.

Direct observation

Psychological assessment can involve the observation of people as they engage in activities. This type of assessment is usually conducted with families in a laboratory or at home. Sometimes the observation can involve children in a classroom or the schoolyard.[31] The purpose may be clinical, such as to establish a pre-intervention baseline of a child's hyperactive or aggressive classroom behaviors or to observe the nature of parent-child interaction in order to understand a relational disorder.[32] Time sampling methods are also part of direct observational research. The reliability of observers in direct observational research can be evaluated using Cohen's kappa.

The Parent-Child Interaction Assessment-II (PCIA)[33] is an example of a direct observation procedure that is used with school-age children and parents. The parents and children are video recorded playing at a make-believe zoo. The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment[34] is used to study parents and young children and involves a feeding and a puzzle task. The MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB)[35] is used to elicit narratives from children. The Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System-II[36] tracks the extent to which children follow the commands of parents and vice versa and is well suited to the study of children with Oppositional Defiant Disorders and their parents.

Interest inventories

Psychological tests include interest inventories.[37] These tests are used primarily for career counseling. Interest inventories include items that ask about the preferred activities and interests of people seeking career counseling. The rationale is that if the individual's activities and interests are similar to the modal pattern of activities and interests of people who are successful in a given occupation, then the chances are high that the individual would find satisfaction in that occupation. A widely used instrument is the Strong Interest Inventory, which is used in career assessment, career counseling, and educational guidance.[38][39]

Neuropsychological tests

Neuropsychological tests are designed to assess behaviors that are linked to brain structure and function. An examiner, following strict pre-set procedures, administers the test to a single person in a quiet room largely free of distractions.[1] An example of a widely-used neuropsychological test is the Stroop test.

Norm-referenced tests

Items on norm-referenced tests have been tried out on a norming group and scores on the test can be classified as high, medium, or low and the gradations in between.[1] These tests allow for the study of individual differences. Scores on norm-referenced achievement tests are associated with percentile ranks vis-á-vis other individuals who are the test-taker's age or grade.

Personality tests

Personality tests assess constructs that are thought to be the constituents of personality. Examples of personality constructs include traits in the Big Five, such as introversion-extroversion and conscientiousness. Personality constructs are thought to be dimensional. Personality measures are used in research and in the selection of employees. They include self-report and observer-report scales.[40] Examples of norm-referenced personality tests include the NEO-PI, the 16PF Questionnaire, the Occupational Personality Questionnaires,[16] and the Five-Factor Personality Inventory.[41]

The International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) scales assess the same traits that the NEO and other personality scales assess. All IPIP scales and items are in the public domain and, therefore, are available free of charge.[42]

Projective tests

Projective testing originated in the first half of the 1900s.[43] The idea animating projective tests is that the examinee is thought to project hidden aspects of his or her personality, including unconscious content, onto the ambiguous stimuli presented in the test. Examples of projective tests include Rorschach test,[44] Thematic apperception test,[45] and the Draw-A-Person test.[46] Available evidence, however, suggests that projective tests have limited validity.[47]

Psychological symptom scales

- Bortner Type A Scale[48]

- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)[49][50]

- Children's Depression Inventory (CDI & CDI-2)[51][52]

- Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS)[53]

- General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)[54]

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7)[55]

- Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A)[56]

- Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)[57][58]

- Harburg Anger-In/Anger-Out Scale[59][60]

- Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL)[61]

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[62]

- Jenkins Activity Survey (JAS)[63] Assesses Type A/B behavior

- Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 and K10, 6- and 10-item symptom scales)[64][65]

- Midtown Study Screening Instrument[66][67]

- Multidimensional Anger Inventory (MAI)[68]

- Occupational Depression Inventory[69][70]

- Perceived Stress Scale[71]

- Patient Health Questionnaire–nine-item depression scale (PHQ-9)[72][73]

- Penn State Worry Questionnaire[74]

- Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)[75]

- Profile of Mood States (POMS)[76]

- Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI)[77]

- Psychosomatic Complaints Scale[78][79]

- Psychotic Symptoms Subscale [80]

- PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)[81]

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale[82] Although first designed for adolescents, the scale has been extensively used with adults.[83][84]

- UCLA Loneliness Scale[85][86]

- Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale[87]

- Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale[88]

