Chemistry:Mitsunobu reaction

| Mitsunobu reaction | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Oyo Mitsunobu |

| Reaction type | Coupling reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | mitsunobu-reaction |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000034 |

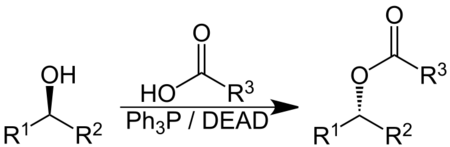

The Mitsunobu reaction is an organic reaction that converts an alcohol into a variety of functional groups, such as an ester, using triphenylphosphine and an azodicarboxylate such as diethyl azodicarboxylate (DEAD) or diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD).[1] Although DEAD and DIAD are most commonly used, there are a variety of other azodicarboxylates available which facilitate an easier workup and/or purification and in some cases, facilitate the use of more basic nucleophiles. It was discovered by Oyo Mitsunobu (1934–2003). In a typical protocol, one dissolves the alcohol, the carboxylic acid, and triphenylphosphine in tetrahydrofuran or other suitable solvent (e.g. diethyl ether), cool to 0 °C using an ice-bath, slowly add the DEAD dissolved in THF, then stir at room temperature for several hours.[2] The alcohol reacts with the phosphine to create a good leaving group then undergoes an inversion of stereochemistry in classic SN2 fashion as the nucleophile displaces it. A common side-product is produced when the azodicarboxylate displaces the leaving group instead of the desired nucleophile. This happens if the nucleophile is not acidic enough (pKa larger than 13) or is not nucleophilic enough due to steric or electronic constraints. A variation of this reaction utilizing a nitrogen nucleophile is known as a Fukuyama–Mitsunobu.

Several reviews have been published.[3][4][5][6][7]

Reaction mechanism

The reaction mechanism of the Mitsunobu reaction is fairly complex. The identity of intermediates and the roles they play has been the subject of debate.

Initially, the triphenyl phosphine (2) makes a nucleophilic attack upon diethyl azodicarboxylate (1) producing a betaine intermediate 3, which deprotonates the carboxylic acid (4) to form the ion pair 5. The formation of the ion pair 5 is very fast.

The second phase of the mechanism is proposed to be phosphorus-centered, the DEAD having been converted to the hydrazine. The ratio and interconversion of intermediates 8–11 depend on the carboxylic acid pKa and the solvent polarity.[8][9][10] Although several phosphorus intermediates are present, the attack of the carboxylate anion upon intermediate 8 is the only productive pathway forming the desired product 12 and triphenylphosphine oxide (13).

The formation of the oxyphosphonium intermediate 8 is slow and facilitated by the alkoxide. Therefore, the overall rate of reaction is controlled by carboxylate basicity and solvation.[11]

Order of addition of reagents

The order of addition of the reagents of the Mitsunobu reaction can be important. Typically, one dissolves the alcohol, the carboxylic acid, and triphenylphosphine in tetrahydrofuran or other suitable solvent (e.g. diethyl ether), cool to 0 °C using an ice-bath, slowly add the DEAD dissolved in THF, then stir at room temperature for several hours. If this is unsuccessful, then preforming the betaine may give better results. To preform the betaine, add DEAD to triphenylphosphine in tetrahydrofuran at 0 °C, followed by the addition of the alcohol and finally the acid.[12]

Variations

Other nucleophilic functional groups

Many other functional groups can serve as nucleophiles besides carboxylic acids. For the reaction to be successful, the nucleophile must have a pKa less than 15.

| Nucleophile | Product |

|---|---|

| hydrazoic acid | alkyl azide |

| imide | substituted imide[13] |

| phenol | alkyl aryl ether (discovered independently [14][15]) |

| sulfonamide | substituted sulfonamide[16] |

| arylsulfonylhydrazine | alkyldiazene (subject to pericyclic or free radical dediazotization to give allene (Myers allene synthesis) or alkane (Myers deoxygenation), respectively)[17] |

Modifications

Several modifications to the original reagent combination have been developed in order to simplify the separation of the product and avoid production of so much chemical waste. One variation of the Mitsunobu reaction uses resin-bound triphenylphosphine and uses di-tert-butylazodicarboxylate instead of DEAD. The oxidized triphenylphosphine resin can be removed by filtration, and the di-tert-butylazodicarboxylate byproduct is removed by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid.[18] Bruce H. Lipshutz has developed an alternative to DEAD, di-(4-chlorobenzyl)azodicarboxylate (DCAD) where the hydrazine by-product can be easily removed by filtration and recycled back to DCAD.[19]

