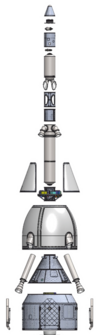

Astronomy:Launch escape system

A launch escape system (LES) or launch abort system (LAS) is a crew-safety system connected to a space capsule. It is used in the event of a critical emergency to quickly separate the capsule from its launch vehicle in case of an emergency requiring the abort of the launch, such as an impending explosion. The LES is typically controlled by a combination of automatic rocket failure detection, and a manual activation for the crew commander's use. The LES may be used while the launch vehicle is still on the launch pad, or during its ascent. Such systems are usually of three types:

- A solid-fueled rocket, mounted above the capsule on a tower, which delivers a relatively large thrust for a brief period of time to send the capsule a safe distance away from the launch vehicle, at which point the capsule's parachute recovery system can be used for a safe landing on ground or water. The escape tower and rocket are jettisoned from the space vehicle in a normal flight at the point where it is either no longer needed, or cannot be effectively used to abort the flight. These have been used on the Mercury, Apollo, Soyuz, and Shenzhou capsules.

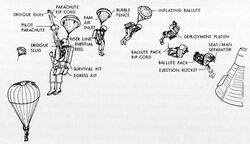

- The crew are seated in seats that eject themselves (ejection seats) as used in military aircraft; each crew member returns to Earth with an individual parachute. Such systems are effective only in a limited range of altitudes and speeds. These have been used on the Vostok and Gemini capsules, and Space Shuttle Columbia during its testing phase.

Diagram of Gemini's launch escape sequence

Diagram of Gemini's launch escape sequence - Thrusters integrated in the capsule or its detachable service module having the same function as an escape tower, as in the case of Crew Dragon, Starliner and New Shepard.

History

The idea of using a rocket to remove the capsule from a space vehicle was developed by Maxime Faget in 1958.[1] The system, using the tower on the top of the space capsule to house rockets, was first used on a test of the Project Mercury capsule in March 1959. Historically, LES were used on American Mercury and Apollo spacecraft. Both designs used a solid-fuel rocket motor. The Mercury LES was built by the Grand Central Rocket Company in Redlands, California (which later became the Lockheed Propulsion Company). Apollo used a design that had many similarities to the Mercury system. LES continue to be used on the Russian Soyuz and Chinese Shenzhou spacecraft. The SpaceX designed Dragon 2 uses a hypergolic liquid-fueled launch abort system integrated to the capsule and the Boeing Starliner uses abort thrusters in its service module.

Related systems

The Soviet Vostok and American Gemini spacecraft both made use of ejection seats. The European Space Agency's Hermes and the Soviet Buran-class spaceplanes would also have made use of them if they had ever flown with crews. As shown by Soyuz T-10a, a LES must be able to carry a crew compartment from the launch pad to a height sufficient for its parachutes to open. Consequently, they must make use of large, powerful (and heavy) solid rockets. The Soyuz launch escape system is called CAC or SAS, from the Russian/transliterated Russian Система Аварийного Спасения or Sistema Avariynogo Spaseniya, meaning emergency rescue system.[2]

The Soviet Proton launcher has flown dozens of times with an escape tower, under the Zond program and the TKS program.[citation needed] All of its flights were uncrewed.

The Space Shuttle was fitted with ejection seats for the two pilots in the initial test flights, but these were removed once the vehicle was deemed operational and carried additional crew members,[3] which could not be provided with escape hatches. Following the 1986 Challenger disaster, all surviving orbiters were fitted to allow for crew evacuation through the main ingress/egress hatch (using a specially developed parachute system that could be worn over a spacesuit),[3] although only when the Shuttle was in a controlled glide.

The Orion spacecraft which was developed to follow the Space Shuttle program uses a Mercury and Apollo-style escape rocket system, while an alternative system, called the Max Launch Abort System (MLAS),[4] was investigated and would have used existing solid-rocket motors integrated into the bullet-shaped protective launch shroud.

Under NASA's Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program Blue Origin was awarded $3.7 million for development of an innovative 'pusher' LAS, it is used on the New Shepard Crew Capsule.[5]

Also under NASA's CCDev program, SpaceX was awarded $75 million for the development of their own version of a "pusher" LAS.[6] Their Dragon 2 spacecraft uses its SuperDraco engines during a launch abort scenario. Although often referred to as a "pusher" arrangement since it lacks a tower, the Dragon 2 LAS removes both the capsule and its trunk together from the launch vehicle. The system is designed to abort with the SuperDraco engines at the top of the abort stack as occurs with a more traditional tractor LAS. The concept was first tested in a Pad Abort test conducted at SLC-40, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station , on May 6, 2015.[7] SpaceX tested the system on January 19, 2020 during a full-scale simulation of a Falcon 9 rocket malfunction at Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39, from where it has later launched crews to the International Space Station.[8]

The second crewed spacecraft selected by NASA for its CCDEV program was Boeing's CST-100 Starliner, which, like SpaceX's Dragon 2 spacecraft, uses a "pusher" launch escape system, consisting of four launch abort engines mounted on the service module that can propel the spacecraft away from its Atlas V launch vehicle in the event of an emergency on the pad or during ascent.[9] The engines, which use hypergolic propellants and generate 40,000 pounds-force of thrust each, are provided by Aerojet Rocketdyne.[10] The abort system was tested successfully during the Starliner's pad abort test on November 4, 2019 at White Sands Missile Range.[11]

Orbital Sciences Corporation intends[when?] to sell the LAS it was building for the Orion spacecraft to future commercial crew vehicle providers in the wake of the cancellation of the Constellation project.[12]

Usage

During the Mercury-Redstone 1 mission on November 21, 1960, the escape system unintentionally blasted off from the Mercury spacecraft after the Redstone booster engine shut down just after ignition on the pad. The spacecraft remained attached to the booster on the ground.