Public safety employment tests

Vocations within the public safety field (e.g., fire service, law enforcement, corrections, emergency medical services) are often required to take industrial or organizational psychological tests for initial employment and promotion. The National Firefighter Selection Inventory, the National Criminal Justice Officer Selection Inventory, and the Integrity Inventory are prominent examples of these tests.[89][90][91][92]

Sources of psychological tests

Thousands of psychological tests have been developed. Some were produced by commercial testing companies that charge for their use. Others have been developed by researchers, and can be found in the academic research literature. Tests to assess specific psychological constructs can be found by conducting a database search. Some databases are open access, for example, Google Scholar (although many tests found in the Google Scholar database are not free of charge).[93] Other databases are proprietary, for example, PsycINFO, but are available through university libraries and many public libraries (e.g., the Brooklyn Public Library and the New York Public Library).[94]

There are online archives available that contain tests on various topics.

- APA PsycTests. Requires subscription[95]

- Mental Measurements Yearbook[96]- a non-profit that provides independent reviews of thousands of distinct psychological tests.

- Assessment Psychology Online has links to dozens of tests for clinical assessment.[97]

- International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) contains items to assess more than 100 personality traits including Five Factor Model.[98]

- Organization of Work: Measurement Tools for Research and Practice. NIOSH site devoted to Occupational Health and Safety[99]

Test security

Many psychological and psychoeducational tests are not available to the public. Test publishers put restrictions on who has access to the test. Psychology licensing boards also restrict access to the tests used in licensing psychologists.[100][101] Test publishers hold that both copyright and professional ethics require them to protect the tests. Publishers sell tests only to people who have proved their educational and professional qualifications. Purchasers are legally bound not to give test answers or the tests themselves to members of the public unless permitted by the publisher.[102]

The International Test Commission (ITC), an international association of national psychological societies and test publishers, publishes the International Guidelines for Test Use, which prescribes measures to take to "protect the integrity" of the tests by not publicly describing test techniques and by not "coaching individuals" so that they "might unfairly influence their test performance."[103]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Urbina, Susana; Anastasi, Anne (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 4. ISBN 9780023030857. OCLC 35450434.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Mellenbergh, G.J. (2008). Chapter 10: Surveys. In H.J. Adèr & G.J. Mellenbergh (Eds.) (with contributions by D.J. Hand), Advising on Research Methods: A consultant's companion (pp. 183-209). Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing.

- ↑ American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (1999). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- ↑ Mellenbergh, Gideon J. (1989). "Item bias and item response theory". International Journal of Educational Research 13 (2): 127–143. doi:10.1016/0883-0355(89)90002-5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Psychological assessment. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Accessed Oct. 11, 2023[1]

- ↑ Barnes, M.A., Fletcher, J., & Fuchs, L. (2007). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York: The Guilford Press.

- ↑ Neal, Tess M.S.; Mathers, Elizabeth; Frizzell, Jason R. (2022), Asmundson, Gordon J. G., ed., "Psychological Assessments in Forensic Settings" (in en), Comprehensive Clinical Psychology (Second Edition) (Oxford: Elsevier): pp. 243–257, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818697-8.00150-3, ISBN 978-0-12-822232-4, https://psyarxiv.com/5g3mj/, retrieved 2022-09-21

- ↑ Neal, Tess M.S.; Sellbom, Martin; de Ruiter, Corine (2022). "Personality Assessment in Legal Contexts: Introduction to the Special Issue". Journal of Personality Assessment 104 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1080/00223891.2022.2033248. ISSN 0022-3891. PMID 35235475. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2022.2033248.

- ↑ Board of Trustees of the Society for Personality Assessment (2006). "Standards for Education and Training in Psychological Assessment". Journal of Personality Assessment 87 (3): 355–357. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa8703_17. PMID 17134344. http://storage.jason-mohr.com/www.personality.org/General/pdf/06/SPA%20(2006,%20JPA)%20Standards%20for%20Education%20and%20Training%20in%20Assessment.pdf. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ↑ Robert J. Gregory (2003). "The History of Psychological Testing". Psychological Testing : History, Principles, and Applications. Allyn & Bacon. p. 4 in chapter 1. ISBN 9780205354726. http://www.ablongman.com/partners_in_psych/PDFs/Gregory/gregory_ch01.pdf. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ↑ Shi, Jiannong (2 February 2004). Sternberg, Robert J.. ed. International Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 330–331. ISBN 978-0-521-00402-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=qbNLJl_L6MMC&pg=PA330.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Kaufman, Alan S. (2009). IQ testing 101. Springer Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0826106292. OCLC 255892649.