A modification has also been reported in which DEAD can be used in catalytic versus stoichiometric quantities, however this procedure requires the use of stoichiometric (diacetoxyiodo)benzene to oxidise the hydrazine by-product back to DEAD.[20]

Denton and co-workers have reported a redox-neutral variant of the Mitsunobu reaction which employs a phosphorus(III) catalyst to activate the substrate, ensuring inversion in the nucleophilic attack, and uses a Dean-Stark trap to remove the water by-product.[21]

Phosphorane reagents

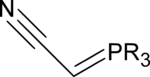

Tsunoda et al. have shown that one can combine the triphenylphosphine and the diethyl azodicarboxylate into one reagent: a phosphorane ylide. Both (cyanomethylene)trimethylphosphorane (CMMP, R = Me) and (cyanomethylene)tributylphosphorane (CMBP, R = Bu) have proven particularly effective.[22]

The ylide acts as both the reducing agent and the base. The byproducts are acetonitrile (6) and the trialkylphosphine oxide (8).

Uses

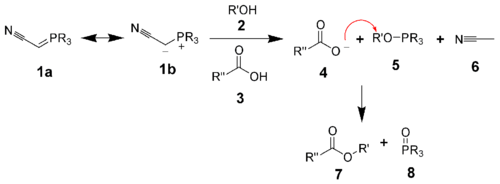

The Mitsunobu reaction has been applied in the synthesis of aryl ethers:[23]

With these particular reactants the conversion with DEAD fails because the hydroxyl group is only weakly acidic. Instead the related 1,1'-(azodicarbonyl)dipiperidine (ADDP) is used of which the betaine intermediate is a stronger base. The phosphine is a polymer-supported triphenylphosphine (PS-PPh3).

The reaction has been used to synthesize quinine, colchicine, sarain, morphine, stigmatellin, eudistomin, oseltamivir, strychnine, and nupharamine.[24]

References

- ↑ Mitsunobu, O.; Yamada, Y. (1967). "Preparation of Esters of Carboxylic and Phosphoric Acid via Quaternary Phosphonium Salts". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 40 (10): 2380–2382. doi:10.1246/bcsj.40.2380.

- ↑ "Organic Syntheses Procedure" (in en). http://orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv9p0607.

- ↑ Mitsunobu, O. (1981). "The Use of Diethyl Azodicarboxylate and Triphenylphosphine in Synthesis and Transformation of Natural Products". Synthesis 1981 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1055/s-1981-29317.

- ↑ Castro, B. R. (1983). "Replacement of Alcoholic Hydroxyl Groups by Halogens and Other Nucleophiles via Oxyphosphonium Intermediates". Replacement of Alcoholic Hydroxy Groups by Halogens and Other Nucleophiles via Oxyphosphonium Intermediates. 29. 1–162. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or029.01. ISBN 9780471264187.

- ↑ Hughes, D. L. (1992). "The Mitsunobu Reaction". Organic Reactions. 42. pp. 335–656. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or042.02. ISBN 9780471264187.

- ↑ Hughes, D. L. (1996). "Progress in the Mitsunobu Reaction. A Review". Organic Preparations and Procedures International 28 (2): 127–164. doi:10.1080/00304949609356516.

- ↑ Swamy, K. C. K.; Kumar, N. N. B.; Balaraman, E.; Kumar, K. V. P. P. (2009). "Mitsunobu and Related Reactions: Advances and Applications". Chemical Reviews 109 (6): 2551–2651. doi:10.1021/cr800278z. PMID 19382806.

- ↑ Grochowski, E.; Hilton, B. D.; Kupper, R. J.; Michejda, C. J. (1982). "Mechanism of the triphenylphosphine and diethyl azodicarboxylate induced dehydration reactions (Mitsunobu reaction). The central role of pentavalent phosphorus intermediates". Journal of the American Chemical Society 104 (24): 6876–6877. doi:10.1021/ja00388a110.