An accidental pad firing of a launch escape system occurred during the attempted launch of the uncrewed Soyuz 7K-OK No.1 spacecraft on December 14, 1966. The vehicle's strap-on boosters did not ignite, preventing the rocket from leaving the pad. About 30 minutes later, while the vehicle was being secured, the LES engine fired. Separation charges started a fire in the rocket's third stage, leading to an explosion that killed a pad worker. During the attempted launch, the booster switched from external to internal power as it normally would do, which then activated the abort sensing system. Originally it was thought that the LES firing was triggered by a gantry arm that tilted the rocket past 7 degrees, meeting one of the defined in-flight abort conditions.[13]

The first usage with a crewed mission occurred during the attempt to launch Soyuz T-10-1 on September 26, 1983.[citation needed] The rocket caught fire, just before launch, and the LES carried the crew capsule clear, seconds before the rocket exploded. The crew were subjected to an acceleration of 14 to 17 g (140 to 170 m/s2) for five seconds and were badly bruised. Reportedly, the capsule reached an altitude of 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) and landed 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) from the launch pad.

On October 11, 2018 the crew of Soyuz MS-10 separated from their launch vehicle after a booster rocket separation failure occurred at an altitude of 50 km during the ascent. However, at this point in the mission the LES had already been ejected and was not used to separate the crew capsule from the rest of the launch vehicle. Backup motors were utilized to separate the crew capsule resulting in the crew landing safely and uninjured approximately 19 minutes after launch.

On September 12, 2022 during Blue Origin New Shepard flight NS-23, the booster's BE-3 engine suffered a failure at about 1 minute into the flight. The launch escape system was triggered and the capsule successfully separated and landed nominally. The flight was carrying microgravity scientific payloads in the crew capsule, without crew on board.[14]

See also

- Flight termination system

- Apollo abort modes

- Soyuz abort modes

- Pad Abort Test 1 - Launch Escape System (LES) abort test from launch pad with Apollo Boilerplate BP-6.

- Pad Abort Test 2 - LES pad abort test of near Block-I CM with Apollo Boilerplate B-23A.

- ISRO Pad Abort Test - pad abort test of ISRO crew module

- Crew Dragon In-Flight Abort Test - Launch Abort test for the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule and Falcon 9.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ↑ "astronautix Escape Tower". http://astronautix.com/craft/mertower.htm.

- ↑ McHale, Suzy. "Soyuz launch escape system - RuSpace". http://suzymchale.com/ruspace/soyescape.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Magazine, Smithsonian; Betancourt, Mark. "They Said It Wasn't Possible to Escape the Space Shuttle. These Guys Showed It Was." (in en). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/escape-speeding-shuttle-180975606/.

- ↑ NASA Spaceflight: Orion MLAS

- ↑ Jeff Foust. "Blue Origin proposes orbital vehicle". http://www.newspacejournal.com/2010/02/18/blue-origin-proposes-orbital-vehicle/.

- ↑ Frank Morring Jr.. "NASA Provides Seed Money For CCDev-2". http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_channel.jsp?channel=space&id=news/asd/2011/04/19/02.xml.

- ↑ Post, Hannah (6 May 2015). "Crew Dragon Completes Pad Abort Test". http://www.spacex.com/news/2015/05/06/crew-dragon-completes-pad-abort-test.

- ↑ "SpaceX moves launch of Dragon abort test to KSC". Local 6. http://www.clickorlando.com/news/spacex-moves-launch-of-dragon-abort-test-to-ksc/33950886.

- ↑ "Boeing's Starliner launch abort engine suffers problem during testing". 22 July 2018. https://spacenews.com/boeings-starliner-launch-abort-engine-suffers-problem-during-testing/.

- ↑ "Boeing's Starliner launch abort engine suffers problem during testing". 22 July 2018. https://spacenews.com/boeings-starliner-launch-abort-engine-suffers-problem-during-testing/.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen. "Boeing tests crew capsule escape system – Spaceflight Now" (in en-US). https://spaceflightnow.com/2019/11/04/boeing-starliner-pad-abort/.

- ↑ Stephen Clark. "Orbital sees bright future for Orion launch abort system". http://www.spaceflightnow.com/news/n1002/18orionlas/.

- ↑ "Kamanin Diaries". http://www.astronautix.com/articles/kamaries.htm.

- ↑ Davenport, Justin (12 September 2022). "New Shepard suffers in-flight abort on uncrewed NS-23 mission". https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2022/09/new-shepard-ns-23/.

External links

- Launch Pad Escape System Design (Human Spaceflight). NASA.gov

- Soyuz T-10-1

- NASA Orion Pad Abort 1 Test Flight Photos

- NASA Pad Abort 1 Flight Test Video Highlights

|