- ↑ Gillham, Nicholas W. (2001). "Sir Francis Galton and the birth of eugenics". Annual Review of Genetics 35 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090055. PMID 11700278.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Nezami, Elahe; Butcher, James N. (16 February 2000). Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Elsevier. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-08-054002-3.

- ↑ Domino, George; Domino, Marla L. (2006-04-24) (in en). Psychological Testing: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34+. ISBN 978-1-139-45514-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=OiKau0aqtsYC&dq=discrimination+psychological+test&pg=PT34.

- ↑ Hogan, Thomas P. (2019) (in en). Psychological Testing: A Practical Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. pp. 171+. ISBN 978-1-119-50690-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=4AEdvwEACAAJ.

- ↑ Schultz, Duane P.; Schultz, Sydney Ellen (2010). Psychology and work today: An introduction to industrial and organizational psychology (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 99–102. ISBN 978-0205683581. OCLC 318765451.

- ↑ "Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement | Third Edition". https://www.pearsonassessments.com/store/usassessments/en/Store/Professional-Assessments/Academic-Learning/Reading/Kaufman-Test-of-Educational-Achievement-%7C-Third-Edition/p/100000777.html.

- ↑ NFL Wonderlic[2]

- ↑ Aiken, Lewis R. (1998). Tests and examinations: Measuring abilities and performance. Wiley. ISBN 9780471192633. OCLC 37820003.

- ↑ Ceci, S. J. (1991). How much does schooling influence general intelligence and its cognitive components? A reassessment of the evidence. Developmental Psychology, 27, 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.703

- ↑ Lemann, N. (1999). The big test: The secret history of the American meritocracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Brown, R. (1965). Social psychology. New York: The Free Press.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Beck, A. T.; Steer, R. A.; Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- ↑ Millon, T. (1994). Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

- ↑ Achenbach, T. M.; Rescorla, Leslie A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, Vt: ASEBA. ISBN 978-0938565734. OCLC 53902766.

- ↑ Derogatis L. R. (1983). SCL90: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual for the Revised Version. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

- ↑ Ben-Porath, Y.-S., Tellegen, A. (2011). Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory Manual of Administration-2-RF. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- ↑ Reid, J. B., Eddy, J. M., Fetrow, R. A., & Stoolmiller, M. (1999). Description and immediate impacts of a preventive intervention for conduct problems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 483–517.

- ↑ Waters, E., & Deane, K.E. (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood (pp. 41-65)Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 41-65.

- ↑ Holigrocki, R. J; Kaminski, P. L.; Frieswyk, S. H. (1999). "Introduction to the Parent-Child Interaction Assessment". Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 63 (3): 413–428. PMID 10452199.

- ↑ Clark, R (1999). "The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: A Factorial Validity Study". Educational and Psychological Measurement 59 (5): 821–846. doi:10.1177/00131649921970161.

- ↑ Bretherton, I., Oppenheim, D., Buchsbaum, H., Emde, R. N., & the MacArthur Narrative Group. (1990). MacArthur Story-Stem battery. Unpublished manual.

- ↑ Robinson, Elizabeth A.; Eyberg, Sheila M. (1981). "The dyadic parent–child interaction coding system: Standardization and validation.". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 49 (2): 245–250. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.49.2.245. PMID 7217491.

- ↑ Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Donnay, D.A.C. (1997). E.K. Strong's legacy and beyond: 70 years of the Strong Interest Inventory. The Career Development Quarterly, 46(1), 2–22. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00688.x

- ↑ Blackwell, T., & Case, J. (2008|). Test Review - Strong Interest Inventory, Revised Edition. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 51(2), 122–26, doi:10.1177/0034355207311350

- ↑ Ashton, M. C., (2017). Individual Differences and Personality (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- ↑ Jolijn Hendriks, A.a., Hofstee, W.K.B, & De Raad, B. (1999). The Five-Factor Personality Inventory (FFPI). Personality and Individual Differences, 27(2), 307-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00245-1