- ↑ Camp, D.; Jenkins, I. D. (1989). "The mechanism of the Mitsunobu esterification reaction. Part I. The involvement of phosphoranes and oxyphosphonium salts". The Journal of Organic Chemistry 54 (13): 3045–3049. doi:10.1021/jo00274a016.

- ↑ Camp, D.; Jenkins, I. D. (1989). "The mechanism of the Mitsunobu esterification reaction. Part II. The involvement of (acyloxy)alkoxyphosphoranes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry 54 (13): 3049–3054. doi:10.1021/jo00274a017.

- ↑ Hughes, D. L.; Reamer, R. A.; Bergan, J. J.; Grabowski, E. J. J. (1988). "A mechanistic study of the Mitsunobu esterification reaction". Journal of the American Chemical Society 110 (19): 6487–6491. doi:10.1021/ja00227a032.

- ↑ Volante, R. (1981). "A new, highly efficient method for the conversion of alcohols to thiolesters and thiols". Tetrahedron Letters 22 (33): 3119–3122. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81842-6.

- ↑ Hegedus, L. S.; Holden, M. S.; McKearin, J. M. (1984). "cis-N-TOSYL-3-METHYL-2-AZABICYCLO[3.3.0]OCT-3-ENE". Organic Syntheses 62: 48. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv7p0501.; Collective Volume, 7, pp. 501

- ↑ Manhas, Maghar S.; Hoffman, W. H.; Lal, Bansi; Bose, Ajay K. (1975). "Steroids. Part X. A convenient synthesis of alkyl aryl ethers". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 (5): 461–463. doi:10.1039/P19750000461.

- ↑ Bittner, Shmuel; Assaf, Yonit (1975). "Use of activated alcohols in the formation of aryl ethers". Chemistry & Industry (6): 281.

- ↑ Kurosawa, W.; Kan, T.; Fukuyama, T. (2002). "PREPARATION OF SECONDARY AMINES FROM PRIMARY AMINES VIA 2-NITROBENZENESULFONAMIDES: N-(4-METHOXYBENZYL)-3-PHENYLPROPYLAMINE". Organic Syntheses 79: 186. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=V79P0186.; Collective Volume, 10, pp. 482.

- ↑ Myers, Andrew G.; Zheng, Bin (1996). "New and Stereospecific Synthesis of Allenes in a Single Step from Propargylic Alcohols" (in en). Journal of the American Chemical Society 118 (18): 4492–4493. doi:10.1021/ja960443w. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ↑ Pelletier, J. C.; Kincaid, S. (2000). "Mitsunobu reaction modifications allowing product isolation without chromatography: application to a small parallel library". Tetrahedron Letters 41 (6): 797–800. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)02214-5.

- ↑ Lipshutz, B. H.; Chung, D. W.; Rich. B.; Corral, R. (2006). "Simplification of the Mitsunobu Reaction. Di-p-chlorobenzyl Azodicarboxylate: A New Azodicarboxylate". Organic Letters 8 (22): 5069–5072. doi:10.1021/ol0618757. PMID 17048845.

- ↑ But, T. Y.; Toy, P. H. (2006). "Organocatalytic Mitsunobu Reactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society 128 (30): 9636–9637. doi:10.1021/ja063141v. PMID 16866510.

- ↑ Beddoe, Rhydian H.; Andrews, Keith G.; Magné, Valentin; Cuthbertson, James D.; Saska, Jan; Shannon-Little, Andrew L.; Shanahan, Stephen E.; Sneddon, Helen F. et al. (2019-08-30). "Redox-neutral organocatalytic Mitsunobu reactions" (in en). Science 365 (6456): 910–914. doi:10.1126/science.aax3353. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31467220. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365..910B.

- ↑ Tsunoda, T.; Nagino, C.; Oguri, M.; Itô, S. (1996). "Mitsunobu-type alkylation with active methine compounds". Tetrahedron Letters 37 (14): 2459–2462. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(96)00318-8.

- ↑ Humphries, P. S.; Do, Q. Q. T.; Wilhite, D. M. (2006). "ADDP and PS-PPh3: an efficient Mitsunobu protocol for the preparation of pyridine ether PPAR agonists". Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2 (21): 21. doi:10.1186/1860-5397-2-21. PMID 17076898.

- ↑ Mitsunobu Reaction at SynArchive Accessed 26 April 2014

See also

|