- ↑ International Personality Item Pool. [3] Accessed July 14, 2020

- ↑ John D., Wasserman (2003). "Nonverbal Assessment of Personality and Psychopathology". in McCallum, Steve R.. Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment. New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-47715-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=_Z_rgY-Qb-sC&q=nonverbal+%22personality+and+psychopathology%22&pg=PA283. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ Meyer, G.J., Hilsenroth, M.J., Baxter, D, Exner, J.E., Fowler, J. C., Piers, C.C., Resnick J. (2002). An examination of interrater reliability for scoring the Rorschach comprehensive system in eight data sets. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78(2), 219–274. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA7802_03.

- ↑ Murray, H. (1943). The Thematic Apperception Technique. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 223083.

- ↑ Murray, Henry A. (1943). Thematic Apperception Test manual.. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 223083.

- ↑ Lilienfeld, S.O., Wood, J.M., & Garb, H.N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1(2), 27–66. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.002. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.002

- ↑ Bortner, R.W., Gallacher, J.E.J., Sweetnam, P.M., Yarnell, J.W.G., Elwood, P.C., & Stansfeld, S.A. (2003). Bortner Type A Scale. Psychosomatic Medicine. 65, 339-346.

- ↑ Radloff, L.S.(1977).The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

- ↑ Cole, J. C., Rabin, A. S., Smith, T. L., & Kaufman, A. S. (2004). Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychological Assessment, 16, 360 –372. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360

- ↑ Kovacs, M. (1992). Children's Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems

- ↑ Kovacs, M. (2014). Children's Depression Inventory, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

- ↑ Lovibond, S.H., & Lovibond, P.F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd. Ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

- ↑ Goldberg, D.P. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Maudsley Monograph No. 21. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- ↑ Hamilton, M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32, 50–55. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

- ↑ Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23(1), 56–62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

- ↑ Hamilton, M. (1980). Rating depressive patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 41(12 Pt 2), 21–24.

- ↑ Harburg, E., Erfurt, J.C., Hauenstein, L.S., Chape, C., Schull, W.J., & Schork, M.A. (1973). Socio-ecological stress, suppressed hostility, skin color, and black-white male blood pressure: Detroit. Psychosomatic Medicine, 35, 276–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.293

- ↑ Harburg, E., Blakelock, E. H., & Roeper, P. J. (1979). Resentful and reflective coping with arbitrary authority and blood pressure: Detroit. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00002

- ↑ Derogatis, L.R., Lipman, R.S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E.H. & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1-15.

- ↑ Zigmond, A.S., & Smith, R.P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361-370.

- ↑ Jenkins, D.C., Hames, C.G., Zyanski, S.J., Rosenman, R.H., & Friedman, M. (1969). Psychological traits and serum lipids. Psychosomatic Medicine, 31(2), 115–128. doi:10.1097/00006842-196903000-00004

- ↑ Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. T.,... Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. ‘’Psychological Medicine, 32’’, 959 –976. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0033291702006074

- ↑ Furukawa, T.A., Kessler, R.C., Slade, T., & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine, 33(2), 357-362. doi:10.1017/s0033291702006700.

- ↑ Langner, T.S. (1962). A twenty-two item screening score of psychiatric symptoms indicating impairment. Journal of Health and Human Behaviour 3, 269-276.

- ↑ Srole, L., Langner, T.S., Michael, S.T., Opler, M.K. & Rennie, T.A.C. (1962). Mental health in the metropolis. McGraw-Hill: New York.

- ↑ Siegel, J.M. (1986). The Multidimensional Anger Inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(1), 191-200.

- ↑ Bianchi, R., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2020). The Occupational Depression Inventory: A new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 138, Article 110249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110249

- ↑ Schonfeld, I. S., & Bianchi, R. (2022). Distress in the workplace: Characterizing the relationship of burnout measures to the Occupational Depression Inventory. International Journal of Stress Management, 29, 253-259. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000261

- ↑ Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404

- ↑ Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., & Williams, J.B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- ↑ Kroenke, K. & Spitzer, R.L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32, 509-515.

- ↑ Stöber, J., & Bittencourt, J. (1998). Weekly assessment of worry: an adaptation of the Penn state worry questionnaire for monitoring changes during treatment. ‘’Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36’’(6), 645–656. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00031-X

- ↑ Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- ↑ Lorr, M., McNair, D. M., & Fisher, S. (1982). Evidence for bipolar mood states. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46(4), 432–436. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4604_16

- ↑ Dohrenwend, B.P., Shrout, P.E., Ergi, G.E. & Mendelsohn, F.S. (1980). Measures of non-specic psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 37, 1229-1236.

- ↑ Fried, Y., & Tiegs, R. B. (1993). The main effect model versus buffering model of shop steward social support: A study of rank-and-file auto workers in the USA. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(5), 481–493. doi:10.1002/job.4030140509

- ↑ Caplan, R. D., Cobb, S., French, J. R. P., Harrison, R. V., & Pinneau, S. R. (1980). Job demands and worker health: Main effects and occupational differences. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Mojtabai, R., Corey-Lisle, P. K., Ip, E. H.-S., Kopeykina, I., Haeri, S., Cohen, L. J., Shumaker, S., Mojtabai, R., Corey-Lisle, P. K., Ip, E. H.-S., Kopeykina, I., Haeri, S., Cohen, L. J., & Shumaker, S. (2012). Psychotic Symptoms Subscale. [Subscale from: Patient Assessment Questionnaire]. Psychiatry Research, 200(2-3), 857–866.

- ↑ Weathers, F.W., Litz, B.T., Keane, T.M., Palmieri, P.A., Marx, B.P., & Schnurr, P.P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- ↑ Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- ↑ Spector, P.E., & Jex, S.M. (1995). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,3(4), 356-367. doi:10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.356

- ↑ Low, C. A., Matthews, K. A., Kuller, L. H., & Edmundowicz, D. (2011). Psychosocial predictors of coronary artery calcification progression in postmenopausal women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(9), 789–794. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318236b68a

- ↑ Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

- ↑ Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- ↑ Zung, W. W. (1971). A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics, 12, 371–379.

- ↑ Zung, W. W. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12, 63–70. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008

- ↑ Public Safety Self Assessment. National Testing Network. [4]

- ↑ National Firefighter Selection Inventory Technical Report, 2011, I/O Solutions, Inc., Westchester, Illinois 60154 [5]

- ↑ National Criminal Justice Officer Selection Inventory Squared [6]

- ↑ Integrity Inventory [7]

- ↑ "Home". https://scholar.google.com/.

- ↑ "APA PsycInfo". https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/.

- ↑ "APA PsycTests". https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psyctests/.

- ↑ Carlson, Janet (2022). "Mental Measurements Yearbook". https://buros.org/mental-measurements-yearbook.

- ↑ "Psychological Test List". http://www.assessmentpsychology.com/testlist.htm.

- ↑ "Home". https://ipip.ori.org/.

- ↑ "Organization of Work | NIOSH | CDC". 15 October 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/workorg/.

- ↑ The Committee on Psychological Tests and Assessment (CPTA), American Psychological Association (1994). "Statement on the Use of Secure Psychological Tests in the Education of Graduate and Undergraduate Psychology Students". American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/science/securetests.html. "It should be recognized that certain tests used by psychologists and related professionals may suffer irreparable harm to their validity if their items, scoring keys or protocols, and other materials are publicly disclosed."

- ↑ Kenneth R. Morel (2009-09-24). "Test Security in Medicolegal Cases: Proposed Guidelines for Attorneys Utilizing Neuropsychology Practice". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 24 (7): 635–646. doi:10.1093/arclin/acp062. PMID 19778915.

- ↑ Pearson Assessments (2009). "Legal Policies". Psychological Corporation. https://psychcorp.pearsonassessments.com/hai/Templates/Generic/NoBoxTemplate.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7b94E55B33-4F2E-4ABC-A2E0-9842926A478F%7d&NRORIGINALURL=%2fpai%2fca%2flegal%2flegal%2ehtm&NRCACHEHINT=NoModifyGuest#release.

- ↑ International Test Commission (2000) International Guidelines for Test Use

External links

- American Psychological Association webpage on testing and assessment

- British Psychological Society Psychological Testing Centre

- Guidelines of the International Test Commission

- International Item Pool, an alternative and free source of items available for research on personality

- List of mental health tests - a web directory with links to many assessments related to mental health and substance abuse

|